Health in the Third Age: Pre-retirement Programmes

It is increasingly being recognized that the last third of life—the “third age”—requires as much thought and planning as do education and training (the “first age”) and career development and retraining (the “second age”). About 30 years ago, when the movement to address the needs of the retired began, the average male employee in the United Kingdom, and in many other developed countries as well, retired at the age of 65 as a rather worn-out worker with a limited life expectancy and, especially if he was a blue collar worker or labourer, with an inadequate pension or none at all.

This scene has been changing dramatically. Many people are retiring younger, voluntarily or at ages other than those dictated by mandatory retirement regulations; for some, early retirement is being forced upon them by illness and disability and by redundancy. At the same time, many others are electing to continue to work long past the “normal” retirement age, in the same job or in another career.

By and large, today’s retirees generally have better health and longer life expectancies. Indeed, in the United Kingdom, the over-80s are the fastest growing group in the population, while more and more people are living into their 90s. And with the surge of women into the workforce, a growing number of the retirees is female, many of whom, owing to longer life expectancies than their male counterparts, will be single or widowed.

For a time—two decades or longer for some—most retirees retain mobility, vigour and functional capacities honed by experience. Thanks to higher living standards and advances in medical care, this period continues to extend. Sadly, however, many live longer than their biological structures were designed for (i.e., some of their bodily systems give up efficient service while the rest struggle on), causing increasing medical and social dependency with ever fewer compensatory enjoyments. The goal of retirement planning is to enhance and extend enjoyment of the period of well-being and ensure to the extent possible the resources and support systems needed during the final decline. It goes beyond estate planning and the disposition of property and assets, although these are often important elements.

Thus, retirement today can offer immeasurable compensations and benefits. Those who retire in good health can expect to live another 20 to 30 years, enjoying potentially purposeful activity for at least two-thirds of this period. This is far too long to drift about doing nothing in particular or rotting away on some sunny “Costa Geriatrica”. And their ranks are being swelled by those who retire early by choice or, sadly, because of redundancy, and by women, too, more of whom are retiring as adequately pensioned workers expecting to remain purposefully active rather than to live as dependants.

Fifty years ago, pensions were inadequate and economic survival was a struggle for most of the elderly. Now, employer-provided pensions and general welfare benefits supplied by government agencies, although still inadequate for many, do allow a not too unreasonable existence. And, because the skilled workforce is shrinking in many industries while employers are recognizing that older workers are productive and often more reliable employees, opportunities for third-agers to get part-time employment are improving.

Further, the “retired” now form about a third of the population. Being sound in mind and limb, they are an important and potentially contributory segment of society which, as they recognize their importance and potential, can organize themselves to pull much more weight. An example in the United States is the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), which offers to its 33 million members (not all of whom are retired, since membership in the AARP is open to anyone aged 50 or over) a broad range of benefits and exercises considerable political influence. At the first Annual General Meeting of the United Kingdom’s Pre-Retirement Association (PRA) in 1964, Lord Houghton, its president, a member of the Cabinet, said, “If only pensioners could get their act together, they could swing an election.” This has not yet happened, and probably never will in these terms, but it is now accepted in most developed countries that there is a “third age”, comprising a third of the population that has both expectations and needs along with an enormous potential for contributing to the benefit of its members and to the community as a whole.

And with this acceptance, there has been a growing realization that adequate provision and opportunity for this group is vital to social stability. Over the last few decades, politicians and governments have begun to respond through extension and improvement of the variety of “social security” and other welfare programmes. These responses have been handicapped both by fiscal exigencies and by bureaucratic rigidities.

Another, major, handicap has been the attitude of the pensioners themselves. Too many have accepted the stereotyped personal and social image of retirement as both the end of recognition as a useful or even deserving member of society and the expectation of being shunted into a backwater where one can be conveniently forgotten. Overcoming this negative image has been, and to a degree still is, the main objective of training for retirement.

As more and more retirees accomplished this transformation and looked to fulfil the needs that emerged, they became aware of the shortcomings of government programmes and began to look to employers to fill the gap. Thanks to accumulated savings and employer-provided pension programmes (many of which were shaped through collective bargaining with unions), they discovered financial resources that were often considerable. To enhance the value of their private pension schemes, employers and unions began to arrange for (and even offer) programmes providing advice and support in managing them.

In the United Kingdom, credit for this is largely due to the Pre-Retirement Association (PRA) which, with government support through the Department of Education (initially, this programme was shunted among the Departments of Health, Employment, and Education), is being accepted as the mainstream of retirement preparation.

And, as the thirst for such guidance and assistance has grown, a veritable industry of voluntary and for-profit organizations has come into existence to meet the demand. Some function quite altruistically; others are self-serving, and include insurance companies that wish to sell annuities and other insurance, investment firms that manage accumulated savings and pension income, real estate brokers selling retirement homes, operators of retirement communities seeking to sell memberships, charities that offer advice on the tax benefits of making contributions and bequests, and so on. These are supplemented by an army of publishers offering “how-to” books, magazines, audiotapes and videotapes, and by colleges and adult education organizations that offer seminars and courses on relevant topics.

While many of these providers focus primarily on coping with financial, social or family problems, recognition that well-being and productive living are dependent on being healthy has led to the increasing prominence of health education and health promotion programmes intended to avert, defer or minimize illness and disability. This is particularly the case in the United States, where employers’ financial commitment for the escalating costs of health care for retirees and their dependants has not only become a very weighty burden but now must be projected as a liability on the balance sheets included in corporation annual reports.

Indeed, some of the categorical voluntary health organizations (e.g., heart, cancer, diabetes, arthritis) produce educational materials specifically designed for employees approaching retirement age.

In short, the third age has arrived. Pre-retirement and retirement programmes offer opportunities both for maximizing personal and social well-being and function and for providing the necessary understanding, training and support.

Role of the Employer

Although far from universal, the main support and funding for pre-retirement programmes has come from employers (including local and central governments and the armed forces). In the United Kingdom, this was in large part due to the efforts of the PRA, which, early on, initiated company membership through which employees are provided with encouragement, advice and in-house courses. It has, in fact, not been difficult to convince commerce and industry that they have a responsibility far beyond the mere provision of pensions. Even there, as pension schemes and their tax implications have become more complicated, detailed explanations and personalized advice have become more important.

The workplace provides a convenient captive audience, making the presentation of programmes more efficient and less costly, while peer pressure enhances employee participation. The benefits to the employees and their dependants are obvious. The benefits to the employers are substantial, albeit more subtle: improved morale, the enhancement of the company’s image as a desirable employer, encouragement for retaining older employees with valuable experience, and retaining the good will of retirees, many of whom, thanks to profit-sharing and company-sponsored investment plans, are also shareholders. When workforce reductions are desired, employer-sponsored pre-retirement programmes are often presented to enhance the attractiveness of the “golden handshake,” a package of inducements for those accepting early retirement.

Similar benefits accrue to trade unions who offer such programmes as an adjunct to union-sponsored pension programmes: making union membership more attractive and enhancing good will and esprit de corps among union members. It should be noted that interest among the trade unions in the United Kingdom is only beginning to develop, primarily among the smaller and professional unions, like that of the airline pilots.

The employer may contract for a complete, “pre-packaged” programme or assemble one from the list of individual elements offered by organizations like the PRA, assorted adult educational institutions and the many investment, pension and insurance firms that offer retirement training courses as a commercial venture. Although generally of a high standard, the latter have to be monitored to be sure that they provide straightforward, objective information rather than promotion of the provider’s own products and services. The employer’s departments of personnel, pension and, where there is one, education, should be involved in assembling and presenting the programme.

The programmes may be given entirely in-house or at a conveniently located facility in the community. Some employers offer them during working hours but, more often, they are made available during lunch periods or after hours. The latter are more popular because they minimize interference with work schedules and they facilitate the attendance of spouses.

Some employers cover the entire cost of participation; others share it with the employees while some rebate all or part of the employee’s share on successful completion of the programme. While faculty should be available for answers to questions, participants are usually referred to appropriate experts when individualized personal consultations are needed. As a rule, these participants accept responsibility for any costs that may be required; sometimes, when the expert is affiliated with the programme, the employer may be able to negotiate reduced fees.

Pre-retirement Course

Philosophy

For many people, especially those who have been workaholics, separation from work is a wrenching experience. Work provides status, identity and association with other people. In many societies, we tend to be identified and to identify ourselves socially by the jobs we do. The work context that we are in, especially as we grow older, dominates our lives in terms of what we do, where we go and, particularly for professional people, our daily priorities. Separation from co-workers, and a sometimes unhealthy level of preoccupation with minor family and household affairs, indicate a need for developing a new frame of social reference.

Well-being and survival in retirement depend on understanding these changes and setting out to make the most of the opportunities they present. Central to such understanding is the concept of maintenance of health in the widest sense of the World Health Organization definition and a more modern acceptance of a holistic approach to medical problems. Establishment of and adherence to a healthful life style must be supplemented by properly managing finances, housing, activities and social relationships. Preserving financial resources for the time when increasing disability requires special care and assistance that may increase the cost of living is often more important than estate planning.

Organized courses which provide information and guidance may be considered the keystone of pre-retirement training. It is sensible for the course organizers to realize that the aim is not to provide all the answers but to delineate possible problem areas and point the way to the best solutions for each individual.

Topic areas

Pre-retirement programmes may include a variety of elements; the following briefly described topics are the most fundamental and should be assured a place among any programme’s discussions:

Vital statistics and demography.

Life expectancies at relevant ages—women live longer than men—and trends in family composition and their implications.

Understanding retirement.

The lifestyle, motivational and opportunity-based changes to be required over the next 20 to 30 years.

Health maintenance.

Understanding the physical and mental aspects of ageing and elements of the lifestyle that will promote optimal well-being and functional capacity (e.g., physical activity, diet and weight control, coping with failing vision and hearing, increased sensitivity to cold and hot weather, and use of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs). Discussions of this topic should include dealing with doctors and the health care system, periodic health screening and preventive interventions, and attitudes toward illness and disability.

Financial planning.

Understanding the company’s pension plan as well as potential social security and welfare benefits; managing investments to preserve resources and maximize income, including the investment of lump sum payments; managing home ownership and other properties, mortgages, and so on; continuation of employer/union-sponsored and other health insurance, including consideration of long-term care insurance, if available; how to select a financial advisor.

Domestic planning.

Estate planning and making a will; executing a living will (i.e., the setting forth of “medical directives” or naming a health care proxy) containing wishes about what treatments should or should not be administered in the event of potentially terminal illness and inability to participate in decision-making; relationships with spouse, children, grandchildren; coping with constriction of social contacts; role reversal in which the wife continues a career or outside activities while the husband takes more responsibility for cooking and homemaking.

Housing.

Home and garden may become too large, costly and burdensome as financial and physical resources shrink, or it may be too small as the retiree recreates an office or workshop in the home; with both spouses at home, it is helpful, if possible, to arrange for each to have his and her own territory to provide a modicum of privacy for activities and reflection; consideration of moving to another area or country or to a retirement community; availability of public transportation if automobile driving becomes imprudent or impossible; preparing for eventual frailty; assistance with homemaking and social contacts for the single person.

Possible activities.

How to find opportunities and training for new jobs, hobbies and volunteer activities; educational activities (e.g., completion of interrupted diploma and degree courses); travel (in the United States, Elderhostel, a voluntary organization, offers a large catalogue of year-round one-week or two-week adult education courses given at college campuses and vacation resorts throughout the United States and internationally).

Time management.

Developing a schedule of meaningful and enjoyable activities that balance individual and joint involvement; while new opportunities for “togetherness” are a benefit of retirement, it is important to realize the value of independent activities and to avoid “getting in each other’s way”; group activities including clubs, church and community organizations; recognizing the motivational value of ongoing paid or voluntary work commitments.

Organizing the course

The type, content and length of the course are usually determined by the sponsor on the basis of the available resources and expected costs, as well as the level of commitment and the interests of employee participants. Few courses will be able to cover all of the above topic areas in exhaustive detail, but the course should include some discussion of most (and preferably all) of them.

The ideal course, educators tell us, is of the day-release type (employees attend the course on company time) with about ten sessions in which participants can get to know each other and instructors can explore individual needs and concerns. Few companies can afford this luxury, but Pre-Retirement Associations (of which the United Kingdom has a network) and adult education centres run them successfully. The course may be presented as a short-term entity—as a two-day course which allows participants more discussion and more time for guidance in activities is probably the best compromise, rather than as a one-day course in which condensation requires more didactic than participative presentations—or it may involve a series of more or less brief sessions.

Who attends?

It is prudent that the course be open to spouses and partners; this may influence its location and timing.

Clearly, every employee facing retirement should be given the opportunity to attend, but the problem is the mix. Senior executives have very different attitudes, aspirations, experiences and resources than relatively junior executives and line staff. Widely differing educational and social backgrounds may inhibit the free-wheeling exchanges that make the courses so valuable to participants, particularly with respect to finances and post-retirement activities. Very large classes dictate a more didactic approach; groups of 10 to 20 facilitate valuable exchanges of concerns and experiences.

Employees in large companies which emphasize corporate identity, like IBM in the United States and Marks & Spencer in the United Kingdom, often find it difficult to fit into the wide world without the “big brother” aura to support them. This is particularly true of the separate services in the armed forces, at least in the United Kingdom and the United States. At the same time in such tightly-knit groups, employees sometimes find it difficult to express concerns that might be construed as company disloyalty. This does not appear as much of a problem when courses are given off-site or include employees of number of companies, a necessity when smaller organizations are involved. These “mixed” groups are often less formal and more productive.

Who teaches?

It is essential that the instructors have the knowledge and, especially, the communication skills required to make the course a useful and pleasurable experience. While the company’s personnel, medical and education departments may be involved, qualified consultants or academicians are often considered to be more objective. In some instances, qualified instructors recruited from among the company’s retirees can combine greater objectivity with knowledge of the company environment and culture. Since it is rare for any one individual to be expert in all of the issues involved, a course director supplemented by several specialists is usually desirable.

Supplemental materials

The course sessions are usually supplemented by workbooks, videotapes and other publications. Many programmes include subscriptions to pertinent books, periodicals, and newsletters, which are most effective when addressed to the home, where they may be shared by spouses and family members. Membership in national organizations, like PRA and AARP or their local counterparts, provides access to useful meetings and publications.

When is the course given?

Pre-retirement programmes generally begin about five years before the scheduled retirement date (recall that AARP membership becomes available at age 50, regardless of planned retirement age). In some companies, the course is repeated every one or two years, with employees invited to take it as often as they wish; in others, the curriculum is divided into segments given in successive years to the same group of participants with content varying as the retirement date approaches.

Course evaluation

The number of eligible employees electing to participate and the rate of drop-out are perhaps the best indicators of the utility of the course. However, a mechanism should be introduced so that participants can feed back their impressions of the course content and the quality of the instructors as a basis for making changes.

Caveats

Courses with uninspired presentations of largely irrelevant material are not likely to be very successful. Some employers use questionnaire surveys or conduct focus groups to probe the interests of potential participants.

An important point in the decision-making process is the state of employer/employee relations. When hostility is overt or just beneath the surface, employees are not likely to assign great value to anything the employer offers, especially if it is labelled “for your own good”. Employee acceptance can be enhanced by having one or more staff committees or union representatives involved in the design and planning.

Finally, as retirement approaches and becomes a way of life, circumstances change and new problems arise. Accordingly, periodic repetition of the course should be planned, both for those who might benefit from a rerun and those who are newly approaching the “third age”.

Post-retirement Activities

Many companies continue contact with retirees throughout their lives, often together with their surviving spouses, especially when employer-sponsored health insurance is continued. Periodic health screenings and health education and promotion programmes designed for “seniors” are provided and, when needed, access to individual consultations on health, financial, domestic and social problems is made available. An increasing number of larger companies subsidize pensioner clubs which may have more or less autonomy in programming.

Some employers make a point of rehiring retirees on a temporary or part-time basis when extra help is needed. Other examples from New York City include: the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States, which encourages retirees to volunteer their services to non-profit-making community agencies and educational institutions, paying them a modest stipend to offset commuting and incidental out-of-pocket expenses; the National Executive Service Corps, which arranges to provide the expertise of retired executives to companies and government agencies around the world; the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), which has instituted the “Friendly Visiting Program,” which trains retirees to provide companionship and useful services to members beset by problems of ageing. Similar activities are sponsored by pensioner clubs in the United Kingdom.

Except for employer/union-sponsored pensioner clubs, most post-retirement programmes are carried out by adult education organizations through their offerings of formal courses. In the United Kingdom, there are several nationwide pensioner groups like PROBUS which holds regular local meetings to provide information and social contacts to their members, and the PRA which offers individual and corporate membership for information, courses, tutors and general advice.

An interesting development in the United Kingdom, based on a similar organization in France, is the University of the Third Age, which is centrally coordinated with local groups in the larger towns. Its members, mostly professionals and academics, work to broaden their interests and extend their knowledge.

Through their regular intramural publications as well as in materials specifically prepared for retirees, many companies and unions provide information and advice, often spiced with anecdotes about retirees’ activities and experiences. Most developed countries have at least one or two general circulation magazines aimed at retirees: France’s Notre Temps has a large circulation among third agers and, in the United States, AARP’s Modern Maturity goes to its more than 33 million members. In the UK there are two monthly publications for the retired: Choice and SAGA Magazine. The European Commission is currently sponsoring a multi-language retirement workbook, Making the Most of Your Retirement.

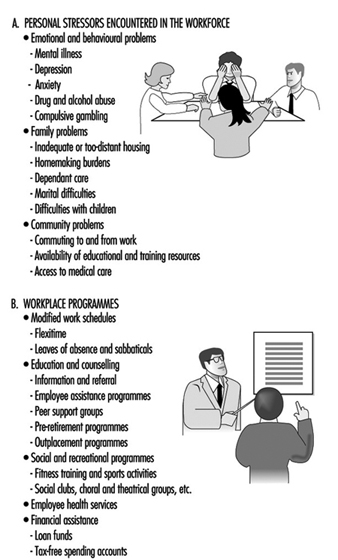

Eldercare

In the many developed countries, employers are becoming increasingly aware of the impact of the problems faced by employees with elderly or disabled parents, in-laws and grandparents. Although some of these may be pensioners of other companies, their needs for support, attention, and direct services may be significant burdens for the employees who must contend with their own jobs and personal affairs. To ease those burdens and reduce the consequent distraction, fatigue, absenteeism and lost productivity, employers are offering “eldercare programmes” to these caregivers (Barr, Johnson and Warshaw 1992; US General Accounting Office 1994). These provide various combinations of education, information and referral programmes, modified work schedules and respite leaves, social support, and financial aid.

Conclusion

It is abundantly clear that demographic and social workforce trends in the developed countries are producing increasing awareness of the need for information, training and advice across the whole spectrum of “third age” problems. This awareness is being appreciated by employers and labour unions—and by politicians, as well—and is being translated into pre-retirement programmes and post-retirement activities which offer potentially great benefits to the ageing, their employers and unions, and society at large.

Employee Assistance Programmes

Introduction

Employers may recruit workers and trade unions may enlist members, but both get human beings who bring to the workplace all the concerns, problems and dreams characteristic of the human condition. As the world of work has become increasingly conscious that the competitive edge in a global economy depends on the productivity of its work force, the key agents in the workplace—management and labour unions—have devoted significant attention to meeting the needs of those human beings. Employee Assistance Programmes (EAPs), and their parallel in unions, Membership Assistance Programmes (MAPs) (hereafter referred to jointly as EAPs), have developed in workplaces around the world. They constitute a strategic response to meeting the diverse needs of a working population and, more recently, to meeting the humanist agenda of organizations of which they are a part. This article will describe the origins, functions and organization of EAPs. It is written from the point of view of the social worker’s profession, which is the major profession driving this development in the United States and one which, because of its worldwide interconnections, appears to be playing a major role in establishing EAPs worldwide.

The extent of development of employee assistance programmes varies from country to country, reflecting, as David Bargal has pointed out (Bargal 1993), the differences in degree of industrialization, state of the professional training available for appropriate personnel, degree of unionization in the employment sector and societal commitment to social issues, among other variables. His comparison of EAP development in Australia, the Netherlands, Germany and Israel leads him to suggest that although industrialization may be a necessary condition to achieve a high rate of EAPs and MAPs in a country’s workplaces, it may not be sufficient. The existence of these programmes also is characteristic of a society with significant unionization, labour/management cooperation and a well-developed social service sector in which government plays a major role. Further, there is need for a professional culture, supported by an academic specialization that promotes and disseminates social services at the workplace. Bargal concludes that the greater the aggregate of these characteristics in a given nation, the more likely that there will be extensive availability of EAP services in its workplaces.

Diversity is also apparent among programmes within individual countries in relation to structure, staffing, focus and scope of programme. All EAP efforts, however, reflect a common theme. The parties in the workplace seek to provide services to remediate the problems that employees experience, often without causal relationship to their work, that interfere with employees’ productivity on the job and sometimes with their general well-being as well. Observers have noted an evolution in EAP activities. Although the initial impetus may be the control of alcoholism or drug abuse among workers, nevertheless, over time, interest in individual workers becomes more broadly based, and the workers themselves become only one element in a dual focus that embraces the organization as well.

This organizational focus reflects an understanding that many workers are “at risk” of being unable to maintain their work roles and that the “risk” is as much a function of the way the work world is organized as it is a reflection of the individual characteristics of any particular worker. For example, ageing workers are “at risk” if the workplace technology changes and they are denied retraining because of their age. Single parents and caretakers of the elderly are “at risk” if their work environment is so rigid that it does not provide time flexibility in the face of the illness of a dependant. A person with a disability is “at risk” when a job changes and accommodations are not offered to enable the individual to perform in keeping with the new requirements. Many other examples will occur to the reader. What is significant is that, in the matrix of being able to change the individual, the environment, or some combination thereof, it has become increasingly clear that a productive, economically successful work organization cannot be achieved without consideration of the interaction between organization and individual at a policy level.

Social work rests on a model of individual in environment. The evolving definition of “at risk” has enhanced the potential contribution of its practitioners. As Googins and Davidson have noted, the EAP is exposed to a range of problems and issues affecting not only individuals, but also families, the corporation and the communities in which they are located (Googins and Davidson 1993). When a social worker with an organizational and environmental outlook functions in the EAP, that professional is in a unique position to conceptualize interventions that promote not only the EAP’s role in delivery of individual service but in advising on organizational policy in the workplace as well.

History of EAP Development

The origin of social service delivery at the workplace dates back to the time of industrialization. In the craft workshops that marked an earlier period, work groups were small. Intimate relationships existed between the master craftsman and his journeymen and apprentices. The first factories introduced larger work groups and impersonal relationships between employer and employee. As problems that interfered with the workers’ performance became apparent, employers began to provide helping individuals, often called social or welfare secretaries, to assist workers recruited from rural settings, and sometimes new immigrants, with the process of adjusting to formalized workplaces.

This focus on using social workers and other human service providers to achieve acculturation of new populations to the demands of factory labour continues internationally to this day. Several nations, for example Peru and India, legally require that work settings that exceed a particular employment level provide a human service worker to be available to replace the traditional support structure that was left behind in the home or rural environment. These professionals are expected to respond to the needs presented by the newly recruited, largely displaced rural residents in relation to concerns of everyday living such as housing and nutrition as well as those involving illness, industrial accidents, death and burial.

As the challenges involved in maintaining a productive work force evolved, a different set of issues asserted itself, warranting a somewhat different approach. EAPs probably represent a discontinuity from the earlier welfare secretary model in that they are more clearly a programmatic response to the problems of alcoholism. Pressed by the need to maximize productivity during the Second World War, employers “attacked” the losses resulting from alcohol abuse among workers by establishing occupational alcoholism programmes in the major production centres of the Western Allies. The lessons learned from the effective efforts at containing alcoholism, and the concomitant improvement in the productivity of the workers involved, received recognition after the War. Since that time, there has been a slow but steady increase in service delivery programmes worldwide that make use of the employment site as an appropriate location and centre of support for remediating problems that are identified as causes of major drains in productivity.

This trend has been aided by the development of multinational corporations that tend to replicate an effective effort, or a legally required system, in all their corporate units. They have done so almost without regard to the programme’s relevance or cultural appropriateness to the particular country in which the unit is located. For example, South African EAPs resemble those in the United States, a state of affairs accountable in part by the fact that the earliest EAPs were established in the local outposts of multinational corporations that are headquartered in the United States. This cultural crossover has been positive in that it has fostered replication of the best of each country on a worldwide scale. An example is the sort of preventive action, in relation to sexual harassment or labour force diversity issues that have come to prominence in the United States, that has become the standard to which American corporate units around the world are expected to adhere. These provide models for some local firms to establish comparable initiatives.

Rationale for EAPs

EAPs may be differentiated by their stage of development, programme philosophy or definition of what problems are appropriate to address and what services are acceptable responses. Most observers would agree, however, that these occupational interventions are expanding in scope in the countries that have already established such services, and are incipient in those nations that have yet to establish such initiatives. As already indicated, one reason for expansion can be traced to the widespread understanding that drug and alcohol abuse in the workplace is a significant problem, costing lost time and high medical care expenses and seriously interfering with productivity.

But EAPs have grown in response to a wide array of changing conditions that cross national boundaries. Unions, pressed to offer benefits to maintain the loyalty of their members, have viewed EAPs as a welcome service. Legislation on affirmative action, family leave, worker’s compensation and welfare reform all involve the workplace in a human service outlook. The empowerment of working populations and the search for gender equity that are needed for employees to function effectively in the team environment of the modern production machine, are aims that are well served by the availability of destigmatized, universal social service delivery systems that can be established in the world of work. Such systems also help with the recruitment and retention of a quality labour force. EAPs have also filled the gap in community services that exists, and seems to be increasing, in many nations of the world. The spread of, and desire to contain HIV/AIDS, as well as the growing interest in prevention, wellness and safety in general, have each contributed support to the educational role of EAPs in the world’s workplaces.

EAPs have proven a valuable resource in helping workplaces respond to the pressure of demographic trends. Such changes as the increase in single parenthood, in the employment of mothers (whether of infants or of young children), and in the number of two-worker families have required attention. The ageing of the population and the interest in reducing welfare dependency through maternal employment—facts that are apparent in most industrialized countries—have involved the workplace in roles that require assistance from human service providers. And, of course, the ongoing problem of drug and alcohol abuse that has reached epidemic proportions in many countries, has been a major concern of work organizations. A survey examining public perception of the drug crisis in 1994 as compared with five years earlier found that 50% of respondents felt it was much greater, an additional 20% felt it was somewhat greater, only 24% considered it the same and the remaining 6% felt it had declined. While each of these trends varies from country to country, all exist across countries. Most are characteristic of the industrialized world where EAPs have already developed. Many can be observed in the developing countries that are experiencing any significant degree of industrialization.

Functions of EAPs

The establishment of an EAP is an organizational decision that represents a challenge to the existing system. It suggests that the workplace has not attended adequately to the needs of individuals. It confirms the mandate for employers and trade unions, in their own organizational interest, to respond to the broad social forces at work in society. It is an opportunity for organizational change. Though resistance may occur, as it does in all situations where systemic change is attempted, the trends described earlier provide many reasons why EAPs can be successful in their quest for offering both counselling and advocacy services to individuals and policy advice to the organization.

The kinds of functions EAPs serve reflect the presenting issues to which they seek to respond. Probably every programme extant deals with drug and alcohol abuse. Interventions in this connection usually include assessment, referral, training for supervisors and operation of support groups to maintain employment and encourage abstinence. The service agenda of most EAPs, however, is more broadranging. Programmes offer counselling to those experiencing marital problems or difficulties with children, those needing help with finding day care or those making decisions concerning elder care for a family member. Some EAPs have been asked to deal with work environment issues. Their response is to give help to families adjusting to relocation, to bank employees who experience robberies and need trauma debriefing, to disaster crews, or to health care workers accidentally exposed to HIV infection. Assistance in coping with “downsizing” is supplied, too, to both those laid off and the survivors of such lay-offs. EAPs may be called on to assist with organizational change to meet affirmative action goals or to serve as case managers in achieving accommodation and return to work for employees who become disabled. EAPs have been enlisted in preventive activities as well, including good nutrition and smoking cessation programmes, encouraging participation in exercise regimes or other parts of health promotion efforts, and offering educational initiatives that can range from parenting programmes to preparation for retirement.

Although these EAP responses are multifaceted, they typify EAPs as widespread as Hong Kong and Ireland. Studying a non-random sample of American employers, trade unions and contractors who deliver EAP drug and alcohol abuse services, for example, Akabas and Hanson (1991) found that plans in a variety of industries, with different histories and under various auspices, all conform to each other in important ways. The researchers, expecting that there would be a wide variety of creative responses to dealing with workplace needs, identified, on the contrary, an astounding uniformity of programme and practice. At an International Labour Organization (ILO) international conference convoked in Washington, D.C. to compare national initiatives, a similar degree of uniformity was confirmed throughout western Europe (Akabas and Hanson 1991).

Respondents in the surveyed work organizations in the United States agreed that legislation has had a significant impact on determining the components of their programmes and the rights and expectations of client populations. In general, programmes are staffed by professionals, more often social workers than professionals of any other discipline. They respond to a broad constituency of workers, and often their family members, with services that provide diverse care for a range of presenting problems in addition to their focus on rehabilitation of alcohol and drug abusers. Most programmes overcome general inattention by top management and inadequate training for and support from supervisors, to achieve penetration rates of between 3 and 5% of the total workers at the target site. The professionals who staff the EAP and MAP movements seem to agree that confidentiality and trust are the keys to effective service. They claim success in dealing with the problems of drug and alcohol abuse although they can point to few evaluative studies to confirm the efficacy of their intervention in relation to any aspect of service delivery.

Estimates suggest that there are as many as 10,000 EAPs now in operation in settings throughout the United States alone. Two main types of service delivery systems have evolved, the one directed by an inhouse staff and the other provided by an outside contractor that offers service to numerous work organizations (employers and trade unions) at the same time. There is a raging debate as to the relative merits of internal versus external programmes. Claims of increased protection of confidentiality, greater diversity of staff and clarity of role undiluted by other activities, are made for external programmes. Advocates of internal programmes point to the advantage conferred by their position within the organization with respect to effective intervention at the systems level and to the policy-making influence that they have gained as a result of their organizational knowledge and involvement. Since organization-wide initiatives are increasingly valued, internal programmes are probably better for those worksites that have sufficient demand (at least 1,000 employees) to warrant a full-time staffer. This arrangement allows, as Googins and Davidson (1993) point out, improved access to employees because of the varied services that can be offered and the opportunity it affords to exert influence on policymakers, and it facilitates collaboration and integration of the EAP function with others in the organization—all of these capabilities strengthen the authority and role of the EAP.

Work and Family Issues: A Case in Point

The interaction of EAPs, over time, with work and family issues provides an informative example of the evolution of EAPs and of their potential for individual and organizational impact. EAPs developed, historically speaking, parallel with the period during which women entered the labour market in increasing numbers, especially single mothers and mothers of infants and young children. These women often experienced tension between their family demands for dependant care—whether children or the elderly—and their job requirements in a work environment in which the roles of work and family were considered to be separate, and management was inhospitable to the need for flexibility with respect to work and family issues. Where there was an EAP, the women brought their problems to it. EAP staffers identified that women under stress became depressed and sometimes coped with this depression by drug and alcohol abuse. Early EAP responses involved counselling on drug and alcohol abuse, education about time management, and referral to child and elder care resources.

As the number of clients with similar presenting problems mounted, EAPs carried out needs assessments that pointed to the importance of moving from case to class, that is, they began to look for group rather than individual solutions, offering, for example, group sessions on coping with stress. But even this proved to be an inadequate approach to problem resolution. With an understanding that needs differ across the life cycle, EAPs began thinking about their client population in age-related cohorts that had different requirements. Young parents needed flexible leave to care for sick children and easy access to child care information. Those in their middle thirties to late forties were identified as the “sandwich generation”; at their time of life, the twofold demands of adolescent children and ageing relatives increased the need for an array of support services that included education, referral, leave, family counselling and abstinence assistance, among others. The mounting pressures experienced by ageing workers who face the onset of disability, the need to accommodate to a work world in which almost all one’s associates, including one’s supervisors, are younger than oneself, while planning for retirement and dealing with their frail elderly relatives (and sometimes with the parenting demands of the children of their children), create yet another set of burdens. The conclusion drawn from monitoring these individual needs and the service response to them was that what was required was a change in workplace culture that integrated the work and family lives of employees.

This evolution has led directly to the emergence of the EAP’s current role with respect to organizational change. During the process of meeting individual needs, it is probable that any given EAP has built up credibility within the system and is regarded by the key people as the source of knowledge about work and family issues. Likely, it has served an educational and informational role in response to questions raised by managers in numerous departments affected by the problems that occur when these two aspects of human life are experienced in conflict with each other. The EAP has probably collaborated with many organizational actors, including affirmative action officers, industrial relations experts, union representatives, training specialists, safety and health personnel, the medical department staff, risk managers and other human resource personnel, and fiscal workers, and line managers and supervisors.

A force field analysis, a technique suggested in the 1950s by Kurt Lewin (1951), provides a framework for defining the activities necessary to undertake to produce organizational change. The occupational health professional should understand where there will be support within the organization to resolve work and family issues on a systemic basis, and where there might be opposition to such a policy approach. A force field analysis should identify the key actors in the corporation, union or government agency who will influence change, and the analysis will summarize the promoting and restraining forces that will influence these actors in relation to work and family policy.

A sophisticated outcome of an organizational approach to work and family issues will have the EAP participating in a policy committee that establishes a statement of purpose for the organization. The policy should recognize the dual interests of its employees in being both productive workers and effective family participants. Expressed policy should indicate the organization’s commitment to establishing a flexible climate and work culture in which such dual roles can exist in harmony. Then an array of benefits and programmes may be specified to fulfil that commitment including, but not limited to, flexible work schedules, job sharing and part-time employment options, subsidized or onsite child care, an advice and referral service to assist with other child and eldercare needs, family leave with and without pay to cover demands deriving from illness of a relative, scholarships for children’s education and for employees’ own development, and individual counselling and group support systems for the variety of presenting problems experienced by family members. These manifold initiatives related to work and family issues would combine to allow a total individual and environmental response to the needs of workers and their work organizations.

Conclusions

There is ample experiential evidence to suggest that the provision of these benefits assists workers to their goal of productive employment. Yet these benefits have the potential to become costly programmes and they offer no guarantee that work will be performed in an effective and efficient manner as a result of their implementation. Like the EAPs that foster them, work and family benefits must be assessed for their contribution to the organization’s effectiveness as well as to the well-being of its many constituencies. The uniformity of development, described earlier, can be interpreted as support for the fundamental value of EAP services across work places, employers and nations. As the world of work becomes increasingly demanding in the era of a competitive global economy, and as the knowledge and skill that workers bring to the job becomes more important than their mere presence or physical strength, it seems safe to predict that EAPs will be called upon increasingly to provide guidance to organizations in fulfilling their humanist responsibilities to their employees or members. In such an individual and environmental approach to problem solving, it seems equally safe to predict that social workers will play a key role in service delivery.

Alcohol and Drug Abuse

Introduction

Throughout history human beings have sought to alter their thoughts, feelings and perceptions of reality. Mind-altering techniques, including reduction of sensory input, repetitive dancing, sleep deprivation, fasting and prolonged meditation have been employed in many cultures. However, the most popular method for producing mood and perception changes has been the use of mind-altering drugs. Of the 800,000 species of plants on earth, about 4,000 are known to produce psychoactive substances. Approximately 60 of these have been used consistently as stimulants or intoxicants (Malcolm 1971). Examples are coffee, tea, the opium poppy, coca leaf, tobacco and Indian hemp, as well as those plants from which beverage alcohol is fermented. In addition to naturally occurring substances, modern pharmaceutical research has produced a range of synthetic sedatives, opiates and tranquillizers. Both plant-derived and synthetic psychoactive drugs are commonly used for medical purposes. Several traditional substances are also employed in religious rites and as part of socialization and recreation. In addition, some cultures have incorporated drug use into customary workplace practices. Examples include the chewing of coca leaves by Peruvian Indians in the Andes and the smoking of cannabis by Jamaican sugar cane workers. The use of moderate amounts of alcohol during farm labour was an accepted practice in the past in some Western societies, for example in the United States in the eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century. More recently, it was customary (and even required by some unions) for employers of battery burners (workers who incinerate discarded storage batteries to salvage their lead content) and house painters using lead-based paints to provide each worker with a daily bottle of whisky to be sipped during the work day in the belief—an erroneous one—that it would prevent lead poisoning. In addition, drinking has been a traditional part of certain occupations, as, for example, among brewery and distillery salespeople. These sales representatives are expected to accept the hospitality of the tavern owner on completing their order-taking.

Customs that dictate alcohol use persist in other work too, such as the “three martini” business lunch, and the expectation that groups of workers will stop at the neighbourhood pub or tavern for a few convivial rounds of drinks at the end of the work day. This latter practice poses a particular hazard for those who then drive home.

Mild stimulants also remain in use in contemporary industrial settings, institutionalized as coffee and tea breaks. However, several historical factors have combined to make the use of psychoactive substances at the workplace a major social and economic problem in contemporary life. The first of these is the trend towards employing increasingly sophisticated technology in today’s workplace. Modern industry requires alertness, unimpaired reflexes and accurate perception on the part of workers. Impairments in these areas can cause serious accidents on one hand and can interfere with the accuracy and efficiency of work on the other. A second important trend is the development of more powerful psychoactive drugs and more rapid means of drug administration. Examples are the intranasal or intravenous administration of cocaine and the smoking of purified cocaine (“freebase” or “crack” cocaine). These methods, delivering much more powerful cocaine effects than the traditional chewing of coca leaves, have greatly increased the dangers of cocaine use on the job.

Effects of Alcohol and Other Drug Usein the Workplace

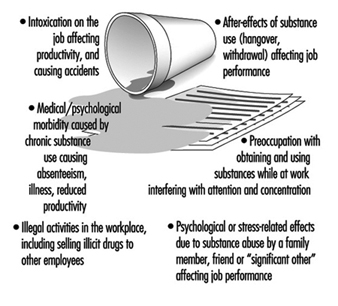

Figure 1 summarizes the various ways in which the use of psychoactive substances can influence the functioning of employees in the workplace. Intoxication (the acute effects of drug ingestion) is the most obvious hazard, accounting for a wide variety of industrial accidents, for example vehicle crashes due to alcohol-impaired driving. In addition, the impaired judgement, inattention and dulled reflexes produced by alcohol and other drugs also interferes with productivity at every level, from the board room to the production line. Furthermore, workplace impairment due to drug and alcohol use often lasts beyond the period of intoxication. The alcohol-related hangover may produce headache, nausea and photophobia (light sensitivity) for 24 to 48 hours after the last drink. Workers suffering from alcohol dependence may also undergo alcohol withdrawal symptoms on the job, with shaking, sweating and gastrointestinal disturbances. Heavy cocaine use is characteristically followed by a withdrawal period of depressed mood, low energy and apathy, all of which interfere with work. Both intoxication and the after-effects of drug and alcohol use also characteristically lead to lateness and absenteeism. In addition, the chronic use of psychoactive substances is implicated in a wide range of health problems that increase society’s medical costs and time lost from work. Cirrhosis of the liver, hepatitis, AIDS and clinical depression are examples of such problems.

Figure 1. Ways in which alcohol/drug use can cause problems in the workplace.

Workers who become heavy, frequent users of alcohol or other drugs (or both) may develop a dependency syndrome, which characteristically includes a preoccupation with obtaining the drug or the money needed to buy it. Even before other drug or alcohol-induced symptoms begin to interfere with work, this preoccupation may already have started to impair productivity. Furthermore, as a result of the need for money, the employee may resort to stealing items from the workplace or selling drugs on the job, creating another set of serious problems. Finally, the close friends and family members of drug and alcohol abusers (often referred to as “significant others”) are also affected in their ability to work by anxiety, depression and a variety of stress-related symptoms. These effects may even carry over into later generations in the form of residual work problems in adults whose parents suffered from alcoholism (Woodside 1992). Health expenditures for employees with serious alcohol problems are about twice as high as health costs for other employees (Institute for Health Policy 1993). Health costs for members of their families are also increased (Children of Alcoholics Foundation 1990).

Costs to Society

For the above reasons and others, drug and alcohol use and abuse have created a major economic burden on many societies. For the United States, the societal cost estimated for the year 1985 was US$70.3 billion (thousand millions) of for alcohol and $44 billion for other drugs. Of the total alcohol-related costs, $27.4 billion (about 39% of the total) was attributed to lost productivity. The corresponding figure for other drugs was $6 billion (about 14% of the total) (US Department of Health and Human Services 1990). The remainder of the cost accruing to society as a result of drug and alcohol abuse includes the costs for the treatment of medical problems (including AIDS and alcohol-related birth defects), vehicle crashes and other accidents, crime, property destruction, incarceration and the social welfare costs of family support. Although some of these costs may be attributed to the socially acceptable use of psychoactive substances, the vast majority are associated with drug and alcohol abuse and dependence.

Drug and Alcohol Use, Abuse and Dependence

A simple way to categorize the patterns of use of psychoactive substances is to distinguish among non-hazardous use (use in socially accepted patterns that neither create harm nor involve a high risk of harm), drug and alcohol abuse (use in high risk or harm-producing ways) and drug and alcohol dependence (use in a pattern characterized by signs and symptoms of the dependence syndrome).

Both the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, 4th edition (DSM-IV) specify diagnostic criteria for drug and alcohol-related disorders. The DSM-IV uses the term abuse to describe patterns of drug and alcohol use that cause impairment or distress, including interference with work, school, home or recreational activities. This definition of the term is also meant to imply recurrent use in physically hazardous situations, such as repeatedly driving while impaired by drugs or alcohol, even if no accident has yet occurred. The ICD-10 uses the term harmful use instead of abuse and defines it as any pattern of drug or alcohol use that has caused actual physical or psychological harm in an individual who does not meet the diagnostic criteria for drug or alcohol dependence. In some cases drug and alcohol abuse is an early or prodromal stage of dependence. In others, it constitutes an independent pattern of pathological behaviour.

Both the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV use the term psychoactive substance dependence to describe a group of disorders in which there is both interference with functioning (in job, family and social arenas) and an impairment in the individual’s ability to control the use of the drug. With some substances, a physiological dependence develops, with increased tolerance to the drug (higher and higher doses required to obtain the same effects) and a characteristic withdrawal syndrome when use of the drug is abruptly discontinued.

A definition recently prepared by the American Society of Addiction Medicine and the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence of the United States describes the features of alcoholism (a term usually employed as a synonym for alcohol dependence) as follows:

Alcoholism is a primary, chronic disease with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. The disease is often progressive and fatal. It is characterized by impaired control over drinking, preoccupation with the drug alcohol, use of alcohol despite adverse consequences, and distortions in thinking, most notably denial. Each of these symptoms may be continuous or periodic. (Morse and Flavin 1992)

The definition then goes on to explain the terms used, for example, that the qualification “primary” implies that alcoholism is a discrete disease rather than a symptom of some other disorder, and that “impaired control” means that the affected person cannot consistently limit the duration of a drinking episode, the amount consumed or the resulting behaviour. “Denial” is described as referring to a complex of physiological, psychological and culturally-influenced manoeuvres that decrease the recognition of alcohol-related problems by the affected individual. Thus, it is common for persons suffering from alcoholism to regard alcohol as a solution to their problems rather than as a cause.

Drugs capable of producing dependence are commonly divided into several categories, as listed in table 1. Each category has both a specific syndrome of acute intoxication and a characteristic combination of destructive effects related to long-term heavy use. Although individuals often suffer from dependency syndromes relating to a single substance (e.g., heroin), patterns of multiple drug abuse and dependence are also common.

Table 1. Substances capable of producing dependence.

|

Category of drug |

Examples of general effects |

Comments |

|

Alcohol (e.g., beer, wine, spirits) |

Impaired judgement, slowed reflexes, impaired motor function, somnolence, coma-overdose may be fatal |

Withdrawal may be severe; danger to foetus if used excessively in pregnancy |

|

Depressants (e.g., sleeping medicines, sedatives, some tranquillizers) |

Inattention, slowed reflexes, depression, impaired balance, drowsiness, coma-overdose may be fatal |

Withdrawal may be severe |

|

Opiates (e.g., morphine, heroin, codeine, some prescription pain medications) |

Loss of interest, “nodding”-overdose may be fatal. Subcutaneous or intravenous abuse may spread Hepatitis B, C and HIV/AIDS via needle-sharing |

|

|

Stimulants (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines) |

Elevated mood, overactivity, tension/anxiety, rapid heartbeat, constriction of blood vessels |

Chronic heavy use may lead to paranoid psychosis. Use by injection may spread Hepatitis B, C and HIV/AIDS via needle-sharing |

|

Cannabis (e.g., marijuana, hashish) |

Distorted time sense, impaired memory, impaired coordination |

|

|

Hallucinogens (e.g., LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), PCP (phencyclidine), mescaline) |

Inattention, sensory illusions, hallucinations, disorientation, psychosis |

Does not produce withdrawal symptoms but users may experience “flashbacks” |

|

Inhalants (e.g., hydrocarbons, solvents, gasoline) |

Intoxication similar to alcohol, dizziness, headache |

May cause long- term organ damage (brain, liver, kidney) |

|

Nicotine (e.g., cigarettes, chewing tobacco, snuff) |

Initial stimulant, later depressant effects |

May produce withdrawal symptoms. Implicated in causing a variety of cancers, cardiac and pulmonary diseases |

Drug and alcohol-related disorders often affect the employee’s family relationships, interpersonal functioning and health before obvious work impairments are noticed. Therefore, effective workplace programmes cannot be limited to efforts at achieving drug and alcohol abuse prevention on the job. These programmes must combine employee health education and prevention with adequate provisions for intervention, diagnosis and rehabilitation as well as long-term follow-up of affected employees after their reintegration into the workforce.

Approaches to Drug and Alcohol-relatedProblems in the Workplace

Concern over the serious productivity losses caused by drug and alcohol abuse and dependence have led to several related approaches on the part of governments, labour and industries. These approaches include so-called “drug-free workplace policies” (including chemical testing for drugs) and employee assistance programmes.

One example is the approach taken by the United States Military Services. In the early 1980s successful anti-drug policies and drug testing programmes were established in each branch of the US military. As a result of its programme, the US Navy reported a dramatic fall in the proportion of random urine tests of its personnel that were positive for illicit drugs. The positive test rates for those under age 25 fell from 47% in 1982, to 22% in 1984, to 4% in 1986 (DeCresce et al. 1989). In 1986 the President of the United States issued an executive order requiring that all federal government employees refrain from illegal drug use, whether on or off the job. As the largest single employer in the United States, with over two million civilian employees, the federal government thereby assumed the lead in developing a national drug-free workplace movement.

In 1987, following a fatal railway accident linked to marijuana abuse, the US Department of Transportation ordered a drug and alcohol testing programme for all transportation workers, including those in private industry. Managements in other work settings have followed suit, establishing a combination of supervision, testing, rehabilitation and follow-up in the workplace that has shown consistently successful results.

The case-finding, referral and follow-up component of this combination, the employee assistance programme (EAP), has become an increasingly common feature of employee health programmes. Historically, EAPs evolved from more narrowly-focused employee alcoholism programmes that had been pioneered in the United States during the 1920s and expanded more rapidly in the 1940s during and after the Second World War. Current EAPs are customarily established on the basis of a clearly enunciated company policy, often developed by joint agreement between management and labour. This policy includes rules of acceptable workplace behaviour (e.g., no alcohol or illicit drugs) and a statement that alcoholism and other drug and alcohol dependence are considered treatable diseases. It also includes a statement of confidentiality, guaranteeing the privacy of sensitive personal employee information. The programme itself conducts preventive education for all employees and special training for supervisory personnel in identifying job performance problems. Supervisors are not expected to learn to diagnose drug and alcohol-related problems. Rather, they are trained to refer employees who show problematic job performance to the EAP, where an assessment is made and a plan of treatment and follow-up is formulated, as appropriate. Treatment is usually provided by community resources outside the workplace. EAP records are kept confidentially as a matter of company policy, with reports relating only to the subject’s degree of cooperation and general progress released to management except in cases of imminent danger.

Disciplinary action is usually suspended as long as the employee cooperates with treatment. Self-referrals to the EAP are also encouraged. EAPs that help employees with a wide range of social, mental health and drug and alcohol-related problems are known as “broad-brush” programmes to distinguish them from programmes that focus only on drug and alcohol abuse.

There is no question of the appropriateness of employers’ prohibiting the use of alcohol and other drugs during working hours or in the workplace. However, the right of the employer to prohibit the use of such substances away from the workplace during off hours has been disputed. Some employers have said, “I don’t care what employees do off the job as long as they report on time and are able to perform adequately,” and some labour representatives have opposed such a prohibition as an intrusion on the worker’s privacy. Yet, as noted above, excess use of drugs or alcohol during off-hours can affect work performance. This is recognized by airlines when they prohibit all use of alcohol by air crews during a specified number of hours prior to flight time. Although the prohibitions of alcohol use by an employee before flying or driving a vehicle are generally accepted, blanket prohibitions of tobacco, alcohol or other drug use outside of the workplace have been more controversial.

Workplace drug testing programmes

Along with EAPs, increasing numbers of employers have also instituted workplace drug testing programmes. Some of these programmes test only for illicit drugs, while others include breath or urine testing for alcohol. Testing programmes may involve any of the following components:

- pre-employment testing

- random testing of employees in sensitive positions (e.g., nuclear reactor operators, pilots, drivers, operators of heavy machinery)

- testing “for cause” (e.g., after an accident or if a supervisor has good reason to suspect that the employee is intoxicated)

- testing as part of the follow-up plan for an employee returning to work after treatment for drug or alcohol abuse or dependence.

Drug testing programmes create special responsibilities for those employers who undertake them (New York Academy of Medicine 1989). This is discussed more fully under “Ethical Issues” in the Encyclopaedia. If employers rely on urine tests in making employment and disciplinary decisions in drug-related cases, the legal rights of both employers and employees must be protected by meticulous attention to collection and analysis procedures and to the interpretation of laboratory results. Specimens must be collected carefully and labelled immediately. Because drug users may attempt to evade detection by substituting a sample of drug-free urine for their own or by diluting their urine with water, the employer may require that the specimen be collected under direct observation. Because this procedure adds time and expense to the procedure it may be required only in special circumstances rather than for all tests. Once the specimen is collected, a chain-of-custody procedure is followed, documenting each movement of the specimen to protect it from loss or misidentification. Laboratory standards must ensure specimen integrity, with an effective programme of quality control in place, and staff qualifications and training must be adequate. The test used must employ a cut-off level for the determination of a positive result that minimizes the possibility of a false positive. Finally, positive results found by screening methods (e.g., thin-layer chromatography or immunological techniques) should be confirmed to eliminate false results, preferably by the techniques of gas chromatography or mass spectrometry, or both (DeCresce et al. 1989). Once a positive test is reported, a trained occupational physician (known in the United States as a medical review officer) is responsible for its interpretation, for example, ruling out prescribed medication as a possible reason for the test results. Performed and interpreted properly, urine testing is accurate and may be useful. However, industries must calculate the benefit of such testing in relationship to its cost. Considerations include the prevalence of drug and alcohol abuse and dependence in the prospective workforce, which will influence the value of pre-employment testing, and the proportion of the industry’s accidents, productivity losses and medical benefit costs related to the abuse of psychoactive substances.

Other methods of detecting drug and alcohol-related problems

Although urine testing is an established screening method for detecting drugs of abuse, there are other methods available to EAPs, occupational physicians and other health professionals. Blood alcohol levels may be estimated by means of breath testing. However, a negative chemical test of any kind does not rule out a drug or alcohol problem. Alcohol and some other drugs are metabolized rapidly and their aftereffects may continue to impair work performance even when the drugs are no longer detectable on a test. On the other hand, the metabolites produced by the human body after the ingestion of certain drugs may remain in the blood and urine for many hours after the drug’s effects and aftereffects have subsided. A positive urine test for drug metabolites therefore does not necessarily prove that the employee’s work is drug-impaired.

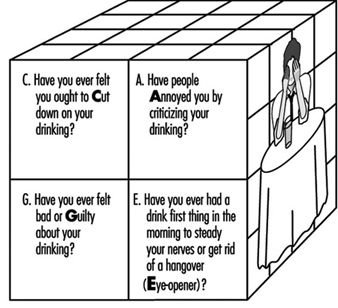

In making an assessment of employee drug and alcohol-related problems a variety of clinical screening instruments are used (Tramm and Warshaw 1989). These include pencil-and-paper tests, such as the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) (Selzer 1971), the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) developed for international use by the World Health Organization (Saunders et al. 1993), and the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) (Skinner 1982). In addition, there are simple sets of questions that can be incorporated into history-taking, for example the four CAGE questions (Ewing 1984) illustrated in figure 2. All of these methods are used by EAPs to evaluate employees referred to them. Employees referred for job performance problems such as absences, lateness and decreased productivity on the job should additionally be evaluated for other mental health problems such as depression or compulsive gambling, which may also produce impairments in job performance and are often associated with drug and alcohol-related disorders (Lesieur, Blume and Zoppa 1986). With respect to pathological gambling, a paper-and-pencil screening test, the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) is available (Lesieur and Blume 1987).

Figure 2. The CAGE questions.

Treatment of Disorders Related to theUse of Drugs and Alcohol

Although each employee presents a unique combination of problems to the addiction treatment professional, the treatment of disorders related to drug and alcohol use usually consists of four overlapping phases: (1) identification of the problem and (as necessary) intervention, (2) detoxification and general health assessment, (3) rehabilitation, and (4) long-term follow-up.

Identification and intervention

The first phase of treatment involves confirming the presence of a problem caused by the use of drugs or alcohol (or both) and motivating the affected individual to enter treatment. The employee health programme or company EAP has the advantage of using the employee’s concern both for health and job security as motivational factors. Workplace programmes are also likely to understand the employee’s environment and his or her strengths and weaknesses, and can thus choose the most appropriate treatment facility for referral. An important consideration in making a referral for treatment is the nature and extent of workplace-based health insurance coverage for the treatment of drug and alcohol-induced disorders. Policies with coverage of the full range of inpatient and outpatient treatments offer the most flexible and effective options. In addition, the involvement of the employee’s family at the intervention stage is often helpful.

Detoxification and general health assessment

The second stage combines the appropriate treatment needed to help the employee attain a drug and alcohol-free state with a thorough evaluation of the patient’s physical, psychological, family, interpersonal and work-related problems. Detoxification involves a short period—several days to several weeks—of observation and treatment for the elimination of the drug of abuse, recovery from its acute effects, and control of any symptoms of withdrawal. While detoxification and the assessment activities are progressing, the patient and “significant others” are educated about the nature of drug and alcohol dependence and recovery. They and the patient are also introduced to the principles of self-help groups, where this modality is available, and the patient is motivated to continue in treatment. Detoxification may be carried out in an inpatient or outpatient setting, depending on the needs of the individual. Treatment techniques found useful include a variety of medications, augmented by counselling, relaxation training and other behavioural techniques. Pharmacological agents used in detoxification include drugs which can substitute for the drug of abuse to relieve withdrawal symptoms and then be gradually reduced in dosage until the patient is drug-free. Phenobarbital and the longer-acting benzodiazepines are often used this way to achieve detoxification in the case of alcohol and sedative drugs. Other medicines are used to relieve withdrawal symptoms without substituting a similarly-acting drug of abuse. For example, clonidine is sometimes used in the treatment of opiate withdrawal symptoms. Acupuncture has also been used as an aid in detoxification, with some positive results (Margolin et al. 1993).

Rehabilitation