Safety Audits and Management Audits

During the 1990s, the organizational factors in safety policy are becoming increasingly important. At the same time, the views of organizations regarding safety have dramatically changed. Safety experts, most of whom have a technical training background, are thus confronted with a dual task. On the one hand, they have to learn to understand the organizational aspects and take them into account in constructing safety programmes. On the other hand, it is important that they be aware of the fact that the view of organizations is moving further and further away from the machine concept and placing a clear emphasis on less tangible and measurable factors such as organizational culture, behaviour modification, responsibility-raising or commitment. The first part of this article briefly covers developments in opinions relating to organizations, management, quality and safety. The second part of the article defines the implications of these developments for audit systems. This is then very briefly placed in a tangible context using the example of an actual safety audit system based on the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 9001 standards.

New Opinions Concerning Organization and Safety

Changes in social-economic circumstances

The economic crisis that started to impact upon the Western world in 1973 has had a significant influence on thought and action in the field of management, quality and work safety. In the past, the accent in economic development was placed on expansion of the market, increasing exports and improving productivity. However, the emphasis gradually shifted to the reduction of losses and the improvement of quality. In order to retain and acquire customers, a more direct response was provided to their requirements and expectations. This resulted in a need for greater product differentiation, with the direct consequence of greater flexibility within organizations in order to always be able to respond to market fluctuations on a “just in time” basis. Emphasis was placed on the commitment and creativity of employees as the major competitive advantage in the economic competitive struggle. Besides increasing quality, limiting loss-making activities became an important means of improving operating results.

Safety experts enlisted in this strategy by developing and instituting “total loss control” programmes. Not only are the direct costs of accidents or the increased insurance premiums significant in these programmes, but so also are all direct or indirect unnecessary costs and losses. A study of how much production should be increased in real terms to compensate for these losses immediately reveals that reducing costs is today often more efficient and profitable than increasing production.

In this context of improved productivity, reference was recently made to the major benefits of reducing absenteeism due to sickness and stimulating employee motivation. Against the background of these developments, safety policy is increasingly and clearly taking on a new form with different accents. In the past, most corporate leaders considered work safety as merely a legal obligation, as a burden they would quickly delegate to technical specialists. Today, safety policy is more and more distinctly being viewed as a way of achieving the two aims of reducing losses and optimizing corporate policy. Safety policy is therefore increasingly evolving into a reliable barometer of the soundness of the corporation’s success with respect to these aims. In order to measure progress, increased attention is being devoted to management and safety audits.

Organizational Theory

It is not only economic circumstances that have given company heads new insights. New visions relating to management, organizational theory, total quality care and, in the same vein, safety care, are resulting in significant changes. An important turning point in views on the organization was elaborated in the renowned work published by Peters and Waterman (1982), In Search of Excellence. This work was already espousing the ideas which Pascale and Athos (1980) discovered in Japan and described in The Art of Japanese Management. This new development can be symbolized in a sense by McKinsey’s “7-S” Framework (in Peters and Waterman 1982). In addition to three traditional management aspects (Strategy, Structure and Systems), corporations now also emphasize three additional aspects ( Staff, Skills and Style). All six of these interact to provide the input to the 7th “S”, Superordinate goals (figure 1). With this approach, a very clear accent is placed on the human-oriented aspects of the organization.

Figuer 1.The values, mission and organizational culture of a corporation according to McKinsey’s 7-S Framework

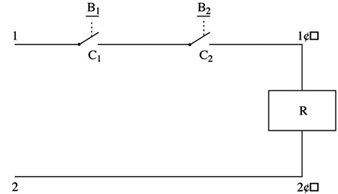

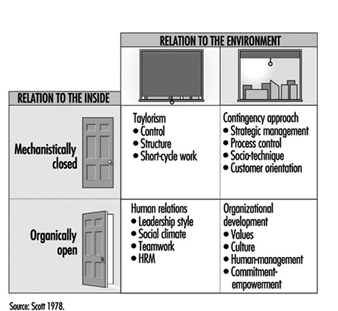

The fundamental shifts can best be demonstrated on the basis of the model presented by Scott (1978), which was also used by Peters and Waterman (1982). This model uses two approaches:

- The closed-system approaches deny the influence of developments from outside the organization. With the mechanistic closed approaches, the objectives of an organization are clearly defined and can be logically and rationally determined.

- Open-system approaches take outside influences fully into account, and the objectives are more the result of diverse processes, in which clearly irrational factors contribute to decision making. These organically open approaches more truly reflect the evolution of an organization, which is not determined mathematically or on the basis of deductive logic, but grows organically on the basis of real people and their interactions and values (figure 2).

Figure 2.Organizational Theories

Four fields are thus created in figure 2 . Two of these (Taylorism and contingency approach) are mechanically closed, and the other two (human relations and organizational development) are organically open. There has been enormous development in management theory, moving from the traditional rational and authoritarian machine model (Taylorism) to the human-oriented organic model of human resources management (HRM).

Organizational effectiveness and efficiency are being more clearly linked to optimal strategic management, a flat organizational structure and sound quality systems. Furthermore, attention is now given to superordinate goals and significant values that have a bonding effect within the organization, such as skills (on the basis of which the organization stands out from its competitors) and a staff that is motivated to maximum creativity and flexibility by placing the emphasis on commitment and empowerment. With these open approaches, a management audit cannot limit itself to a number of formal or structural characteristics of the organization. The audit must also include a search for methods to map out less tangible and measurable cultural aspects.

From product control to total quality management

In the 1950s, quality was limited to a post-factum end product control, total quality control (TQC). In the 1970s, partly stimulated by NATO and the automotive giant Ford, the accent shifted to the achievement of the goal of total quality assurance (TQA) during the production process. It was only during the 1980s that, stimulated by Japanese techniques, attention shifted towards the quality of the total management system and total quality management (TQM) was born. This fundamental change in the quality care system has taken place cumulatively in the sense that each foregoing stage was integrated into the next. It is also clear that while product control and safety inspection are facets more closely related to a Tayloristic organizational concept, quality assurance is more associated with a socio-technical system approach where the aim is not to betray the trust of the (external) customer. TQM, finally, relates to an HRM approach by the organization as it is no longer solely the improvement of the product that is involved, but continuous improvement of the organizational aspects in which explicit attention is also devoted to the employees.

In the total quality leadership (TQL) approach of the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), the emphasis is very strongly placed on the equal impact of the organization on the customer, the employees and the overall society, with the environment as the key point of attention. These objectives can be realized by including concepts such as “leadership” and “people management”.

It is clear that there is also a very important difference in emphasis between quality assurance as described in the ISO standards and the TQL approach of the EFQM. ISO quality assurance is an extended and improved form of quality inspection, focusing not only on the products and internal customers, but also on the efficiency of the technical processes. The objective of the inspection is to investigate the conformity with the procedures set out in ISO. TQM, on the other hand, endeavours to meet the expectations of all internal and external customers as well as all processes within the organization, including the more soft and human-oriented ones. The involvement, the commitment and the creativity of the employees are clearly important aspects of TQM.

From Human Error to Integrated Safety

Safety policy has evolved in a similar manner to quality care. Attention has shifted from post-factum accident analysis, with emphasis on the prevention of injuries, to a more global approach. Safety is seen more in the context of “total loss control” - a policy aimed at the avoidance of losses through management of safety involving the interaction of people, processes, materials, equipment, installations and the environment. Safety therefore focuses on the management of the processes that could lead to losses. In the initial development period of safety policy the emphasis was placed on a human error approach. Consequently, employees were given a heavy responsibility for the prevention of industrial accidents. Following a Tayloristic philosophy, conditions and procedures were drawn up and a control system was established to maintain the prescribed standards of behaviour. This philosophy may filter through into modern safety policy via the ISO 9000 concepts resulting in the imposition of a sort of implicit and indirect feeling of guilt upon the employees, with all the adverse consequences this entails for the corporate culture - for instance, a tendency may develop that performance will be impeded rather than enhanced.

At a later stage in the evolution of safety policy, it was recognized that employees carry out their work in a particular environment with well-defined working resources. Industrial accidents were considered as a multicausal event in a human/machine/environment system in which the emphasis shifted in a technical-system approach. Here again we find the analogy with quality assurance, where the accent is placed on controlling technical processes through means such as statistical process control.

Only recently, and partly stimulated by the TQM philosophy, has the emphasis in safety policy systems shifted into a social-system approach, which is a logical step in the improvement of the prevention system. In order to optimize the human/machine/environment system it is not sufficient to ensure safe machines and tools by means of a well-developed prevention policy, but there is also the need for a preventive maintenance system and the assurance of security among all technical processes. Moreover, it is of crucial importance that employees be sufficiently trained, skilled and motivated with regard to health and safety objectives. In today’s society, the latter objective can no longer be achieved through the authoritarian Tayloristic approach, as positive feedback is much more stimulating than a repressive control system that often has only negative effects. Modern management entails an open, motivating corporate culture, in which there is a common commitment to achieving key corporate objectives in a participatory, team-based approach. In the safety-culture approach, safety is an integral part of the objectives of the organizations and therefore an essential part of everyone’s task, starting with top management and passing along the entire hierarchical line down to employees on the shop floor.

Integrated safety

The concept of integrated safety immediately presents a number of central factors in an integrated safety system, the most important of which can be summarized as follows:

A clearly visible commitment from the top management. This commitment is not only given on paper, but is translated right down to the shop floor in practical achievements.

Active involvement of the hierarchical line and the central support departments. Care for safety, health and welfare is not only an integral part of everyone’s task in the production process, but is also integrated into the personnel policy, into preventive maintenance, into the design stage and into working with third parties.

Full participation of the employees. Employees are full discussion partners with whom open and constructive communication is possible, with their contribution being given full weight. Indeed, participation is of crucial importance for carrying through corporate and safety policy in an efficient and motivating way.

A suitable profile for a safety expert. The safety expert is no longer the technician or jack of all trades, but is a qualified adviser to the top management, with particular attention being devoted to optimizing the policy processes and the safety system. He or she is therefore not someone who is only technically trained, but also a person who, as a good organizer, can deal with people in an inspiring manner and collaborate in a synergetic way with other prevention experts.

A pro-active safety culture. The key aspect of an integrated safety policy is a pro-active safety culture, which includes, among other things, the following:

- Safety, health and welfare are the key ingredients of an organization’s value system and of the objectives it seeks to attain.

- An atmosphere of openness prevails, based on mutual trust and respect.

- There is a high level of cooperation with a smooth flow of information and an appropriate level of coordination.

- A pro-active policy is implemented with a dynamic system of constant improvement perfectly matching the prevention concept.

- The promotion of safety, health and welfare is a key component of all decision-making, consultations and teamwork.

- When industrial accidents occur, suitable preventive measures are sought, not a scapegoat.

- Members of staff are encouraged to act on their own initiative so that they possess the greatest possible authority, knowledge and experience, enabling them to intervene in an appropriate manner in unexpected situations.

- Processes are set in motion with a view to promoting individual and collective training to the maximum extent possible.

- Discussions concerning challenging and attainable health, safety and welfare objectives are held on a regular basis.

Safety and Management Audits

General description

Safety audits are a form of risk analysis and evaluation in which a systematic investigation is carried out in order to determine the extent to which the conditions are present that provide for the development and implementation of an effective and efficient safety policy. Each audit therefore simultaneously envisions the objectives that must be realized and the best organizational circumstances to put these into practice.

Each audit system should, in principle, determine the following:

- What is management seeking to achieve, by what means and by what strategy?

- What are the necessary provisions in terms of resources, structures, processes, standards and procedures that are required to achieve the proposed objectives, and what has been provided? What minimum programme can be put forward?

- What are the operational and measurable criteria that must be met by the chosen items to allow the system to function optimally?

The information is then thoroughly analysed to examine to what extent the current situation and the degree of achievement meet the desired criteria, followed by a report with positive feedback that emphasizes the strong points, and corrective feedback that refers to aspects requiring further improvement.

Auditing and strategies for change

Each audit system explicitly or implicitly contains a vision both of an ideal organization’s design and conceptualization, and of the best way of implementing improvements.

Bennis, Benne and Chin (1985) distinguish three strategies for planned changes, each based on a different vision of people and of the means of influencing behaviour:

- Power-force strategies are based on the idea that the behaviour of employees can be changed by exercising sanctions.

- Rational-empirical strategies are based on the axiom that people make rational choices depending on maximizing their own benefits.

- Normative-re-educative strategies are based on the premise that people are irrational, emotional beings and in order to realize a real change, attention must also be devoted to their perception of values, culture, attitudes and social skills.

Which influencing strategy is most appropriate in a specific situation not only depends on the starting vision, but also on the actual situation and the existing organizational culture. In this respect it is very important to know which sort of behaviour to influence. The famous model devised by Danish risk specialist Rasmussen (1988) distinguishes among the following three sorts of behaviour:

- Routine actions (skill-based behaviour) automatically follow the associated signal. Such actions are carried out without one’s consciously devoting attention to them - for example, touch-typing or manually changing gears when driving.

- Actions in accordance with instructions (rule-based) require more conscious attention because no automatic response to the signal is present and a choice must be made between different possible instructions and rules. These are often actions which can be placed in an “ifthen” sequence, as in “If the meter rises to 50 then this valve must be closed”.

- Actions based on knowledge and insight (knowledge-based) are carried out after a conscious interpretation and evaluation of the different problem signals and the possible alternative solutions. These actions therefore presuppose a fairly high degree of knowledge of and insight into the process concerned, and the ability to interpret unusual signals.

Strata in behavioural and cultural change

Based on the above, most audit systems (including those based on the ISO series of standards) implicitly depart from power-force strategies or rational-empirical strategies, with their emphasis on routine or procedural behaviour. This means that insufficient attention is paid in these audit systems to “knowledge-based behaviour” that can be influenced mainly via normative–re-educative strategies. In the typology used by Schein (1989), attention is devoted only to the tangible and conscious surface phenomena of the organizational culture and not to the deeper invisible and subconscious strata that refer more to values and fundamental presuppositions.

Many audit systems limit themselves to the question of whether a particular provision or procedure is present. It is therefore implicitly assumed that the sheer existence of this provision or procedure is a sufficient guarantee for the good functioning of the system. Besides the existence of certain measures, there are always different other “strata” (or levels of probable response) that must be addressed in an audit system to provide sufficient information and guarantees for the optimum functioning of the system.

In more concrete terms, the following example concerns response to a fire emergency:

- A given provision, instruction or procedure is present (“sound the alarm and use the extinguisher”).

- A given instruction or procedure is also familiarly known to the parties concerned (workers know where alarms and extinguishers are located and how to activate and use them).

- The parties concerned also know as much as possible as to the “why and wherefore” of a particular measure (employees have been trained or educated in extinguisher use and typical types of fires).

- The employee is also motivated to apply needful measures (self preservation, save the job, etc.).

- There is sufficient motivation, competence and ability to act in unforeseen circumstances (employees know what to do in the event fire gets out of hand, requiring professional fire-fighting response).

- There are good human relations and an atmosphere of open communication (supervisors, managers and employees have discussed and agreed upon fire emergency response procedures).

- Spontaneous creative processes originate in a learning organiz-ation (changes in procedures are implemented following “lessons learned” in actual fire situations).

Table 1 lays out some strata in quality audio safety policy.

Table 1. Strata in quality and safety policy

|

Strategies |

Behaviour |

||

|

Skills |

Rules |

Knowledge |

|

|

Power-force |

Human error approach |

||

|

Rational-empirical |

Technical system approach |

||

|

Normative-re-educative |

Social system approach TQM |

Safety culture approach PAS EFQM |

|

The Pellenberg Audit System

The name Pellenberg Audit System (PAS) derives from the place where the designers gathered many times to develop the system (the Maurissens Château in Pellenberg, a building of the Catholic University of Leuven). PAS is the result of intense collaboration by an interdisciplinary team of experts with years of practical experience, both in the area of quality management and in the area of safety and environmental problems, in which a variety of approaches and experiences were brought together. The team also received support from the university science and research departments, and thus benefited from the most recent insights in the fields of management and organizational culture.

PAS encompasses an entire set of criteria that a superior company prevention system ought to meet (see table 2). These criteria are classified in accordance with the ISO standard system (quality assurance in design, development, production, installation and servicing). However, PAS is not a simple translation of the ISO system into safety, health and welfare. A new philosophy is developed, departing from the specific product that is achieved in safety policy: meaningful and safe jobs. The contract of the ISO system is replaced by the provisions of the law and by the evolving expectations that exist among the parties involved in the social field with regard to health, safety and welfare. The creation of safe and meaningful jobs is seen as an essential objective of each organization within the framework of its social responsibility. The enterprise is the supplier and the customers are the employees.

Table 2. PAS safety audit elements

|

PAS safety audit elements |

Correspondence with ISO 9001 |

|

|

1. |

Management responsibility |

|

|

1.1. |

Safety policy |

4.1.1. |

|

1.2. |

Organization |

|

|

1.2.1. |

Responsibility and authority |

4.1.2.1. |

|

1.2.2. |

Verification resources and personnel |

4.1.2.2. |

|

1.2.3. |

Health and safety service |

4.1.2.3. |

|

1.3. |

Safety management system review |

4.1.3. |

|

2. |

Safety management system |

4.2. |

|

3. |

Obligations |

4.3. |

|

4. |

Design control |

|

|

4.1. |

General |

4.4.1. |

|

4.2. |

Design and development planning |

4.4.2. |

|

4.3. |

Design input |

4.4.3. |

|

4.4. |

Design output |

4.4.4. |

|

4.5. |

Design verification |

4.4.5. |

|

4.6. |

Design changes |

4.4.6. |

|

5. |

Document control |

|

|

5.1. |

Document approval and issue |

4.5.1. |

|

5.2. |

Document changes/modifications |

4.5.2. |

|

6. |

Purchasing and contracting |

|

|

6.1. |

General |

4.6.1. |

|

6.2. |

Assessment of suppliers and contractors |

4.6.2. |

|

6.3. |

Purchasing data |

4.6.3. |

|

6.4. |

Third party’s products |

4.7. |

|

7. |

Identification |

4.8. |

|

8. |

Process control |

|

|

8.1. |

General |

4.9.1. |

|

8.2. |

Process safety control |

4.11. |

|

9. |

Inspection |

|

|

9.1. |

Receiving and pre-start-up inspection |

4.10.1. |

|

9.2. |

Periodic inspections |

4.10.2. |

|

9.3. |

Inspection records |

4.10.4. |

|

9.4. |

Inspection equipment |

4.11. |

|

9.5. |

Inspection status |

4.12. |

|

10. |

Accidents and incidents |

4.13. |

|

11. |

Corrective and preventive action |

4.13. |

|

12. |

Safety records |

4.16. |

|

13. |

Internal safety audits |

4.17. |

|

14. |

Training |

4.18. |

|

15. |

Maintenance |

4.19. |

|

16. |

Statistical techniques |

4.20. |

Several other systems are integrated in the PAS system:

- At a strategic level, the insights and requirements of ISO are of particular importance. As far as possible, these are comple-mented by the management vision as this was originally devel-oped by the European Foundation for Quality Management.

- At a tactical level, the systematics of the “Management’s Oversight and Risk Tree” encourages people to seek out what are the necessary and sufficient conditions in order to achieve the desired safety result.

- At an operational level a multitude of sources could be drawn upon, including existing legislation, regulations and other criteria such as the International Safety Rating System (ISRS), in which the emphasis is placed on certain concrete conditions that should guarantee the safety result.

The PAS constantly refers to the broader corporate policy within which the safety policy is embedded. After all, an optimum safety policy is at the same time a product and a producer of a pro-active company policy. Assuming that a safe company is at the same time an effective and efficient organization and vice versa, special attention is therefore devoted to the integration of safety policy in the overall policy. Essential ingredients of a future-oriented corporate policy include a strong corporate culture, a far-reaching commitment, the participation of the employees, a special emphasis on the quality of the work, and a dynamic system of continual improvement. Although these insights also partly form the background of the PAS, they are not always very easy to reconcile with the more formal and procedural approach of the ISO philosophy.

Formal procedures and directly identifiable results are indisputably important in safety policy. However, it is not enough to base the safety system on this approach alone. The future results of a safety policy are dependent on the present policy, on the systematic efforts, on the constant search for improvements, and particularly on the fundamental optimizing of processes that ensure durable results. This vision is incorporated in the PAS system, with strong emphasis among other things on a systematic improvement of the safety culture.

One of the main advantages of the PAS is the opportunity for synergy. By departing from the systematics of ISO, the diverse lines of approach become immediately recognizable for all those concerned with total quality management. There are clearly several opportunities for synergy between these various policy areas because in all these fields the improvement of the management processes is the key aspect. A careful purchasing policy, a sound system of preventive maintenance, good housekeeping, participatory management and the stimulation of an enterprising approach by employees are of paramount importance for all these policy areas.

The various care systems are organized in an analogous manner, based on principles such as the commitment of top management, the involvement of the hierarchical line, the active participation of employees, and a valorized contribution from the specific experts. The different systems also contain analogous policy instruments such as the policy statement, annual action plans, measuring and control systems, internal and external audits and so on. The PAS system therefore clearly invites the pursuance of an effective, cost-saving, synergetic cooperation between all these care systems.

The PAS does not offer the easiest road to achievement in the short term. Few company managers allow themselves to be seduced by a system that promises great benefits in the short term with little effort. Every sound policy requires an in-depth approach, with strong foundations being laid for future policy. More important than results in the short term is the guarantee that a system is being built up that will generate sustainable results in the future, not only in the field of safety, but also at the level of a generally effective and efficient corporate policy. In this respect working towards health, safety and welfare also means working towards safe and meaningful jobs, motivated employees, satisfied customers and an optimum operating result. All this takes place in a dynamic, pro-active atmosphere.

Summary

Continual improvement is an essential precondition for each safety audit system that seeks to reap lasting success in today’s rapidly evolving society. The best guarantee for a dynamic system of continual improvement and constant flexibility is the full commitment of competent employees who grow with the overall organization because their efforts are systematically valorized and because they are given the opportunities to develop and regularly update their skills. Within the safety audit process, the best guarantee of lasting results is the development of a learning organization in which both the employees and the organization continue to learn and evolve.

Work-Related Accident Costs

Workers who are the victims of work-related accidents suffer from material consequences, which include expenses and loss of earnings, and from intangible consequences, including pain and suffering, both of which may be of short or long duration. These consequences include:

- doctor’s fees, cost of ambulance or other transport, hospital charges or fees for home nursing, payments made to persons who gave assistance, cost of artificial limbs and so on

- the immediate loss of earnings during absence from work (unless insured or compensated)

- loss of future earnings if the injury is permanently disabling, long term or precludes the victim’s normal advancement in his or her career or occupation

- permanent afflictions resulting from the accident, such as mutilation, lameness, loss of vision, ugly scars or disfigurement, mental changes and so on, which may reduce life expectancy and give rise to physical or psychological suffering, or to further expenses arising from the victim’s need to find a new occupation or interests

- subsequent economic difficulties with the family budget if other members of the family have to either go to work to replace lost income or give up their employment in order to look after the victim. There may also be additional loss of income if the victim was engaged in private work outside normal working hours and is no longer able to perform it.

- anxiety for the rest of the family and detriment to their future, especially in the case of children.

Workers who become victims of accidents frequently receive compensation or allowances both in cash and in kind. Although these do not affect the intangible consequences of the accident (except in exceptional circumstances), they constitute a more or less important part of the material consequences, inasmuch as they affect the income which will take the place of the salary. There is no doubt that part of the overall costs of an accident must, except in very favourable circumstances, be borne directly by the victims.

Considering the national economy as a whole, it must be admitted that the interdependence of all its members is such that the consequences of an accident affecting one individual will have an adverse effect on the general standard of living, and may include the following:

- an increase in the price of manufactured products, since the direct and indirect expenses and losses resulting from an accident may result in an increase in the cost of making the product

- a decrease in the gross national product as a result of the adverse effects of accidents on people, equipment, facilities and materials; these effects will vary according to the availability in each country of workers, capital and material resources

- additional expenses incurred to cover the cost of compensating accident victims and pay increased insurance premiums, and the amount necessary to provide safety measures required to prevent similar occurrences.

One of the functions of society is that it must protect the health and income of its members. It meets these obligations through the creation of social security institutions, health programmes (some governments provide free or low-cost medical care to their constituents), injury compensation insurance and safety systems (including legislation, inspection, assistance, research and so on), the administrative costs of which are a charge on society.

The level of compensation benefits and the amount of resources devoted to accident prevention by governments are limited for two reasons: because they depend (1) on the value placed on human life and suffering, which varies from one country to another and from one era to another; and (2) on the funds available and the priorities allocated for other services provided for the protection of the public.

As a result of all this, a considerable amount of capital is no longer available for productive investment. Nevertheless, the money devoted to preventive action does provide considerable economic benefits, to the extent that there is a reduction in the total number of accidents and their cost. Much of the effort devoted to the prevention of accidents, such as the incorporation of higher safety standards into machinery and equipment and the general education of the population before working age, are equally useful both inside and outside the workplace. This is of increasing importance because the number and cost of accidents occurring at home, on the road and in other non-work-related activities of modern life continues to grow. The total cost of accidents may be said to be the sum of the cost of prevention and the cost of the resultant changes. It would not seem unreasonable to recognize that the cost to society of the changes which could result from the implementation of a preventive measure may exceed the actual cost of the measure many times over. The necessary financial resources are drawn from the economically active section of the population, such as workers, employers and other taxpayers through systems which work either on the basis of contributions to the institutions that provide the benefits, or through taxes collected by the state and other public authorities, or by both systems. At the level of the undertaking the cost of accidents includes expenses and losses, which are made up of the following:

- expenses incurred while setting up the system of work and the related equipment and machinery with a view to ensuring safety in the production process. Estimation of these expenses is difficult because it is not possible to draw a line between the safety of the process itself and that of the workers. Major sums are involved which are entirely expended before production commences and are included in general or special costs to be amortized over a period of years.

- expenses incurred during production, which in turn include: (1) fixed charges related to accident prevention, notably for medical, safety and educational services and for arrangements for the workers’ participation in the safety programme; (2) fixed charges for accident insurance, plus variable charges in schemes where premiums are based on the number of accidents; (3) varying charges for activities related to accident prevention (these depend largely on accident frequency and severity, and include the cost of training and information activities, safety campaigns, safety programmes and research, and workers’ participation in these activities); (4) costs arising from personal injuries (These include the cost of medical care, transport, grants to accident victims and their families, administrative and legal consequences of accidents, salaries paid to injured persons during their absence from work and to other workers during interruptions to work after an accident and during subsequent inquiries and investigations, and so on.); (5) costs arising from material damage and loss which need not be accompanied by personal injury. In fact, the most typical and expensive material damage in certain branches of industry arises in circumstances other than those which result in personal injury; attention should be concentrated upon the few points in common between the techniques of material damage control and those required for the prevention of personal injury.

- losses arising out of a fall in production or from the costs of introducing special counter-measures, both of which may be very expensive.

In addition to affecting the place where the accident occurred, successive losses may occur at other points in the plant or in associated plants; apart from economic losses which result from work stoppages due to accidents or injuries, account must be taken of the losses resulting when the workers stop work or come out on strike during industrial disputes concerning serious, collective or repeated accidents.

The total value of these costs and losses are by no means the same for every undertaking. The most obvious differences depend on the particular hazards associated with each branch of industry or type of occupation and on the extent to which appropriate safety precautions are applied. Rather than trying to place a value on the initial costs incurred while incorporating accident prevention measures into the system at the earliest stages, many authors have tried to work out the consequential costs. Among these may be cited: Heinrich, who proposed that costs be divided into “direct costs” (particularly insurance) and “indirect costs” (expenses incurred by the manufacturer); Simonds, who proposed dividing the costs into insured costs and non-insured costs; Wallach, who proposed a division under the different headings used for analysing production costs, viz. labour, machinery, maintenance and time expenses; and Compes, who defined the costs as either general costs or individual costs. In all of these examples (with the exception of Wallach), two groups of costs are described which, although differently defined, have many points in common.

In view of the difficulty of estimating overall costs, attempts have been made to arrive at a suitable value for this figure by expressing the indirect cost (uninsured or individual costs) as a multiple of the direct cost (insured or general costs). Heinrich was the first to attempt to obtain a value for this figure and proposed that the indirect costs amounted to four times the direct costs—that is, that the total cost amounts to five times the direct cost. This estimation is valid for the group of undertakings studied by Heinrich, but is not valid for other groups and is even less valid when applied to individual factories. In a number of industries in various industrialized countries this value has been found to be of the order of 1 to 7 (4 ± 75%) but individual studies have shown that this figure can be considerably higher (up to 20 times) and may even vary over a period of time for the same undertaking.

There is no doubt that money spent incorporating accident prevention measures into the system during the initial stages of a manufacturing project will be offset by the reduction of losses and expenses that would otherwise have been incurred. This saving is not, however, subject to any particular law or fixed proportion, and will vary from case to case. It may be found that a small expenditure results in very substantial savings, whereas in another case a much greater expenditure results in very little apparent gain. In making calculations of this kind, allowance should always be made for the time factor, which works in two ways: current expenses may be reduced by amortizing the initial cost over several years, and the probability of an accident occurring, however rare it may be, will increase with the passage of time.

In any given industry, where permitted by societal factors, there may be no financial incentive to reduce accidents in view of the fact that their cost is added to the production cost and is thus passed on to the consumer. This is a different matter, however, when considered from the point of view of an individual undertaking. There may be a great incentive for an undertaking to take steps to avoid the serious economic effects of accidents involving key personnel or essential equipment. This is particularly so in the case of small plants which do not have a reserve of qualified staff, or those engaged in certain specialized activities, as well as in large, complex facilities, such as in the process industry, where the costs of replacement could surpass the capacity to raise capital. There may also be cases where a larger undertaking can be more competitive and thus increase its profits by taking steps to reduce accidents. Furthermore, no undertaking can afford to overlook the financial advantages that stem from maintaining good relations with workers and their trade unions.

As a final point, when passing from the abstract concept of an undertaking to the concrete reality of those who occupy senior positions in the business (i.e., the employer or the senior management), there is a personal incentive which is not only financial and which stems from the desire or the need to further their own career and to avoid the penalties, legal and otherwise, which may befall them in the case of certain types of accident. The cost of occupational accidents, therefore, has repercussions on both the national economy and that of each individual member of the population: there is thus an overall and an individual incentive for everybody to play a part in reducing this cost.

Principles of Prevention: Safety Information

Sources of Safety Information

Manufacturers and employers throughout the world provide a vast amount of safety information to workers, both to encourage safe behaviour and to discourage unsafe behaviour. These sources of safety information include, among others, regulations, codes and standards, industry practices, training courses, Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDSs), written procedures, safety signs, product labels and instruction manuals. Information provided by each of these sources varies in its behavioural objectives, intended audience, content, level of detail, format and mode of presentation. Each source may also design its information so as to be relevant to the different stages of task performance within a potential accident sequence.

Four Stages of the Accident Sequence

The behavioural objectives of particular sources of safety information correspond or “map” naturally to the four different stages of the accident sequence (table 1).

Table 1. Objectives and example sources of safety information mapped to the accident sequence

|

Task stage in accident sequence |

||||

|

Prior to task |

Routine task performance |

Abnormal task conditions |

Accident conditions |

|

|

Objectives |

Educate and persuade worker of the nature and level of risk, precautions, remedial measures and emergency procedures. |

Instruct or remind worker to follow safe procedures or take precautions. |

Alert worker of abnormal conditions. Specify needed actions. |

Indicate locations of safety and first aid equipment, exits and emergency procedures. Specify remedial and emergency procedures. |

|

Example |

Training manuals, videos or programmes, hazard communication programmes, material safety data sheets, safety propaganda, safety feedback |

Instruction manuals, job performance aids, checklists, written procedures, warning signs and labels |

Warning signals: visual, auditory, or olfactory. Temporary tags, signs, barriers or lock-outs |

Safety information signs, labels, and markings, material safety data sheets |

First stage. At the first stage in the accident sequence, sources of information provided prior to the task, such as safety training materials, hazard communication programmes and various forms of safety programme materials (including safety posters and campaigns) are used to educate workers about risks and persuade them to behave safely. Methods of education and persuasion (behaviour modification) attempt not only to reduce errors by improving worker knowledge and skills but also to reduce intentional violations of safety rules by changing unsafe attitudes. Inexperienced workers are often the target audience at this stage, and therefore the safety information is much more detailed in content than at the other stages. It must be emphasized that a well-trained and motivated workforce is a prerequisite for safety information to be effective at the three following stages of the accident sequence.

Second stage. At the second stage in the accident sequence, sources such as written procedures, checklists, instructions, warning signs and product labels can provide critical safety information during routine task performance. This information usually consists of brief statements which either instruct less skilled workers or remind skilled workers to take necessary precautions. Following this approach can help prevent workers from omitting either precautions or other critical steps in a task. Statements providing such information are often embedded at the appropriate stage within step-by-step instructions describing how to perform a task. Warning signs at appropriate locations can play a similar role: for example, a warning sign located at the entrance to a workplace might state that safety hard hats must be worn inside.

Third stage. At the third stage in the accident sequence, highly conspicuous and easily perceived sources of safety information alert workers of abnormal or unusually hazardous conditions. Examples include warning signals, safety markings, tags, signs, barriers or lock-outs. Warning signals can be visual (flashing lights, movements, etc.), auditory (buzzers, horns, tones, etc.), olfactory (odours), tactile (vibrations) or kinaesthetic. Certain warning signals are inherent to products when they are in hazardous states (e.g., the odour released upon opening a container of acetone). Others are designed into machinery or work environments (e.g., the back-up signal on a fork-lift truck). Safety markings refer to methods of non-verbally identifying or highlighting potentially hazardous elements of the environment (e.g., by painting step edges yellow or emergency stops red). Safety tags, barriers, signs or lock-outs are placed at points of hazard and are often used to prevent workers from entering areas or activating equipment during maintenance, repair or other abnormal conditions.

Fourth stage. At the fourth stage in the accident sequence, the focus is on expediting worker performance of emergency procedures at the time an accident is occurring, or on the performance of remedial measures shortly after the accident. Safety information signs and markings conspicuously indicate facts critical to adequate performance of emergency procedures (e.g., the locations of exits, fire extinguishers, first aid stations, emergency showers, eyewash stations or emergency releases). Product safety labels and MSDSs may specify remedial and emergency procedures to be followed.

However, if safety information is to be effective at any stage in the accident sequence, it must first be noticed and understood, and if the information has been previously learned, it must also be remembered. Then the worker must both decide to comply with the provided message and be physically able to do so. Successfully attaining each of these steps for effectiveness can be difficult; however, guidelines describing how to design safety information are of some assistance.

Design Guidelines and Requirements

Standards-making organizations, regulatory agencies and the courts through their decisions have traditionally both instituted guidelines and imposed requirements regarding when and how safety information is to be provided. More recently, there has been a trend towards developing guidelines based on scientific research concerning the factors which influence the effectiveness of safety information.

Legal requirements

In most industrialized countries, government regulations require that certain forms of safety information be provided to workers. For example, in the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed several labelling requirements for toxic chemicals. The Department of Transportation (DOT) makes specific provisions regarding the labelling of hazardous materials in transport. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has promulgated a hazard communication standard that applies to workplaces where toxic or hazardous materials are in use, which requires training, container labelling, MSDSs and other forms of warnings.

In the United States, the failure to warn also can be grounds for litigation holding manufacturers, employers and others liable for injuries incurred by workers. In establishing liability, the Theory of Negligence takes into consideration whether the failure to provide adequate warning is judged to be unreasonable conduct based on (1) the foreseeability of the danger by the manufacturer, (2) the reasonableness of the assumption that a user would realize the danger and (3) the degree of care that the manufacturer took to inform the user of the danger. The Theory of Strict Liability requires only that the failure to warn caused the injury or loss.

Voluntary standards

A large set of existing standards provide voluntary recommendations regarding the use and design of safety information. These standards have been developed by multilateral groups and agencies, such as the United Nations, the European Economic Community (EEC’s EURONORM), the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC); and by national groups, such as the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), the British Standards Institute, the Canadian Standards Association, the German Institute for Normalization (DIN) and the Japanese Industrial Standards Committee.

Among consensus standards, those developed by ANSI in the United States are of special significance. Since the mid-1980s, five new ANSI standards focusing on safety signs and labels have been developed and one significant standard has been revised. The new standards are: (1) ANSI Z535.1, Safety Color Code, (2) ANSI Z535.2, Environmental and Facility Safety Signs, (3) ANSI Z535.3, Criteria for Safety Symbols, (4) ANSI Z535.4, Product Safety Signs and Labels, and (5) ANSI Z535.5, Accident Prevention Tags. The recently revised standard is ANSI Z129.1–1988, Hazardous Industrial Chemicals—Precautionary Labeling. Furthermore, ANSI has published the Guide for Developing Product Information.

Design specifications

Design specifications can be found in consensus and governmental safety standards specifying how to design the following:

- Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDSs). The OSHA hazard communication standard specifies that employers must have a MSDS in the workplace for each hazardous chemical used. The standard requires that each sheet be written in English, list its date of preparation and provide the scientific and common names of the hazardous chemical mentioned. It also requires the MSDS to describe (1) physical and chemical characteristics of the hazardous chemical, (2) physical hazards, including potential for fire, explosion and reactivity, (3) health hazards, including signs and symptoms of exposure, and health conditions potentially aggravated by the chemical, (4) the primary route of entry, (5) the OSHA permissible exposure limit, the ACGIH threshold limit value or other recommended limits, (6) carcinogenic properties, (7) generally applicable precautions, (8) generally applicable control measures, (9) emergency and first aid procedures and (10) the name, address and telephone number of a party able to provide, if necessary, additional information on the hazardous chemical and emergency procedures.

- Instructional labels and manuals. Few consensus standards currently specify how to design instructional labels and manuals. This situation is, however, quickly changing. The ANSI Guide for Developing User Product Information was published in 1990, and several other consensus organizations are working on draft documents. Without an overly scientific foundation, the ANSI Consumer Interest Council, which is responsible for the above guidelines, has provided a reasonable outline to manufacturers regarding what to consider in producing instruction/operator manuals. They have included sections entitled: “Organizational Elements”, “Illustrations”, “Instructions”, “Warnings”, “Standards”, “How to Use Language”, and “An Instructions Development Checklist”. While the guideline is brief, the document represents a useful initial effort in this area.

- Safety symbols. Numerous standards throughout the world contain provisions regarding safety symbols. Among such standards, the ANSI Z535.3 standard, Criteria for Safety Symbols, is particularly relevant for industrial users. The standard presents a significant set of selected symbols shown in previous studies to be well understood by workers in the United States. Perhaps more importantly, the standard also specifies methods for designing and evaluating safety symbols. Important provisions include the requirement that (1) new symbols must be correctly identified during testing by at least 85% of 50 or more representative subjects, (2) symbols which don’t meet the above criteria should be used only when equivalent printed verbal messages are also provided and (3) employers and product manufacturers should train workers and users regarding the intended meaning of the symbols. The standard also makes new symbols developed under these guidelines eligible to be considered for inclusion in future revisions of the standard.

- Warning signs, labels and tags. ANSI and other standards provide very specific recommendations regarding the design of warning signs, labels and tags. These include, among other factors, particular signal words and text, colour coding schemes, typography, symbols, arrangement and hazard identification (table 2 ). Among the most popular signal words recommended are: DANGER, to indicate the highest level of hazard; WARNING, to represent an intermediate hazard; and CAUTION, to indicate the lowest level of hazard. Colour coding methods are to be used to consistently associate colours with particular levels of hazard. For example, red is used in all of the standards in table 2 to represent DANGER, the highest level of hazard. Explicit recommendations regarding typography are given in nearly all the systems. The most general commonality between the systems is the recommended use of sans-serif typefaces. Varied recommendations are given regarding the use of symbols and pictographs. The FMC and the Westinghouse systems advocate the use of symbols to define the hazard and to convey the level of hazard (FMC 1985; Westinghouse 1981). Other standards recommend symbols only as a supplement to words. Another area of substantial variation, shown in table 1 , pertains to the recommended label arrangements. The proposed arrangements generally include elements discussed above and specify the image (graphic content or colour), the background (shape, colour); the enclosure (shape, colour) and the surround (shape, colour). Many of the systems also precisely describe the arrangement of the written text and provide guidance regarding methods of hazard identification.

Table 2. Summary of recommendations within selected warning systems

|

System |

Signal words |

Colour coding |

Typography |

Symbols |

Arrangement |

|

ANSI Z129.1 |

Danger |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Skull-and-crossbones as supplement to words. |

Label arrangement not specified; examples given |

|

ANSI Z535.2 |

Danger |

Red |

Sans serif, upper case, |

Symbols and pictographs |

Defines signal word, word message, symbol panels in 1 to 3 panel designs. 4 shapes for special use. Can use ANSI Z535.4 for uniformity. |

|

ANSI Z535.4 |

Danger |

Red |

Sans serif, upper case, |

Symbols and pictographs |

Defines signal word, message, pictorial panels in order of general to specific. Can use ANSI Z535.2 for uniformity. Use ANSI Z129.1 for chemical hazards. |

|

NEMA Guidelines: |

Danger |

Red |

Not specified |

Electric shock symbol |

Defines signal word, hazard, consequences, instructions, symbol. Does not specify order. |

|

SAE J115 Safety Signs |

Danger |

Red |

Sans serif typeface, upper |

Layout to accommodate |

Defines 3 areas: signal word panel, pictorial panel, message panel. Arrange in order of general to specific. |

|

ISO Standard: ISO |

None. 3 kinds of labels: |

Red |

Message panel is added |

Symbols and pictographs |

Pictograph or symbol is placed inside appropriate shape with message panel below if necessary |

|

OSHA 1910.145 Specification for Accident Prevention |

Danger |

Red |

Readable at 5 feet or as |

Biological hazard symbol. Major message can be supplied by pictograph |

Signal word and major message (tags only) |

|

OSHA 1910.1200 |

Per applicable |

In English |

Only as Material Safety Data Sheet |

||

|

Westinghouse |

Danger |

Red |

Helvetica bold and regular |

Symbols and pictographs |

Recommends 5 components: signal word, symbol/pictograph, hazard, result of ignoring warning, avoiding hazard |

Source: Adapted from Lehto and Miller 1986; Lehto and Clark 1990.

Certain standards may also specify the content and wording of warning signs or labels in some detail. For example, ANSI Z129.1 specifies that chemical warning labels must include (1) identification of the chemical product or its hazardous component(s), (2) a signal word, (3) a statement of hazard(s), (4) precautionary measures, (5) instructions in case of contact or exposure, (6) antidotes, (7) notes to physicians, (8) instructions in case of fire and spill or leak and (9) instructions for container handling and storage. This standard also specifies a general format for chemical labels that incorporate these items. The standard also provides extensive and specific recommended wordings for particular messages.

Cognitive guidelines

Design specifications, such as those discussed above, can be useful to developers of safety information. However, many products and situations are not directly addressed by standards or regulations. Certain design specifications may not be scientifically proven, and, in extreme cases, conforming with standards and regulations may actually reduce the effectiveness of safety information. To ensure effectiveness, developers of safety information consequently may need to go beyond safety standards. Recognizing this issue, the International Ergonomics Association (IEA) and International Foundation for Industrial Ergonomics and Safety Research (IFIESR) recently supported an effort to develop guidelines for warning signs and labels (Lehto 1992) which reflect published and unpublished studies on effectiveness and have implications regarding the design of nearly all forms of safety information. Six of these guidelines, presented in slightly modified form, are as follows.

- Match sources of safety information to the level of performance at which critical errors occur for a given population. In specifying what and how safety information is to be provided, this guideline emphasizes the need to focus attention on (1) critical errors that can cause significant damage and (2) the level of worker performance at the time the error is made. This objective often can be attained if sources of safety information are matched to behavioural objectives consistently with the mapping shown in table 1 and discussed earlier.

- Integrate safety information into the task and hazard-related context. Safety information should be provided in a way that makes it likely to be noticed at the time it is most relevant, which almost always is the moment when action needs to be taken. Recent research has confirmed that this principle is true for both the placement of safety messages within instructions and the placement of safety information sources (such as warning signs) in the physical environment. One study showed that people were much more likely to notice and comply with safety precautions when they were included as a step within instructions, rather than separated from instructional text as a separate warning section. It is interesting to observe that many safety standards conversely recommend or require that precautionary and warning information be placed in a separate section.

- Be selective. Providing excessive amounts of safety information increases the time and effort required to find what is relevant to the emergent need. Sources of safety information should consequently focus on providing relevant information which does not exceed what is needed for the immediate purpose. Training programmes should provide the most detailed information. Instruction manuals, MSDSs and other reference sources should be more detailed than warning signs, labels or signals.

- Keep the cost of compliance within a reasonable level. A substantial number of studies have indicated that people become less likely to follow safety precautions when doing so is perceived to involve a significant “cost of compliance”. Safety information should therefore be provided in a way that minimizes the difficulty of complying with its message. Occasionally this goal can be attained by providing the information at a time and location when complying is convenient.

- Make symbols and text as concrete as possible. Research has shown that people are better able to understand concrete, rather than abstract, words and symbols used within safety information. Skill and experience, however, play a major role in determining the value of concreteness. It is not unusual for highly skilled workers to both prefer and better understand abstract terminology.

- Simplify the syntax and grammar of text and combinations of symbols. Writing text that poor readers, or even adequate readers, can comprehend is not an easy task. Numerous guidelines have been developed in attempts to alleviate such problems. Some basic principles are (1) use words and symbols understood by the target audience, (2) use consistent terminology, (3) use short, simple sentences constructed in the standard subject-verb-object form, (4) avoid negations and complex conditional sentences, (5) use the active rather than passive voice, (6) avoid using complex pictographs to describe actions and (7) avoid combining multiple meanings in a single figure.

Satisfying these guidelines requires consideration of a substantial number of detailed issues as addressed in the next section.

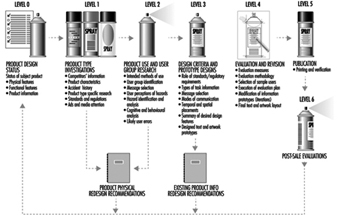

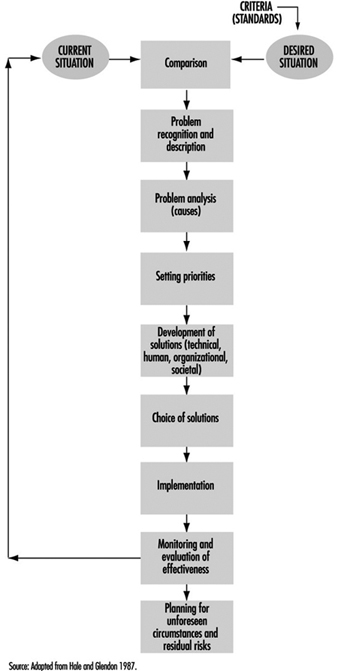

Developing Safety Information

The development of safety information meant to accompany products, such as safety warnings, labels and instructions, often requires extensive investigations and development activities involving considerable resources and time. Ideally, such activities (1) coordinate the development of product information with design of the product itself, (2) analyse product features which affect user expectations and behaviours, (3) identify the hazards associated with use and likely misuse of the product, (4) research user perceptions and expectations regarding product function and hazard characteristics and (5) evaluate product information using methods and criteria consistent with the goals of each component of product information. Activities accomplishing these objectives can be grouped into several levels. While in-house product designers are able to accomplish many of the tasks designated, some of these tasks involve the application of methodologies most familiar to professionals with backgrounds in human factors engineering, safety engineering, document design and the communication sciences. Tasks falling within these levels are summarized as follows and are shown in figure 1 :

Figure 1.A model for designing and evaluating product information

Level 0: Product design status

Level 0 is both the starting point for initiating a product information project, and the point at which feedback regarding design alternatives will be received and new iterations at the basic model level will be forwarded. At the initiation of a product information project, the researcher begins with a particular design. The design can be in the concept or prototype stage or as currently being sold and used. A major reason for designating a Level 0 is the recognition that the development of product information must be managed. Such projects require formal budgets, resources, planning, and accountability. The largest benefits to be gained from a systematic product information design are achieved when the product is in the pre-production concept or prototype state. However, applying the methodology to existing products and product information is quite appropriate and extremely valuable.

Level 1: Product type investigations

At least seven tasks should be performed at this stage: (1) document characteristics of the existing product (e.g., parts, operation, assembly and packaging), (2) investigate the design features and accompanying information for similar or competitive products, (3) collect data on accidents for both this product and similar or competitive products, (4) identify human factors and safety research addressing this type of product, (5) identify applicable standards and regulations, (6) analyse government and commercial media attention to this type of product (including recall information) and (7) research the litigation history for this and similar products.

Level 2: Product use and user group research

At least seven tasks should be performed at this stage: (1) determine appropriate methods for use of product (including assembly, installation, use and maintenance), (2) identify existing and potential product user groups, (3) research consumer use, misuse, and knowledge of product or similar products, (4) research user perceptions of product hazards, (5) identify hazards associated with intended use(s) and foreseeable misuse(s) of product, (6) analyse cognitive and behavioural demands during product use and (7) identify likely user errors, their consequences and potential remedies.

After completing the analyses in Levels 1 and 2, product design changes should be considered before proceeding further. In the traditional safety engineering sense, this could be called “engineering the hazard out of the product”. Some modifications may be for the health of the consumer, and some for the benefit of the company as it attempts to produce a marketing success.

Level 3: Information design criteria and prototypes

In Level 3 at least nine tasks are performed: (1) determine from the standards and requirements applying to the particular product which if any of those requirements impose design or performance criteria on this part of the information design, (2) determine those types of tasks for which information is to be provided to users (e.g., operation, assembly, maintenance and disposal), (3) for each type of task information, determine messages to be conveyed to user, (4) determine the mode of communication appropriate for each message (e.g., text, symbols, signals or product features), (5) determine temporal and spatial location of individual messages, (6) develop desired features of information based on messages, modes and placements developed in previous steps, (7) develop prototypes of individual components of product information system (e.g., manuals, labels, warnings, tags, advertisements, packaging and signs), (8) verify that there is consistency across the various types of information (e.g., manuals, advertisements, tags and packaging) and (9) verify that products with other brand names or similar existing products from the same company have consistent information.

After having proceeded through Levels 1, 2 and 3, the researcher will have developed the format and content of information expected to be appropriate. At this point, the researcher may want to provide initial recommendations regarding the redesign of any existing product information before moving on to Level 4.

Level 4: Evaluation and revision

In Level 4 at least six tasks are performed: (1) define evaluation parameters for each prototype component of the product information system, (2) develop an evaluation plan for each prototype component of the product information system, (3) select representative users, installers and so on, to participate in evaluation, (4) execute the evaluation plan, (5) modify product information prototypes and/or the design of the product based on the results obtained during evaluation (several iterations are likely to be necessary) and (6) specify the final text and artwork layout.

Level 5: Publication

Level 5, the actual publication of the information, is reviewed, approved and accomplished as specified. The purpose at this level is to confirm that specifications for designs, including designated logical groupings of material, location and quality of illustrations, and special communication features have been precisely followed, and have not been unintentionally modified by the printer. While the publication activity is usually not under the control of the person developing the information designs, we have found it necessary to verify that such designs are precisely followed, the reason being that printers have been known to take great liberties in manipulating design layout.

Level 6: Post-sale evaluations

The last level of the model deals with the post-sale evaluations, a final check to ensure that the information is indeed fulfilling the goals it was designed to achieve. The information designer as well as the manufacturer gains an opportunity for valuable and educational feedback from this process. Examples of post-sale evaluations include (1) feedback from customer satisfaction programmes, (2) potential summarization of data from warranty fulfilments and warranty response cards, (3) gathering of information from accident investigations involving the same or similar products, (4) monitoring of consensus standards and regulatory activities and (5) monitoring of safety recalls and media attention to similar products.

Theoretical Principles of Job Safety

This presentation covers the theoretical principles of job safety and the general principles for accident prevention. The presentation does not cover work-related illnesses, which, although related, are different in many respects.

Theory of Job Safety

Job safety involves the interrelationship between people and work; materials, equipment and machinery; the environment; and economic considerations such as productivity. Ideally, work should be healthful, not harmful and not unreasonably difficult. For economic reasons, as high a level of productivity as possible must be achieved.

Job safety should start in the planning stage and continue through the various phases of production. Accordingly, requirements for job safety must be asserted before work begins and be implemented throughout the work cycle, so that the results can be appraised for purposes of feedback, among other reasons. The responsibility of supervision toward maintaining the health and safety of those employed in the production process should also be considered during planning. In the manufacturing process, people and objects interact. (The term object is used in the broader sense as expressed in the customary designation “people-(machine)-environment system”. This includes not only technical instruments of work, machines and materials, but all surrounding items such as floors, stairs, electrical current, gas, dusts, atmosphere and so on.)

Worker-Job Relationships

The following three possible relationships within the manufacturing process indicate how personal injury incidents (especially accidents) and harmful working conditions are unintended effects of combining people and the objective working environment for the purpose of production.

- The relationship between the worker and the objective working environment is optimal. This means well-being, job safety and labour-saving methods for the employees as well as the reliability of the objective parts of the system, like machines. It also means no defects, accidents, incidents, near misses (potential incidents) or injuries. The result is improved productivity.

- The worker and the objective working environment are incompatible. This may be because the person is unqualified, equipment or materials are not correct for the job or the operation is poorly organized. Accordingly, the worker is unintentionally overworked or underutilized. Objective parts of the system, like machines, may become unreliable. This creates unsafe conditions and hazards with the potential for near misses (near accidents) and minor incidents resulting in delays in production flow and declining output.

- The relationship between the worker and the objective working environment is completely interrupted and a disruption results, causing damage, personal injury or both, thereby preventing output. This relationship is specifically concerned with the question of job safety in the sense of avoiding accidents.

Principles of Workplace Safety

Because it is apparent that questions of accident prevention can be solved not in isolation, but only in the context of their relationship with production and the working environment, the following principles for accident prevention can be derived:

- Accident prevention must be built into production planning with the goal of avoiding disruptions.

- The ultimate goal is to achieve a production flow that is as unhindered as possible. This results not only in reliability and the elimination of defects, but also in the workers’ well-being, labour-saving methods and job safety.

Some of the practices commonly used in the workplace to achieve job safety and which are necessary for disruption-free production include, but are not limited to the following:

- Workers and supervisors must be informed and aware of the dangers and potential hazards (e.g., through education).

- Workers must be motivated to function safely (behaviour modification).

- Workers must be able to function safely. This is accomplished through certification procedures, training and education.

- The personal working environment should be safe and healthy through the use of administrative or engineering controls, substitution of less hazardous materials or conditions, or by the use of personal protective equipment.

- Equipment, machinery and objects must function safely for their intended use, with operating controls designed to human capabilities.

- Provisions should be made for appropriate emergency response in order to limit the consequences of accidents, incidents and injuries.

The following principles are important in understanding how accident prevention concepts relate to disruption-free production:

- Accident prevention is sometimes considered a social burden instead of a major part of disruption prevention. Disruption prevention is a better motivator than accident prevention, because improved production is expected to result from disruption prevention.

- Measures to ensure workplace safety must be integrated into the measures used to ensure disruption-free production. For example, the instructions on hazards must be an integral part of the general directions governing the flow of production at the workplace.

Accident Theory

An accident (including those that entail injuries) is a sudden and unwanted event, caused by an outside influence, that causes harm to people and results from the interaction of people and objects.

Often the use of the term accident in the workplace is linked with personal injury. Damage to a machine is often referred to as a disruption or damage, but not an accident. Damage to the environment is often called an incident. Accidents, incidents and disruptions which do not result in injury or damage are known as “near accidents” or “near misses”. So while it may be considered appropriate to refer to accidents as cases of injury to workers and to define the terms incident, disruption and damage separately as they apply to objects and the environment, in the context of this article they will all be referred to as accidents.