Stationary routing machines are used in general for the manufacture of wood articles and furniture elements, but sometimes also for machining plastics and light alloys. Important types of routing machines are copy routers, pattern millers, machines with mobile router heads and automatic copying machines. The automatic copying machines are generally used for machining several workpieces simultaneously.

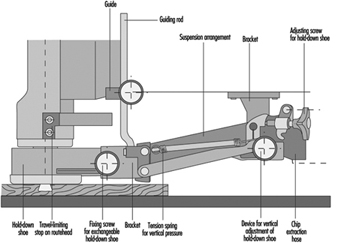

A common feature of all routing machines is that the tool is located above the workpiece support, which is normally a table. The tool-spindle axis is nearly always vertical, but on some machines the router head, and thus also the tool-spindle axis, may be tilted. The machining head is lowered for machining and returns automatically to its initial (rest) position. On older machines the machining head is lowered manually by operating a mechanical foot-pedal or hand lever. On modern machines the head is generally lowered by a pneumatic or hydraulic system. Figure 1 shows various accessories (hold-down shoes, guides and so on) and the Swiss National Accident Insurance Organization (SUVA) safety guard.

Figure 1. SUVA safety device with routing tool in working position

The tool-spindle is driven either by a belt drive or directly by a high-frequency motor, which is often of the two-speed type. The tool-spindle speeds generally range from 6,000 to 24,000 rpm. They are lower in pattern millers, where the lowest speed may be 250 rpm. Pattern millers are often equipped with a gearbox for the selection of different speeds.

The cutting diameter of the routing tool varies from 3 to 50 mm. However, on special pattern millers the cutting diameter of the tool may be as large as 300 mm.

Tooling

On routing machines single-edged spoon bits, double-edged panel cutters or solid-shaped cutters mainly are used. Like any tool they must be designed and made of such materials that will withstand the forces and loads to be expected during operation. Machines should be used and maintained in compliance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

The routing tools should be:

- clearly and permanently marked with the permissible speed, e.g., less than 20,000 rpm

- of a type tested by an approved body

- of round form design with a minimal radial cutting edge projection to reduce the danger of kickback.

Guarding of the tool

On routing machines where the tool is moving and the workpiece remains fixed, access to the rotating tool should be prevented by an adjustable guard (hand protector). It should be supplemented by a movable guard which can be lowered on to the workpiece surface. The lower end of this movable guard may be a brush.

On routing machines where the workpiece is held and/or fed by hand, it is highly recommended to use a safety device exerting vertical pressure on the workpiece. The SUVA has designed such a guard. This safety device has been successfully used since the end of the 1940s and is still the most complete guard of its kind. Its main features are:

- prevention of unintentional contact with the rotating tool both in its rest position and in its working position

- fast and easy changeover from one size of hold-down shoe to another. Several sizes of hold-down shoes are available to fit tools with different cutting diameters

- manually adjustable amount of pressure exerted on the workpiece by the hold-down shoe

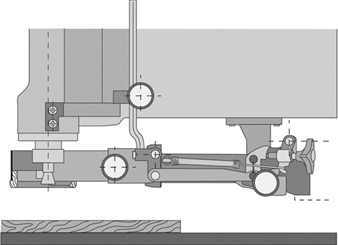

- automatic return of the hold-down shoe to its upper position when the router head rises to its rest position. The guarding device can be adjusted so that the hold-down shoe may be lifted only when the lower edge of the tool is above the level of the lower edge of the hold-down shoe; this is to prevent any unintentional contact with the tool from below (see figure 2. Serious injuries to the back of the hand, where the tendons are protected only by the skin, are thus avoided.

Figure 2. Safety device with routing tool in initial position

- possibility of connection of a chip extraction system to the guarding device.

This guarding device also enables workpieces to be routed along a guide with the aid of a horizontal pressure pad.

Hazards

Routing machines have been found to be less dangerous than vertical spindle moulding machines. One reason for this is the smaller diameter of most routing tools. However, the tools on routing machines are easily accessible and thus present a constant hazard for the hands and arms of the operator. Therefore, copy routers, where the workpiece is generally fed by hand, are by far the most dangerous routing machines.

Causes of accidents

The main causes of router accidents are:

- unintentional contact of the hand or arm with the rotating tool in its rest position (1) when removing chips and dust from the table by hand rather than using a wooden stick, (2) when the workpiece or the jig is not correctly handled or (3) when the sleeve of the operator’s clothing becomes entangled in the rotating tool

- unintentional contact of the hand with the routing tool as a result of kickback of the workpiece held by hand.

Kickback may happen because of:

- an unsafe working practice

- faults in the workpiece (knots, etc.)

- workpieces being fed into the tool too abruptly or from the wrong direction

- blunt cutter edges

- inadequate cutting speed

- incorrect fixing of the workpiece to the jig

- workpiece breakage

- ejection of the tool or parts of the tool due to bad tool design, excessive hardness of the tool material, faults in the material of the tool, overspeed of the tool or poor clamping of the tool in the tool holder.

In the event of ejection of a tool or workpiece, not only the operator but also other persons working in the area may be injured by ejected parts.

Measures to prevent accidents

Measures to prevent accidents should be directed at:

- the design and construction of the machine

- the tooling

- guarding the tool in its rest position (figure 15) and as far as possible in the working position (figure 14), in particular when the workpiece is held and fed by hand.

Design and Construction of the Machine

Routing machines must be designed to be safe to operate. It should be ensured that:

- the machine is sufficiently rigid

- the electrical equipment conforms to safety regulations

- actuators used to initiate a start function or movement of a machine element are constructed and mounted so as to minimize inadvertent operation

- access to moving machine parts, such as belt drives, hydraulic or pneumatically moved router heads or travelling tables on machines with automatic feeds, are prevented by adequate guarding

- the actual revolutions per minute of the tool are clearly visible to the operator

- the safety devices and chip extraction systems are easy to install

- the noise level of the machine is reduced as far as possible.

Furthermore, it is advisable to equip the tool drive of the routing machine with an automatic brake that activates when the machine is stopped. The braking time should not exceed 10 seconds.

Sample checklist

Housekeeping

1. A daily housekeeping programme is essential.

2. Dust accumulations of 1/8” depth in any area indicate a need for cleaning. It should be noted that any accumulation of dust may lead to a fire. The finer the dust, the greater the hazards.

3. Clean wood dust frequently.

a. Wipe down daily around hot surfaces.

b. Major blow down or vacuum when possible of all areas, including rafters, at least twice per year.

c. When concentrations are high, work small areas at a time.

d. Low humidity increases the potential for hazards and should be taken in consideration during blow downs.

4. Schedule blow downs or clean ups while equipment is down, such as Friday afternoons and weekends.

Electrical maintenance

1. Inspect/clean all motors regularly to avoid dust build-up.

2. Ensure all electrical boxes and panels meet the National Electrical Code requirements for their classified location.

3. Listen for unusual sounds, note unusual smells and watch for visual dust accumulations on machines and motors. Check motors and other electricals often to detect overheating.

4. Ensure that maintenance or operating personnel are lubricating bearings to motors, conveyors, chains and sprockets on a timely basis.

5. Ensure that electrical panels and boxes are kept closed and maintained to prevent dust accumulations, including keeping all knockout holes plugged.

Fire prevention

1. Actively prohibit smoking in unauthorized locations.

2. Adopt procedures for hot-work permits and ensure that procedures are followed.

3. Do not allow operator-controlled machines to operate unattended.

4. Install a device at the mouth of the dust collecting system to prevent sanding belts and other spark producing items from entering the system and causing a fire.

5. Trap metal in wood hogs by installing magnets in the conveyor system and metal detectors in the hog. Policies and procedures should be implemented to prevent metal and other foreign objects from reaching the hogs.

6. Conduct weekly and monthly inspections of fire protective systems including fire extinguishers, fire hoses, alarms and sprinkler control valves.

7. Ensure that boiler rooms and heating equipment are free of dust accumulations, that written boiler start-up procedures are being followed and that properly classified equipment is used.

8. Recognize the correct procedure in fighting dust fires.

9. Request a detailed inspection by the local fire marshal or insurance carrier.

10. Encourage mock drills/visits by the local fire department.

11. Install spark detection and extinguishing systems in dust collection systems and check periodically to ensure that they are working.

12. Review evacuation plans, emergency lighting, fire drills periodically for each work shift.

Miscellaneous

1. Contact insurance carrier for assistance in hazard identifications associated with safety, health and fire prevention.

2. Contact appropriate government safety agencies for additional assistance.

3. Employees should enter dust silos only when confined space procedures are followed.

4. All operators should ensure that dust collecting systems are working properly and report any malfunctions to management immediately.

5. Check for objects obstructing the ducts to the dust system.

6. It is recommended that all supervisors, safety committee members and other employees be made aware of the contents of this voluntary checklist to achieve maximum implementation.