Physical training and fitness programs are generally the most frequently encountered element in worksite health promotion and protection programs. They are successful when they contribute to the goals of the organization, promote the health of employees, and remain pleasing and useful to those participating (Dishman 1988). Because organizations around the world have widely diverse goals, workforces and resources, physical training and fitness programs vary greatly in how they are organized and in what services they provide.

This article is concerned with the reasons for which organizations offer physical training and fitness programs, how such programs fit within an administrative structure, the typical services offered to participants, the specialized personnel who offer these services, and the issues most often involved in worksite fitness programming, including the needs of special populations within the workforce. It will focus primarily on programs conducted onsite in the workplace.

Quality and Fitness Programming

Today’s global economy shapes the goals and business strategies of tens of thousands of employers and affects millions of workers around the world. Intense international competition requires organizations to offer products and services of higher value at ever lower costs, that is, to pursue so-called “quality” as a goal. Quality-driven organizations expect workers to be “customer oriented,” to work energetically, enthusiastically and accurately throughout the entire day, to continually train and improve themselves professionally and personally, and to take responsibility for both their workplace behavior and their personal well-being.

Physical training and fitness programs can play a role in quality-driven organizations by helping workers to achieve a high level of “wellness”. This is particularly important in “white-collar” industries, where employees are sedentary. In manufacturing and heavier industries, strength and flexibility training can enhance work capacity and endurance and protect workers from occupational injuries. In addition to physical improvement, fitness activities offer relief from stress and carry a personal sense of responsibility for health into other aspects of lifestyle such as nutrition and weight control, avoidance of alcohol and drug abuse, and smoking cessation.

Aerobic conditioning, relaxation and stretching exercises, strength training, adventure and challenge opportunities and sports competitions are typically offered in quality-driven organizations. These offerings are often structured within the organization’s wellness initiatives—“wellness” involves helping people to actualize their full potential while leading a lifestyle that promotes health—and they are based on the awareness that, since sedentary living is a well-demonstrated risk factor, regular exercise is an important habit to foster.

Basic Fitness Services

Participants in fitness programs should be instructed in the rudiments of fitness training. The instruction includes the following components:

- a minimum number of exercise sessions per week to achieve fitness and good health (three or four times a week for 30 to 60 minutes per session)

- learning how to warm up, exercise and cool down

- learning how to monitor heart rate and how to safely raise one’s heart rate to a training level appropriate for one’s age and fitness level

- graduating training from light to heavy to ultimately achieve a high level of fitness

- techniques for cross training

- The principles of strength training, including resistance and overload, and combining repetitions and sets to achieve strengthening goals

- strategic rest and safe lifting techniques

- relaxation and stretching as an integral part of a total fitness programme

- learning how to customize workouts to suit one’s personal interests and lifestyle

- achieving an awareness of the role that nutrition plays in fitness and overall good health.

Besides instruction, fitness services include fitness assessment and exercise prescription, orientation to the facility and training in the use of the equipment, structured aerobic classes and activities, relaxation and stretching classes, and back-pain prevention classes. Some organizations offer one-on-one training, but this can be quite expensive since it is so staff-intensive.

Some programs offer special “work hardening” or “conditioning,” that is, training to enhance workers’ capacities to perform repetitive or rigorous tasks and to rehabilitate those recovering from injuries and illnesses. They often feature work breaks for special exercises to relax and stretch overused muscles and strengthen antagonistic sets of muscles to prevent overuse and repetitive injury syndromes. When advisable, they include suggestions for modifying the job content and/or the equipment used.

Physical Training and Fitness Personnel

Exercise physiologists, physical educators, and recreational specialists make up the majority of the professionals working in worksite physical fitness programs. Health educators and rehabilitation specialists also participate in these programs.

The exercise physiologist designs personalized exercise regimens for individuals based on a fitness assessment which generally includes a health history, a health risk screening, assessment of fitness levels and exercise capacity (essential for those with handicaps or recovering from injury), and confirmation of their fitness goals. The fitness assessment includes the determination of resting heart rate and blood pressure, body composition. muscle strength and flexibility, cardiovascular efficiency and, often, blood lipid profiles. Typically, the findings are compared with norms for people of the same sex and age.

None of the services offered by the physiologist are meant to diagnose disease; employees are referred to the employee health service or their personal physicians when abnormalities are found. In fact, many organizations require that a prospective applicant obtain clearance from a physician before joining the program. In the case of employees recovering from injuries or illness, the physiologist will work closely with their personal physicians and rehabilitation counselors.

Physical educators have been trained to lead exercise sessions, to teach the principles of healthy and safe exercise, to demonstrate and coach various athletic skills, and to organize and administer a multifaceted fitness program. Many have been trained to perform fitness assessments although, in this age of specialization, that task is performed more often by the exercise physiologist.

Recreational specialists carry out surveys of participants’ needs and interests to determine their lifestyles and their recreational requirements and preferences. They may conduct exercise classes but generally focus on arranging trips, contests and activities that instruct, physically challenge and motivate participants to engage in wholesome physical activity.

Verifying the training and competence of physical training and fitness personnel often presents problems to organizations seeking to staff a program. In the United States, Japan and many other countries, government agencies require academic credentials and supervised experience of physical educators who teach in school systems. Most governments do not require certification of exercise professionals; for example, in the United States, Wisconsin is the only state that has enacted legislation dealing with fitness instructors. In considering an involvement with health clubs in the community, whether voluntary like the YMCAs or commercial, special caution should be taken to verify the competence of the trainers they provide since many are staffed by volunteers or poorly trained individuals.

A number of professional associations offer certification for those working in the adult fitness field. For example, the American College of Sports Medicine offers a certificate for exercise instructors and the International Dance Education Association offers a certificate for aerobics instructors. These certificates, however, represent indicators of experience and advanced training rather than licenses to practice.

Fitness Programs and the Organization’s Structure

As a rule, only medium-sized to large-sized organizations (500 to 700 employees is generally considered the minimum) can undertake the task of providing physical training facilities for their employees at the worksite. Major considerations other than size include the ability and willingness to make the necessary budgetary allocations and availability of space to house the facility and whatever equipment it may require, including dressing and shower rooms.

Administrative placement of the program within the organization usually reflects the goals set for it. For example, if the goals are primarily health-related (e.g., cardiovascular risk reduction, reducing illness absences, prevention and rehabilitation of injuries, or contributing to stress management) the program will usually be found in the medical department or as a supplement to the employee health service. When the primary goals relate to employee morale and recreation, it will usually be found in the human resources or employee relations department. Since human resources departments are usually charged with implementing quality improvement programs, fitness programs with a wellness and quality focus will often be located there.

Training departments rarely are assigned responsibility for physical training and fitness programs since their mission is usually limited to specific skill development and job training. However, some training departments offer outdoor adventure and challenge opportunities to employees as ways to create a sense of teamwork, build self-confidence and explore ways to overcome adversity. When jobs involve physical activity, the training program may be responsible for teaching proper work techniques. Such training units will often be found in police, fire and rescue organizations, trucking and delivery firms, mining operations, oil exploration and drilling companies, diving and salvage organizations, construction firms, and the like.

Onsite or Community-based Fitness Programs

When space and economic considerations do not allow comprehensive exercise facilities, limited programs may still be conducted in the workplace. When not in use for their designed purposes, lunch and meeting rooms, lobbies and parking areas may be used for exercise classes. One New York City-based insurance company created an indoor jogging track in a large storage area by arranging a path between banks of filing cabinets containing important but infrequently consulted documents. In many organizations around the world, work breaks are regularly scheduled during which employees stand at their work stations and do calisthenics and other simple exercises.

When onsite fitness facilities are not feasible (or when they are too small to accommodate all the employees who would use them), organizations turn to community-based settings such as commercial health clubs, schools and colleges, churches, community centers, clubs and YMCAs, town- or union-sponsored recreation centers, and so on. Some industrial parks house an exercise facility shared by the corporate tenants.

On another level, fitness programs may consist of uncomplicated physical activities practiced in or about the home. Recent research has established that even low to moderate levels of daily activity may have protective health effects. Activities like recreational walking, biking or stair-climbing which require the person to dynamically exercise large muscle groups for 30 minutes five times a week, may prevent or delay the advance of cardiovascular disease while providing a pleasant respite from daily stress. Programs that encourage walking and bicycling to work can be developed for even very small companies and they cost very little to implement.

In some countries, workers are entitled to leaves that may be spent at spas or health resorts which offer a comprehensive program of rest, relaxation, exercise, healthful diet, massage and other forms of restorative therapy. The aim, of course, is to have them maintain such a healthful lifestyle after they return to their homes and jobs.

Exercise for Special Populations

Older workers, the obese and especially those who have been sedentary for long can be offered low-impact and low-intensity exercise programs in order to avert orthopedic injuries and cardiovascular emergencies. In onsite facilities, special times or separate workout spaces may be arranged to protect the privacy and dignity of these populations.

Pregnant women who have been physically active may continue to work or exercise with the advice and consent of their personal physicians, keeping in mind the medical guidelines concerning exercise during pregnancy (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 1994). Some organizations offer special reconditioning exercise programs for women returning to work after delivery.

Physically challenged or handicapped workers should be invited to participate in the fitness program both as a matter of equity and because they may accrue even greater benefits from the exercise. Program staff, however, should be alert to conditions that may entail greater risk of injury or even death, such as Marfan’s syndrome (a congenital disorder) or certain forms of heart disease. For such individuals, preliminary medical evaluation and fitness assessment is particularly important, as is careful monitoring while exercising.

Setting Goals for the Exercise Program

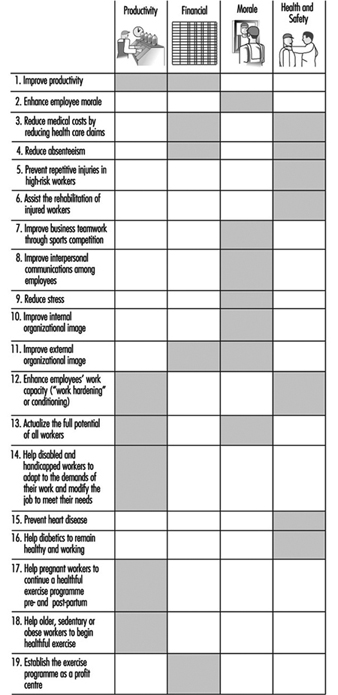

The goals selected for an exercise program should complement and support those of the organization. Figure 1 presents a checklist of potential program goals which, when ranked in order of importance to a particular organization and aggregated, will help in shaping the program.

Figure 1. Suggested organizational goals for a fitness and exercise programme.

Eligibility for the Exercise Program

Since the demand may exceed both the program’s budget allocation and the available space and time, organizations have to carefully consider who should be eligible to participate. It is prudent to know in advance why this benefit is being offered and how many employees are likely to take advantage of it. Lack of preparation in this regard may lead to embarrassment and ill will when those who desire to exercise cannot be accommodated.

Particularly when providing an onsite facility, some organizations limit eligibility to managers above a certain level in the organization chart. They rationalize this by arguing that, since such individuals are paid more, their time is more valuable and it is proper to give them priority of access. The program then becomes a special privilege, like the executive dining room or a conveniently located parking space. Other organizations are more even-handed and offer the program to all on a first-come, first-served basis. Where demand exceeds the facility’s capacity, some use length of service as a criterion of priority. Rules setting minimum monthly use are sometimes used to help manage the space problem by discouraging the casual or episodic participant from continuing as a member.

Recruiting and Retaining Program Participants

One problem is that the convenience and low cost of the facility may make it particularly attractive to those already committed to exercise, who may leave little room for those who may need it much more. Most of the former will probably continue to exercise anyway while many of the latter will be discouraged by difficulties or delays in entering the program. Accordingly, an important adjunct to recruiting participants is simplifying and facilitating the enrolment process.

Active efforts to attract participants are usually necessary, at least when the program is initiated. They include in-house publicity via posters, flyers and announcements in available intramural communications media, as well as open visits to the exercise facility and the offer of experimental or trial memberships.

The problem of dropout is an important challenge to program administrators. Employees cite boredom with exercise, muscular aches and pains induced by exercise, and time pressure as the major reasons for dropping out. To counter this, facilities entertain members with music, videotapes and television programs, motivational games, special events, awards such as T-shirts and other gifts and certificates for attendance or reaching individual fitness goals. Properly designed and supervised exercise regimens will minimize injuries and aches and pains and, at the same time, make the sessions efficient and less time-consuming. Some facilities offer newspapers and business publications as well as business and training programs on television and videotape to be accessed while exercising to help justify the time spent in the facility.

Safety and Supervision

Organizations offering worksite fitness programs must do so in a safe manner. Potential members must be screened for medical conditions that might be affected adversely by exercise. Only well-designed and well-maintained equipment should be available and participants must be properly instructed in its use. Safety signs and rules on the appropriate use of the facility should be posted and enforced, and all staff should be trained in emergency procedures, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation. A trained exercise professional should oversee the operation of the facility.

Record Keeping and Confidentiality

Individual records containing information about health and physical status, fitness assessment and exercise prescription, fitness goals and progress toward their accomplishment and any relevant notes should be maintained. In many programs, the participant is allowed to chart for himself or herself what was done on each visit. At a minimum, the content of records should be kept secure from all but the individual participant and members of the program staff. Except for the staff of the employee health service, who are bound to the same rules of confidentiality and, in an emergency, the participant’s personal physician, details of the individual’s participation and progress should not be revealed to anyone without the individual’s express consent.

Program staff may be required to make periodic reports to management presenting aggregate data regarding participation in the program and the results.

Whose Time, Who Pays?

Since most worksite exercise programs are voluntary and established to benefit the worker, they are considered an extra benefit or privilege. Accordingly, the organization traditionally offers the program on the worker’s own time (during lunch time or after hours) and he or she is expected to pay all or part of the cost. This is generally applicable also to programs provided offsite in community facilities. In some organizations, the employees’ contributions are indexed to salary level and some offer “scholarships” to those who are low paid or those with financial problems.

Many employers allow participation during working hours, usually for higher-level employees, and pick up most if not all of the cost. Some refund employees’ contributions if certain attendance or fitness goals are attained.

When program participation is mandatory, as in training to prevent potential work injuries or to condition workers to perform certain tasks, government regulations and/or labor union agreements require it to be provided during work hours with all costs borne by the employer.

Managing Participants’ Aches and Pains

Many people believe that exercise must be painful in order to be beneficial. This is frequently expressed by the motto “No pain, no gain”. It is incumbent on the program staff to counter this erroneous belief by changing the perception of exercise through awareness campaigns and educational sessions and by ensuring that the intensity of the exercises is graduated so that they remain pain-free and enjoyable while still improving the participant’s level of fitness.

If participants complain of aches and pains, they should be encouraged to continue to exercise at a lower level of intensity or simply to rest until healed. They should be taught “RICE,” the acronym for the principles of treating sports injuries: Rest; Ice down the injury; Compress any swelling; and Elevate the injured body part.

Sports Programs

Many organizations encourage employees to participate in company-sponsored athletic events. These may range from softball or football games at the yearly company picnic, to intramural league play in a variety of sports, to inter-company competitions such as the Chemical Bank’s Corporate Challenge, a competitive distance run for teams of employees from participating organizations that originated in New York City and now has spread to other areas, with many more corporations joining as sponsors.

The key concept for sports programs is risk management. While the gains from competitive sports can be considerable, including better morale and stronger “team” feelings, they inevitably entail some risks. When workers engage in competition, they may bring to the game work-related psychological “baggage” that can cause problems, particularly if they are not in good physical condition. Examples include the middle-aged, out-of-shape manager who, seeking to impress younger subordinates, may be injured by exceeding his or her physical capabilities, and the worker who, feeling challenged by another in competing for status in the organization, may convert what is meant to be a friendly game into a dangerous, bruising mêlée.

The organization wishing to offer involvement in competitive sports should seriously consider the following advice:

- Be sure that participants understand the purpose of the event and remind them that they are employees of the organization and not professional athletes.

- Establish firm rules and guidelines governing safe and fair play.

- Although signed informed consent and waiver forms do not always protect the organization from liability in the event of injury, they help participants to comprehend the extent of the risk associated with the sport.

- Offer conditioning clinics and practice sessions prior to the opening of the competition so that participants can be in good physical shape when they begin to play.

- Require, or at least encourage, a complete physical examination by the employee’s personal physician if not available in the employee health service. (Note: the organization may have to accept financial responsibility for this.)

- Perform a safety inspection of the athletic field and all of the sports equipment. Provide or require personal protective equipment such as helmets, clothing, safety pads and goggles.

- Make sure that referees and security personnel as needed are on hand for the event.

- Have first aid supplies on hand and a pre-arranged plan for emergency medical care and evacuation if needed.

- Be sure that the organization’s liability and disability insurance coverage covers such events and that it is adequate and in force. (Note: it should cover employees and others who attend as spectators as well as those on the team.)

For some companies, sports competition is a major source of employee disability. The above recommendations indicate that the risk may be “managed,” but serious thought should be given to the net contribution that sports activities can reasonably be expected to provide to the physical fitness and training program.

Conclusion

Well-designed, professionally managed workplace exercise programs benefit employees by enhancing their health, well-being, morale and work performance. They benefit organizations by improving productivity qualitatively and quantitatively, preventing work-related injuries, accelerating employees’ recovery from illness and injury, and reducing absenteeism. The design and implementation of each program should be individualized in accord with the characteristics of the organization and its workforce, with the community in which it operates, and with the resources that can be made available for it. It should be managed or at least supervised by a qualified fitness professional who will consistently be mindful of what the program contributes to its participants and to the organization and who will be ready to modify it as new needs and challenges arise.