Coal Workers' Lung Diseases

Coal miners are subject to a number of lung diseases and disorders arising from their exposure to coal mine dust. These include pneumoconiosis, chronic bronchitis and obstructive lung disease. The occurrence and severity of disease depends on the intensity and duration of dust exposure. The specific composition of the coal mine dust also has a bearing on some health outcomes.

In the developed countries, where high prevalences of lung disease existed in the past, reductions in dust levels brought about by regulation have led to substantial drops in disease prevalence since the 1970s. In addition, major reductions in the mining work force in most of those countries over recent decades, partly brought about by changes in technology and resulting improvements in productivity, will result in further reductions in overall disease levels. Miners in other countries, where coal mining is a more recent phenomenon and dust controls are less aggressive, have not been so fortunate. This problem is exacerbated by the high cost of modern mining technology, forcing the employment of large numbers of workers, many of whom are at high risk of disease development.

In the following text, each disease or disorder is considered in turn. Those specific to coal mining, such as coal workers’ pneumoconiosis are described in detail; the description of others, such as obstructive lung disease, is restricted to those aspects that relate to coal miners and dust exposure.

Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis

Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP) is the disease most commonly associated with coal mining. It is not a fast-developing disease, usually taking at least ten years to be manifested, and often much longer when exposures are low. In its initial stages it is an indicator of excessive lung dust retention, and may be associated with few symptoms or signs in itself. However, as it advances, it puts the miner at increasing risk of development of the much more serious progressive massive fibrosis (PMF).

Pathology

The classic lesion of CWP is the coal macule, a collection of dust and dust-laden macrophages around the periphery of the respiratory bronchioles. The macules contain minimal collagen and are thus usually not palpable. They are about 1 to 5 mm in size, and are frequently accompanied by an enlargement of the adjacent air spaces, termed focal emphysema. Though often very numerous, they are not usually evident on a chest radiograph.

Another lesion associated with CWP is the coal nodule. These larger lesions are palpable and contain a mixture of dust-laden macrophages, collagen and reticulin. The presence of coal nodules, with or without silicotic nodules (see below), indicates lung fibrosis, and is largely responsible for the opacities seen on chest radiographs. Macronodules (7 to 20 mm) in size may coalesce to form progressive massive fibrosis (see below), or PMF may develop from a single macronodule.

Silicotic nodules (described under silicosis) have been found in a significant minority of underground coal miners. For most, the cause may rest simply with the silica present in the coal dust, although exposure to pure silica in some jobs is certainly an important factor (e.g., among surface drillers, underground motormen and roof bolters).

Radiography

The most useful indicator of CWP in miners during life is obtained using the routine chest radiograph. Dust deposits and the nodular tissue reactions attenuate the x-ray beam and result in opacities on the film. The profusion of these opacities can be assessed systematically by using a standardized method of radiograph description such as that disseminated by the ILO and described else in this chapter. In this method, individual posterior-anterior films are compared to standard radiographs showing increasing profusion of small opacities, and the film classified into one of four major categories (0, 1, 2, 3) based on its similarity to the standard. A secondary classification is also made, depending on the reader’s assessment of the film’s similarity to adjacent ILO categories. Other aspects of the opacities, such as size, shape and region of occurrence in the lung are also noted. Some countries, such as China and Japan, have developed similar systems for systematic radiograph description or interpretation that are particularly suited to their own needs.

Traditionally, small rounded types of opacity have been associated with coal mining. However, more recent data indicate that irregular types can also result from exposure to coal mine dust. The opacities of CWP and silicosis are often indistinguishable on the radiograph. However, there is some evidence that larger sized opacities (type r) more often indicate silicosis.

It is important to note that a substantial amount of pathologic abnormality related to pneumoconiosis may be present in the lung before it can be detected on the routine chest x ray. This is particularly true for macular deposition, but it becomes progressively less true with greater profusion and size of nodules. Concomitant emphysema may also reduce the visibility of lesions on the chest x ray. Computerized tomography (CT)—particularly high-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT)—may permit visualization of abnormalities not clearly evident on routine chest x rays, although CT is not necessary for routine clinical diagnosis of miners’ lung diseases and is not indicated for medical surveillance of miners.

Clinical aspects

The development of CWP, although a marker of excessive lung dust retention, in itself is often unaccompanied by any overt clinical signs. This should not, however, be taken to imply that the inhalation of coal mine dust is without risk, for it is now well known that other lung diseases can arise from dust exposure. Pulmonary hypertension is more often noted in miners who develop airflow obstruction in association with CWP. Moreover, once CWP has developed, it usually progresses unless dust exposure ceases, and may progress thereafter. It also puts the miner at greatly increased risk of development of the clinically ominous PMF, with the likelihood of subsequent impairment, disability and premature mortality.

Disease mechanisms

Development of the earliest change of CWP, the dust macule, represents the effects of dust deposition and accumulation. The subsequent stage, that is, the development of nodules, results from the lung’s inflammatory and fibrotic reaction to the dust. In this, the roles of silica and non-silica dust have long been debated. On the one hand, silica dust is known to be considerably more toxic than coal dust. Yet, on the other hand, epidemiological studies have shown no strong evidence implicating silica exposure in CWP prevalence or incidence. Indeed, it seems that almost an inverse relationship exists, in that disease levels tend to be elevated where silica levels are lower (e.g., in areas where anthracite is mined). Recently, some understanding of this paradox has been gained through studies of particle characteristics. These studies indicate that not only the quantity of silica present in the dust (as measured conventionally using infrared spectrometry or x-ray diffraction), but also the bioavailability of the surface of the silica particles may be related to toxicity. For example, clay coating (occlusion) may play an important modifying role. Another important factor under current investigation concerns surface charge in the form of free radicals and the effects of “freshly fractured” versus “aged” silica-containing dusts.

Surveillance and epidemiology

The prevalence of CWP among underground miners varies with the kind of job, tenure and age. A recent study of US coal miners revealed that from 1970 to 1972 about 25 to 40% of working coal miners had category 1 or greater small rounded opacities after 30 or more years in mining. This prevalence reflects exposure to levels of 6 mg/m3 or more of respirable dust among coal face workers prior to that time. The introduction of a dust limit of 3 mg/m3 in 1969, with a reduction to 2 mg/m3 in 1972 has led to a decline in disease prevalence to about half of the former levels. Declines related to dust control have been noted elsewhere, for example, in the United Kingdom and Australia. Unfortunately, these gains have been counterbalanced by temporal increases in prevalence elsewhere.

An exposure-response relationship for prevalence or incidence of CWP and dust exposure has been demonstrated in a number of studies. These have shown that the primary significant dust exposure variable is exposure to mixed mine dust. Intensive studies by British researchers failed to disclose any major influence of silica exposure, as long as the percentage of silica was less than about 5%. Coal rank (percentage carbon) is another important predictor of CWP development. Studies in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and elsewhere have given clear indications that the prevalence and incidence of CWP increases markedly with coal rank, these being substantially greater where anthracite (high rank) coal is mined. No other environmental variables have been found to exert any major effects on CWP development. Miner age appears to have some bearing on disease development, since older miners appear to be at increased risk. However, it is not entirely clear whether this implies that older miners are more susceptible, whether it is a residence time effect, or is simply an artefact (the age effect might reflect underestimation of exposure estimates for older miners, for example). Cigarette smoking does not appear to increase the risk of CWP development.

Research in which miners were followed-up with chest radiographs every five years shows that the risk of developing PMF over the five years is clearly related to the category of CWP as revealed on the initial chest x ray. Since the risk at category 2 is much greater than that at category 1, conventional wisdom at one time was that miners should be prevented from reaching category 2 if at all possible. However, in most mines there are usually many more miners with category 1 CWP compared to category 2. Thus, the lower risk for category 1 compared to category 2 is offset somewhat by the larger numbers of miners with category 1. On this showing, it has become clear that all pneumoconiosis should be prevented.

Mortality

Miners as a group have been observed to have increased risk of death from non-malignant respiratory diseases, and there is evidence that the mortality among miners with CWP is somewhat increased over those of similar age without the disease. However, the effect is smaller than the excess seen for miners with PMF (see below).

Prevention

The only protection against CWP is minimization of dust exposure. If possible, this should be achieved by dust suppression methods, such as ventilation and water sprays, rather than by respirator use or administrative controls, for example, worker rotation. In this respect, there is now good evidence that regulatory actions in some countries to reduce the level of dust, taken around the 1970s, has resulted in greatly reduced levels of disease. Transfer of workers with early signs of CWP to less dusty jobs is a prudent action, although there is little practical evidence that such programmes have succeeded in preventing disease progression. For this reason, dust suppression must remain the primary method of disease prevention.

Ongoing, aggressive monitoring of dust exposure and the conscious exertion of control efforts can be supplemented by health screening surveillance of miners. If miners are found to develop dust-related diseases, efforts at exposure control should be intensified throughout the workplace and miners with dust effects should be offered work in low-dust areas of the mine environment.

Treatment

Although several forms of treatment have been tried, including aluminium powder inhalation, and the administration of tetrandine, no treatment is known that effectively reverses or slows the fibrotic process in the lung. Currently, primarily in China, but elsewhere also, whole-lung lavage is being tried with the intent of reducing the total lung dust burden. Although the procedure can result in the removal of a considerable amount of dust, its risks, benefits and role in the management of miners’ health are unclear.

In other respects, treatment should be directed towards preventing complications, maximizing the miners’ functional status and alleviating their symptoms, whether due to CWP or to other, concomitant respiratory diseases. In general, miners who develop dust-induced lung diseases should evaluate their current dust exposures and utilize the resources of government and labour organizations to find the avenues available to reduce all adverse respiratory exposures. For miners who smoke, smoking cessation is an initial step in personal exposure management. Prevention of infectious complications of chronic lung disease with available pneumococcal and yearly influenza vaccines is suggested. Early investigation of symptoms of lung infection, with particular attention to mycobacterial disease, is also recommended. The treatments for acute bronchitis, bronchospasm and congestive heart failure among miners are similar to those for patients without dust-related disease.

Progressive Massive Fibrosis

PMF, sometimes referred to as complicated pneumoconiosis, is diagnosed when one or more large fibrotic lesions (whose definition depends on the mode of detection) are present in one or both lungs. As its name implies, PMF often becomes more severe over time, even in the absence of additional dust exposure. It can also develop after dust exposure has ceased, and may often cause disability and premature mortality.

Pathology

PMF lesions may be unilateral or bilateral, and are most often found in the upper or middle lobes of the lung. The lesions are formed of collagen, reticulin, coal mine dust and dust-laden macrophages, while the centre may contain a black liquid which cavitates on occasion. US pathology standards require the lesions to be 2 cm in size or larger to be identified as PMF entities in surgical or autopsy specimens.

Radiology

Large opacities >>1 cm) on the radiograph, coupled with a history of extensive coal mine dust exposure, are taken to imply the presence of PMF. However, it is important that other diseases such as lung cancer, tuberculosis and granulomas be considered. Large opacities are usually seen on a background of small opacities, but development of PMF from a category 0 profusion has been noted over a five-year period.

Clinical aspects

Diagnostic possibilities for each individual miner with large chest opacities must be appropriately evaluated. Clinically stable miners with bilateral lesions in the typical upper-lung distribution and with pre-existing simple CWP may present little diagnostic challenge. However, miners with progressive symptoms, risk factors for other disorders (e.g., tuberculosis), or atypical clinical features should undergo a thorough appropriate examination before the diagnostician attributes the lesions to PMF.

Dyspnoea and other respiratory symptoms often accompany PMF, but may not necessarily be due to the disease itself. Congestive heart failure (due to pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale) is a not infrequent complication.

Disease mechanisms

Despite extensive research, the actual cause of PMF development remains unclear. Over the years, various hypotheses have been proposed, but none is fully satisfactory. One prominent theory was that tuberculosis played a role. Indeed, tuberculosis is often present in miners with PMF, particularly in the developing countries. However, PMF has been found to develop in miners in whom there was no sign of tuberculosis, and tuberculin reactivity has not been found to be elevated in miners with pneumoconiosis. Despite investigation, consistent evidence of the role of the immune system in PMF development is lacking.

Surveillance and epidemiology

As with CWP, PMF levels have been declining in countries which have strict dust control regulations and programmes. A recent study of US miners revealed that about 2% of coal miners working underground had PMF after 30 or more years in mining (although this figure may have been biased by affected miners leaving the work force).

Exposure-response investigations of PMF have shown that exposure to coal mine dust, category of CWP, coal rank and age are the primary determinants of disease development. As with CWP, epidemiological studies have found no major effect of silica dust. Although it was thought at one time that PMF developed only on a background of the small opacities of CWP, recently this has been found not to be the case. Miners with an initial chest x ray showing category 0 CWP have been shown to develop PMF over five years, with the risk increasing with their cumulative dust exposure. Also, miners may develop PMF after cessation of dust exposure.

Mortality

PMF leads to premature mortality, the prognosis worsening with increasing stage of the disease. A recent study showed that miners with category C PMF had only one-fourth the rate of survival over 22 years compared to miners with no pneumoconiosis. This effect was manifested over all age groups.

Prevention

Avoidance of dust exposure is the only way to prevent PMF. Since the risk of its development increases sharply with increasing category of simple CWP, a strategy for secondary prevention of PMF is for miners to undergo periodic chest x rays and to terminate or reduce their exposure if simple CWP is detected. Although this approach appears valid and has been adopted in certain jurisdictions, its effectiveness has not been evaluated systematically.

Treatment

There is no known treatment for PMF. Medical care should be organized around ameliorating the condition and associated lung illnesses, while protecting against infectious complications. Although maintaining functional stability may be more difficult in patients with PMF, in other respects, management is similar to simple CWP.

Obstructive Lung Disease

There is now consistent and convincing evidence of a relationship between lung function loss and dust exposure. Various studies in different countries have looked at the influence of dust exposure on absolute values of, and temporal changes in, measurements of ventilatory function, such as forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and flow rates. All have found evidence that dust exposure leads to a reduction in lung function, and the results have been strikingly similar for several recent British and US investigations. These indicate that over the course of a year, dust exposure at the coal face brings about, on average, a reduction in lung function equivalent to smoking half a pack of cigarettes each day. The studies also demonstrate that effects vary, and a given miner may develop effects equal to, or worse than, those expected from cigarette smoking, particularly if the individual has experienced higher dust exposures.

The effects of dust exposure have been found in both those who have never smoked and in current smokers. Moreover, there is no evidence that smoking exacerbates the dust exposure effect. Rather, studies have generally shown a slightly smaller effect in current smokers, a result that may be due to healthy worker selection. It is important to note that the relationship between dust exposure and ventilatory decline appears to exist independently of pneumoconiosis. That is, it is not a requirement that pneumoconiosis be present for there to be reduced lung function. To the contrary, it appears rather that the inhaled dust can act along multiple pathways, leading to pneumoconiosis in some miners, to obstruction in others and to multiple outcomes in yet others. In contrast to miners with CWP alone, miners with respiratory symptoms have significantly lower lung function, after standardization for age, smoking, dust exposure and other factors.

Recent work on ventilatory function changes has involved the exploration of longitudinal changes. The results indicate that there may be a non-linear trend of decline over time in new miners, a high initial rate of loss being followed by a more moderate decline with continued exposure. Furthermore, there is evidence that miners who react to the dust may choose, if possible, to remove themselves from the heavier exposures.

Chronic Bronchitis

Respiratory symptoms, such as chronic cough and phlegm production, are a frequent consequence of work in coal mining, most studies showing an excess prevalence compared to non-exposed control groups. Moreover, the prevalence and incidence of respiratory symptoms has been shown to increase with cumulative dust exposure, after taking into account age and smoking. The presence of symptoms appears to be associated with a reduction in lung function over and above that due to dust exposure and other putative causes. This suggests that dust exposure may be instrumental in initiating certain disease processes that then progress regardless of further exposure. A relationship between bronchial gland size and dust exposure has been demonstrated pathologically, and it has been found that mortality from bronchitis and emphysema increases with increasing cumulative dust exposure.

Emphysema

Pathological studies have repeatedly found an excess of emphysema in coal miners compared to control groups. Moreover, the degree of emphysema has been found to be related both to the amount of dust in the lungs and to pathological assessments of pneumoconiosis. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that there is evidence that the presence of emphysema is related to dust exposure and to the percentage of predicted FEV1. Hence, these results are consistent with the view that dust exposure can lead to disability through causing emphysema.

The form of emphysema most clearly associated with coal mining is focal emphysema. This consists of zones of enlarged air spaces, 1 to 2 mm in size, adjacent to dust macules surrounding the respiratory bronchioles. The current thinking is that the emphysema is formed from tissue destruction, rather than from distension or dilation. Apart from focal emphysema, there is evidence that centriacinar emphysema has an occupational origin, and that total emphysema, (i.e., the extent of all types) is correlated with tenure in mining, in those who have never smoked as well as in smokers. There is no evidence that smoking potentiates the dust exposure/emphysema relationship. However, there are indications of an inverse relationship between the silica content of lungs and the presence of emphysema.

The issue of emphysema has long been controversial, with some stating that selection bias and smoking make interpretation of pathological studies difficult. In addition, some consider that focal emphysema has only trivial effects on lung function. However, pathological studies undertaken since the 1980s have been responsive to earlier criticisms, and indicate that the effect of dust exposure may be more significant for miners’ health than previously thought. This point of view is supported by recent findings that mortality from bronchitis and emphysema is related to cumulative dust exposure.

Silicosis

Silicosis, though associated more with industries other than coal mining, can occur in coal miners. In underground mines, it is found most frequently in workers in certain jobs where exposure to pure silica typically occurs. Such workers include roof bolters, who drill into the ceiling rock, which can often be sandstone or other rock with high silica content; motormen, drivers of rail transport who are exposed to the dust generated by sand placed on the tracks to lend traction; and rock drillers, who are involved in mine development. Rock drillers at surface coal mines have been shown to be at particular risk in the United States, with some developing acute silicosis after only a few years of exposure. Based on pathological evidence, as noted below, some degree of silicosis may afflict many more coal miners than just those working the jobs noted above.

Silicotic nodules in coal miners are similar in nature to those observed elsewhere, and consist of a whorled pattern of collagen and reticulin. One large autopsy study has revealed that about 13% of coal miners had silicotic nodules in their lungs. Although one job, (that of motorman) was notable for having a much higher prevalence of silicotic nodules (25%), there was little variation in the prevalence among miners in other jobs, suggesting that the silica in the mixed mine dust was responsible.

Silicosis cannot be reliably differentiated from coal workers’ pneumoconiosis on a radiograph. However, there is some evidence that the larger type of small opacities (type r) are indicative of silicosis.

Rheumatoid Pneumoconiosis

Rheumatoid pneumoconiosis, one variant of which is called Caplan’s syndrome, is the term used for a condition affecting dust-exposed workers who develop multiple large radiographic shadows. Pathologically, these lesions resemble rheumatoid nodules rather than PMF lesions, and often arise over a short time interval. Active arthritis or the presence of circulating rheumatoid factor are generally found, but occasionally are absent.

Lung Cancer

Included in the occupational exposures suffered by coal miners are a number of substances that are potential carcinogens. Some of these are silica and benzo(a)pyrenes. Yet, there is no clear evidence of an excess of deaths from lung cancer in coal miners. One obvious explanation for this is that coal miners are forbidden to smoke underground because of the danger of fires and explosions. However, the fact that no exposure-response relationship between lung cancer and dust exposure has been detected suggests that coal mine dust is not a major cause of lung cancer in the industry.

Regulatory Limits on Dust Exposure

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended a “tentative health-based exposure limit” for respirable coal mine dust (with less than 6% respirable quartz) ranging from 0.5 to 4 mg/m3. WHO suggests a 2 in 1,000 risk of PMF over a working lifetime as a criterion, and recommends that mine-based environmental factors, including coal rank, percentage of quartz and particle size should be taken into account when setting limits.

Currently, among the major coal-producing countries, limits are based on regulating coal dust alone (e.g., 3.8 mg/m3 in the United Kingdom, 5 mg/m3 in Australia and Canada) or on regulating a mixture of coal and silica as in the United States (2 mg/m3 when the per cent quartz is 5 or less, or (10 mg/m3)/per cent SiO2), or in Germany (4 mg/m3 when the per cent quartz is 5 or less, or 0.15 mg/m3 otherwise), or on regulating pure quartz (e.g., Poland, with a 0.05 mg/m3 limit).

Silicosis

Silicosis is a fibrotic disease of the lungs caused by the inhalation, retention and pulmonary reaction to crystalline silica. Despite knowledge of the cause of this disorder—respiratory exposures to silica containing dusts—this serious and potentially fatal occupational lung disease remains prevalent throughout the world. Silica, or silicon dioxide, is the predominant component of the earth’s crust. Occupational exposure to silica particles of respirable size (aerodynamic diameter of 0.5 to 5μm) is associated with mining, quarrying, drilling, tunnelling and abrasive blasting with quartz containing materials (sandblasting). Silica exposure also poses a hazard to stonecutters, and pottery, foundry, ground silica and refractory workers. Because crystalline silica exposure is so widespread and silica sand is an inexpensive and versatile component of many manufacturing processes, millions of workers throughout the world are at risk of the disease. The true prevalence of the disease is unknown.

Definition

Silicosis is an occupational lung disease attributable to the inhalation of silicon dioxide, commonly known as silica, in crystalline forms, usually as quartz, but also as other important crystalline forms of silica, for example, cristobalite and tridymite. These forms are also called “free silica” to distinguish them from the silicates. The silica content in different rock formations, such as sandstone, granite and slate, varies from 20 to nearly 100%.

Workers in High-Risk Occupations and Industries

Although silicosis is an ancient disease, new cases are still reported in both the developed and developing world. In the early part of this century, silicosis was a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Contemporary workers are still exposed to silica dust in a variety of occupations—and when new technology lacks adequate dust control, exposures may be to more hazardous dust levels and particles than in non-mechanized work settings. Whenever the earth’s crust is disturbed and silica-containing rock or sand is used or processed, there are potential respiratory risks for workers. Reports continue of silicosis from industries and work settings not previously recognized to be at risk, reflecting the nearly ubiquitous presence of silica. Indeed, due to the latency and chronicity of this disorder, including the development and progression of silicosis after exposure has ceased, some workers with current exposures may not manifest disease until the next century. In many countries throughout the world, mining, quarrying, tunnelling, abrasive blasting and foundry work continue to present major risks for silica exposure, and epidemics of silicosis continue to occur, even in developed nations.

Forms of Silicosis—Exposure History and Clinicopathologic Descriptions

Chronic, accelerated and acute forms of silicosis are commonly described. These clinical and pathologic expressions of the disease reflect differing exposure intensities, latency periods and natural histories. The chronic or classic form usually follows one or more decades of exposure to respirable dust containing quartz, and this may progress to progressive massive fibrosis (PMF). The accelerated form follows shorter and heavier exposures and progresses more rapidly. The acute form may occur after short-term, intense exposures to high levels of respirable dust with high silica content for periods that may be measured in months rather than years.

Chronic (or classic) silicosis may be asymptomatic or result in insidiously progressive exertional dyspnoea or cough (often mistakenly attributed to the ageing process). It presents as a radiographic abnormality with small (<10 mm), rounded opacities predominantly in the upper lobes. A history of 15 years or more since onset of exposure is common. The pathologic hallmark of the chronic form is the silicotic nodule. The lesion is characterized by a cell-free central area of concentrically arranged, whorled hyalinized collagen fibers, surrounded by cellular connective tissue with reticulin fibers. Chronic silicosis may progress to PMF (sometimes referred to as complicated silicosis), even after exposure to silica-containing dust has ceased.

Progressive massive fibrosis is more likely to present with exertional dyspnoea. This form of disease is characterized by nodular opacities greater than 1 cm on chest radiograph and commonly will involve reduced carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, reduced arterial oxygen tension at rest or with exercise, and marked restriction on spirometry or lung volume measurement. Distortion of the bronchial tree may also lead to airway obstruction and productive cough. Recurrent bacterial infection not unlike that seen in bronchiectasis may occur. Weight loss and cavitation of the large opacities should prompt concern for tuberculosis or other mycobacterial infection. Pneumothorax may be a life-threatening complication, since the fibrotic lung may be difficult to re-expand. Hypoxaemic respiratory failure with cor pulmonale is a common terminal event.

Accelerated silicosis may appear after more intense exposures of shorter (5 to 10 years) duration. Symptoms, radiographic findings and physiological measurements are similar to those seen in the chronic form. Deterioration in lung function is more rapid, and many workers with accelerated disease may develop mycobacterial infection. Auto-immune disease, including scleroderma or systemic sclerosis, is seen with silicosis, often of the accelerated type. The progression of radiographic abnormalities and functional impairment can be very rapid when auto-immune disease is associated with silicosis.

Acute silicosis may develop within a few months to 2 years of massive silica exposure. Dramatic dyspnoea, weakness, and weight loss are often presenting symptoms. The radiographic findings of diffuse alveolar filling differ from those in the more chronic forms of silicosis. Histologic findings similar to pulmonary alveolar proteinosis have been described, and extrapulmonary (renal and hepatic) abnormalities are occasionally reported. Rapid progression to severe hypoxaemic ventilatory failure is the usual course.

Tuberculosis may complicate all forms of silicosis, but people with acute and accelerated disease may be at highest risk. Silica exposure alone, even without silicosis may also predispose to this infection. M. tuberculosis is the usual organism, but atypical mycobacteria are also seen.

Even in the absence of radiographic silicosis, silica-exposed workers may also have other diseases associated with occupational dust exposure, such as chronic bronchitis and the associated emphysema. These abnormalities are associated with many occupational mineral dust exposures, including dusts containing silica.

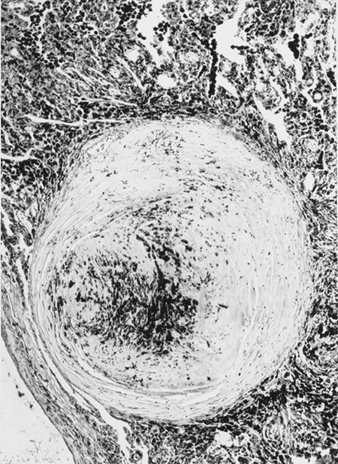

Pathogenesis and the Association with Tuberculosis

The precise pathogenesis of silicosis is uncertain, but an abundance of evidence implicates the interaction between the pulmonary alveolar macrophage and silica particles deposited in the lung. Surface properties of the silica particle appear to promote macrophage activation. These cells then release chemotactic factors and inflammatory mediators that result in a further cellular response by polymorphonuclear leukocytes, lymphocytes and additional macrophages. Fibroblast-stimulating factors are released that promote hyalinization and collagen deposition. The resulting pathologic silicotic lesion is the hyaline nodule, containing a central acellular zone with free silica surrounded by whorls of collagen and fibroblasts, and an active peripheral zone composed of macrophages, fibroblasts, plasma cells, and additional free silica as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Typical silicotic nodule, microscopic section. Courtesy of Dr. V. Vallyathan.

The precise properties of silica particles that evoke the pulmonary response described above are not known, but surface characteristics may be important. The nature and the extent of the biological response are in general related to the intensity of the exposure; however, there is growing evidence that freshly fractured silica may be more toxic than aged dust containing silica, an effect perhaps related to reactive radical groups on the cleavage planes of freshly fractured silica. This may offer a pathogenic explanation for the observation of cases of advanced disease in both sandblasters and rock drillers where exposures to recently fractured silica are particularly intense.

The initiating toxic insult may occur with minimal immunological reaction; however, a sustained immunological response to the insult may be important in some of the chronic manifestations of silicosis. For example, antinuclear antibodies may occur in accelerated silicosis and scleroderma, as well as other collagen diseases in workers who have been exposed to silica. The susceptibility of silicotic workers to infections, such as tuberculosis and Nocardia asteroides, is likely related to the toxic effect of silica on pulmonary macrophages.

The link between silicosis and tuberculosis has been recognized for nearly a century. Active tuberculosis in silicotic workers may exceed 20% when community prevalence of tuberculosis is high. Again, people with acute silicosis appear to be at considerably higher risk.

Clinical Picture of Silicosis

The primary symptom is usually dyspnoea, first noted with activity or exercise and later at rest as the pulmonary reserve of the lung is lost. However, in the absence of other respiratory disease, shortness of breath may be absent and the presentation may be an asymptomatic worker with an abnormal chest radiograph. The radiograph may at times show quite advanced disease with only minimal symptoms. The appearance or progression of dyspnoea may herald the development of complications including tuberculosis, airways obstruction or PMF. Cough is often present secondary to chronic bronchitis from occupational dust exposure, tobacco use, or both. Cough may at times also be attributed to pressure from large masses of silicotic lymph nodes on the trachea or mainstem bronchi.

Other chest symptoms are less common than dyspnoea and cough. Haemoptysis is rare and should raise concern for complicating disorders. Wheeze and chest tightness may occur usually as part of associated obstructive airways disease or bronchitis. Chest pain and finger clubbing are not features of silicosis. Systemic symptoms, such as fever and weight loss, suggest complicating infection or neoplastic disease. Advanced forms of silicosis are associated with progressive respiratory failure with or without cor pulmonale. Few physical signs may be noted unless complications are present.

Radiographic Patterns and Functional Pulmonary Abnormalities

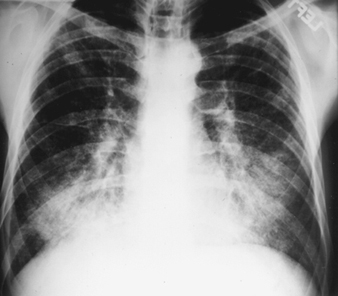

The earliest radiographic signs of uncomplicated silicosis are generally small rounded opacities. These can be described by the ILO International Classification of Radiographs of Pneumoconioses by size, shape and profusion category. In silicosis, “q” and “r” type opacities dominate. Other patterns including linear or irregular shadows have also been described. The opacities seen on the radiograph represent the summation of pathologic silicotic nodules. They are usually found predominantly in the upper zones and may later progress to involve other zones. Hilar lymphadenopathy is also noted sometimes in advance of nodular parenchymal shadows. Egg shell calcification is strongly suggestive of silicosis, although this feature is seen infrequently. PMF is characterized by the formation of large opacities. These large lesions can be described by size using the ILO classification as categories A, B or C. Large opacities or PMF lesions tend to contract, usually to the upper lobes, leaving areas of compensatory emphysema at their margins and often in the lung bases. As a result, previously evident small rounded opacities may disappear at times or be less prominent. Pleural abnormalities may occur but are not a frequent radiographic feature in silicosis. Large opacities may also pose concern regarding neoplasm and radiographic distinction in the absence of old films may be difficult. All lesions that cavitate or change rapidly should be evaluated for active tuberculosis. Acute silicosis may present with a radiologic alveolar filling pattern with rapid development of PMF or complicated mass lesions. See figures 2 and 3.

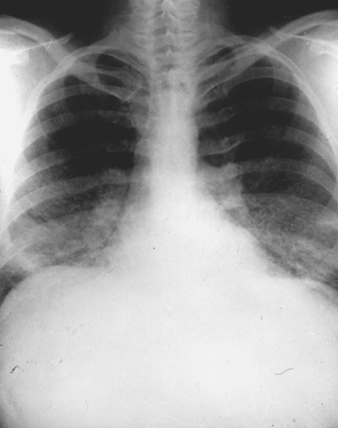

Figure 2. Chest radiograph, acute silico-proteinosis in a surface coal mine driller. Courtesy of Dr. NL Lapp and Dr. DE Banks.

Figure 3. Chest radiograph, complicated silicosis demonstrating progressive massive fibrosis.

Pulmonary function tests, such as spirometry and diffusing capacity, are helpful for the clinical evaluation of people with suspected silicosis. Spirometry may also be of value in early recognition of the health effects from occupational dust exposures, as it may detect physiologic abnormalities that may precede radiologic changes. No solely characteristic pattern of ventilatory impairment is present in silicosis. Spirometry may be normal, or when abnormal, the tracings may show obstruction, restriction or a mixed pattern. Obstruction may indeed be the more common finding. These changes tend to be more marked with advanced radiologic categories. However, poor correlation exists between radiographic abnormalities and ventilatory impairment. In acute and accelerated silicosis, functional changes are more marked and progression is more rapid. In acute silicosis, radiologic progression is accompanied by increasing ventilatory impairment and gas exchange abnormalities, which leads to respiratory failure and eventually to death from intractable hypoxaemia.

Complications and Special Diagnostic Issues

With a history of exposure and a characteristic radiograph, the diagnosis of silicosis is generally not difficult to establish. Challenges arise only when the radiologic features are unusual or the history of exposure is not recognized. Lung biopsy is rarely required to establish the diagnosis. However, tissue samples are helpful in some clinical settings when complications are present or the differential diagnosis includes tuberculosis, neoplasm or PMF. Biopsy material should be sent for culture, and in research settings, dust analysis may be a useful additional measure. When tissue is required, open lung biopsy is generally necessary for adequate material for examination.

Vigilance for infectious complications, especially tuberculosis, cannot be overemphasized, and symptoms of change in cough or hemoptysis, and fever or weight loss should trigger a work-up to exclude this treatable problem.

Substantial concern and interest about the relationship between silica exposure, silicosis and cancer of the lung continues to stimulate debate and further research. In October of 1996, a committere of The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified crystalline silica as a Group I carcinogen, reaching this conclusion based on “sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in humans”. Uncertainty over the pathogenic mechanisms for the development of lung cancer in silica-exposed populations exists, and the possible relationship between silicosis (or lung fibrosis) and cancer in exposed workers continues to be studied. Regardless of the mechanism that may be responsible for neoplastic events, the known association between silica exposures and silicosis dictates controlling and reducing exposures to workers at risk for this disease.

Prevention of Silicosis

Prevention remains the cornerstone of eliminating this occupational lung disease. The use of improved ventilation and local exhaust, process enclosure, wet techniques, personal protection including the proper selection of respirators, and where possible, industrial substitution of agents less hazardous than silica all reduce exposure. The education of workers and employers regarding the hazards of silica dust exposure and measures to control exposure is also important.

If silicosis is recognized in a worker, removal from continuing exposure is advisable. Unfortunately, the disease may progress even without further silica exposure. Additionally, finding a case of silicosis, especially the acute or accelerated form, should prompt a workplace evaluation to protect other workers also at risk.

Screening and Surveillance

Silica and other mineral-dust exposed workers should have periodic screening for adverse health effects as a supplement to, but not a substitute for, dust exposure control. Such screening commonly includes evaluations for respiratory symptoms, lung function abnormalities, and neoplastic disease. Evaluations for tuberculosis infection should also be performed. In addition to individual worker screening, data from groups of workers should be collected for surveillance and prevention activities. Guidance for these types of studies is included in the list of suggested readings.

Therapy, Management of Complications and Control of Silicosis

When prevention has been unsuccessful and silicosis has developed, therapy is directed largely at complications of the disease. Therapeutic measures are similar to those commonly used in the management of airway obstruction, infection, pneumothorax, hypoxaemia, and respiratory failure complicating other pulmonary disease. Historically, the inhalation of aerosolized aluminium has been unsuccessful as a specific therapy for silicosis. Polyvinyl pyridine-N-oxide, a polymer that has protected experiment animals, is not available for use in humans. Recent laboratory work with tetrandrine has shown in vivo reduction in fibrosis and collagen synthesis in silica exposed animals treated with this drug. However, strong evidence of human efficacy is currently lacking, and there are concerns about the potential toxicity, including the mutagenicity, of this drug. Because of the high prevalence of disease in some countries, investigations of combinations of drugs and other interventions continue. Currently, no successful approach has emerged, and the search for a specific therapy for silicosis to date has been unrewarding.

Further exposure is undesirable, and advice on leaving or changing the current job should be given with information about past and present exposure conditions.

In the medical management of silicosis, vigilance for complicating infection, especially tuberculosis, is critical. The use of BCG in the tuberculin-negative silicotic patient is not recommended, but the use of preventive isoniazid (INH) therapy in the tuberculin-positive silicotic subject is advised in countries where the prevalence of tuberculosis is low. The diagnosis of active tuberculosis infection in patients with silicosis can be difficult. Clinical symptoms of weight loss, fever, sweats and malaise should prompt radiographic evaluation and sputum acid-fast bacilli strains and cultures. Radiographic changes, including enlargement or cavitation in conglomerate lesions or nodular opacities, are of particular concern. Bacteriological studies on expectorated sputum may not always be reliable in silicotuberculosis. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy for additional specimens for culture and study may often be helpful in establishing a diagnosis of active disease. The use of multidrug therapy for suspected active disease in silicotics is justified at a lower level of suspicion than in the non-silicotic subject, due to the difficulty in firmly establishing evidence for active infection. Rifampin therapy appears to have enhanced the success rate of treatment of silicosis complicated by tuberculosis, and in some recent studies response to short-term therapy was comparable in cases of silicotuberculosis to that in matched cases of primary tuberculosis.

Ventilatory support for respiratory failure is indicated when precipitated by a treatable complication. Pneumothorax, spontaneous and ventilator-related, is usually treated by chest tube insertion. Bronchopleural fistula may develop, and surgical consultation and management should be considered.

Acute silicosis may rapidly progress to respiratory failure. When this disease resembles pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and severe hypoxaemia is present, aggressive therapy has included massive whole-lung lavage with the patient under general anaesthesia in an attempt to improve gas exchange and remove alveolar debris. Although appealing in concept, the efficacy of whole lung lavage has not been established. Glucocorticoid therapy has also been used for acute silicosis; however, it is still of unproven benefit.

Some young patients with end-stage silicosis may be considered candidates for lung or heart-lung transplantation by centres experienced with this expensive and high-risk procedure. Early referral and evaluation for this intervention may be offered to selected patients.

The discussion of an aggressive and high-technology therapeutic intervention such as transplantation serves dramatically to underscore the serious and potentially fatal nature of silicosis, as well as to emphasize the crucial role for primary prevention. The control of silicosis ultimately depends upon the reduction and control of workplace dust exposures. This is accomplished by rigorous and conscientious application of fundamental occupational hygiene and engineering principles, with a commitment to the preservation of worker health.

Aetiopathogensis of pneumoconioses

Pneumoconioses have been recognized as occupational diseases for a long time. Substantial efforts have been directed to research, primary prevention and medical management. But physicians and hygienists report that the problem is still present in both industrialized and industrializing countries (Valiante, Richards and Kinsley 1992; Markowitz 1992). As there is strong evidence that the three main industrial minerals responsible for the pneumoconioses (asbestos, coal and silica) will continue to have some economical importance, thus further entailing possible exposure, it is expected that the problem will continue to be of some magnitude throughout the world, particularly among underserved populations in small industries and small mining operations. Practical difficulties in primary prevention, or insufficient understanding of the mechanisms responsible for the induction and the progression of the disease are all factors which could possibly explain the continuing presence of the problem.

The aetiopathogenesis of pneumoconioses can be defined as the appraisal and understanding of all the phenomena occurring in the lung following the inhalation of fibrogenic dust particles. The expression cascade of events is often found in the literature on the subject. The cascade is a series of events that first exposure and at its farthest extent progresses to the disease in its more severe forms. If we except the rare forms of accelerated silicosis, which can develop after only a few months of exposure, most of the pneumoconioses develop following exposure periods measured in decades rather than years. This is especially true nowadays in workplaces adopting modern standards of prevention. Aetiopathogenesis phenomena should thus be analysed in terms of its long-term dynamics.

In the last 20 years, a large amount of information has become available on the numerous and complex pulmonary reactions involved in interstitial lung fibrosis induced by several agents, including mineral dusts. These reactions were described at the biochemical and cellular level (Richards, Masek and Brown 1991). Contributions were made by not only physicists and experimental pathologists but also by clinicians who used bronchoalveolar lavage extensively as a new pulmonary technique of investigation. These studies pictured aetiopathogenesis as a very complex entity, which can nonetheless be broken down to reveal several facets: (1) the inhalation itself of dust particles and the consequent constitution and significance of the pulmonary burden (exposure-dose-response relationships), (2) the physicochemical characteristics of the fibrogenic particles, (3) biochemical and cellular reactions inducing the fundamental lesions of the pneumoconioses and (4) the determinants of progression and complication. The later facet must not be ignored, since the more severe forms of pneumoconioses are the ones which entail impairment and disability.

A detailed analysis of the aetiopathogenesis of the pneumoconioses is beyond the scope of this article. One would need to distinguish the several types of dust and to go deeply into numerous specialized areas, some of which are still the subject of active research. But interesting general notions emerge from the currently available amount of knowledge on the subject. They will be presented here through the four “facets” previously mentioned and the bibliography will refer the interested reader to more specialized texts. Examples will be essentially given for the three main and most documented pneumoconioses: asbestosis, coal workers’ pneumoconioses (CWP) and silicosis. Possible impacts on prevention will be discussed.

Exposure-Dose-Response Relationships

Pneumoconioses result from the inhalation of certain fibrogenic dust particles. In the physics of aerosols, the term dust has a very precise meaning (Hinds 1982). It refers to airborne particles obtained by mechanical comminution of a parent material in a solid state. Particles generated by other processes should not be called dust. Dust clouds in various industrial settings (e.g., mining, tunnelling, sand blasting and manufacturing) generally contain a mixture of several types of dust. The airborne dust particles do not have a uniform size. They exhibit a size distribution. Size and other physical parameters (density, shape and surface charge) determine the aerodynamic behaviour of the particles and the probability of their penetration and deposition in the several compartments of the respiratory system.

In the field of pneumoconioses, the site compartment of interest is the alveolar compartment. Airborne particles small enough to reach this compartments are referred to as respirable particles. All particles reaching the alveolar compartments are not systematically deposited, some being still present in the exhaled air. The physical mechanisms responsible for deposition are now well understood for isometric particles (Raabe 1984) as well as for fibrous particles (Sébastien 1991). The functions relating the probability of deposition to the physical parameters have been established. Respirable particles and particles deposited in the alveolar compartment have slightly different size characteristics. For non-fibrous particles, size-selective air sampling instruments and direct reading instruments are used to measure mass concentrations of respirable particles. For fibrous particles, the approach is different. The measuring technique is based upon filter collection of “total dust” and counting of fibres under the optical microscope. In this case, the size selection is made by excluding from the count the “non-respirable” fibres with dimensions exceeding predetermined criteria.

Following the deposition of particles on the alveolar surfaces there starts the so-called alveolar clearance process. Chemotactic recruitment of macrophages and phagocytosis constitute its first phases. Several clearance pathways have been described: removal of dust-laden macrophages toward the ciliated airways, interaction with the epithelial cells and transfer of free particles through the alveolar membrane, phagocytosis by interstitial macrophages, sequestration into the interstitial area and transportation to the lymph nodes (Lauweryns and Baert 1977). Clearance pathways have specific kinetics. Not only the exposure regimen, but also the physicochemical characteristics of the deposited particles, trigger the activation of the different pathways responsible for the lung’s retention of such contaminants.

The notion of a retention pattern specific to each type of dust is rather new, but is now sufficiently established to be integrated into aetiopathogenesis schemes. For example, this author has found that after long term exposure to asbestos, fibres will accumulate in the lung if they are of the amphibole type, but will not if they are of the chrysotile type (Sébastien 1991). Short fibres have been shown to be cleared more rapidly than longer ones. Quartz is known to exhibit some lymph tropism and readily penetrates the lymphatic system. Modifying the surface chemistry of quartz particles has been shown to affect alveolar clearance (Hemenway et al. 1994; Dubois et al. 1988). Concomitant exposure to several dust types may also influence alveolar clearance (Davis, Jones and Miller 1991).

During alveolar clearance, dust particles may undergo some chemical and physical changes. Examples of theses changes include coating with ferruginous material, the leaching of some elemental constituents and the adsorption of some biological molecules.

Another notion recently derived from animal experiments is that of “lung overload” (Mermelstein et al. 1994). Rats heavily exposed by inhalation to a variety of insoluble dusts developed similar responses: chronic inflammation, increased numbers of particle-laden macrophages, increased numbers of particles in the interstitium, septal thickening, lipoproteinosis and fibrosis. These findings were not attributed to the reactivity of the dust tested (titanium dioxide, volcanic ash, fly ash, petroleum coke, polyvinyl chloride, toner, carbon black and diesel exhaust particulates), but to an excessive exposure of the lung. It is not known if lung overload must be considered in the case of human exposure to fibrogenic dusts.

Among the clearance pathways, the transfer towards the interstitium would be of particular importance for pneumoconioses. Clearance of particles having undergone sequestration into the interstitium is much less effective than clearance of particles engulfed by macrophages in the alveolar space and removed by ciliated airways (Vincent and Donaldson 1990). In humans, it was found that after long-term exposure to a variety of inorganic airborne contaminants, the storage was much greater in interstitial than alveolar macrophages (Sébastien et al. 1994). The view was also expressed that silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis involves the reaction of particles with interstitial rather than alveolar macrophages (Bowden, Hedgecock and Adamson 1989). Retention is responsible for the “dose”, a measure of the contact between the dust particles and their biological environment. A proper description of the dose would require that one know at each point in time the amount of dust stored in the several lung structures and cells, the physicochemical states of the particles (including the surface states), and the interactions between the particles and the pulmonary cells and fluids. Direct assessment of dose in humans is obviously an impossible task, even if methods were available to measure dust particles in several biological samples of pulmonary origin such as sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or tissue taken at biopsy or autopsy (Bignon, Sébastien and Bientz 1979). These methods were used for a variety of purposes: to provide information on retention mechanisms, to validate certain exposure information, to study the role of several dust types in pathogenic developments (e.g., amphiboles versus chrysotile exposure in asbestosis or quartz versus coal in CWP) and to assist in diagnosis.

But these direct measurements provide only a snapshot of retention at the time of sampling and do not allow the investigator to reconstitute dose data. New dosimetric models offer interesting perspectives in that regard (Katsnelson et al. 1994; Smith 1991; Vincent and Donaldson 1990). These models aim at assessing dose from exposure information by considering the probability of deposition and the kinetics of the different clearance pathways. Recently there was introduced into these models the interesting notion of “harmfulness delivery” (Vincent and Donaldson 1990). This notion takes into account the specific reactivity of the stored particles, each particle being considered as a source liberating some toxic entities into the pulmonary milieu. In the case of quartz particles for example, it could be hypothesized that some surface sites could be the source of active oxygen species. Models developed along such lines could also be refined to take into account the great interindividual variation generally observed with alveolar clearance. This was experimentally documented with asbestos, “high retainer animals” being at greater risk of developing asbestosis (Bégin and Sébastien 1989).

So far, these models were exclusively used by experimental pathologists. But they could also be useful to epidemiologists (Smith 1991). Most epidemiological studies looking at exposure response relationships relied on “cumulative exposure”, an exposure index obtained by integrating over time the estimated concentrations of airborne dust to which workers had been exposed (product of intensity and duration). The use of cumulative exposure has some limitations. Analyses based on this index implicitly assume that duration and intensity have equivalent effects on risk (Vacek and McDonald 1991).

Maybe the use of these sophisticated dosimetric models could provide some explanation for a common observation in the epidemiology of pneumoconioses: “the considerable between-work force differences” and this phenomenon was clearly observed for asbestosis (Becklake 1991) and for CWP (Attfield and Morring 1992). When relating the prevalence of the disease to the cumulative exposure, great differences—up to 50-fold—in risk were observed between some occupational groups. The geological origin of the coal (coal rank) provided partial explanation for CWP, mining deposits of high rank coal (a coal with high carbon content, like anthracite) yielding greater risk. The phenomenon remains to be explained in the case of asbestosis. Uncertainties on the proper exposure response curve have some bearings—at least theoretically—on the outcome, even at current exposure standards.

More generally, exposure metrics are essential in the process of risk assessment and the establishment of control limits. The use of the new dosimetric models may improve the process of risk assessment for pneumoconioses with the ultimate goal of increasing the degree of protection offered by control limits (Kriebel 1994).

Physicochemical Characteristics of Fibrogenic Dust Particles

A toxicity specific to each type of dust, related to the physicochemical characteristics of the particles (including the more subtle ones such as the surface characteristics), constitutes probably the most important notion to have emerged progressively during the last 20 years. In the very earliest stages of research, no differentiation were made among “mineral dusts”. Then generic categories were introduced: asbestos, coal, artificial inorganic fibres, phyllosilicates and silica. But this classification was found to be not precise enough to account for the variety in observed biological effects. Nowadays a mineralogical classification is used. For example, the several mineralogical types of asbestos are distinguished: serpentine chrysotile, amphibole amosite, amphibole crocidolite and amphibole tremolite. For silica, a distinction is generally made between quartz (by far the most prevalent), other crystalline polymorphs, and amorphous varieties. In the field of coal, high rank and low rank coals should be treated separately, since there is strong evidence that the risk of CWP and especially the risk of progressive massive fibrosis is much greater after exposure to dust produced in high rank coal mines.

But the mineralogical classification has also some limits. There is evidence, both experimental and epidemiological (taking into account “between-workforce differences”), that the intrinsic toxicity of a single mineralogical type of dust can be modulated by acting on the physicochemical characteristics of the particles. This raised the difficult question of the toxicological significance of each of the numerous parameters which can be used to describe a dust particle and a dust cloud. At the single particle level, several parameters can be considered: bulk chemistry, crystalline structure, shape, density, size, surface area, surface chemistry and surface charge. Dealing with dust clouds adds another level of complexity because of the distribution of these parameters (e.g., size distribution and the composition of mixed dust).

The size of the particles and their surface chemistry were the two parameters most studied to explain the modulation effect. As seen before, retention mechanisms are size related. But size may also modulate the toxicity in situ, as demonstrated by numerous animal and in vitro studies.

In the field of mineral fibres, the size was considered of so much importance that it constituted the basis of a pathogenesis theory. This theory attributed the toxicity of fibrous particles (natural and artificial) to the shape and size of the particles, leaving no role for the chemical composition. In dealing with fibres, size must be broken down into length and diameter. A two-dimensional matrix should be used to report size distributions, the useful ranges being 0.03 to 3.0mm for diameter and 0.3 to 300mm for length (Sébastien 1991). Integrating the results of the numerous studies, Lippman (1988) assigned a toxicity index to several cells of the matrix. There is a general tendency to believe that long and thin fibres are the most dangerous ones. Since the standards currently used in industrial hygiene are based upon the use of the optical microscope, they ignore the thinnest fibres. If assessing the specific toxicity of each cell within the matrix has some academic interest, its practical interest is limited by the fact that each type of fibre is associated with a specific size distribution that is relatively uniform. For compact particles, such as coal and silica, there is unclear evidence about a possible specific role for the different size sub-fractions of the particles deposited in the alveolar region of the lung.

More recent pathogenesis theories in the field of mineral dust imply active chemical sites (or functionalities) present at the surface of the particles. When the particle is “born” by separation from its parent material, some chemical bonds are broken in either a heterolytic or a homolytic way. What occurs during breaking and subsequent recombinations or reactions with ambient air molecules or biological molecules makes up the surface chemistry of the particles. Regarding quartz particles for example, several chemical functionalities of special interest have been described: siloxane bridges, silanol groups, partially ionized groups and silicon-based radicals.

These functionalities can initiate both acid-base and redox reactions. Only recently has attention been drawn to the latter (Dalal, Shi and Vallyathan 1990; Fubini et al. 1990; Pézerat et al. 1989; Kamp et al. 1992; Kennedy et al. 1989; Bronwyn, Razzaboni and Bolsaitis 1990). There is now good evidence that particles with surface-based radicals can produce reactive oxygen species, even in a cellular milieu. It is not certain if all the production of oxygen species should be attributed to the surface-based radicals. It is speculated that these sites may trigger the activation of lung cells (Hemenway et al. 1994). Other sites may be involved in the membranolytic activity of the cytotoxic particles with reactions such as ionic attraction, hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic bonding (Nolan et al. 1981; Heppleston 1991).

Following the recognition of surface chemistry as an important determinant of dust toxicity, several attempts were made to modify the natural surfaces of mineral dust particles to reduce their toxicity, as assessed in experimental models.

Adsorption of aluminium on quartz particles was found to reduce their fibrogenicity and to favour alveolar clearance (Dubois et al. 1988). Treatment with polyvinylpyridine-N-oxide (PVPNO) had also some prophylactic effect (Goldstein and Rendall 1987; Heppleston 1991). Several other modifying processes were used: grinding, thermal treatment, acid etching and adsorption of organic molecules (Wiessner et al. 1990). Freshly fractured quartz particles exhibited the highest surface activity (Kuhn and Demers 1992; Vallyathan et al. 1988). Interestingly enough, every departure from this “fundamental surface” led to a decrease in quartz toxicity (Sébastien 1990). The surface purity of several naturally occurring quartz varieties could be responsible for some observed differences in toxicity (Wallace et al. 1994). Some data support the idea that the amount of uncontaminated quartz surface is an important parameter (Kriegseis, Scharman and Serafin 1987).

The multiplicity of the parameters, together with their distribution in the dust cloud, yields a variety of possible ways to report air concentrations: mass concentration, number concentration, surface area concentration and concentration in various size categories. Thus, numerous indices of exposure can be constructed and the toxicological significance of each has to be assessed. The current standards in occupational hygiene reflect this multiplicity. For asbestos, the standards are based on the numerical concentration of fibrous particles in a certain geometrical size category. For silica and coal, the standards are based on the mass concentration of respirable particles. Some standards have also been developed for exposure to mixtures of particles containing quartz. No standard is based upon surface characteristics.

Biological Mechanisms Inducing the Fundamental Lesions

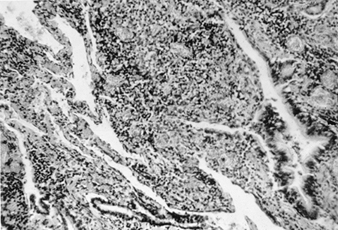

Pneumoconioses are interstitial fibrous lung diseases, the fibrosis being diffuse or nodular. The fibrotic reaction involves the activation of the lung fibroblast (Goldstein and Fine 1986) and the production and metabolism of the connective tissue components (collagen, elastin and glycosaminoglycans). It is considered to represent a late healing stage after lung injury (Niewoehner and Hoidal 1982). Even if several factors, essentially related to the characteristics of exposure, can modulate the pathological response, it is interesting to note that each type of pneumoconiosis is characterized by what could be called a fundamental lesion. The fibrosing alveolitis around the peripheral airways constitutes the fundamental lesion of asbestos exposure (Bégin et al. 1992). The silicotic nodule is the fundamental lesion of silicosis (Ziskind, Jones and Weil 1976). Simple CWP is composed of dust macules and nodules (Seaton 1983).

The pathogenesis of the pneumoconioses is generally presented as a cascade of events whose sequence runs as follows: alveolar macrophage alveolitis, signalling by inflammatory cell cytokines, oxidative damage, proliferation and activation of fibroblasts and the metabolism of collagen and elastin. Alveolar macrophage alveolitis is a characteristic reaction to retention of fibrosing mineral dust (Rom 1991). The alveolitis is defined by increased numbers of activated alveolar macrophages releasing excessive quantities of mediators including oxidants, chemotaxins, fibroblast growth factors and protease. Chemotaxins attract neutrophils and, together with macrophages, may release oxidants capable of injuring alveolar epithelial cells. Fibroblast growth factors gain access to the interstitium, where they signal fibroblasts to replicate and increase the production of collagen.

The cascade starts at the first encounter of particles deposited in the alveoli. With asbestos for example, the initial lung injury occurs almost immediately after exposure at the alveolar duct bifurcations. After only 1 hour of exposure in animal experiments, there is active uptake of fibres by type I epithelial cells (Brody et al. 1981). Within 48 hours, increased numbers of alveolar macrophages accumulate at sites of deposition. With chronic exposure, this process may lead to peribronchiolar fibrosing alveolitis.

The exact mechanism by which deposited particles produce primary biochemical injury to the alveolar lining, a specific cell, or any of its organelles, is unknown. It may be that extremely rapid and complex biochemical reactions result in free radical formation, lipid peroxidation, or a depletion in some species of vital cell protectant molecule. It has been shown that mineral particles can act as catalytic substrates for hydroxyl and superoxide radical generation (Guilianelli et al. 1993).

At the cellular level, there is slightly more information. After deposition at the alveolar level, the very thin epithelial type I cell is readily damaged (Adamson, Young and Bowden 1988). Macrophages and other inflammatory cells are attracted to the damage site and the inflammatory response is amplified by the release of arachidonic acid metabolites such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes together with exposure of the basement membrane (Holtzman 1991; Kuhn et al. 1990; Engelen et al. 1989). At this stage of primary damage, the lung architecture becomes disorganized, showing an interstitial oedema.

During the chronic inflammatory process, both the surface of the dust particles and the activated inflammatory cells release increased amounts of reactive oxygen species in the lower respiratory tract. The oxidative stress in the lung has some detectable effects on the antioxidant defense system (Heffner and Repine 1989), with expression of antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidases and catalase (Engelen et al. 1990). These factors are located in the lung tissue, the interstitial fluid and the circulating erythrocytes. The profiles of antioxidant enzymes may depend on the type of fibrogenic dust (Janssen et al. 1992). Free radicals are known mediators of tissue injury and disease (Kehrer 1993).

Interstitial fibrosis does result from a repair process. There are numerous theories to explain how the repair process takes place. The macrophage/fibroblast interaction has received the greatest attention. Activated macrophages secrete a network of proinflammatory fibrogenic cytokines: TNF, IL-1, transforming growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor. They also produce fibronectin, a cell surface glycoprotein which acts as a chemical attractant and, under some conditions, as a growth stimulant for mesenchymal cells. Some authors consider that some factors are more important than others. For example, special importance was ascribed to TNF in the pathogenesis of silicosis. In experimental animals, it was shown that collagen deposition after silica instillation in mice was almost completely prevented by anti-TNF antibody (Piguet et al. 1990). The release of platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor was presented as playing an important role in the pathogenesis of asbestosis (Brody 1993).

Unfortunately, many of the macrophage/fibroblast theories tend to ignore the potential balance between the fibrogenic cytokines and their inhibitors (Kelley 1990). In fact, the resulting imbalance between oxidizing and antioxidizing agents, proteases and antiproteases, the arachidonic acid metabolites, elastases and collagenases, as well as the imbalances between the various cytokines and growth factors, would determine the abnormal remodelling of the interstitium component towards the several forms of pneumoconioses (Porcher et al. 1993). In pneumoconioses, the balance is clearly directed towards an overwhelming effect of the damaging cytokine activities.

Because type I cells are incapable of division, after the primary insult, the epithelial barrier is replaced with type II cells (Lesur et al. 1992). There is some indication that if this epithelial repair process is successful and that the regenerating type II cells are not damaged further, the fibrogenesis is not likely to proceed. Under some conditions, the repair by the type II cell is taken to excess, resulting in alveolar proteinosis. This process was clearly demonstrated after silica exposure (Heppleston 1991). To what extent the alterations in epithelial cells influence the fibroblasts is uncertain. Thus, it would seem that fibrogenesis is initiated in areas of extensive epithelial damage, as fibroblasts replicate, then differentiate and produce more collagen, fibronectin and other components of the extracelluar matrix.

There is abundant literature on the biochemistry of the several types of collagen formed in pneumoconioses (Richards, Masek and Brown 1991). The metabolism of such collagen and its stability in the lung are important elements of the fibrogenesis process. The same probably holds for the other components of the damaged connective tissue. The metabolism of collagen and elastin is of particular interest in the healing phase since these proteins are so important to lung structure and function. It has been very nicely shown that alterations in the synthesis of these proteins might determine whether emphysema or fibrosis evolves after lung injury (Niewoehner and Hoidal 1982). In the disease state, mechanisms such as an increase in transglutaminase activity could favour the formation of stable protein masses. In some CWP fibrotic lesions, the protein components account for one-third of the lesion, the rest being dust and calcium phosphate.

Considering only collagen metabolism, several stages of fibrosis are possible, some of which are potentially reversible while others are progressive. There is experimental evidence that unless a critical exposure is exceeded, the early lesions can regress and irreversible fibrosis is an unlikely outcome. In asbestosis for example, several types of lung reactions were described (Bégin, Cantin and Massé 1989): a transient inflammatory reaction without lesion, a low retention reaction with fibrotic scar limited to the distal airways, a high inflammatory reaction sustained by the continuous exposure and the weak clearance of the longest fibres.

It can be concluded from these studies that exposure to fibrotic dust particles is able to trigger several complex biochemical and cellular pathways involved in lung injury and repair. Exposure regimen, physicochemical characteristics of the dust particles, and possibly individual susceptibility factors seem to be the determinants of the fine balance among the several pathways. Physicochemical characteristics will determine the type of the ultimate fundamental lesion. Exposure regimen seems to determine the time course of events. There is some indication that sufficiently low exposure regimens can in most cases limit the lung reaction to non-progressive lesions with no disability or impairment.

Medical surveillance and screening always have been part of the strategies for the prevention of pneumoconioses. In that context, the possibility of detecting some early lesions is advantageous. Increased knowledge of pathogenesis paved the way to the development of several biomarkers (Borm 1994) and to the refinement and use of “non-classical” pulmonary investigation techniques such as the measurement of the clearance rate of deposited 99 technetium diethylenetriamine-penta-acetate (99 Tc-DTPA) to assess pulmonary epithelial integrity (O’Brodovich and Coates 1987), and quantitative gallium-67 lung scan to assess inflammatory activity (Bisson, Lamoureux and Bégin 1987).