Contract Occupational Health Services in the United States

Setting

Employers in the United States have long provided medical care for injured workers through the use of private physicians, clinics, immediate-care facilities and hospital emergency departments. This care for the most part has been episodic and rarely coordinated, as only the largest corporations could provide in-house occupational health services.

A recent survey of 22,457 companies of fewer than 5,000 employees in a suburban area of Chicago found that 93% had less than 50 employees and only 1% employed more than 250 employees. Of this group, 52% utilized a specific provider for their work injuries, 24% did not utilize a specific provider and another 24% allowed the employee to seek his or her own provider. Only 1% of the companies utilized a medical director to provide care. These companies make up 99% of all employers in the surveyed area, representing over 524,000 employees (National Health Systems 1992).

Since the passage of the act which created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in 1970, and with the accompanying changes in health care financing that have taken place since that time, the focus and priorities of care have changed. Insurance costs for workers’ compensation and group health care have risen from 14 to 26% annually from 1988 to 1991 (BNA 1991). In 1990, health care costs accounted for the single largest portion of the $53 billion spent in the United States for workers’ compensation benefits, and in 1995, medical benefits are expected to reach 50% of a total $100 billion price tag for workers’ compensation costs (Resnick 1992).

Premium costs vary by state because of differing workers’ compensation regulations. The Kiplinger Washington Letter of 9 September 1994 states, “In Montana, contractors pay an average of $35.29 in compensation insurance for every $100 of payroll. In Florida, it’s $21.99. Illinois, $19.48. Same coverage costs $5.55 in Indiana or $9.55 in South Carolina.” As the need for economical workers’ compensation care has evolved, employers are demanding more assistance from their health care providers.

The bulk of this medical care is rendered by independently owned medical facilities. Employers may contract for this care, develop a relationship with a provider or secure it on an as-needed basis. Most care is rendered on a fee-for-service basis, with the beginnings of capitation and direct contracting emerging during the later half of the 1990s.

Types of Services

Employers universally require that occupational health services include acute treatment of injuries and illnesses such as sprains, strains, back and eye injuries and lacerations. These make up the majority of acute cases seen in an occupational health programme.

Often, examinations are requested that are given pre-placement or after a job offer, to determine prospective employees’ ability to safely perform the work required without injury to themselves or others. These examinations must be evaluated consistently with US law as embodied in the Americans with Disabilities Act. This law forbids discrimination in hiring based on a disability that does not prevent an individual from performing the essential functions of the prospective job. The employer is further expected to make a “reasonable accommodation” to a disabled employee (EEOC and Department of Justice 1991).

Though required by law only for certain job categories, substance abuse testing for drugs and/or alcohol is now performed by 98% of the Fortune 200 companies in the United States. These tests may include measurements of urine, blood and breath for levels of illicit drugs or alcohol (BNA 1994).

In addition, an employer may require specialized services such as OSHA-mandated medical surveillance tests—for instance, respirator fitness examinations, based on a worker’s physical capacity and pulmonary function, assessing the worker’s ability to wear a respirator with safety; asbestos examinations and other chemical exposure tests, tailored to assess an individual’s health status with respect to possible exposure and long-term effects of a given agent on the person’s overall health.

In order to assess the health status of key employees, some companies contract for physical examinations for their executives. These examinations are generally preventive in nature and offer extensive health assessment, including laboratory testing, x rays, cardiac stress testing, cancer screening and lifestyle counselling. The frequency of these examinations is often based on age rather than type of work.

Periodic fitness examinations are often contracted for by municipalities to assess the health status of fire and police officers, who are generally tested to measure their physical ability to handle physically stressful situations and to determine whether exposures have occurred in the workplace.

An employer may also contract for rehabilitative services, including physical therapy, work hardening, workplace ergonomic assessments as well as vocational and occupational therapies.

More recently, as a benefit to employees and in an effort to decrease health care costs, employers are contracting for wellness programmes. These prevention-oriented screenings and educational programmes seek to assess health so that appropriate interventions might be offered to alter lifestyles that contribute to disease. Programmes include cholesterol screening, health risk appraisals, smoking cessation, stress management and nutrition education.

Programmes are being developed in all areas of health care to meet the needs of employees. The employee assistance program (EAP) is another recent programme developed to provide counselling and referral services to employees with substance abuse, emotional, family and/or financial problems which employers have determined have an effect on the employee’s ability to be productive.

A service that is relatively new to occupational health is case management. This service, usually provided by nurses or clerical personnel supervised by nurses, has effectively reduced costs while ensuring appropriate quality care for the injured worker. Insurance companies have long provided management of claims costs (the dollars spent on workers’ compensation cases) at a point when the injured worker has been off work for a specified length of time or when a certain dollar amount has been reached. Case management is a more proactive and concurrent process which may be applied from the first day of the injury. Case managers direct the patient to the appropriate level of care, interact with the treating physician to determine what types of modified work the patient is medically capable of performing, and work with the employer to ensure that the patient is performing work which will not worsen the injury. The case manager’s focus is to return the employee to a minimum of modified duty as quickly as possible as well as to identify good quality physicians whose results will best benefit the patient.

The Providers

Services are available through a variety of providers with varying degrees of expertise. The private physician’s office may offer pre-placement examinations and substance abuse testing as well as follow-up of acute injuries. The physician’s office generally requires appointments and has limited hours of service. If the capabilities exist, the private physician may also offer executive examinations or may refer the patient to a nearby hospital for extensive laboratory, x-ray and stress testing.

The industrial clinic generally offers acute care of injuries (including follow-up care), pre-placement examinations and substance abuse testing. They often have x-ray and laboratory capabilities and may have physicians who have experience in assessing the workplace. Again, their hours are generally limited to business hours so that employers with second- and third-shift operations may need to utilize an emergency department during evenings and weekends. The industrial clinic rarely treats the private patient, and it is generally perceived as the “company doctor”, since arrangements are usually made to bill the employer or the company’s insurance carrier directly.

Immediate care facilities are another alternative delivery site. These facilities are walk-in providers of general medical care and require no appointments. These facilities generally are equipped with x-ray and laboratory capabilities and physicians experienced in emergency medicine, internal medicine or family practice. The type of client ranges from the paediatrics patient to the adult with a sore throat. In addition to acute injury care and minor follow-up of injured employees, these facilities may perform pre-placement physicals and substance abuse testing. Those facilities which have developed an occupational health component often provide periodic exams and OSHA-mandated screenings, and may have contractual relationships with additional providers for services that they do not themselves offer.

The hospital emergency room is often the site of choice for treatment of acute injuries and has generally been capable of little else in terms of occupational health services. This has been the case although the hospital has had the resources to provide most of the required services with the exception of those offered by physicians with expertise in occupational medicine. Yet an emergency department alone lacks the managed care and return-to-work expertise now being demanded by industry.

Hospital-Based Programmes

Hospital administrations have become cognizant that they not only have the resources and technology available but that workers’ compensation was one of the last “insurance” programmes which would pay fees for service, thereby boosting revenues hurt by discounting arrangements that were made with managed care insurance companies such as HMOs and PPOs. These managed care companies, as well as the federally and state funded Medicare and Medicaid programmes for general health care, have demanded shorter lengths of stay and have imposed a payment system based on “diagnosis-related grouping” (DRG). These schemes have forced hospitals to lower costs by seeking improved coordination of care and new revenue-producing products. Fears arose that costs would be shifted from group health managed care to workers’ compensation; in many cases these fears were well-founded, with costs for treating an injured back under workers’ compensation two to three times the cost under group health plans. A 1990 Minnesota Department of Labour and Industry study reported that costs of treatment for sprains and strains were 1.95 times greater, and those for back injuries 2.3 times greater, under workers’ compensation than under group health insurance plans (Zaldman 1990).

Several different hospital delivery models have evolved. These include the hospital-owned clinic (either on campus or off), the emergency department, the “fast-track” (non-acute emergency department), and administratively managed occupational health services. The American Hospital Association reported that Ryan Associates and Occupational Health Research had studied 119 occupational health programmes in the United States (Newkirk 1993). They found that:

- 25.2% were hospital emergency department based

- 24.4% were hospital non-emergency department based

- 28.6% were hospital free-standing clinics

- 10.9% were independently owned free-standing clinics

- 10.9% were other types of programmes.

All of these programmes assessed costs on a fee-for-service basis and offered a variety of services which, in addition to treatment of acutely injured workers, included pre-placement examinations, drug and alcohol testing, rehabilitation, workplace consulting, OSHA-mandated medical surveillance, executive physicals and wellness programmes. In addition, some offered employee assistance programmes, onsite nursing, CPR, first aid and case management.

More often today hospital occupational health programmes are adding a nursing model of case management. Within such a model incorporating integrated medical management, total workers’ compensation costs can be lowered 50%, which is a significant incentive for the employer to utilize providers that afford this service (Tweed 1994). These cost reductions are generated by a strong focus on the need for early return to work and for consultation on modified work programmes. The nurses work with the specialists to help define medically acceptable work that an injured employee can perform safely and with restrictions.

In most states, US workers receive two-thirds of their salary while receiving temporary workers’ compensation for total disability. When they return to modified work, they continue to provide a service for their employers and maintain their self-esteem through work. Workers who have been off work six or more weeks frequently never return to their full employment and are often forced to perform lower-paying and less skilled jobs.

The ultimate goal of a hospital-based occupational health programme is to allow patients access to the hospital for work injury treatment and to continue with the hospital as their primary provider of all health care services. As the United States moves to a capitated health care system, the number of covered lives a hospital serves becomes the prime indicator of success.

Under this capitated form of health care financing, employers pay a per capita rate to providers for all health care services that their employees and their dependants may need. If the individuals covered under such a plan stay healthy, then the provider is able to profit. If the covered lives are high utilizers of services, the provider may not earn enough revenue from premiums to cover the costs of care and may therefore lose money. Several states in the United States are moving toward capitation for group health insurance and a few are piloting 24-hour coverage for all health care, including workers’ compensation medical benefits. Hospitals will no longer judge success on patient census but on a ratio of covered lives to costs.

Comprehensive hospital-based occupational health programmes are designed to fill a need for a high-quality comprehensive occupational medicine programme for the industrial and corporate community. The design is based on the premise that injury care and pre-placement physicals are important but alone do not constitute an occupational medicine programme. A hospital serving many companies can afford an occupational medicine physician to oversee medical services, and therefore, a broader occupational focus can be gained, allowing for toxicology consultations, worksite evaluations and OSHA-mandated examin-ations for such contaminants as asbestos or lead and for equipment such as respirators, in addition to the usual services of work injury treatment, physical examinations and drug screening. Hospitals also have the resources necessary to provide a compute-rized database and case management system.

By providing employers with a single full service centre for their employees’ health care needs, the occupational health programme can better ensure that the employee receives quality, compassionate health care in the most appropriate setting, at the same time reducing costs to the employer. Occupational health providers can monitor trends within a company or an industry and make recommendations to reduce workplace accidents and improve safety.

A comprehensive hospital-based occupational health programme allows the small employer to share the services of a corporate medical department. Such a programme provides prevention and wellness as well as acute care service and permits a sharper focus on promotion of health for US workers and their families.

Corporate Occupational Health Services in the United States: Services Provided Internally

Industrial medical programmes vary in both content and structure. It is a common conception that industrial medical programmes are supported only by large corporations and are comprehensive enough to evaluate all workers for all possible adverse effects. However, the programmes implemented by industries vary considerably in their scope. Some programmes offer only pre-placement screening, while others offer total medical surveillance, health promotion and other special services. In addition, the structures of programmes differ from one another, as do the members of the safety and health teams. Some programmes contract with an off-site physician to perform medical services, while others have a health unit at the site staffed by physicians and nursing personnel and backed by a staff of industrial hygienists, engineers, toxicologists and epidemiologists. The duties and responsibility of these members of the safety and health team will vary according to the industry and the risk involved.

Motivation for Industrial Medical Programmes

The medical monitoring of workers is motivated by multiple factors. First, there is the concern for the general safety and health of the employee. Second, a monetary benefit results from a surveillance effort through increased productivity of the employee and reduced medical care costs. Third, compliance with the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA), with equal employment opportunity requirements (EEO), the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and other statutory guidelines is mandatory. Finally, there is the spectre of civil and criminal litigation if adequate programmes are not established or are found to be inadequate (McCunney 1995; Bunn 1985).

Types of Occupational Health Servicesand Programmes

Occupational health services are determined through a needs assessment. Factors that affect which type of occupational health service is to be utilized include the potential risks of normal operations, the demographics of the workforce and management’s interest in occupational health. Health services are dependent on the type of industry, the physical, chemical or biological hazards present, and the methods used to prevent exposure, as well as government and industry standards, regulations and rulings.

Important general health services tasks include the following:

- evaluation of employees’ ability to perform their assigned duties in a safe manner (via pre-placement evaluations)

- recognition of early symptoms and signs of work-related health effects and appropriate intervention (medical surveillance examinations can reveal these)

- provision of treatment and rehabilitation for occupational injuries and illnesses and non-occupational disorders that affect work performance (work-related injuries)

- promotion and maintenance of employees’ health (wellness)

- evaluation of a person’s ability to work in light of a chronic medical disorder (an independent medical examination is required in such a case)

- supervision of policies and programmes related to worksite health and safety.

Location of Health Services Facilities

Onsite facilities

Delivery of occupational health services today is increasingly provided through contractors and local medical facilities. However, onsite services formed by employers were the traditional approach taken by industry. In settings with a substantial number of employees or certain health risks, onsite services are cost-effective and provide high-quality services. The extent of these programmes varies considerably, ranging from part-time nursing support to a fully-staffed medical facility with full-time physicians.

The need for onsite medical service is usually determined by the nature of the company’s business and the potential health hazards present in the workplace. For example, a company that uses benzene as a raw material or ingredient in its manufacturing process will probably need a medical surveillance programme. In addition, many other chemicals handled or produced by the same plant may be toxic. In these circumstances, it may be economically feasible as well as medically advisable to provide onsite medical services. Some onsite services provide occupa-tional nursing support during daytime working hours and may also cover second and third shifts or weekends.

Onsite services should be performed in plant areas compatible with the practice of medicine. The medical facility should be centrally located to be accessible to all employees. Heating and cooling needs should be considered to permit the most economical use of the facility. A rule of thumb that has been used in allocating floor space to an in-house medical unit is one square foot per employee for units servicing up to 1,000 employees; this figure should probably include a minimum of 300 square feet. The cost of space and several relevant design considerations have been described by specialists (McCunney 1995; Felton 1976).

For some manufacturing facilities located in rural or otherwise remote areas, services may usefully be provided in a mobile van. If such an installation is made available, the following recommendations may be made:

- Assistance should be furnished to companies whose in-house medical services are not fully equipped to cope with medical surveillance programmes that require the use of special equipment, such as audiometers, spirometers or x-ray machines.

- Medical surveillance programmes should be made available in remote geographical areas, especially to ensure uniformity in data collected for epidemiology studies. For example, to enhance the scientific accuracy of a study of occupational lung disorders, a similar spirometer should be used and the preparation of chest films should be performed according to appropriate international standards, such as those of the International Labour Organization (ILO).

- Data from different sites should be coordinated for entry into a computer software programme.

A company that relies on a mobile van service, however, will still require a physician to conduct pre-placement examinations and to assure the quality of the services provided by the mobile van company.

Services Most Commonly Performedin the In-house Facility

An onsite assessment is essential to determine the type of health services appropriate for a facility. The most common services provided in the occupational health setting are pre-placement evaluations, assessment of work-related injury or illness and medical surveillance examinations.

Pre-placement evaluations

The pre-placement examination is performed after a person has been given a conditional offer of a job. The ADA uses pre-employment to mean that the person is to be hired if he or she passes the physical examination.

The pre-placement examination should be performed with attention to the job duties, including physical and cognitive requirements (for safety sensitivity) and potential exposure to hazardous materials. The content of the examination depends on the job and the worksite assessment. For example, jobs that require use of personal protective equipment, such as a respirator, often include a pulmonary function study (breathing test) as part of the pre-placement examination. Those involved in the US Department of Transportation (DOT) activities usually require urinary drug testing. To avoid errors in either the content or the context of the examination, it is advisable to develop standard protocols to which the company and the examining physician agree.

After the examination, the physician provides a written opinion about the person’s suitability for performing the job without health or safety risk to self or others. Under usual circumstances, medical information is not to be divulged on this form, merely fitness for duty. This form of communication can be a standard form that should then be placed in the employee’s file. Specific medical records, however, remain at the health facility and are maintained only by a physician or nurse.

Work-related injuries and illnesses

Prompt, quality medical care is essential for the employee sustaining a work-related injury or occupational illness. The medical unit or contract physician should treat employees who are injured at work or who experience work-related symptoms. The company’s medical service has an important role to play in the management of workers’ compensation costs, especially in performing return-to-work assessments following absence due to an illness or injury. A major function of the medical professional is the coordination of rehabilitation services of such absentees to insure a smooth return to work. The most effective rehabilitation programmes make use of modified-duty or alternative assignments.

An important task of the company’s medical adviser is to determine the relationship between exposure to hazardous agents and illness, injury or impairment. In some states, the employee may choose his or her attending physician, whereas in other states the employer may direct or at least suggest evaluation by a specific physician or health care facility. The employer usually has the right to specify a physician to conduct a “second opinion” examination, especially in the context of a protracted recovery or serious medical disorder.

The nurse or physician advises management on the recordability of occupational injuries and illnesses in accordance with OSHA record-keeping requirements, and needs to be familiar with both OSHA and Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) guidelines. Management must assure that the health care provider is thoroughly familiar with these guidelines.

Medical surveillance examinations

Medical surveillance examinations are required by some OSHA standards for exposure to some substances (asbestos, lead and so on) and are recommended as being in accordance with good medical practice for exposure to others, such as solvents, metals and dusts such as silica. Employers must make these examinations, when required by OSHA standards, available at no cost to employees. Although the employee may decline to participate in an examination, the employer may specify that the examination is a condition of employment.

The purpose of medical surveillance is to prevent work-related illnesses through early recognition of problems, such as abnormal laboratory results that may be associated with the early stages of a disease. The employee is then re-evaluated at subsequent intervals. Consistency in the medical follow-up of abnormalities uncovered during medical surveillance examinations is essential. Although management should be apprised of any medical disorders related to work, medical conditions not arising from the workplace should remain confidential and be treated by the family physician. In all cases, employees should be informed of their results (McCunney 1995; Bunn 1985, 1995; Felton 1976).

Management Consultation

Although the occupational health physician and nurse are most readily recognized through their hands-on medical skills, they can also offer significant medical advice to any business. The health professional can develop procedures and practices for medical programmes including health promotion, substance abuse detection and training, and medical record-keeping.

For facilities with an in-house medical programme, a policy for the management of medical waste handling and related activities is necessary in accordance with the OSHA blood-borne pathogen standard. Training with respect to certain OSHA standards, such as the Hazard Communication Standard, the OSHA Standard on Access to Exposure and Medical Records, and OSHA record-keeping requirements, is an essential ingredient to a well-managed programme.

Emergency response procedures should be developed for any facility that is at increased risk of natural disaster or that handles, uses or manufactures potentially hazardous materials, in accordance with the Superfund Act Reauthorization Amendment (SARA). Principles of medical emergency response and disaster management should, with the assistance of the company’s physician, be incorporated in any site emergency response plan. Since the emergency procedures will differ depending on the hazard, the physician and nurse should be prepared to handle both physical hazards, such as those that occur in a radiation accident, and chemical hazards.

Health Promotion

Health promotion and wellness programmes to educate people on the adverse health effects of certain lifestyles (such as cigarette smoking, poor diet and lack of exercise) are becoming more common in industry. Although not essential to an occupational health programme, these services can be valuable to employees.

The incorporation of wellness and health promotion plans in the medical programme is recommended whenever feasible. The objectives of such a programme are a health-conscious, productive workforce. Health care costs can be reduced as a result of health promotion initiatives.

Substance Abuse Detection Programmes

Within the past few years, especially since the US Department of Transportation (DOT) Ruling on Drug Testing (1988), many organizations have developed drug testing programmes. In the chemical and other manufacturing industries, the most common type of urinary drug test is performed at the pre-placement evaluation. The DOT rulings on drug testing for interstate trucking, gas transmission operations (pipelines), and the railroad, coast guard and aviation industries are considerably broader and include periodic testing “for cause,” that is, for reasons of suspected substance abuse. Physicians are involved in drug screening programmes by reviewing results to assure that reasons other than illicit drug use are eliminated for individuals with positive tests. They must ensure the integrity of the testing process and confirm any positive test with the employee before releasing the results to management. An employee assistance programme and uniform company policy are essential.

Medical Records

Medical records are confidential documents which should be maintained by an occupational physician or nurse and stored in such a manner so as to protect their confidentiality. Some records, such as a letter indicating a person’s fitness for respirator use, should be kept onsite in the event of a regulatory audit. Specific medical test results, however, should be excluded from such files. Access to such records should be limited to the health professional, the employee and other persons designated by the employee. In some instances, such as the filing of a workers’ compensation claim, confidentiality is waived. The OSHA Access to Employee Exposure and Medical Records standard (29 CFR 1910.120) requires that employees be informed annually of their right of access to their medical records and of the location of such records.

Confidentiality of medical records must be preserved in accordance with legal, ethical and regulatory guidelines. Employees should be informed when medical information will be released to management. Ideally, an employee will be asked to sign a medical form that authorizes release of certain medical information, including laboratory tests or diagnostic material.

The first item in the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine Code of Ethics requires that “Physicians should accord the highest priority to the health and safety of individuals in both the workplace and the environment.” In the practice of occupational medicine, both employer and employee benefit if physicians are impartial and objective and apply sound medical, scientific and humanitarian principles.

International Programmes

In international occupational and environmental medicine, physicians working for US industries will have not only the traditional responsibilities of occupational and environmental physicians but will also have significant clinical management responsibilities. The responsibility of the medical department will include the clinical care of the employees and commonly the spouses and children of the employees. Servants, extended family and the community are often included in the clinical responsibilities. In addition, the occupational physician will also have responsibilities for occupational programmes related to workplace exposures and risks. Medical surveillance programmes, as well as pre-employment and periodic examinations are critical programme components.

Designing appropriate health promotion and prevention programmes is also a major responsibility. In the international arena, these prevention programmes will include issues in addition to those lifestyle issues commonly considered in the United States or Western Europe. Infectious diseases require a systematic approach to needed vaccination and chemoprophylaxis. Educational programmes for prevention must include attention to food-, water- and blood-borne pathogens and to general sanitation. Accident prevention program-mes must be considered in view of the high risk for traffic-related deaths in many developing countries. Special issues such as evacuation and emergency care must be given detailed scrutiny and appropriate programmes implemented. Environmental exposure to chemical, biological and physical hazards is often increased in developing countries. Environmental prevention programmes are based on multi-staged education plans with indicated biological testing. The clinical programmes to be developed internationally may include inpatient, outpatient, emergency and intensive care management of expatriates and national employees.

An ancillary programme for international occupational physicians is travel medicine. The safety of short-term rotational travellers or foreign residents requires special knowledge of the indicated vaccinations and other preventive measures on a global basis. In addition to recommended vaccinations, a knowledge of medical requirements for visas is imperative. Many countries require serologic testing or chest x rays, and some countries may take into account any significant medical condition in the decision to issue a visa for employment or as a residency requirement.

Employee assistance and marine and aviation programmes are also commonly included within the international occupational physician’s responsibilities. Emergency planning and the provision of appropriate medications and training in their use are challenging issues for sea and air vessels. Psychological support both of expatriate and national employees is often desirable and/or necessary. Employee assistance programmes may be extended to expatriates and special support given to family members. Drug and alcohol programmes should be considered within the social context of the given country (Bunn 1995).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the scope and organization of corporate occupational health programmes may vary widely. However, if appropriately discussed and implemented, these programmes are cost-effective, protect the company from legal liabilities and promote the occupational and general health of the workforce.

Governmental Occupational Health Agencies in the United States

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration(OSHA)

Purpose and organization

OSHA was created to encourage employers and workers to reduce workplace hazards and to implement effective safety and health programmes. This is accomplished by setting and enforcing standards, monitoring the performance of state OSHA programmes, requiring employers to maintain records of work-related injuries and illnesses, providing safety and health training for employers and employees and investigating complaints of workers who claim they have been discriminated against for reporting safety or health hazards.

OSHA is directed by an Assistant Secretary of Labor for Occupational Safety and Health, who reports to the Secretary of Labor. The OSHA headquarters is in Washington, DC, with ten regional offices and about 85 area offices. About half of the states administer their own state safety and health programmes, with federal OSHA responsible for enforcement in states without approved state programmes. The Occupational Safety and Health Act also requires that each federal government agency maintain a safety and health programme consistent with OSHA standards.

Programme and services

Standards form the basis of OSHA’s enforcement programme, setting out the requirements employers must meet to be in compliance. Proposed standards are published in the Federal Register with opportunities for public comment and hearings. Final standards are also published in the Federal Register and may be challenged in a US Court of Appeals.

In areas where OSHA has not established a standard, employers are required to follow the Occupational Safety and Health Act’s general duty clause, which states that each employer shall furnish “a place of employment which is free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees”.

OSHA has the right to enter the workplace to determine whether an employer is in compliance with requirements of the Act. OSHA places highest priority on investigating imminent danger situations, catastrophes and fatal accidents, employee complaints and scheduled inspections in highly hazardous industries.

If the employer refuses entry, the inspector can be required to obtain a search warrant from a US district judge or US magistrate. Both worker and employer representatives have a right to accompany OSHA inspectors on their plant visits. The inspector issues citations and proposed penalties for any violations found during the inspection and sets a deadline for correcting them.

The employer may contest the citation to the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission, an independent body established to hear challenges to OSHA citations and proposed fines. The employer may also appeal an unfavourable Review Commission decision to a federal court.

Consultation assistance is available at no cost to employers who agree to correct any serious hazards identified by the consultant. Assistance can be given in developing safety and health programmes and training workers. This service, which is targeted toward smaller employers, is largely funded by OSHA and provided by state government agencies or universities.

OSHA has a voluntary protection programme (VPP), which exempts workplaces from scheduled inspections if they meet certain criteria and agree to develop their own comprehensive safety and health programmes. Such workplaces must have lower than average accident rates and written safety programmes, make injury and exposure records available to OSHA and notify workers about their rights.

Resources

In 1995, the OSHA budget was $312 million, with about 2,300 employees. These resources are intended to provide coverage for more than 90 million workers throughout the United States.

State OSHA Programmes

Purpose and organization

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 gave state governments the option of regulating workplace safety and health.

States conduct their own programmes for setting and enforcing safety and health standards by submitting a state plan to OSHA for approval. The state plan details how the state proposes to set and enforce standards that are “at least as effective” as OSHA’s and to assume jurisdiction over state, city and other (non-federal) public employees whom OSHA itself does not otherwise cover. In these states, the federal government gives up direct regulatory responsibilities, and instead provides partial funding to the state programmes, and monitors the state activities for conformance with the national standards.

Programme and services

Approximately half of the states have chosen to administer their own programmes. Two other states, New York and Connecticut, have elected to keep the federal jurisdiction in their states, but to add a state workplace safety and health system that provides protection for public employees.

State-run OSHA programmes allow states to tailor resources and target regulatory efforts to match special needs in their states. For example, logging is done differently in the eastern and western United States. North Carolina, which runs its own OSHA programme, was able to target its logging regulations, outreach, training and enforcement programmes to address the safety and health needs of loggers in that state.

Washington State, which has a large agricultural economic base, developed agriculture safety requirements that exceed the mandated national minimums and translated safety information into Spanish to meet the needs of Spanish-speaking farm workers.

In addition to developing programmes that meet their special needs, states are able to develop programmes and enact regulations for which there might not be sufficient support at the federal level. California, Utah, Vermont and Washington have restrictions on workplace exposure to environmental tobacco smoke; Washington State and Oregon require that each employer develop worksite-specific injury and illness prevention plans; Utah’s standard for oil and gas drilling and the manufacture of explosives exceeds federal OSHA standards.

State programmes are permitted to conduct consultation programmes that provide free assistance to employers in identifying and correcting workplace hazards. These consultations, which are made only at the request of the employer, are kept separate from enforcement programmes.

Resources

In 1993, state-administered programmes had a total of about 1,170 enforcement personnel, according to the Occupational Safety and Health State Plan Association. In addition, they had about 300 safety and health consultants and nearly 60 training and education coordinators. The majority of these programmes are in state labour departments.

Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA)

Purpose and organization

The Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) sets and enforces standards to reduce injuries, illnesses and deaths in mines and mineral processing operations regardless of size, number of employees or method of extraction. MSHA is required to inspect every underground mine at least four times a year and every surface mine at least twice a year.

In addition to enforcement programmes, the Mine Safety and Health Act requires that the agency establish regulations on safety and health training for miners, upgrade and strengthen mine safety and health laws and encourage the participation of miners and their representatives in safety activities. MSHA also works with the mine operators to solve safety and health problems through education and training programmes and the development of engineering controls to reduce injuries.

Like OSHA, MSHA is directed by an Assistant Secretary of Labor. The coal mine safety and health activities are administered through ten district offices in the coal mining regions. The metal and non-metal mine safety and health activities are administered through six district offices in the mining areas of the country.

A number of staff offices that assist in administering the agency’s responsibilities are located at the headquarters in Arlington, Virginia. These include the Office of Standards, Regulations and Variances; the Office of Assessments; the Technical Support directorate; and the Office of Program Policy. In addition, the Educational Policy and Development Office oversees the agency’s training programme at the National Mine Health and Safety Academy in Beckley, West Virginia, which is the world’s largest institution devoted entirely to mine safety and health training.

Programme and services

Mining deaths and injuries have declined significantly during the last hundred years. From 1880 to 1910, thousands of coal miners were killed, with 3,242 dying in 1907 alone. Large numbers of miners were also killed in other sorts of mines. The average number of mining deaths has declined over the years to less than 100 per year today.

MSHA enforces the mine act provisions requiring mine operators to have an approved safety and health training plan which provides for 40 hours of basic training for new underground miners, 24 hours of training for new surface miners, 8 hours of annual refresher training for all miners and safety-related task training for miners assigned to new jobs. The National Mine Health and Safety Academy offers a wide variety of safety and health courses. MSHA provides special training programmes for managers and workers at small mining operations. MSHA training materials, including videotapes, films, publications and technical materials are available at the Academy and at district offices.

Resources

In 1995, MSHA had a budget of about $200 million and about 2,500 employees. These resources were responsible for ensuring the health and safety of about 113,000 coal miners and 197,000 miners in metal and non-metal mines.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

Purpose and organization

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) is the federal agency responsible for conducting research on occupational injuries and illnesses and transmitting recommended standards to OSHA. NIOSH funds education programmes for occupational safety and health professionals through Educational Resource Centres (ERCs) and training projects at universities throughout the United States. Under the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, NIOSH also conducts research and health hazard evaluations, and recommends mine health standards to the Mine Safety and Health Administration.

The Director of NIOSH reports to the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention within the Department of Health and Human Services. The NIOSH headquarters is in Washington, DC, with administrative offices in Atlanta, Georgia, and laboratories in Cincinnati, Ohio, and Morgantown, West Virginia.

Programme and services

NIOSH research is conducted both in the field and in the laboratory. Surveillance programmes identify the occurrence of work-related injury and disease. These include targeted data collection directed toward specific conditions, such as high blood lead levels in adults or injuries among adolescent workers. NIOSH also links data collected by states and other federal agencies to make it increasingly practicable to obtain a national picture of the effects of occupational hazards.

Field research is conducted at workplaces throughout the United States. These studies make it possible to identify hazards, evaluate the extent of exposures and determine the effectiveness of preventive measures. The right of entry into the workplace is essential to the ability of the Institute to conduct this research. This field research results in articles in the scientific literature as well as recommendations for preventing hazards at specific worksites.

Working with state health departments, NIOSH investigates on-the-job fatalities from specific causes, including electrocutions, falls, machine-related incidents and confined space entry accidents. NIOSH has a special programme to assist small businesses by developing inexpensive and effective technologies to control hazardous exposures at the source.

NIOSH conducts laboratory research to study workplace hazards under controlled conditions. This research assists NIOSH in determining the causes and mechanisms of workplace illnesses and injuries, developing tools for measuring and monitoring exposures, and developing and evaluating control technology and personal protective equipment.

About 17% of the NIOSH budget is devoted to funding service activities. Many of these service activities are also research-based, such as the health hazard evaluation programme. NIOSH conducts hundreds of health hazard evaluations each year when requested by employers, workers or federal and state agencies. After evaluating the worksite, NIOSH provides workers and employers with recommendations to reduce exposures.

NIOSH also responds to requests for information through a toll-free telephone number. Through this number, callers can obtain occupational safety and health information, request a health hazard evaluation or obtain a NIOSH publication. The NIOSH Home Page on the World Wide Web is also a good source of information about NIOSH.

NIOSH maintains a number of databases, including NIOSHTIC, a bibliographic database of occupational safety and health literature, and the Registry of Toxic Effects of Chemical Substances (RTECS), which is a compendium of toxicological data extracted from the scientific literature which fulfils the NIOSH mandate to “list all known toxic substances and concentrations at which toxicity is known to occur”.

NIOSH also tests respirators and certifies that they meet established national standards. This assists employers and workers in choosing the most appropriate respirator for specific hazardous environments.

NIOSH funds programmes at universities throughout the United States to train occupational medicine physicians, occupational health nurses, industrial hygienists and safety professionals. NIOSH also funds programmes to introduce safety and health into business, engineering and vocational schools. These programmes, which are either multidisciplinary ERCs or single-discipline project training grants, have made a significant contribution to the development of occupational health as a discipline and to meeting the need for qualified safety and health professionals.

Resources

NIOSH had about 900 employees and a budget of $133 million in 1995. NIOSH is the only federal agency with statutory responsibility to conduct occupational safety and health research and professional training.

The Future of Occupational Safetyand Health Programmes

The future of these federal occupational safety and health programmes in the United States is very much in doubt in the anti-regulatory climate of the 1990s. There continue to be serious proposals from Congress that would drastically change how these programmes operate.

One proposal would require the regulatory agencies to focus more on education and consultation and less on standards setting and enforcement. Another would set up requirements for complex cost benefit analyses that must be conducted before standards could be established. NIOSH has been threatened with abolition or merger with OSHA. And all these agencies have been targeted for budget reductions.

If enacted, these proposals would greatly decrease the federal role in conducting research and in setting and enforcing uniform occupational safety and health standards throughout the United States.

Occupational Health Services in the United States: Introduction

History

Occupational health services in the United States have always been divided in function and control. The extent to which government at any level should make rules affecting working conditions has been a matter of continuing controversy. Furthermore, there has been an uneasy tension between the state and federal governments about which should take primary responsibility for preventive services based primarily upon laws governing workplace safety and health. Monetary compensation for workplace injury and illness has primarily been the responsibility of private insurance companies, and safety and health education, with only recent changes, has been left largely to unions and corporations.

It was at the state level that the first governmental effort to regulate working conditions took place. Occupational safety and health laws began to be enacted by states in the 1800s when increasing levels of industrial production began to be accompanied by high accident rates. Pennsylvania enacted the first coal mine inspection act in 1869, and Massachusetts was the first state to pass a factory inspection law in 1877.

By 1900 the more industrialized states had some laws in place regulating some workplace hazards. Early in the twentieth century, New York and Wisconsin led the nation in developing more comprehensive occupational safety and health programmes.

Most states adopted worker’s compensation laws mandating private no-fault insurance between 1910 and 1920. A few states, such as Washington, provide a state-run system allowing the collection of data and the targeting of research goals. The compensation laws varied widely from state to state, were generally not well enforced, and omitted many workers, such as agricultural workers, from coverage. Only railway, longshore and harbour workers, and federal employees have national worker’s compensation systems.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the federal role in occupational safety and health was largely restricted to research and consultation. In 1910 the Federal Bureau of Mines was established in the Department of the Interior to investigate accidents; consult with industry; conduct safety and production research; and provide training in accident prevention, first aid and mine rescue. The Office of Industrial Hygiene and Sanitation was created in the Public Health Service in 1914 to conduct research and assist states in solving occupational safety and health problems. It was located in Pittsburgh because of its close association with the Bureau of Mines and its focus on injuries and illnesses in the mining and steel industries.

In 1913 a separate Department of Labor was established; the Bureau of Labor Standards and the Interdepartmental Safety Council were organized in 1934. In 1936, the Department of Labor began to assume a regulatory role under the Walsh-Healey Public Contracts Act, which required certain federal contractors to meet minimum safety and health standards. Enforcement of these standards was often carried out by the states with varying degrees of effectiveness, under cooperative agreements with the Department of Labor. There were many who felt that this patchwork of state and federal laws was not effective in preventing workplace injuries and illnesses.

The Modern Era

The first comprehensive federal occupational safety and health laws were passed in 1969 and 1970. In November 1968, an explosion in Farmington, West Virginia, killed 78 coalminers, providing impetus to the demands of the miners for tougher federal legislation. In 1969, the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act was passed, which set mandatory health and safety standards for underground coal mines. The Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977 combined and expanded the 1969 Coal Mine Act with other earlier mining laws and created the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) to establish and enforce safety and health standards for all mines in the United States.

It was not a single disaster, but a steady rise in injury rates during the 1960s that helped spur passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. An emerging environmental consciousness and a decade of progressive legislation secured the new omnibus act. The law covers the majority of workplaces in the United States. It established the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in the Department of Labor to set and enforce federal workplace safety and health standards. The law was not a complete break from the past in that it contained a mechanism by which states could administer their own OSHA programmes. The Act also established the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), in what is now the Department of Health and Human Services, to conduct research, train safety and health professionals and develop recommended safety and health standards.

In the United States today, occupational safety and health services are the divided responsibility of a number of different sectors. In large companies, services for treatment, prevention and education are primarily provided by corporate medical departments. In smaller companies, these services are usually provided by hospitals, clinics or physicians’ offices.

Toxicological and independent medical evaluations are provided by individual practitioners as well as academic and public sector clinics. Finally, governmental entities provide for the enforcement, research funding, education and standard setting mandated by occupational safety and health laws.

This complex system is described in the following articles. Drs. Bunn and McCunney from the Mobil Oil Corporation and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, respectively, report on corporate services. Penny Higgins, RN, BS, of Northwest Community Healthcare in Arlington Heights, Illinois, delineates the hospital-based programmes. The academic clinic activities are reviewed by Dean Baker, MD, MPH, the Director of the University of California, Irvine’s Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health. Dr. Linda Rosenstock, Director of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and Sharon L. Morris, Assistant Chair for Community Outreach of the University of Washington’s Department of Environmental Health, summarize government activities at the federal, state and local levels. LaMont Byrd, the Director of Health and Safety for the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, AFL-CIO, describes the various activities provided to the membership of this international union by his office.

This division of responsibilities in occupational health often leads to overlapping, and in the case of workers’ compensation, inconsistent requirements and services. This pluralistic approach is both the strength and weakness of the system in the United States. It promotes multiple approaches to problems, but it can confuse all but the most sophisticated user. It is a system that often is in flux, with the balance of power shifting back and forth among the key players—private industry, labour unions, and state or federal governments.

Accident Insurance and Occupational Health Services in Germany

Every employer is contractually obligated to take precautions to guarantee the safety of his employees. The labour-related rules and regulations to which attention must be paid are of necessity just as various as the dangers present in the workplace. For this reason, the Occupational Safety Act (ASiG) of the Federal Republic of Germany includes among the duties of employers a legal obligation to consult specialist professionals on matters of occupational safety. This means that the employer is required to appoint not only specialist staff (particularly for technical solutions) but also company doctors for medical aspects of occupational safety.

The Occupational Safety Act has been in effect since December 1973. There were in the FRG at that time only about 500 doctors trained in what was called occupational medicine. The system of statutory accident insurance has played a decisive role in the development and construction of the present system, by means of which occupational medicine has established itself in companies in the persons of company doctors.

Dual Occupational Health and Safety System in the Federal Republic of Germany

As one of five branches of social insurance, the statutory accident insurance system makes a priority the task of taking all appropriate measures to ensure prevention of work accidents and occupational diseases through detection and elimination of work-related health hazards. In order to fulfil this legal mandate, legislators have granted extensive authority to a self-governing accident insurance system to enact its own rules and regulations concretizing and shaping the requisite preventive precautions. For this reason, the statutory accident insurance system has—within the bounds of existing public law—taken over the role of determining when an employer is required to take on a company doctor, what expert qualifications in occupational medicine the employer may demand of the company doctor and how much time the employer may estimate that the doctor will have to spend on the care of his employees.

The first draft of this accident prevention regulation dates from 1978. At that time, the number of available doctors with expertise in occupational medicine did not appear sufficient to provide all businesses with the care of company doctors. Thus the decision was made at first to establish concrete conditions for the larger businesses. At that time, to be sure, the businesses belonging to large-scale industry had often already made their own arrangements for company doctors, arrangements which already met or even exceeded the requirements stated in the accident prevention regulations.

Employment of a Company Doctor

The hours allocated in firms for the care of employees—called assignment times—are established by the statutory accident insurance system. Knowledge available to insurers concerning the existing risks to health in the various branches formed the basis for the calculation of the assignment times. The classification of firms with regard to particular insurers and the evaluation of possible health risks undertaken by them were thus the basis for the assignment of a company doctor.

Since the care rendered by company doctors is an occupational safety measure, the employer must cover the costs of assignment for such doctors. The number of employees within each of the several areas of hazard multiplied by the time allocated for care determine the sum of financial expenses. The result is a range of different forms of care, since it can pay—depending on the size of a firm—either to employ a doctor or doctors full-time, that is as the company’s own, or part-time, with services rendered on an hourly basis. This variety of requirements has led to a variety of organizational forms in which occupational medical services are offered.

The Duties of a Company Doctor

In principle, a distinction should be made, for legal reasons, between the provisions made by companies to provide care for employees and the work done by the doctors in the public health system responsible for the general medical care of the population.

In order to differentiate clearly which services of occupational medicine employers are responsible for, which are given in figure 1, the Occupational Safety Act has already anchored in law a catalogue of duties for company doctors. The company doctor is not subject to the orders of the employer in the fulfilment of these tasks; still, company doctors have had to fight the image of an employer-appointed doctor up to the present day.

Figure 1. The duties of occupational physicians employed by companies in Germany

One of the essential duties of the company doctor is the occupational medical examination of employees. This examination can become necessary according to the specific features of a given concern, if particular working conditions exist which lead the company doctor to offer, of his own accord, an examination to the employees involved. He cannot, however, force an employee to allow himself to be examined by him, but must rather convince him through trust.

Special Preventive Checkups in Occupational Medicine

There exists, in addition to this kind of examination, the special preventive check-up, participation in which by the employee is expected by the employer on legal grounds. These special preventive checkups end in the issuance of a doctor’s certificate, in which the examining doctor certifies that, based on the examination conducted, he has no objection to the employee’s engaging in work at the workplace in question. The employer may assign the employee only once for each certificate issued.

Special preventive checkups in occupational medicine are legally prescribed if exposure to particular hazardous materials occurs in the workplace or if particular hazardous activities belong to job practice and such health risks cannot be excluded through appropriate occupational safety precautions. Only in exceptional circumstances—as is the case, for example, with radiation protection checkups—is the legal requirement that an examination be performed supplemented by legal regulations concerning what the doctor carrying out the examination must pay attention to, which methods he must apply, which criteria he must use to interpret the outcome of the examination and which criteria he must apply in judging health status with regard to work assignments.

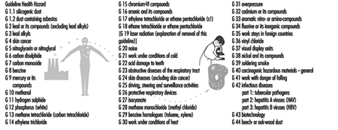

This is why in 1972 the Berufsgenossenschaften, made up of commercial trade associations which provide the accident insurance for trade and industry, authorized a committee of experts to work out commensurate recommendations to doctors working in occupational medicine. Such recommendations have existed for more than 20 years. The Berufsgenossenschaften Guidelines for Special Preventive Checkups, listed in figure 2, now show a total of 43 examination procedures for the various health hazards which can be countered, on the grounds of present knowledge, with appropriate medical precautionary measures so as to prevent diseases from developing.

Figure 2. A summary information on external services of the Berufgenossenschaften in the German building industry

The Berufsgenossenschaften deduce the mandate to make available such recommendations from their duty to take all appropriate measures to prevent occupational diseases from arising. These Guidelines for Special Preventive Checkups are a standard work in the field of occupational medicine. They find application in all spheres of activity, not only in enterprises in the sphere of trade and industry.

In connection with the provision of such occupational medical recommendations, the Berufsgenossenschaften also took steps early on to ensure that in businesses lacking their own company doctor the employer would be required to arrange for these preventive checkups. Subject to certain basic requirements having to do primarily with the specialized knowledge of the doctor, but also with the facilities available in his or her practice, even doctors without expertise in occupational medicine can acquire the authority to offer companies their services in performing preventive checkups, contingent on a policy administered by the Berufsgenossenschaften. This was the precondition for the current availability of the total of 13,000 authorized doctors in Germany who perform the 3.8 million preventive checkups performed annually.

It was the supply of a sufficient number of doctors that also made it possible legally to require that employers initiate these special preventive checkups in complete independence of the question of whether or not the company employs a doctor prepared to do such checkups. In this way, it became possible to use the statutory accident insurance system to ensure enforcement of certain measures of health protection at work, even at the level of small businesses. The relevant legal regulations may be found in the Ordinance on Hazardous Substances and, comprehensively, in the accident prevention regulation, which regulates the rights and duties of the employer and the examined employee and the function of the licensed doctor.

Care Provided by Company Doctors

The statistics released annually by the Federal Board of Doctors (Bundesärztekammer) show that for the year 1994 more than 11,500 doctors fulfil the prerequisites, in the form of specialist knowledge in industrial medicine, to be company doctors (see table 1). In the Federal Republic of Germany, the organization Standesvertretung representing the medical profession regulates autonomously which qualifications must be met by doctors as regards study and subsequent professional development before they may become active as doctors in a given field of medicine.

Table 1. Doctors with specialist knowledge in occupational medicine

|

Number* |

Percentage* |

|

|

Field designation “occupational medicine” |

3,776 |

31.4 |

|

Additional designation “corporate medicine” |

5,732 |

47.6 |

|

Specialist knowledge in occupational medicine |

2,526 |

21.0 |

|

Total |

12,034 |

100 |

* As of 31 December 1995.

The satisfaction of these prerequisites for the activity of a company doctor represents either the attainment of the field designation “occupational medicine” or of the additional designation “corporate medicine”—that is, either four years’ further study after the licence to practice in order to be active exclusively as a work physician, or three years’ further study, after which activity as a company doctor is allowed only in so far as it is connected with medical activity in another field (e.g., as an internist). Doctors tend to prefer the second variant. This means, however, that they themselves see the chief emphasis of their professional work as physicians in a classical field of medical activity, not in occupational medical practice.

For these doctors, occupational medicine has the significance of an auxiliary source of income. This explains at the same time why the medical element of the examination by doctors continues to dominate the practical exercise of the profession of company doctor, although the legislature and the statutory accident insurance system themselves emphasize inspection of companies and medical advice given to employers and employees.

In addition, there still exists a group of doctors who, having acquired specialist knowledge in occupational medicine in earlier years, met different requirements at that time. Of particular significance in this regard are the standards which doctors in the former German Democratic Republic were required to meet in order to be allowed to practice as company doctors.

Organization of Care Provided by Company Doctors

In principle, it is left up to the employer to choose freely a company doctor for the firm from among those offering occupational medical services. Since this supply was not yet available subsequent to the establishment, in the early 1970s, of the relevant legal preconditions, the statutory accident insurance system took the initiative in regulating the market economy of supply and demand.

The Berufsgenossenschaften of the building industry instituted their own occupational medical services by engaging doctors with specialist knowledge in occupational medicine in contracts to provide care, as company doctors, to the firms affiliated with them. Via their statutes, the Berufsgenossenschaften arranged for each of their firms to be cared for by its own occupational medical service. The costs incurred were distributed among all the firms through appropriate forms of financing. A summary of information concerning external occupational medical services of the Berufsgenossenschaften of the building industry is given in table 2.

Table 2. Company medical care provided by external occupational medical services,1994

|

Doctors providing care as primary occupation |

Doctors providing care as secondary occupation |

Centres |

Employees cared for |

|

|

ARGE Bau1 |

221 |

83 mobile: 46 |

||

|

BAD2 |

485 |

72 |

175 mobile: 7 |

1.64 million |

|

IAS3 |

183 |

58 |

500,000 |

|

|

TÜV4 |

72 |

|||

|

AMD Würzburg5 |

60–70 |

30–35 |

1 ARGE Bau = Workers’ Community of the Berufgenossenschaften of Building Industry Trade Associations.

2 BAD = Occupational Medical Service of the Berufgenossenschaften.

3 IAS = Institute for Occupational and Social Medicine.

4 TÜV = Technical Control Association.

5 AMD Würzburg = Occupational Medical Service of the Berufgenossenschaften.

The Berufsgenossenschaften for the maritime industry and that for domestic shipping also founded their own occupational medical services for their businesses. It is a characteristic of all of them that the idiosyncrasies of the businesses in their trade—non-stationary enterprises with special vocational requirements—were a decisive factor in their taking the initiative to make clear to their companies the necessity for company doctors.

Similar considerations occasioned the remaining Berufsgenossenschaften to unite themselves in a confederation in order to found the Occupational Medical Service of the Berufsgenossenschaften (BAD). This service organization, which offers its services to every enterprise in the market, was enabled at an early stage by the financial collateral provided by the Berufsgenossenschaften to be present over the entire area of the Federal Republic of Germany. Its broad coverage, as far as representation goes, was meant to ensure that even those businesses located in the Federal states, or states of relatively poor economic activity, of the Federal Republic would have access to a company doctor in their area. This principle has been maintained up to the present time. The BAD is considered, meanwhile, the largest provider of occupational medical services. Nonetheless, it is forced by the market economy to assert itself against competition from other providers, particularly within urban agglomerations, by maintaining a high level of quality in what it provides.

The occupational medical services of the Technical Control Association (TÜV) and of the Institute for Occupational and Social Medicine (IAS) are the second- and third-largest transregional providers. There are in addition numerous smaller, regionally active enterprises in all of the Federated States of Germany.

Cooperation with Other Providers of Services in Occupational Health and Safety

The Occupational Safety Act, as a legal foundation for care provided to companies by company doctors, provides also for professional supervision of occupational safety, particularly in order to ensure that aspects of occupational safety be handled by personnel schooled in technical precautions. The requirements of industrial practice have changed meanwhile to such an extent that technical knowledge regarding questions of occupational safety must now be supplemented more and more by familiarity with questions of the toxicology of materials used. In addition, questions of ergonomic organization of work conditions and of the physiological effects of biological agents play an increasing role in evaluations of stresses in a place of work.

The requisite knowledge may be mustered only through interdisciplinary cooperation of experts in the field of health and safety at work. Therefore, the statutory accident insurance system supports particularly the development of forms of organization which take such interdisciplinary cooperation into account at the organizational stage, and creates within its own structure the preconditions for this cooperation by redesigning its administrative departments in a suitable fashion. What was once called the Technical Inspection Service of the statutory accident insurance system turns into a field of prevention, within which not only technical engineers but also chemists, biologists and, increasingly, physicians are active together in designing solutions for problems of labour safety.

This is one of the indispensable prerequisites for creating a basis for the type of organization of interdisciplinary cooperation—within businesses and between safety technology service organizations and company doctors—required for efficient solution of the immediate problems of occupational health and safety.

In addition, supervision in respect of safety technology should be advanced, in all companies, just as much as supervision by company doctors. Safety specialists are to be employed by businesses on the same legal basis—the Occupational Safety Act—or appropriately trained personnel affiliated with the industry are to be supplied by the businesses themselves. Just as in the case of the supervision provided by company doctors, the accident prevention regulation, Specialists for Occupational Safety (VBG 122), has formulated the requirements according to which businesses must employ safety specialists. In the case of safety-technical supervision of businesses as well, these requirements take all necessary precautions to incorporate each of the 2.6 million firms currently comprising the commercial economy as well as those in the public sector.

Around two million of these firms have fewer than 20 employees and are classed as small industry. With the full supervision of all enterprises, that is, including the smaller and smallest of businesses, the statutory accident insurance system creates for itself a platform for the establishment of occupational health and safety in all areas.

Occupational Health Services in Small-Scale Enterprises

The coverage of workers in small-scale enterprises (SSEs) is perhaps the most daunting challenge to systems for delivering occupational health services. In most countries, SSEs comprise the vast majority of the business and industrial undertakings—reaching as high as 90% in some of the developing and newly industrialized countries—and they are found in every sector of the economy. They employ on average nearly 40% of the workforce in the industrialized countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and up to 60% of the workforce in developing and newly industrialized countries. Although their workers are exposed to perhaps an even greater range of hazards than their counterparts in large enterprises (Reverente 1992; Hasle et al. 1986), they usually have little if any access to modern occupational health and safety services.

Defining Small-Scale Enterprises

Enterprises are categorized as small-scale on the basis of such characteristics as the size of their capital investment, the amount of their annual revenues or the number of their employees. Depending on the context, the number for the last category has ranged from one to 500 employees. In this article, the term SSE will be applied to enterprises having 50 or fewer employees, the most widely accepted definition (ILO 1986).

SSEs are gaining importance in national economies. They are employment-intensive, flexible in adapting to rapidly changing market situations, and provide job opportunities for many who would otherwise be unemployed. Their capital requirements are often low and they can produce goods and services near the consumer or client.

They also present disadvantages. Their lifetime is often brief, making their activities difficult to monitor and, frequently, their small margins of profits are achieved only at the expense of their workers (who are often also their owners) in terms of hours and intensity of workloads and exposure to occupational health risks.

The Workforce of SSEs