Rolling Mills

Adapted from 3rd edition, Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety.

Acknowledgements: The description of hot- and cold-rolling mill operations is used with permission of the American Iron and Steel Institute.

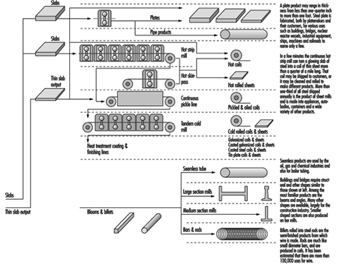

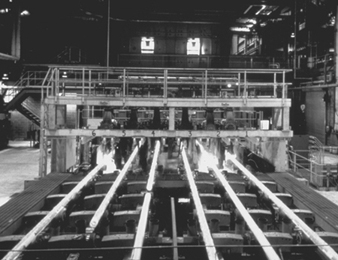

Hot slabs of steel are converted into long coils of thin sheets in continuous hot strip mills. These coils may be shipped to customers or may be cleaned and cold rolled to make products. See figure 1 for a flow line of the processes.

Figure 1. Flow line of hot- & cold-rolled sheet mill products

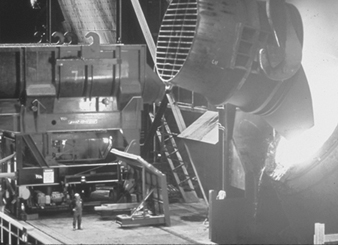

Continuous Hot Rolling

A continuous hot-rolling mill may have a conveyor that is several thousand feet long. The steel slab exits from a slab reheating furnace onto the beginning of the conveyor. Surface scale is removed from the heated slab, which then becomes thinner and longer as it is squeezed by horizontal rolls at each mill, usually called roughing stands. Vertical rolls at the edges help control width. The steel next enters the finishing stands for final reduction, travelling at speeds up to 80 kilometres per hour as it crosses the cooling table and is coiled.

The hot-rolled sheet steel is normally cleaned or pickled in a bath of sulphuric or hydrochloric acid to remove surface oxide (scale) formed during hot rolling. A modern pickler operates continuously. When one coil of steel is almost cleaned, its end is sheared square and welded to the start of a new coil. In the pickler, a temper mill helps break up the scale before the sheet enters the pickling or cleaning section of the line.

An accumulator is located beneath the rubber-lined pickling tanks, the rinsers and the dryers. The sheet accumulated in this system feeds into the pickling tanks when the entry-end of the line is stopped to weld on a new coil. Thus it is possible to clean a sheet continuously at the rate of 360 m (1,200 feet) per minute. A smaller looping system at the delivery end of the line permits continuous line operation during interruptions for coiling.

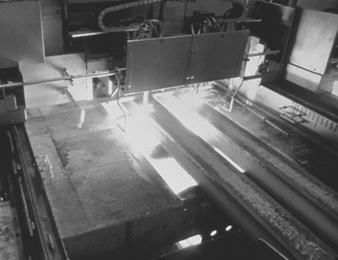

Cold Rolling

Coils of cleaned, hot-rolled sheet steel may be cold rolled to make a product thinner and smoother. This process gives steel a higher strength-to-weight ratio than can be made on a hot mill. A modern five-stand tandem cold mill may receive a sheet about 1/10 inch (0.25 cm) thick and 3/4 of a mile (1.2 km) long; 2 minutes later that sheet will have been rolled to 0.03 inch (75 mm) thick and be more than 2 miles (3.2 km) long.

The cold-rolling process hardens sheet steel so that it usually must be heated in an annealing furnace to make it more formable. Coils of cold-rolled sheets are stacked on a base. Covers are placed over the stacks to control the annealing and then the furnace is lowered over the covered stacks. The heating and re-cooling of sheet steel may take 5 or 6 days.

After the steel has been softened in the annealing process, a temper mill is used to give the steel the desired flatness, metallurgical properties and surface finish. The product may be shipped to consumers as coils or further side-trimmed or sheared into cut lengths.

Hazards and Their Prevention

Accidents. Mechanization has reduced the number of trapping points at machinery but they still exist, especially in cold rolling plants and in finishing departments.

In cold rolling, there is a risk of trapping between the rolls, especially if cleaning in motion is attempted; nips of rolls should be efficiently guarded and strict supervision exercised to prevent cleaning in motion. Severe injuries may be caused by shearing, cropping, trimming and guillotine machines unless the dangerous parts are securely guarded. An effective lockout/tagout programme is essential for maintenance and repair.

Severe injuries may be sustained, especially in hot rolling, if workers attempt to cross roller conveyors at unauthorized points; an adequate number of bridges should be installed and their use enforced. Looping and lashing may cause extensive injuries and burns, even severing of lower limbs; where full mechanization has not eliminated this hazard, protective posts or other devices are necessary.

Special attention should be paid to the hazard of cuts to workers in strip and sheet rolling mills. Such injuries are not only caused by the thin rolled metal, but also by the metal straps used on coils, which may break during handling and constitute a serious hazard.

The use of large quantities of oils, rust inhibitors and so on, which are generally applied by spraying, is another hazard commonly encountered in sheet rolling mills. Despite the protective measures taken to confine the sprayed products, they often collect on the floor and on communication ways, where they may cause slips and falls. Gratings, absorbent materials and boots with non-slip soles should therefore be provided, in addition to regular cleaning of the floor.

Even in automated works, accidents occur in conversion work while changing heavy rollers in the stands. Good planning will often reduce the number of roll changes required; it is important that this work should not be done under pressure of time and that suitable tools be provided.

The automation of modern plants is associated with numerous minor breakdowns, which are often repaired by the crew without stopping the plant or parts of it. In such cases it may happen that it is forgotten to make use of necessary mechanical safeguards, and severe accidents may be the consequence. The fire hazard involved in repairs of hydraulic systems is frequently neglected. Fire protection must be planned and organized with particular care in plants containing hydraulic equipment.

Tongs used to grip hot material may knock together; the square spanners used to move heavy rolled sections by hand may cause serious injuries to the head or upper torso by backlash. All hand tools should be well designed, frequently inspected and well maintained. The tongs used at the mills should have their rivets renewed frequently; ring spanners and impact wrenches should be provided for roll changing crews; bent-out, open-ended spanners should not be used. Workers should receive adequate training in the use of all hand tools. Proper storage arrangements should be made for all hand tools.

Many accidents may be caused by faulty lifting and handling and by defects in cranes and lifting tackle. All cranes and lifting tackle should be under a regular system of examination and inspection; particular care is needed in the storage and use of slings. Crane drivers and slingers should be specially selected and trained. There is always a risk of accidents from mechanical transport: locomotives, wagons and bogies should be well maintained and a well-understood system of warning and signalling should be enforced; clear passage ways should be kept for fork-lifts and other trucks.

Many accidents are caused through falls and stumbles or badly maintained floors, by badly stacked material, by protruding billet ends and cribbing rolls and so on. Hazards can be eliminated by good maintenance of all floor surfaces and means of access, clearly defined walkways, proper stacking of material and regular clearance of debris. Good housekeeping is essential in all parts of the plant including the yards. A good standard of illumination should be kept throughout the plant.

In hot rolling, burns and eye injuries may be caused by flying mill scale; splash guards can effectively reduce the ejection of scale and hot water. Eye injuries may be caused by dust particles or by whipping of cable slings; eyes may also be affected by glare.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is of great importance in the prevention of rolling mill accidents. Hard hats, safety shoes, gaiters, arm protection, gloves, eye shields and goggles should be worn to meet the appropriate risk. It is essential to secure the cooperation of employees in the use of protective devices and the wearing of protective clothing. Training, as well as an effective accident prevention organization in which workers or their representatives participate, is important.

Heat. Radiant heat levels of up to 1,000 kcal/m2 have been measured at work points in rolling mills. Heat stress diseases are a concern, but workers in modern mills usually are protected through the use of air-conditioned pulpits. See the article “Iron and steel making” for information on prevention.

Noise. Considerable noise develops in the entire rolling zone from the gearbox of the rolls and straightening machines, from pressure water pumps, from shears and saws, from throwing finished products into a pit and from stopping movements of the material with metal plates. The general level of operating noises can be around 84-90dBA, and peaks up to 115 dBA or more are not unusual. See the article “Iron and steel making” for information on prevention.

Vibration. Cleaning of the finished products with high-speed percussion tools may lead to arthritic changes of the elbows, shoulders, collarbone, distal ulna and radius joint, as well as lesions of the navicular and lunatum bone.

Joint defects in the hand and arm system may be sustained by rolling mill workers, owing to the recoiling and rebounding effect of the material introduced into the gap between the rolls.

Harmful gases and vapours. When lead-alloyed steel is rolled or cutting-off discs containing lead are used, toxic particles may be inhaled. It is therefore necessary constantly to monitor lead concentrations at the workplace, and workers liable to be exposed should regularly undergo medical examination. Lead may also be inhaled by flame scarfers and gas cutters, who may at the same time be exposed to nitrogen oxides (NOx), chromium, nickel and iron oxide.

Butt welding is associated with the formation of ozone, which may cause, when inhaled, irritation similar to that due to NOx. Pit-furnace and reheating-furnace attendants may be exposed to harmful gases, the composition of which depends on the fuel used (blast-furnace gas, coke-oven gas, oil) and generally includes carbon monoxide and sulphur dioxide. LEV or respiratory protection may be necessary.

Workers lubricating rolling-mill equipment with oil mist may suffer health impairment due to the oils used and to the additives they contain. When oils or emulsions are used for cooling and lubricating, it should be ensured that the proportions of oil and additives are correct in order to preclude not only irritation of the mucosae but also acute dermatitis in exposed workers. See the article “Industrial lubricants, metal working fluids and automotive oils” in the chapter Metal processing and metal working industry.

Large amounts of degreasing agents are used for the finishing operations. These agents evaporate and may be inhaled; their action is not only toxic, but also causes deterioration of the skin, which may be degreased when solvents are not handled properly. LEV should be provided and gloves should be worn.

Acids. Strong acids in pickling shops are corrosive to skin and mucous membranes. Appropriate LEV and PPE should be used.

Ionizing radiation. X rays and other ionizing radiation equipment may be used for gauging and examining; strict precautions in accordance with local regulations are required.

Iron and Steel Industry

Iron is most widely found in the crust of the earth, in the form of various minerals (oxides, hydrated ores, carbonates, sulphides, silicates and so on). Since prehistoric times, humans have learned to prepare and process these minerals by various washing, crushing and screening operations, by separating the gangue, calcining, sintering and pelletizing, in order to render the ores smeltable and to obtain iron and steel. In historic times, a prosperous iron industry developed in many countries, based on local supplies of ore and the proximity of forests to supply the charcoal for fuel. Early in the 18th century, the discovery that coke could be used in place of charcoal revolutionized the industry, making possible its rapid development as the base on which all other developments of the Industrial Revolution rested. Great advantages accrued to those countries where natural deposits of coal and iron ore lay close together.

Steel making was largely a development of the 19th century, with the invention of melting processes; the Bessemer (1855), the open hearth, usually fired by producer gas (1864); and the electric furnace (1900). Since the middle of the 20th century, oxygen conversion, pre-eminently the Linz-Donowitz (LD) process by oxygen lance, has made it possible to manufacture high quality steel with relatively low production costs.

Today, steel production is an index of national prosperity and the basis of mass production in many other industries such as shipbuilding, automobiles, construction, machinery, tools, and industrial and domestic equipment. The development of transport, in particular by sea, has made the international exchange of the raw materials required (iron ores, coal, fuel oil, scrap and additives) economically profitable. Therefore, the countries possessing iron ore deposits near coal fields are no longer privileged, and large smelting plants and steelworks have been built in the coastal regions of major industrialised countries and are supplied with raw materials from exporting countries which are able to meet the present-day requirements for high-grade materials.

During the past decades, so-called direct-reduction processes have been developed and have met with success. The iron ores, in particular high-grade or upgraded ores, are reduced to sponge iron by extracting the oxygen they contain, thus obtaining a ferrous material that replaces scrap.

Iron and Steel Production

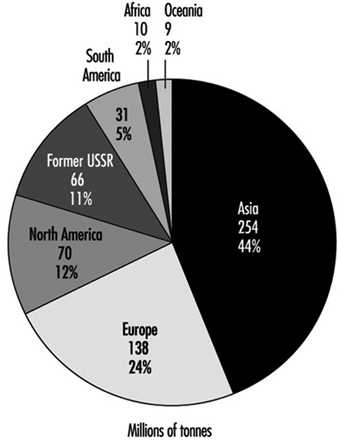

The world’s pig iron production was 578 million tonnes in 1995 (see figure 1).

Figure 1. World pig iron production in 1995, by regions

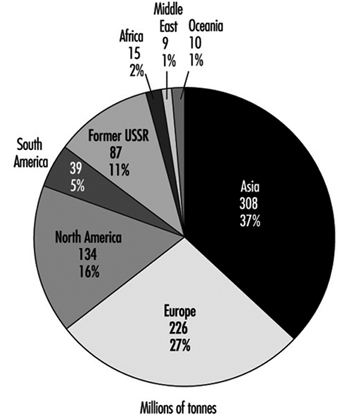

The world’s raw steel production was 828 million tonnes in 1995 (see figure 2).

Figure 2. World raw steel production in 1995, by regions

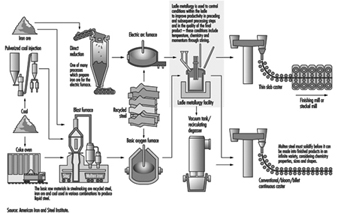

The steel industry has been undergoing a technological revolution, and the trend in building new production capacity has been towards the recycled steel-scrap-using electric arc furnace (EAF) by smaller mills (see figure 3). Although integrated steel works where steel is made from iron ore are operating at record levels of efficiency, EAF steel works with production capacities in the order of less than 1 million tonnes a year are becoming more common in the main steel-producing countries of the world.

Figure 3. Scrap charges or electric furnaces

Iron making

The overall flow line of iron and steel making is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4. Flow line of steel making

For iron making, the essential feature is the blast furnace, where iron ore is melted (reduced) to produce pig iron. The furnace is charged from the top with iron ore, coke and limestone; hot air, frequently enriched with oxygen, is blown in from the bottom; and the carbon monoxide produced from the coke transforms the iron ore into pig iron containing carbon. The limestone acts as a flux. At a temperature of 1,600°C (see figure 5) the pig iron melts and collects at the bottom of the furnace, and the limestone combines with the earth to form slag. The furnace is tapped (i.e., the pig iron is removed) periodically, and the pig iron may then be poured into pigs for later use (e.g., in foundries), or into ladles where it is transferred, still molten, to the steel-making plant.

Figure 5. Taking the temperature of molten metal in a blast furnace

Some large plants have coke ovens on the same site. The iron ores are generally subjected to special preparatory processes before being charged into the blast furnace (washing, reduction to ideal lump size by crushing and screening, separation of fine ore for sintering and pelletizing, mechanized sorting to separate the gangue, calcining, sintering and pelletizing). The slag that is removed from the furnace may be converted on the premises for other uses, in particular for making cement.

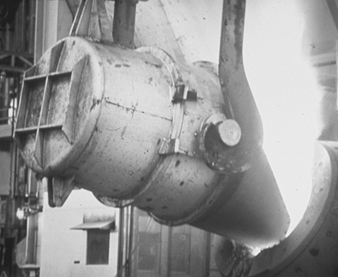

Figure 6. Hot metal charge for basic-oxygen furnace

Steel making

Pig iron contains large amounts of carbon as well as other impurities (mainly sulphur and phosphorus). It must, therefore, be refined. The carbon content must be reduced, the impurities oxidized and removed, and the iron converted into a highly elastic metal which can be forged and fabricated. This is the purpose of the steel-making operations. There are three types of steel-making furnaces: the open-hearth furnace, the basic-oxygen process converter (see figure 6) and the electric arc furnace (see figure 7). Open-hearth furnaces for the most part have been replaced by basic-oxygen converters (where steel is made by blowing air or oxygen into molten iron) and electric arc furnaces (where steel is made from scrap iron and sponge-iron pellets).

Figure 7. General view of electric furnace casting

Special steels are alloys in which other metallic elements are incorporated to produce steels with special qualities and for special purposes, (e.g., chromium to prevent rusting, tungsten to give hardness and toughness at high temperatures, nickel to increase strength, ductility and corrosion resistance). These alloying constituents may be added either to the blast-furnace charge (see figure 8) or to the molten steel (in the furnace or ladle) (see figure 9). Molten metal from the steel-making process is poured into continuous-casting machines to form billets (see figure 10), blooms (see figure 11) or slabs. The molten metal can also be poured into moulds to form ingots. The majority of steel is produced by the casting method (see figure 12). The benefits of continuous casting are increased yield, higher quality, energy savings and a reduction in both capital and operating costs. Ingot-poured moulds are stored in soaking pits (i.e. underground ovens with doors), where ingots can be reheated before passing to the rolling mills or other subsequent processing (figure 4). Recently, companies have begun making steel with continuous casters. Rolling mills are discussed elsewhere in this chapter; foundries, forging and pressing are discussed in the chapter Metal processing and metal working industry.

Figure 8. Back of hot-metal charge

Figure 9. Continuous-casting ladle

Figure 10. Continuous-casting billet

Figure 11. Continuous-casting bloom

Figure 12. Control pulpit for continuous-casting process

Hazards

Accidents

In the iron and steel industry, large amounts of material are processed, transported and conveyed by massive equipment that dwarfs that of most industries. Steel works typically have sophisticated safety and health programmes to address hazards in an environment that can be unforgiving. An integrated approach combining good engineering and maintenance practices, safe job procedures, worker training and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is usually required to control hazards.

Burns may occur at many points in the steel-making process: at the front of the furnace during tapping from molten metal or slag; from spills, spatters or eruptions of hot metal from ladles or vessels during processing, teeming (pouring) or transporting; and from contact with hot metal as it is being formed into a final product.

Water entrapped by molten metal or slag may generate explosive forces that launch hot metal or material over a wide area. Inserting a damp implement into molten metal may also cause violent eruptions.

Mechanical transport is essential in iron and steel manufacturing but exposes workers to potential struck-by and caught- between hazards. Overhead travelling cranes are found in almost all areas of steel works. Most large works also rely heavily on the use of fixed-rail equipment and large industrial tractors for transporting materials.

Safety programmes for crane use require training to ensure proper and safe operation of the crane and rigging of loads to prevent dropped loads; good communication and use of standard hand signals between crane drivers and slingers to prevent injuries from unexpected crane movement; inspection and maintenance programs for crane parts, lifting tackle, slings and hooks to prevent dropped loads; and safe means of access to cranes to avoid falls and accidents on crane transverse ways.

Safety programmes for railways also require good communication, especially during shifting and coupling of rail cars, to avoid catching people between rail car couplings.

Maintaining proper clearance for passage of large industrial tractors and other equipment and preventing unexpected start-up and movement are necessary to eliminate struck-by, struck-against and caught-between hazards to equipment operators, pedestrians and other vehicle operators. Programmes are also necessary for inspection and maintenance of equipment safety appliances and passageways.

Good housekeeping is a cornerstone of safety in iron and steel works. Floors and passageways can quickly become obstructed with material and implements that pose a tripping hazard. Large quantities of greases, oils and lubricants are used and if spilled can easily become a slipping hazard on walking or working surfaces.

Tools are subject to heavy wear and soon become compromised and perhaps dangerous to use. Although mechanization has greatly lessened the amount of manual handling in the industry, ergonomic strains still may occur on many occasions.

Sharp engines or burrs on steel products or metal bands pose laceration and puncture hazards to workers involved in finishing, shipping and scrap-handling operations. Cut-resistant gloves and wrist guards are often used to eliminate injuries.

Protective eye-wear programmes are particularly important in iron and steel works. Foreign-body eye hazards are prevalent in most areas, especially in raw material handling and steel finishing, where grinding, welding and burning are conducted.

Programmed maintenance is particularly important for accident prevention. Its purpose is to ensure the efficiency of the equipment and maintain fully operative guards, because failure may cause accidents. Adhering to safe operating practices and safety rules is also very important because of the complexity, size and speed of process equipment and machinery.

Carbon monoxide poisoning

Blast furnaces, converters and coke ovens produce large quantities of gases in the process of iron and steel manufacturing. After the dust has been removed, these gases are used as fuel sources in the various plants, and some are supplied to chemical plants for use as raw materials. They contain large amounts of carbon monoxide (blast-furnace gas, 22 to 30%; coke oven gas, 5 to 10%; converter gas, 68 to 70%).

Carbon monoxide sometimes emanates or leaks from the tops or bodies of blast furnaces or from the many gas pipelines inside plants, accidentally causing acute carbon monoxide poisoning. Most cases of such poisoning occur during work around blast furnaces, especially during repairs. Other cases occur during work around hot stoves, tours of inspection around the furnace bodies, work near the furnace tops or work near cinder notches or the tapping notches. Carbon monoxide poisoning may also result from gas released from water-seal valves or seal pots in the steel-making plants or rolling mills; from sudden shutdown of blowing equipment, boiler rooms or ventilation fans; from leakage; from failure to properly ventilate or purge process vessels, pipelines or equipment prior to work; and during closing of pipe valves.

Dust and fumes

Dust and fumes are generated at many points in the manufacture of iron and steel. Dust and fumes are found in the preparation processes, especially sintering, in front of the blast furnaces and steel furnaces and in ingot making. Dusts and fumes from iron ore or ferrous metals do not readily cause pulmonary fibrosis and pneumoconiosis is infrequent. Some lung cancers are thought to be connected with carcinogens found in coke-oven emissions. Dense fumes emitted during the use of oxygen lances and from the use of oxygen in open-hearth furnaces may particularly affect crane operators.

Exposure to silica is a risk to workers engaged in lining, relining and repairing blast furnaces and steel furnaces and vessels with refractory materials, which may contain as much as 80% silica. Ladles are lined with fire-brick or bonded crushed silica and this lining requires frequent repair. The silica contained in refractory materials is partly in the form of silicates, which do not cause silicosis but rather pneumoconiosis. Workers are rarely exposed to heavy clouds of dust.

Alloy additions to furnaces making special steels sometimes bring potential exposure risks from chromium, manganese, lead and cadmium.

Miscellaneous hazards

Bench and top-side operations in coking operations in front of blast furnaces in iron making and furnace-front, ingot-making and continuous-casting operations in steel making all involve strenuous activities in a hot environment. Heat-illness prevention programmes must be implemented.

Furnaces may cause glare that can injure eyes unless suitable eye protection is provided and worn. Manual operations, such as furnace bricklaying, and hand-arm vibration in chippers and grinders may cause ergonomic problems.

Blower plants, oxygen plants, gas-discharge blowers and high-power electric furnaces may cause hearing damage. Furnace operators should be protected by enclosing the source of noise with sound-deadening material or by providing sound-proofed shelters. Reducing exposure time may also prove effective. Hearing protectors (earmuffs or earplugs) are often required in high-noise areas due to the unfeasibility of obtaining adequate noise reduction by other means.

Safety and Health Measures

Safety organization

Safety organization is of prime importance in the iron and steel industry, where safety depends so much on workers’ reaction to potential hazards. The first responsibility for management is to provide the safest possible physical conditions, but it is usually necessary to obtain everyone’s cooperation in safety programmes. Accident-prevention committees, workers’ safety delegates, safety incentives, competitions, suggestion schemes, slogans and warning notices can all play an important part in safety programmes. Involving all persons in site hazard assessments, behaviour observation and feedback exercises can promote positive safety attitudes and focus work groups working to prevent injuries and illnesses.

Accident statistics reveal danger areas and the need for additional physical protection as well as greater stress on housekeeping. The value of different types of protective clothing can be evaluated and the advantages can be communicated to the workers concerned.

Training

Training should include information about hazards, safe methods of work, avoidance of risks and the wearing of PPE. When new methods or processes are introduced, it may be necessary to retrain even those workers with long experience on older types of furnaces. Training and refresher courses for all levels of personnel are particularly valuable. They should familiarize personnel with safe working methods, unsafe acts to be proscribed, safety rules and the chief legal provisions associated with accident prevention. Training should be conducted by experts and should make use of effective audio-visual aids. Safety meetings or contacts should be held regularly for all persons to reinforce safety training and awareness.

Engineering and administrative measures

All dangerous parts of machinery and equipment, including lifts, conveyors, long travel shafts and gearing on overhead cranes, should be securely guarded. A regular system of inspection, examination and maintenance is necessary for all machinery and equipment of the plant, particularly for cranes, lifting tackle, chains and hooks. An effective lockout/tagout programme should be in operation for maintenance and repair. Defective tackle should be scrapped. Safe working loads should be clearly marked, and tackle not in use should be stored neatly. Means of access to overhead cranes should, where possible, be by stairway. If a vertical ladder must be used, it should be hooped at intervals. Effective arrangements should be made to limit the travel of overhead cranes when persons are at work in the vicinity. It may be necessary, as required by law in certain countries, to install appropriate switchgear on overhead cranes to prevent collisions if two or more cranes travel on the same runway.

Locomotives, rails, wagons, buggies and couplings should be of good design and maintained in good repair, and an effective system of signalling and warning should be in operation. Riding on couplings or passing between wagons should be prohibited. No operation should be carried on in the track of rail equipment unless measures have been taken to restrict access or movement of equipment.

Great care is needed in storing oxygen. Supplies to different parts of the works should be piped and clearly identified. All lances should be kept clean.

There is a never-ending need for good housekeeping. Falls and stumbles caused by obstructed floors or implements and tools left lying carelessly can cause injury in themselves but can also throw a person against hot or molten material. All materials should be carefully stacked, and storage racks should be conveniently placed for tools. Spills of grease or oil should be immediately cleaned. Lighting of all parts of the shops and machine guards should be of a high standard.

Industrial hygiene

Good general ventilation throughout the plant and local exhaust ventilation (LEV) wherever substantial quantities of dust and fumes are generated or gas may escape are necessary, together with the highest possible standards of cleanliness and housekeeping. Gas equipment must be regularly inspected and well maintained so as to prevent any gas leakage. Whenever any work is to be done in an environment likely to contain gas, carbon monoxide gas detectors should be used to ensure safety. When work in a dangerous area is unavoidable, self-contained or supplied-air respirators should be worn. Breathing-air cylinders should always be kept in readiness, and the operatives should be thoroughly trained in methods of operating them.

With a view to improving the work environment, induced ventilation should be installed to supply cool air. Local blowers may be located to give individual relief, especially in hot working places. Heat protection can be provided by installing heat shields between workers and radiant heat sources, such as furnaces or hot metal, by installing water screens or air curtains in front of furnaces or by installing heat-proof wire screens. A suit and hood of heat-resistant material with air-line breathing apparatus gives the best protection to furnace workers. As work in the furnaces is extremely hot, cool-air lines may also be led into the suit. Fixed arrangements to allow cooling time before entry into the furnaces are also essential.

Acclimatization leads to natural adjustment in the salt content of body sweat. The incidence of heat affections may be much lessened by adjustments of the workload and by well-spaced rest periods, especially if these are spent in a cool room, air- conditioned if necessary. As palliatives, a plentiful supply of water and other suitable beverages should be provided and there should be facilities for taking light meals. The temperature of cool drinks should not be too low and workers should be trained not to swallow too much cool liquid at a time; light meals are to be preferred during working hours. Salt replacement is needed for jobs involving profuse sweating and is best achieved by increasing salt intake with regular meals.

In cold climates, care is required to prevent the ill-effects of prolonged exposure to cold or sudden and violent changes of temperature. Canteen, washing and sanitary facilities should preferably be close at hand. Washing facilities should include showers; changing rooms and lockers should be provided and maintained in a clean and sanitary condition.

Wherever possible, sources of noise should be isolated. Remote central panels remove some operatives from the noisy areas; hearing protection should be required in the worst areas. In addition to enclosing noisy machinery with sound-absorbing material or protecting the workers with sound-proofed shelters, hearing protection programmes have been found to be effective means of controlling noise-induced hearing loss.

Personal protective equipment

All parts of the body are at risk in most operations, but the type of protective wear required will vary according to the location. Those working at furnaces need clothing that protects against burns—overalls of fire-resisting material, spats, boots, gloves, helmets with face shields or goggles against flying sparks and also against glare. Safety boots, safety glasses and hard hats are imperative in almost all occupations and gloves are widely necessary. The protective clothing needs to take account of the risks to health and comfort from excessive heat; for example a fire-resisting hood with wire mesh visor gives good protection against sparks and is resistant to heat; various synthetic fibres have also proved efficient in heat resistance. Strict supervision and continuous propaganda are necessary to ensure that personal protective equipment is worn and correctly maintained.

Ergonomics

The ergonomic approach (i.e. investigation of the worker-machine-environment relationship) is of particular importance at certain operations in the iron and steel industry. An appropriate ergonomic study is necessary not only to investigate conditions while a worker is carrying out various operations, but also to explore the impact of the environment on the worker and the functional design of the machinery used.

Medical supervision

Pre-placement medical examinations are of great importance in selecting persons suitable for the arduous work in iron and steel making. For most work, a good physique is required: hypertension, heart diseases, obesity and chronic gastroenteritis disqualify individuals from work in hot surroundings. Special care is needed in the selection of crane drivers, both for physical and mental capacities.

Medical supervision should pay particular attention to those exposed to heat stress; periodic chest examinations should be provided for those exposed to dust, and audiometric examinations for those exposed to noise; mobile equipment operators should also receive periodic medical examinations to ensure their continued fitness for the job.

Constant supervision of all resuscitative appliances is necessary, as is training of workers in first-aid revival procedure.

A central first-aid station with the requisite medical equipment for emergency assistance should also be provided. If possible, there should be an ambulance for the transport of severely injured persons to the nearest hospital under the care of a qualified ambulance attendant. In larger plants first-aid stations or boxes should be located at several central points.

Coke Operations

Coal preparation

The most important single factor for producing metallurgical coke is the selection of coals. Coals with low ash and low sulphur content are most desirable. Low-volatile coal in amounts up to 40% are usually blended with high-volatile coal to achieve the desired characteristics. The most important physical property of metallurgical coke is its strength and ability to withstand breakage and abrasion during handling and use in the blast furnace. The coal-handling operations consist of unloading from railroad cars, marine barges or trucks; blending of the coal; proportioning; pulverizing; bulk-density control using diesel grade or similar oil; and conveying to the coke battery bunkers.

Coking

For the most part coke is produced in by-product coking ovens that are designed and operated to collect the volatile material from the coal. The ovens consist of three main parts: the coking chambers, the heating flues and the regenerative chamber. Apart from the steel and concrete structural support, the ovens are constructed of refractory brick. Typically each battery contains approximately 45 separate ovens. The coking chambers are generally 1.82 to 6.7 metres in height, 9.14 to 15.5 metres in length and 1,535 °C at the heating flue base. The time required for coking varies with oven dimensions, but usually ranges between 16 and 20 hours.

In large vertical ovens, the coal is charged through openings in the top from a rail-type “larry car” that transports the coal from the coal bunker. After the coal has become coke, the coke is pushed out of the oven from one side by a power-driven ram or “pusher”. The ram is slightly smaller than the oven dimensions so that contact with the oven interior surfaces is avoided. The coke is collected in a rail-type car or in the side of the battery opposite the pusher and transported to the quenching facility. The hot coke is wet quenched with water prior to discharge on the coke wharf. At some batteries, the hot coke is dry quenched to recover sensible heat for the generation of steam.

The reactions during the carbonization of coal for the production of coke are complex. Coal decomposition products initially include water, oxides of carbon, hydrogen sulphide, hydro-aromatic compounds, paraffins, olefins, phenolic and nitrogen-containing compounds. Synthesis and degradation occur among the primary products that produce large amounts of hydrogen, methane, and aromatic hydrocarbons. Further decomposition of the complex nitrogen containing compounds produce ammonia, hydrogen cyanide, pyridine bases and nitrogen. The continual removal of hydrogen from the residue in the oven produces hard coke.

The by-product coke ovens that have equipment for recovering and processing coal chemicals produce the materials listed in table 1.

Table 1. Recoverable by-products of coke ovens

|

By-product |

Recoverable constituents |

|

Coke oven gas |

Hydrogen, methane, ethane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, ethylene, |

|

Ammonia liquor |

Free and fixed ammonia |

|

Tar |

Pyridine, tar acids, naphthalene, creosote oil and coal-tar pitch |

|

Light oil |

Varying amounts of coal gas products with boiling points from about 40 ºC |

After sufficient cooling so that conveyor-belt damage will not occur, the coke is moved to the screening and crushing station where it is sized for blast-furnace use.

Hazards

Physical hazards

During the coal unloading, preparation and handling operations, thousands of tonnes of coal are manipulated, producing dust, noise and vibrations. The presence of large quantities of accumulated dust can produce an explosion hazard in addition to the inhalation hazard.

During coking, ambient and radiant heat are the major physical concerns, particularly on the topside of the batteries, where the majority of the workers are deployed. Noise may be a problem in mobile equipment, primarily from drive mechanism and vibrating components that are not adequately maintained. Ionizing radiation and/or laser producing devices may be used for mobile equipment alignment purposes.

Chemical hazards

Mineral oil is typically used for operation purposes for bulk density control and dust suppression. Materials may be applied to the coal prior to being taken to the coal bunker to minimize the accumulation and to facilitate the disposal of hazardous waste from the by-products operations.

The major health concern associated with coking operations is emissions from the ovens during charging of the coal, coking and pushing of the coke. The emissions contain numerous polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), some of which are carcinogenic. Materials utilized for sealing leaks in lids and doors may also be a concern during mixing and when lids and doors are removed. Asbestos and refracting ceramic filters may also be present in the form of insulating materials and gaskets, although suitable replacements have been used for products that previously contained asbestos.

Mechanical hazards

The coal-production hazards associated with railroad car, marine barge and vehicular traffic as well as conveyor belt movement must be recognized. The majority of accidents occur when workers are struck by, caught between, fall from, are entrained and entrapped in, or fail to lockout such equipment (including electrically).

The mechanical hazards of greatest concern are associated with the mobile equipment on the pusher side, coke side and the larry car on top of the battery. This equipment is in operation practically the entire work period and little space is provided between it and the operations. Caught-between and struck-by accidents associated with mobile rail-type equipment account for the highest number of fatal coke-oven production incidents. Skin surface burns from hot materials and surfaces and eye irritation from dust particles are responsible for more numerous, less severe occurrences.

Safety and Health Measures

To maintain dust concentrations during coal production at acceptable levels, containment and enclosure of screening, crushing and conveying systems are required. LEV may also be required in addition to wetting agents applied to the coal. Adequate mainten- ance programmes, belt programmes and clean-up programmes are required to minimize spillage and keep passageways alongside process and conveying equipment clear of coal. The conveyor system should use components known to be effective in reducing spillage and maintaining containment, such as belt cleaners, skirt boards, proper belt tension and so on.

Due to the health hazards associated with the PAHs released during the coking operations, it is important to contain and collect these emissions. This is best accomplished by a combination of engineering controls, work practices and a maintenance programme. It is also necessary to have an effective respirator programme. The controls should include the following:

- a charging procedure designed and operated to eliminate emissions by controlling the volume of coal being charged, properly aligning the car over the oven, tightly fitting drop sleeves and charging the coal in a sequence that allows an adequate channel on top of the coal to be maintained for flow of emissions to the collector mains and relidding immediately after charging

- drafting from two or more points in the oven being charged and an aspiration system designed and operated to maintain sufficient negative pressure and flow

- air seals on the pusher machine level bars to control infiltration during charging and carbon cutters to remove carbon build-up

- uniform collector-main pressure adequate to convey the emissions

- chuck door and gaskets as needed to maintain a tight seal and adequately cleaned and maintained pusher side and coke side sealing edges

- luting of lids and doors and maintaining door seals as necessary to control emissions after charging

- green pushes minimized by heating the coal uniformly for an adequate period

- installation of large enclosures over the entire coke side area to control emissions during the pushing of coke or use of travelling hoods to be moved to the individual ovens being pushed

- routine inspection, maintenance and repair for proper containment of emissions

- positive-pressure and temperature controlled operator cabs on mobile equipment to control worker exposure levels. To achieve the positive-pressure cab, structural integration is imperative, with tight fitting doors and windows and the elimination of separations in structural work.

Worker training is also necessary so that proper work practices are used and the importance of proper procedures to minimize emissions is understood.

Routine worker exposure monitoring should also be used to determine that levels are acceptable. Gas monitoring and rescue programmes should be in place, primarily due to the presence of carbon monoxide in coke-gas ovens. A medical surveillance programme should also be implemented.

Physical Load

Manual Forest Work

Workload. Manual forest work generally carries a high physical workload. This in turn means a high energy expenditure for the worker. The energy output depends on the task and the pace at which it is performed. The forest worker needs a much larger food intake than the “ordinary” office worker to cope with the demands of the job.

Table 1 presents a selection of jobs typically performed in forestry, classified into categories of workload by the energy expenditure required. The figures can give only an approximation, as they depend on body size, sex, age, fitness and work pace, as well as on tools and working techniques. It does, however, give a broad indication that nursery work is generally light to moderate; planting work and harvesting with a chain-saw moderate to heavy; and manual harvesting heavy to very heavy. (For case-studies and a detailed discussion of the workload concept applied to forestry see Apud et al. 1989; Apud and Valdés 1995; and FAO 1992.)

Table 1. Energy expenditure in forestry work.

|

|

Kj/min/65 kg man |

Workload capacity |

||||||

|

|

Range |

Mean |

|

|||||

|

Work in forestry nursery |

||||||||

|

Cultivating tree plants |

|

|

18.4 |

L |

||||

|

Hoeing |

|

|

24.7 |

M |

||||

|

Weeding |

|

|

19.7 |

L |

||||

|

Planting |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Clearing draining ditches with spade |

|

|

32.7 |

H |

||||

|

Tractor driving/harrowing while sitting |

|

14.2-22.6 |

19.3 |

L |

||||

|

Planting by hand |

|

23.0-46.9 |

27.2 |

M |

||||

|

Planting by machine |

|

|

11.7 |

L |

||||

|

Work with axe-Horizontal and perpendicular blows |

||||||||

|

Weight of axe head |

Rate (blows/min) |

|

|

|

||||

|

1.25 kg |

20 |

|

23.0 |

M |

||||

|

0.65-1.25 kg |

35 |

38.0-44.4 |

41.0 |

VH |

||||

|

Felling, trimming, etc. with hand tools |

||||||||

|

Felling |

|

28.5-53.2 |

36.0 |

H |

||||

|

Carrying logs |

|

41.4-60.3 |

50.7 |

EH |

||||

|

Dragging logs |

|

34.7-66.6 |

50.7 |

EH |

||||

|

Work with saw in forest |

||||||||

|

Carrying power saw |

|

|

27.2 |

M |

||||

|

Cross-cutting by hand |

|

26.8-44.0 |

36.0 |

H |

||||

|

Horizontal-sawing power saw |

|

15.1--26.8 |

22.6 |

M |

||||

|

Mechanized logging |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Operating harvester/forwarder |

|

12-20 |

|

L |

||||

|

Fuelwood preparation |

||||||||

|

Sawing small logs by hand |

|

|

15.1 |

L |

||||

|

Cleaving wood |

|

36.0-38.1 |

36.8 |

H |

||||

|

Dragging firewood |

|

32.7-41.0 |

36.8 |

H |

||||

|

Stacking firewood |

|

21.3-26.0 |

23.9 |

M |

||||

L = Light; M = Moderate; H = Heavy; VH = Very heavy; EH = Extremely heavy

Source: Adapted from Durnin and Passmore 1967.

Musculoskeletal strain. Manual piling involves repeated heavy lifting. If the working technique is not perfect and the pace too high, the risk of musculoskeletal injuries (MSIs) is very high. Carrying heavy loads over extended periods of time, such as in pulpwood harvesting or fuelwood harvesting and transport, has a similar impact.

A specific problem is the use of maximum body force, which could lead to sudden musculoskeletal injuries in certain situations. An example is bringing down a badly hung-up tree by using a felling lever. Another is “saving” a falling log from a pile.

The work is done using only muscle force, and most often it involves dynamic and not simply repetitive use of the same muscle groups. It is not static. The risk for repetitive strain injuries (RSIs) is usually small. However, working in awkward body positions can create problems such as low-back pain. An example is using an axe to delimb trees which are lying on the ground, which requires working bent over for long periods of time. This puts great strain on the lower back and also means that the muscles in the back do static work. The problem can be reduced by felling trees across a stem that is already on the ground, thus using it as a natural workbench.

Motor-Manual Forest Work

The operation of portable machines such as chain-saws may require even greater energy expenditure than manual work, because of their considerable weight. In fact, the chain-saws used are often too big for the task at hand. Instead, the lightest model and the smallest guide bar possible should be used.

Whenever a forest worker who uses machines also does the piling manually, he or she is exposed to the problems described above. Workers have to be instructed to keep the back straight and to rely on the big muscles in the legs to lift loads.

The work is done using machine power and is more static than manual work. The operator’s work consists of choosing, moving and holding the machine in the right position.

Many of the problems created originate from working at a low height. Delimbing a tree that is lying flat on the ground means working bent over. This is a similar problem to that described in manual forest work. The problem is compounded when carrying a heavy chain-saw. Work should be planned and organized so the working height is close to the hip of the forest worker (e.g., using other trees as “workbenches” for delimbing, as described above). The saw should be supported by the stem as much as possible.

Highly specialized motor-manual work tasks create very high risk for musculoskeletal injuries since the work cycles are short and the specific movements are repeated many times. An example is the fellers working with chain-saws ahead of a processor (delimbing and cutting). Most of these forest workers that were studied in Sweden had neck and shoulder problems. Doing the whole logging operation (felling, delimbing, crosscutting and certain not-too-heavy piling) means the job is more varied and the exposure to specific unfavourable static, repetitive work is reduced. Even with the appropriate saw and a good working technique, chain-saw operators should not work more than 5 hours a day with the saw running.

Machine Work

The physical workloads in most forest machines are very low compared to manual or motor-manual work. The machine operator or the mechanic is still sometimes exposed to heavy lifting during maintenance and repairs. The operator’s work consists of guiding the movements of the machine. He or she controls the force to be exerted by handles, levers, buttons and so on. The work cycles are very short. The work for the most part is repetitive and static, which can lead to a high risk for RSIs in the neck, shoulder, arm, hand or finger regions.

In machinery from the Nordic countries the operator works only with very small tensions in the muscles, using mini–joy sticks, sitting in an ergonomic seat with armrests. But still RSIs are a major problem. Studies show that between 50 and 80% of machine operators have neck or shoulder complaints. These figures are often difficult to compare since the injuries develop gradually over a long period of time. The results depend on the definition of injury or complaints.

Repetitive strain injuries depend on many things in the work situation:

Degree of tension in the muscle. A high static or repeated, monotonous muscle tension can be caused, for example, by using heavy controls, by awkward working positions or whole-body vibrations and shocks, but also by high mental stress. Stress can be generated by high concentration, complicated decisions or by the psychosocial situation, such as lack of control over the work situation and relations with supervisors and workmates.

Time of exposure to static work. Continuous static muscle tensions can be broken only by taking frequent pauses and micropauses, by changing work tasks, by job rotation and so on. A long total exposure to monotonous, repetitive work movements over the years increases the risk of RSIs. The injuries appear gradually and may be irreversible when manifested.

Individual status (“resistance”). The “resistance” of the individual changes over time and depends on his or her inherited predisposition and physical, psychological and social status.

Research in Sweden has shown that the only way to reduce these problems is by working with all these factors, especially through job rotation and job enlargement. These measures decrease the time of exposure and improve the well-being and psychosocial situation of the worker.

The same principles can be applied to all forest work—manual, motor-manual or machine work.

Combinations of Manual, Motor-Manual and Machine Work

Combinations of manual and machine work without job rotation always mean that the work tasks become more specialized. An example is the motor-manual fellers working ahead of a processor which is delimbing and cutting. The work cycles for the fellers are short and monotonous. The risk of MSIs and RSIs is very high.

A comparison between chain-saw and machine operators was made in Sweden. It showed that the chain-saw operators had higher risks of MSIs in the low back, knees and hip as well as high risks of hearing impairment. The machine operators on the other hand had higher risks of RSIs in the neck and shoulders. The two types of work were subject to very different hazards. A comparison with manual work would probably show still another risk pattern. Combinations of different types of work tasks using job rotation and job enlargement give possibilities to reduce the time of exposure for many specific hazards.

Physical Safety Hazards

Climate, noise and vibration are common physical hazards in forestry work. Exposure to physical hazards varies greatly depending on the type of work and the equipment used. The following discussion concentrates on forest harvesting and considers manual work and motor-manual (mostly chain-saws) and mechanized operations.

Manual Forest Work

Climate

Working outdoors, subject to climatic conditions, is both positive and negative for the forest worker. Fresh air and nice weather are good, but unfavourable conditions can create problems.

Working in a hot climate puts pressure on the forest worker engaged in heavy work. Among other things, the heart rate increases to keep the body temperature down. Sweating means loss of body fluids. Heavy work in high temperatures means that a worker might need to drink 1 litre of water per hour to keep the body fluid balance.

In a cold climate the muscles function poorly. The risk of musculoskeletal injuries (MSI) and accidents increases. In addition, energy expenditure increases substantially, since it takes a lot of energy just to keep warm.

Rainy conditions, especially in combination with cold, mean higher risk of accidents, since tools are more difficult to grasp. They also mean that the body is even more chilled.

Adequate clothing for different climatic conditions is essential to keep the forest worker warm and dry. In hot climates only light clothing is required. It is then rather a problem to use sufficient protective clothing and footwear to protect him or her against thorns, whipping branches and irritating plants. Lodgings must have sufficient washing and drying facilities for clothes. Improved conditions in camps have in many countries substantially reduced the problems for the workers.

Setting limits for acceptable weather conditions for work based only on temperature is very difficult. For one thing the temperature varies quite a lot between different places in the forest. The effect on the person also depends on many other things such as humidity, wind and clothing.

Tool-related hazards

Noise, vibrations, exhaust gases and so on are seldom a problem in manual forest work. Shocks from hitting hard knots during delimbing with an axe or hitting stones when planting might create problems in elbows or hands.

Motor-Manual Forest Work

The motor-manual forest worker is one who works with hand-held machines such as chain-saws or power brush cutters and is exposed to the same climatic conditions as the manual worker. He or she therefore has the same need for adequate clothing and lodging facilities. A specific problem is the use of personal protective equipment in hot climates. But the worker is also subject to other specific hazards due to the machines he or she is working with.

Noise is a problem when working with a chain-saw, brush saw or the like. The noise level of most chain-saws used in regular forest work exceeds 100 dBA. The operator is exposed to this noise level for 2 to 5 hours daily. It is difficult to reduce the noise levels of these machines without making them too heavy and awkward to work with. The use of ear protectors is therefore essential. Still, many chain-saw operators suffer loss of hearing. In Sweden around 30% of chain-saw operators had a serious hearing impairment. Other countries report high but varying figures depending on the definition of hearing loss, the duration of exposure, the use of ear protectors and so on.

Hand-induced vibration is another problem with chain-saws. “White finger” disease has been a major problem for some forest workers operating chain-saws. The problem has been brought to a minimum with modern chain-saws. The use of efficient anti-vibration dampers (in cold climates combined with heated handles) has meant, for instance, that in Sweden the number of chain-saw operators suffering from white fingers has dropped to 7 or 8%, which corresponds to the overall figure for natural white fingers for all Swedes. Other countries report large numbers of workers with white finger, but these probably do not use modern, vibration-reduced chain-saws.

The problem is similar when using brush saws and pruning saws. These types of machines have not been under close study, since in most cases the time of exposure is short.

Recent research points to a risk of loss of muscle strength due to vibrations, sometimes even without white finger symptoms.

Machine Work

Exposure to unfavourable climatic conditions is easier to solve when machines have cabins. The cabin can be insulated from cold, provided with air-conditioning, dust filters and so on. Such improvements cost money, so in most older machines and in many new ones the operator is still exposed to cold, heat, rain and dust in a more or less open cabin.

Noise problems are solved in a similar manner. Machines used in cold climates such as the Nordic countries need efficient insulation against cold. They also most often have good noise protection, with noise levels down to 70 to 75 dBA. But machines with open cabins most often have very high noise levels (over 100 dBA).

Dust is a problem especially in hot and dry climates. A cabin well insulated against cold, heat or noise also helps keep out the dust. By using a slight overpressure in the cabin, the situation can be improved even more.

Whole-body vibration in forest machines can be induced by the terrain over which the machine travels, the movement of the crane and other moving parts of the machine, and the vibrations from the power transmission. A specific problem is the shock to the operator when the machine comes down from an obstacle such as a rock. Operators of cross-country vehicles, such as skidders and forwarders, often have problems with low-back pain. The vibrations also increase the risk of repetitive strain injuries (RSI) to the neck, shoulder, arm or hand. The vibrations increase strongly with the speed at which the operator drives the machine.

In order to reduce vibrations, machines in the Nordic countries use vibration-damping seats. Other ways are to reduce the shocks coming from the crane by making it work smoother technically and by using better working techniques. This also makes the machine and the crane last longer. A new interesting concept is the “Pendo cabin”. This cabin hangs on its “ears” connected to the rest of the machine by only a stand. The cabin is sealed off from the noise sources and is easier to protect from vibrations. The results are good.

Other approaches try to reduce the shocks that arise from driving over the terrain. This is done by using “intelligent” wheels and power transmission. The aim is to lower environmental impact, but it also has a positive effect on the situation for the operator. Less expensive machines most often have little reduction of noise, dust and vibration. Vibration may also be a problem in handles and controls.

When no engineering approaches to controlling the hazards are used, the only available solution is to reduce the hazards by lowering the time of exposure, for instance, by job rotation.

Ergonomic checklists have been designed and used successfully to evaluate forestry machines, to guide the buyer and to improve machine design (see Apud and Valdés 1995).

Combinations of Manual, Motor-Manual and Machine Work

In many countries, manual workers work together with or close to chain-saw operators or machines. The machine operator sits in a cabin or uses ear protectors and good protective equipment. But, in most cases the manual workers are not protected. The safety distances to the machines are not adhered to, resulting in very high risk of accidents and risk of hearing damage to unprotected workers.

Job Rotation

All the above-described hazards increase with the duration of exposure. To reduce the problems, job rotation is the key, but care has to be taken not to merely change work tasks while in actuality maintaining the same type of hazards.

Forest Fire Management and Control

The Relevance of Forest Fires

One important task for forest management is the protection of the forest resource base.

Out of many sources of attacks against the forest, fire is often the most dangerous. This danger is also a real threat for the people living inside or adjacent to the forest area. Each year thousands of people lose their homes due to wildfires, and hundreds of people die in these accidents; additionally tens of thousands of domestic animals perish. Fire destroys agricultural crops and leads to soil erosion, which in the long run is even more disastrous than the accidents described before. When the soil is barren after the fire, and heavy rains soak the soil, huge mud- or landslides can occur.

It is estimated that every year:

- 10 to 15 million hectares of boreal or temperate forest burn.

- 20 to 40 million hectares of tropical rain forest burn.

- 500 to 1,000 million hectares of tropical and subtropical savannahs, woodlands and open forests burn.

More than 90% of all this burning is caused by human activity. Therefore, it is quite clear that fire prevention and control should receive top priority among forest management activities.

Risk Factors in Forest Fires

The following factors make fire-control work particularly difficult and dangerous:

- excessive heat radiated by the fire (fires always occur during hot weather)

- poor visibility (due to smoke and dust)

- difficult terrain (fires always follow wind patterns and generally move uphill)

- difficulty getting supplies to the fire-fighters (food, water, tools, fuel)

- often obligatory to work at night (easiest time to “kill” the fire)

- impossibility of outrunning a fire during strong winds (fires move faster than any person can run)

- sudden changes in the wind direction, so that no one can exactly predict the spread of the fire

- stress and fatigue, causing people to make disastrous judgement errors, often with fatal results.

Activities in Forest Fire Management

The activities in forest fire management can be divided into three different categories with different objectives:

- fire prevention (how to prevent fires from happening)

- fire detection (how to report the fires as fast as possible)

- fire suppression (the work to put out the fire, actually fighting the fire).

Occupational dangers

Fire prevention work is generally a very safe activity.

Fire detection safety is mostly a question of safe driving of vehicles, unless aircraft are used. Fixed-wing aircraft are especially vulnerable to strong uplifting air streams caused by the hot air and gases. Each year tens of air crews are lost due to pilot errors, especially in mountainous conditions.

Fire suppression, or actual fighting of the fire, is a very specialized operation. It has to be organized like a military operation, because negligence, non-obedience and other human errors may not only endanger the firefighter, but may also cause the death of many others as well as extensive property damage. The whole organization has to be clearly structured with good coordination between forestry staff, emergency services, fire brigades, police and, in large fires, the armed forces. There has to be a single line of command, centrally and onsite.

Fire suppression mostly involves the establishment or maintenance of a network of fire-breaks. These are typically 10- to 20-metre-wide strips cleared of all vegetation and burnable material. Accidents are mostly caused by cutting tools.

Major wildfires are, of course, the most hazardous, but similar problems arise with prescribed burning or “cold fires”, when mild burns are allowed to reduce the amount of inflammable material without damaging the vegetation. The same precautions apply in all cases.

Early intervention

Detecting the fire early, when it is still weak, will make its control easier and safer. Previously, detection was based on observations from the ground. Now, however, infrared and microwave equipment attached to aircraft can detect an early fire. The information is relayed to a computer on the ground, which can process it and give the precise location and temperature of the fire, even when there are clouds. This allows ground crews and/or smoke jumpers to attack the fire before it spreads widely.

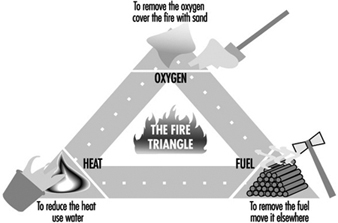

Tools and equipment

Many rules are applicable to the firefighter, who may be a forest worker, a volunteer from the community, a government employee or a member of a military unit ordered to the area. The most important is: never go to fight a fire without your own personal cutting tool. The only way to escape the fire may be to use the tool to remove one of the components of the “fire triangle”, as shown in figure 1. The quality of that tool is critical: if it breaks, the fire fighter may lose his or her life.

Figure 1. Forest firefighter safert equipment

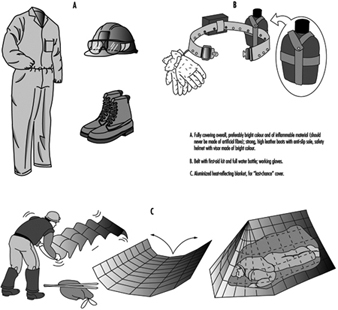

This also puts a very special emphasis on the quality of the tool; bluntly put, if the metal part of the tool breaks, the fire-fighter may lose his or her life. Forest firefighter safety equipment is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Forest firefighter safety equipment

Terrestrial firefighting

The preparation of fire breaks during an actual fire is especially dangerous because of the urgency of controlling the advance of the fire. The danger may be multiplied by poor visibility and changing wind direction. In fighting fires with heavy smoke (e.g., peat-land fires), lessons learned from such a fire in Finland in 1995 include:

- Only experienced and physically very fit people should be sent out in heavy smoke conditions.

- Each person should have a radio to receive directions from an hovering aircraft.

- Only people with breathing apparatus or gas masks should be included.

The problems are related to poor visibility and changing wind directions.

When an advancing fire threatens dwellings, the inhabitants may have to be evacuated. This presents an opportunity for thieves and vandals, and calls for diligent policing activities.

The most dangerous work task is the making of backfires: hurriedly cutting through the trees and underbrush to form a path parallel to the advancing line of fire and setting it afire at just the right moment to produce a strong draught of air heading toward the advancing fire, so that the two fires meet. The draught from the advancing fire is caused by the need of the advancing fire to pull oxygen from all sides of the fire. It is very clear that if the timing fails, then the whole crew will be engulfed by strong smoke and exhausting heat and then will suffer a lack of oxygen. Only the most experienced people should set backfires, and they should prepare escape routes in advance to either side of the fire. This backfiring system should always be practised in advance of the fire season; this practice should include the use of equipment like torches for lighting the backfire. Ordinary matches are too slow!

As a last effort for self-preservation, a firefighter can scrape all burning materials in a 5 m diameter, dig a pit in the centre, cover him or herself with soil, soak headgear or jacket and put it over his or her head. Oxygen is often available only at 1 to 2 centimetres from ground level.

Water bombing by aircraft

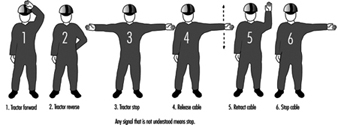

The use of aircraft for fighting fires is not new (the dangers in aviation are described elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia). There are, however, some activities that are very dangerous for the ground crew in a forest fire. The first is related to the official sign language used in aircraft operations—this has to be practised during training.

The second is how to mark all areas where the aircraft is going to load water for its tanks. To make this operation as safe as possible, these areas should be marked off with floating buoys to obviate the pilot’s need to use guesswork.

The third important matter is to keep constant radio contact between the ground crew and the aircraft as it prepares to release its water. The release from small heli-buckets of 500 to 800 litres is not that dangerous. Large helicopters, however, like the MI-6, carry 2,500 litres, while the C-120 aircraft takes 8,000 litres and the IL-76 can drop 42,000 litres in one sweep. If, by chance, one of these big loads of water lands on crew members on the ground, the impact could kill them.

Training and organization

One essential requirement in firefighting is to line up all firefighters, villagers and forest workers to organize joint firefighting exercises before the beginning of fire season. This is the best way to secure successful and safe firefighting. At the same time, all the work functions of the various levels of command should be practised in the field.

The selected fire chief and leaders should be the ones with the best knowledge of local conditions and of government and private organizations. It is obviously dangerous to assign somebody either too high up the hierarchy (no local knowledge) or too low down the hierarchy (often lacking authority).

Tree Planting

Tree planting consists of putting seedlings or young trees into the soil. It is mainly done to re-grow a new forest after harvesting, to establish a woodlot or to change the use of a piece of land (e.g., from a pasture to a woodlot or to control erosion on a steep slope). Planting projects can amount to several million plants. Projects may be executed by the forest owners’ private contractors, pulp and paper companies, the government’s forest service, non-governmental organizations or cooperatives. In some countries, tree planting has become a veritable industry. Excluded here is the planting of large individual trees, which is considered more the domain of landscaping than forestry.

The workforce includes the actual tree planters as well as tree nursery staff, workers involved in transporting and maintaining the plants, support and logistics (e.g., managing, cooking, driving and maintaining vehicles and so on) and quality control inspectors. Women comprise 10 to 15% of the tree-planter workforce. As an indication of the importance of the industry and the scale of activities in regions where forestry is of economic importance, the provincial government in Quebec, Canada, set an objective of planting 250 million seedlings in 1988.

Planting Stock

Several technologies are available to produce seedlings or small trees, and the ergonomics of tree planting will vary accordingly. Tree planting on flat land can be done by planting machines. The role of the worker is then limited to feeding the machine manually or merely to controlling quality. In most countries and situations, however, site preparation may be mechanized, but actual planting is still done manually.

In most reforestation, following a forest fire or clear cutting, for example, or in afforestation, seedlings varying from 25 to 50 cm in height are used. The seedlings are either bare-rooted or have been grown in containers. The most common containers in tropical countries are 600 to 1,000 cm3. Containers may be arranged in plastic or styrofoam trays which usually hold from 40 to 70 identical units. For some purposes, larger plants, 80 to 200 cm, may be needed. They are usually bare-rooted.

Tree planting is seasonal because it depends on rainy and/or cool weather. The season lasts 30 to 90 days in most regions. Although it may seem a lesser seasonal occupation, tree planting must be considered a major long-term strategic activity, both for the environment and for revenue where forestry is an important industry.

Information presented here is based mainly on the Canadian experience, but many of the issues can be extrapolated to other countries with a similar geographical and economic context. Specific practices and health and safety considerations for developing countries are also addressed.

Planting Strategy

Careful evaluation of the site is important for setting adequate planting targets. A superficial approach can hide field difficulties that will slow down the planting and overburden the planters. Several strategies exist for planting large areas. One common approach is to have a team of 10 to 15 planters equally spaced in a row, who progress at the same pace; a designated worker then has the task of bringing in enough seedlings for the whole team, usually by means of small off-road vehicles. One other common method is to work with several pairs of planters, each pair being responsible for fetching and carrying their own small stock of plants. Experienced planters will know how to space out their stock to avoid losing time carrying plants back and forth. Planting alone is not recommended.

Seedling Transport

Planting relies on the steady supply of seedlings to the planters. They are brought in several thousands at a time from the nurseries, on trucks or pick-ups as far as the road will go. The seedlings must be unloaded rapidly and watered regularly. Modified logging machinery or small off-road vehicles can be used to carry the seedlings from the main depot to the planting sites. Where seedlings have to be carried by workers, such as in many developing countries, the workload is very heavy. Suitable back-packs should be used to reduce fatigue and risk of injuries. Individual planters will carry from four to six trays to their respective lots. Since most planters are paid at a piece rate, it is important for them to minimize unproductive time spent travelling, or fetching or carrying seedlings.

Equipment and Tools

The typical equipment carried by a tree planter includes a planting shovel or a dibble (a slightly conical metal cylinder at the end of a stick, used to make holes closely fitting the dimensions of containerized seedlings), two or three plant container trays carried by a harness, and safety equipment such as toe-capped boots and protective gloves. When planting bare-rooted seedlings, a pail containing enough water to cover the seedling’s roots is used instead of the harness, and is carried by hand. Various types of tree-planting hoes are also widely used for bare-rooted seedlings in Europe and North America. Some planting tools are manufactured by specialized tool companies, but many are made in local shops or are intended for gardening and agriculture, and present some design deficiencies such as excess weight and improper length. The weight typically carried is presented in table 1.

Table 1. Typical load carried while planting.

|

Element |

Weight in kg |

|

Commercially available harness |

2.1 |

|

Three 45-seedling container trays, full |

12.3 |

|

Typical planting tool (dibble) |

2.4 |

|

Total |

16.8 |

Planting Cycle

One tree-planting cycle is defined as the series of steps necessary to put one seedling into the ground. Site conditions, such as slope, soil and ground cover, have a strong influence on productivity. In Canada the production of a planter can vary from 600 plants per day for a novice to 3,000 plants per day for an experienced individual. The cycle may be subdivided as follows:

Selection of a micro-site. This step is fundamental for the survival of the young trees and depends on several criteria taken into account by quality control inspectors, including distance from preceding plant and natural offspring, closeness to organic material, absence of surrounding debris and avoidance of dry or flooded spots. All these criteria must be applied by the planter for each and every tree planted, since their non-observance can lead to a financial penalty.