Warshaw, Leon J.

Address: Institute of Environmental Medicine, 180 West End Avenue #6C, New York, New York 10023-4926

Country: United States

Phone: 1 (212) 877-1060

E-mail: 76451.333@compuserve.com

Past position(s): Executive Director, New York Business Group on Health; Deputy Director for Health Affairs, New York City Mayor's Office of Operations; Vice-President, Corporate Medical Director, Equitable Life Assurance Society of the US

Areas of interest: Organization of occupational health services; health promotion; stress; violence in the; workplace

Health Care: Its Nature and its Occupational Health Problems

Health care is a labour intensive industry and, in most countries, health care workers (HCWs) constitute a major sector of the workforce. They comprise a wide range of professional, technical and support personnel working in a large variety of settings. In addition to health professionals, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, social workers and others involved in clinical services, they include administrative and clerical personnel, housekeeping and dietary staff, laundry workers, engineers, electricians, painters and maintenance workers who repair and refurbish the building and the equipment it contains. In contrast with those providing direct care, these support workers usually have only casual, incidental contact with patients.

HCWs represent diverse educational, social and ethnic levels and are usually predominantly female. Many, particularly in home care, are employed in entry-level positions and require considerable basic training. Table 1 lists samples of health care functions and associated occupations.

Table 1. Examples of health care functions and associated occupations

|

Functions |

Occupational category * |

Specific occupations |

|

Direct patient care |

Health-diagnosing occupations |

Physicians |

|

Technical support |

Health technicians |

Clinical laboratory technicians |

|

Services |

Health services |

Dental assistants |

|

Administrative support |

Clerical services |

Billing clerks |

|

Research |

Scientific occupations |

Scientists and research |

* Occupational categories are, in part, adapted from those used by the US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

A segment of the health sector (unfortunately, often too small and under-resourced in most communities) is devoted to direct and indirect preventive services. The major focus of the health care industry, however, is the diagnosis, treatment and care of the sick. This creates a special set of dynamics, for the sick exhibit varying levels of physical and emotional dependencies that set them apart from the customers in such personal services industries as, for example, retail trade, restaurants and hotels. They require, and traditionally receive, special services and considerations, often on an emergency basis, provided frequently at the expense of the HCWs’ personal comfort and safety.

Reflecting their size and numbers of employees, acute and long-term care facilities constitute perhaps the most prominent elements in the health care industry. They are supplemented by outpatient clinics, “surgicenters” (facilities for outpatient surgery), clinical and pathological laboratories, pharmacies, x-ray and imaging centres, ambulance and emergency care services, individual and group offices, and home care services. These may be located within a hospital or operated elsewhere under its aegis, or they may be free-standing and operated independently. It should be noted that there are profound differences in the way health services are delivered, ranging from the well-organized, “high tech” care available in urban centres in developed countries to the underserved areas in rural communities, in developing countries and in inner-city enclaves in many large cities.

Superimposed on the health care system is a massive educational and research establishment in which students, faculty, researchers and support staffs often come in direct contact with patients and participate in their care. This comprises schools of medicine, dentistry, nursing, public health, social work and the variety of technical disciplines involved in health care.

The health care industry has been undergoing profound changes during the past few decades. Ageing of the population, especially in developed countries, has amplified the use of nursing homes, domiciliary facilities and home care services. Scientific and technological developments have not only led to the creation of new types of facilities staffed by new classes of specially-trained personnel, but they have also de-emphasized the role of the acute care hospital. Now, many services requiring inpatient care are being provided on an ambulatory basis. Finally, fiscal constraints dictated by the continuing escalation of health care costs have been reconfiguring the health care industry, at least in developing countries, resulting in pressure for cost-containment to be achieved through changes in the organization of health care services.

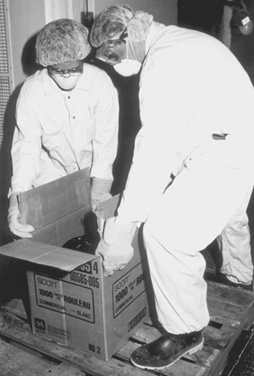

HCWs who are in direct contact with the sick, wherever they work, are exposed to a number of unique hazards. They face the risk of acquiring infections from the patients they serve, as well as the risk of musculoskeletal injuries when lifting, transferring or restraining them. Support staff not directly involved in patient care (e.g., laundry and housekeeping and materials handling workers) are not only routinely exposed to chemicals, such as cleaning agents and disinfectants of industrial strength, but are also exposed to biological hazards from contaminated linens and wastes (see figure 1). There is also the ethos of health care which, especially in emergency situations, requires HCWs to put the safety and comfort of their patients above their own. Coping with the stress of therapeutic failures, death and dying often takes its toll in worker burnout. All this is compounded by shift work, deliberate or inadvertent understaffing and the necessity of catering to the sometimes unreasonable demands from patients and their families. Finally, there is the threat of abuse and violence from patients, particularly when the job requires them to work alone or takes them into unsafe areas. All these are described in greater detail in other articles in this chapter and elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia.

Figure 1. Handling contaminated biological material

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) reported that needle punctures, musculoskeletal sprains and back injuries probably were the most common injuries in the health care industry (Wugofski 1995). The World Health Organization (WHO) Conference on Occupational Hazards in 1981 identified as its five main areas of concern:

- cuts, lacerations and fractures

- back injuries

- lack of personal safety equipment

- poor maintenance of mechanical and electrical systems

- assault by patients.

Are they health care workers, too?

Often overlooked when considering the safety and well-being of health care workers are students attending medical, dental, nursing and other schools for health professionals and volunteers serving pro bono in healthcare facilities. Since they are not “employees” in the technical or legal sense of the term, they are ineligible for workers’ compensation and employment-based health insurance in many jurisdictions. Health care administrators have only a moral obligation to be concerned about their health and safety.

The clinical segments of their training bring medical, nursing and dental students into direct contact with patients who may have infectious diseases. They perform or assist in a variety of invasive procedures, including taking blood samples, and often do laboratory work involving body fluids and specimens of urine and faeces. They are usually free to wander about the facility, entering areas containing potential hazards often, since such hazards are rarely posted, without an awareness of their presence. They are usually supervised very loosely, if at all, while their instructors are often not very knowledgeable, or even interested, in matters of safety and health protection.

Volunteers are rarely permitted to participate in clinical care but they do have social contacts with patients and they usually have few restrictions with respect to areas of the facility they may visit.

Under normal circumstances, students and volunteers share with health care workers the risks of exposure to potentially harmful hazards. These risks are exacerbated at times of crisis and in emergencies when they step into or are ordered into the breech. Clearly, even though it may not be spelled out in laws and regulations or in organizational procedure manuals, they are more than entitled to the concern and protection extended to “regular” health care workers.

Leon Warshaw

Biological Hazards

Biological hazards, which pose a risk for infectious disease, are common throughout the world, but they are particularly problematic in developing countries. While the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a nearly universal threat to HCWs, it is particularly important in African and Asian countries where this virus is endemic. As discussed later in this chapter, the risk of HBV transmission after percutaneous exposure to hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive blood is approximately 100-fold higher than the risk of transmitting the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) through percutaneous exposure to HIV-infected blood (i.e., 30% versus 0.3%). Nonetheless, there has indeed been an evolution of concern regarding parenteral exposure to blood and body fluids from the pre-HIV to the AIDS era. McCormick et al. (1991) found that the annual reported incidents of injuries from sharp instruments increased more than threefold during a 14-year period and among medical house officers the reported incidents increased ninefold. Overall, nurses incur approximately two-thirds of the needlestick injuries reported. Yassi and McGill (1991) also noted that nursing staff, particularly nursing students, are at highest risk for needlestick injuries, but they also found that approximately 7.5% of medical personnel reported exposures to blood and body fluids, a figure that is probably low because of underreporting. These data were consistent with other reports which indicated that, while there is increased reporting of needlesticks reflecting concerns about HIV and AIDS, certain groups continue to underreport. Sterling (1994) concludes that underreporting of needlestick injuries ranges from 40 to 60%.

Certain risk factors clearly enhance the likelihood of transmission of bloodborne diseases; these are discussed in the article “Prevention of occupational transmission of bloodborne pathogens”. Frequent exposure has indeed been associated with high seroprevalence rates of hepatitis B among laboratory workers, surgeons and pathologists. The risk of hepatitis C is also increased. The trend towards greater attention to prevention of needlestick injuries is, however, also noteworthy. The adoption of universal precautions is an important advance. Under universal precautions, it is assumed that all blood-containing fluid is potentially infectious and that appropriate safeguards should always be invoked. Safe disposal containers for needles and other sharp instruments are increasingly being placed in conveniently accessible locations in treatment areas, as illustrated in figure 2. The use of new devices, such as the needle-less access system for intravenous treatment and/or blood sampling has been shown to be a cost-effective method of reducing needlestick injuries (Yassi and McGill 1995).

Figure 2. Disposal container for sharp instruments and devices

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Blood and body fluids are not the only source of infection for HCWs. Tuberculosis (TB) is also on the rise again in parts of the world where previously its spread had been curtailed and, as discussed later in this chapter, is a growing occupational health concern. In this, as in other nosocomial infections, such concern is heightened by the fact that so many of the organisms involved have become drug-resistant. There is also the problem of new outbreaks of deadly infectious agents, such as the Ebola virus. The article “Overview of infectious diseases” summarizes the major infectious disease risks for HCWs.

Chemical Hazards

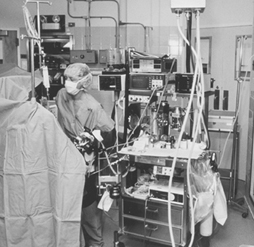

HCWs are exposed to a wide variety of chemicals, including disinfectants, sterilants, laboratory reagents, drugs and anaesthetic agents, to name just a few of the categories. Figure 3 shows a storage cabinet in an area of a large hospital where prosthetics are fabricated and clearly illustrates the vast array of chemicals that are present in health care facilities. Some of these substances are highly irritating and may also be sensitizing. Some disinfectants and antiseptics also tend to be quite toxic, also with irritating and sensitizing propensities that may induce skin or respiratory tract disease. Some, like formaldehyde and ethylene oxide, are classified as mutagens, teratogens and human carcinogens as well. Prevention depends on the nature of the chemical, the maintenance of the apparatus in which it is used or applied, environmental controls, worker training and, in some instances, the availability of correct personal protective equipment. Often such control is straightforward and not very expensive. For example, Elias et al. (1993) showed how ethylene oxide exposure was controlled in one health care facility. Other articles in this chapter address chemical hazards and their management.

Figure 3. Storage cabinet for hazardous chemicals

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Physical Hazards and the Building Environment

In addition to the specific environmental contaminants faced by HCWs, many health care facilities also have documented indoor air quality problems. Tran et al. (1994), in studying symptoms experienced by operating room personnel, noted the presence of the “sick building syndrome” in one hospital. Building design and maintenance decisions are, therefore, extremely important in health care facilities. Particular attention must be paid to correct ventilation in specific areas such as laboratories, operating rooms and pharmacies, the availability of hoods and avoidance of the insertion of chemical-laden fumes into the general air-conditioning system. Controlling the recirculation of air and using special equipment (e.g., appropriate filters and ultraviolet lamps) is needed to prevent the transmission of air-borne infectious agents. Aspects of the construction and planning of health care facilities are discussed in the article “Buildings for health care facilities”.

Physical hazards are also ubiquitous in hospitals (see “Exposure to physical agents” in this chapter). The wide variety of electrical equipment used in hospitals can present an electrocution hazard to patients and staff if not properly maintained and grounded (see figure 4). Especially in hot and humid environments, heat exposure may present a problem to workers in such areas as laundries, kitchens and boiler rooms. Ionizing radiation is a special concern for staff in diagnostic radiology (i.e., x ray, angiography, dental radiography and computerized axial tomography (CAT) scans) as well as for those in therapeutic radiology. Controlling such radiation exposures is a routine matter in designated departments where there is careful supervision, well-trained technicians and properly shielded and maintained equipment, but it can be a problem when portable equipment is used in emergency rooms, intensive care units and operating rooms. It can also be a problem to housekeeping and other support staff whose duties take them into areas of potential exposure. In many jurisdictions these workers have not been properly trained to avoid this hazard. Exposure to ionizing radiation may also present a problem in diagnostic and therapeutic nuclear medicine units and in preparing and distributing doses of radioactive pharmaceuticals. In some cases, however, radiation exposure remains a serious problem (see the article “Occupational health and safety practice: The Russian experience” in this chapter).

Figure 4. Electrical equipment in hospital

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Contradicting the prevailing impression of hospitals as quiet workplaces, Yassi et al. (1991) have documented the surprising extent of noise-induced hearing loss among hospital workers (see table 2). The article “Ergonomics of the physical work environment” in this chapter offers useful recommendations for controlling this hazard, as does table 3.

Table 2. 1995 integrated sound levels

|

Area monitored |

dBA (lex) Range |

|

Cast room |

76.32 to 81.9 |

|

Central energy |

82.4 to 110.4 |

|

Nutrition and food services (main kitchen) |

|

|

Housekeeping |

|

|

Laundry |

|

|

Linen service |

76.3 to 91.0 |

|

Mailroom |

|

|

Maintenance |

|

|

Materials handling |

|

|

Print shop |

|

|

Rehabilitation engineering |

|

Note: “Lex” means the equivalent sound level or the steady sound level in dBA which, if present in a workplace for 8 hours, would contain the same acoustic energy.

Table 3. Ergonomic noise reduction options

|

Work area |

Process |

Control options |

|

Central energy |

General area |

Enclose the source |

|

Dietetics |

Pot washer |

Automate process |

|

Housekeeping |

Burnishing |

Purchasing criteria |

|

Laundry |

Dryer/washer |

Isolate and reduce vibration |

|

Mailroom |

Tuberoom |

Purchasing criteria |

|

Maintenance |

Various equipment |

Purchasing criteria |

|

Materiel handling and |

Carts |

Maintenance |

|

Print shop |

Press operator |

Maintenance |

|

Rehabilitation |

Orthotics |

Purchasing criteria |

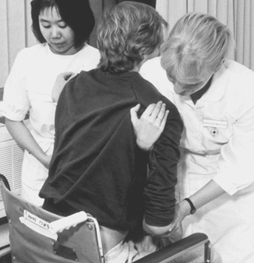

By far the most common and most costly type of injury faced by HCWs is back injury. Nurses and attendants are at greatest risk of musculoskeletal injuries due to the large amount of patient lifting and transferring that their jobs require. The epidemiology of back injury in nurses was summarized by Yassi et al. (1995a) with respect to one hospital. The pattern they observed mirrors those that have been universally reported. Hospitals are increasingly turning to preventive measures which may include staff training and the use of mechanical lifting devices. Many are also providing up-to-date diagnostic, therapeutic and rehabilitation health services that will minimize lost time and disability and are cost-effective (Yassi et al. 1995b). Hospital ergonomics has taken on increasing importance and, therefore, is the subject of a review article in this chapter. The specific problem of the prevention and management of back pain in nurses as one of the most important problems for this cohort of HCWs is also discussed in the article “Prevention and management of back pain in nurses” in this chapter. Table 4 lists the total number of injuries in a one-year period.

Table 4. Total number of injuries, mechanism of injury and nature of industry (one hospital, all departments), 1 April 1994 to 31 March 1995

|

Nature of injury sustained |

Total |

||||||||||||

|

Mechanism |

Blood/ |

Cut/ |

Bruise/ |

Sprain/ |

Fracture/ |

Burn/ |

Human |

Broken |

Head- |

Occupa- |

Other3 |

Un- |

|

|

Exertion |

|||||||||||||

|

Transferring |

105 |

105 |

|||||||||||

|

Lifting |

83 |

83 |

|||||||||||

|

Assisting |

4 |

4 |

|||||||||||

|

Turning |

27 |

27 |

|||||||||||

|

Breaking fall |

28 |

28 |

|||||||||||

|

Pushing |

1 |

25 |

26 |

||||||||||

|

Lifting |

1 |

52 |

1 |

54 |

|||||||||

|

Pulling |

14 |

14 |

|||||||||||

|

Combination- |

38 |

38 |

|||||||||||

|

Other |

74 |

74 |

|||||||||||

|

Fall |

3 |

45 |

67 |

3 |

1 |

119 |

|||||||

|

Struck/ |

66 |

76 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

152 |

||||||

|

Caught in/ |

13 |

68 |

8 |

1 |

1 |

91 |

|||||||

|

Exp. |

3 |

1 |

4 |

19 |

16 |

12 |

55 |

||||||

|

Staff abuse |

|||||||||||||

|

Patient |

16 |

11 |

51 |

28 |

8 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

120 |

||||

|

Spill/splashes |

80 |

1 |

81 |

||||||||||

|

Drug/ |

2 |

2 |

|||||||||||

|

Exp. |

5 |

5 |

10 |

||||||||||

|

Needlesticks |

159 |

22 |

181 |

||||||||||

|

Scalpel cuts |

34 |

14 |

48 |

||||||||||

|

Other5 |

3 |

1 |

29 |

1 |

6 |

40 |

|||||||

|

Unknown (no |

8 |

8 |

|||||||||||

|

Total |

289 |

136 |

243 |

558 |

5 |

33 |

8 |

7 |

19 |

25 |

29 |

8 |

1,360 |

1 No blood/body fluid. 2 This includes rashes/dermatitis/work-related illness/burning eyes, irritated eyes. 3 Exposure to chemical or physical agents but with no documented injuries affects. 4 Accident not reported. 5 Exposure to cold/heat, unknown.

In discussing musculoskeletal and ergonomic problems, it is important to note that while those engaged in direct patient care may be at greatest risk (see figure 5) many of the support personnel in hospital must contend with similar ergonomic burdens (see figure 6 and figure 7). The ergonomic problems facing hospital laundry workers have been well-documented (Wands and Yassi 1993) (see figure 8, figure 9 and figure 10) and they also are common among dentists, otologists, surgeons and especially microsurgeons, obstetricians, gynaecologists and other health personnel who often must work in awkward postures.

Figure 5. Patient lifting is an ergonomic hazard in most hospitals

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Figure 6. Overhead painting: A typical ergonomic hazard for a tradesworker

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Figure 7. Cast-making involves many ergonomic stresses

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Figure 8. Laundry work such as this can cause repetitive stress injury to the upper limbs

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Figure 9. This laundry task requires working in an awkward position

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Figure 10. A poorly designed laundry operation can cause back strain

Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Organizational Problems

The article “Strain in health care work” contains a discussion of some of the organizational problems in hospitals and a summary of the principal findings of Leppanen and Olkinuora (1987), who reviewed Finnish and Swedish studies of stress among HCWs. With the rapid changes currently under way in this industry, the extent of alienation, frustration and burnout among HCWs is considerable. Added to that is the prevalence of staff abuse, an increasingly troublesome problem in many facilities (Yassi 1994). While it is often thought that the most difficult psychosocial problem faced by HCWs is dealing with death and dying, it is being recognized increasingly that the nature of the industry itself, with its hierarchical structure, its growing job insecurity and the high demands unsupported by adequate resources, is the cause of the variety of stress-related illness faced by HCWs.

The Nature of the Health Care Sector

In 1976, Stellman wrote, “If you ever wondered how people can manage to work with the sick and always stay healthy themselves, the answer is that they can’t” (Stellman 1976). The answer has not changed, but the potential hazards have clearly expanded from infectious diseases, back and other injuries, stress and burnout to include a large variety of potentially toxic environmental, physical and psychosocial exposures. The world of the HCW continues to be largely unmonitored and largely unregulated. None the less, progress is being made in addressing occupational health and safety hazards in hospitals. The International Commission on Occupational Health (ICOH) has a sub-committee addressing this problem, and several international conferences have been held with published proceedings that offer useful information (Hagberg et al. 1995). The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and NIOSH have proposed guidelines to address many of the problems of the health care industry discussed in this article (e.g., see NIOSH 1988). The number of articles and books addressing health and safety issues for HCWs has been growing rapidly, and good overviews of health and safety in the US health care industry have been published (e.g., Charney 1994; Lewy 1990; Sterling 1994). The need for systematic data collection, study and analysis regarding hazards in the health care industry and the desirability of assembling interdisciplinary occupational health teams to address them have become increasingly evident.

When considering occupational health and safety in the health care industry, it is crucial to appreciate the enormous changes currently taking place in it. Health care “reform”, being instituted in most of the developed countries of the world, is creating extraordinary turbulence and uncertainty for HCWs, who are being asked to absorb rapid changes in their work tasks often with greater exposure to risks. The transformation of health care is spurred, in part, by advances in medical and scientific knowledge, the development of innovative technological procedures and the acquisition of new skills. It is also being driven, however, and perhaps to an even greater extent, by concepts of cost-effectiveness and organizational efficiency, in which “downsizing” and “cost control” have often seemed to become goals in themselves. New institutional incentives are being introduced at different organizational levels in different countries. The contracting out of jobs and services that had traditionally been carried out by a large stable workforce is now increasingly becoming the norm. Such contracting out of work is reported to have helped the health administrators and politicians achieve their long-term goal of making the process of health care more flexible and more accountable. These changes have also brought changes in roles that were previously rather well-defined, undermining the traditional hierarchical relationships among planners, administrators, physicians and other health professionals. The rise of investor-owned health care organizations in many countries has introduced a new dynamic in the financing and management of health services. In many situations, HCWs have been forced into new working relationships that involve such changes as downgrading services so that they can be performed by less-skilled workers at lower pay, reduced staffing levels, staff redeployments involving split shifts and part-time assignments. At the same time, there has been a slow but steady growth in the numbers of such physician surrogates as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, midwives and psychiatric social workers who command lower rates of pay than the physicians they are replacing. (The ultimate social and health costs both to HCWs and to the public, as patients and payers, is still to be determined.)

A growing trend in the US that is also emerging in the UK and northern European countries is “managed care”. This generally involves the creation of organizations paid on a per capita basis by insurance companies or government agencies to provide or contract for the provision of a comprehensive range of health services to a voluntarily-enrolled population of subscribers. Their aim is to reduce the costs of health care by “managing” the process: using administrative procedures and primary care physicians as “gatekeepers” to control the utilization of expensive in-patient hospital days, reducing referrals to high-priced specialists and use of costly diagnostic procedures, and denying coverage for expensive new forms of “experimental” treatment. The growing popularity of these managed care systems, fuelled by aggressive marketing to employer- and government-sponsored groups and individuals, has made it difficult for physicians and other health care providers to resist becoming involved. Once engaged, there is a variety of financial incentives and disincentives to influence their judgement and condition their behaviour. The loss of their traditional autonomy has been particularly painful for many medical practitioners and has had a profound influence on their patterns of practice and their relationships with other HCWs.

These rapid changes in the organization of the health care industry are having profound direct and indirect effects on the health and safety of HCWs. They affect the ways health services are organized, managed, delivered and paid for. They affect the ways HCWs are trained, assigned and supervised and the extent to which considerations of their health and safety are addressed. This should be kept in mind as the various occupational health hazards faced by HCWs are discussed in this chapter. Finally, although it may not appear to be directly relevant to the content of this chapter, thought should be given to the implications of the well-being and performance of HCWs to the quality and effectiveness of the services they provide to their patients.

Precarious Employment and Child Labour

The section of this article devoted to child labour is based largely on the report of the ILO Committee on Employment and Social Policy: Child Labour, GB.264/ESP/1, 264th Session, Geneva, November 1995

Throughout the world, not only in the developing but also in the industrialized countries, there are many millions of workers whose employment may be termed precarious from the standpoint of its potential effect on their health and well-being. They may be divided into a number of non-exclusive categories based on the kinds of work they perform and the types of relationship to their jobs and to their employers, such as the following:

- child labourers

- contract labourers

- enslaved and bonded workers

- informal sector workers

- migrant workers

- piece-workers

- unemployed and underemployed workers.

Their common denominators include: poverty; lack of education and training; exposure to exploitation and abuse; ill health and lack of adequate medical care; exposure to health and safety hazards; lack of protection by governmental agencies even where laws and regulations have been articulated; lack of social welfare benefits (e.g., minimum wages, unemployment insurance, health insurance and pensions); and lack of an effective voice in movements to improve their lot. In large part, their victimization stems from the poverty and the lack of education/training that force them to take whatever kind of work may be available. In some areas and in some industries, the existence of these classes of workers is fostered by explicit economic and social policies of the government or, even where they have been prohibited by local laws and/or endorsement of international Conventions, by the deliberate inattention of governmental regulatory agencies. The costs to these workers and their families in terms of ill-health, shortened life-expectancy and impact on well-being are imponderable; they often extend from one generation to the next. By any sort of measure, they may be considered disadvantaged.

The exploitation of labour is also one deleterious aspect of the global economy wherein the most dangerous and precarious work is transferred from the richer countries to the poorer ones. Thus, precarious employment can and should be viewed in macro-economic terms as well. This is discussed more fully elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia.

This article briefly summarizes the characteristics of the more important of these employment categories and their effects on workers’ health and well-being.

Migrant Workers

Migrant workers often represent a critically important segment of a country’s labour force. Some bring developed skills and professional competencies that are in short supply, particularly in areas of rapid industrial growth. Typically, however, they perform the unskilled and semi-skilled, low-paying jobs that are scorned by workers native to the area. These include “stooped labour” such as cultivating and harvesting crops, manual labour in the construction industry, menial services such as cleaning and refuse removal, and poorly remunerative repetitive jobs such as those in “sweatshops” in the apparel industry or on assembly-line work in light industries.

Some migrant workers find jobs in their own countries, but, more recently, they are for the most part “external” workers in that they come from another, usually less-developed country. Thus, they make unique contributions to the economy of two nations: by doing necessary work in the country in which they are working, and by their remittances of “hard” money to the families they leave behind in the country from which they came.

During the nineteenth century, large numbers of Chinese labourers were imported into the United States and Canada, for example, to work on the construction of the western portions of the transcontinental railroads. Later, during the Second World War, while American workers were serving in the armed forces or in the war industries, the United States reached a formal agreement with Mexico known as the Bracero Program (1942–1964) that provided millions of temporary Mexican workers for the vitally important agricultural industry. During the postwar period, “guest” workers from southern Europe, Turkey and North Africa helped to rebuild the war-ravaged countries of western Europe and, during the 1970s and 1980s, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the other newly rich oil-producing countries of the Near East imported Asians to build their new cities. During the early 1980s, external migrant workers accounted for approximately two-thirds of the workforces in the Arab Gulf states (citizen workers outnumbered the expatriates only in Bahrain).

Except for teachers and health workers, most of the migrants have been male. However, in most countries throughout these periods as families became wealthier, there has been an increasing demand for the importation of domestic workers, mostly women, to perform housework and provide care for infants and children (Anderson 1993). This has also been true in industrialized countries where increasing numbers of women were entering the workforce and needed household help to take up their traditional home-making activities.

Another example can be found in Africa. After the Republic of Transkei was created in 1976 as the first of the ten independent homelands called for in South Africa’s 1959 Promotion of Self-Government Act, migrant labour was its major export. Located on the Indian Ocean on the east coast of South Africa, it sent about 370,000 Xhosa males, its dominant ethnic group, as migrant workers to neighbouring South Africa, a number representing approximately 17% of its total population.

Some migrant workers have visas and temporary work permits, but these are often controlled by their employers. This means that they cannot change jobs or complain about mistreatment for fear that this will lead to revocation of their work permits and forced repatriation. Often, they evade the official immigration procedures of the host country and become “illegal” or “undocumented" workers. In some instances, migrant workers are recruited by labour “contractors” who charge exorbitant fees to smuggle them into the country to meet the needs of local employers. Fear of arrest and deportation, compounded by their unfamiliarity with the language, laws and customs of the host country, makes such workers particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

Migrant workers are frequently overworked, deprived of the benefit of proper tools and equipment, and often knowingly exposed to preventable health and safety hazards. Crowded, sub-standard housing (often lacking potable drinking water and basic sanitary facilities), malnutrition and the absence of access to medical care make them particularly subject to contagious diseases such as parasitic infections, hepatitis, tuberculosis and, more recently, AIDS. They are often underpaid or actually cheated of much of what they earn, especially when they are living illegally in a country and hence are denied basic legal rights. If apprehended by authorities, it is usually the “undocumented” migrant workers who are penalized rather than the employers and contractors who exploit them. Further, particularly during periods of economic downturn and rising unemployment, even documented migrant workers may be subject to deportation.

The International Labour Organization has for long been concerned with the problems of migrant workers. It first addressed them in its Migration for Employment Convention, 1949 (No. 97), and the related Recommendation No. 86, and revisited them in its Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention, 1975 (No. 143), and the related Recommendation No. 151. These Conventions, which have the force of treaties when ratified by countries, contain provisions aimed at eliminating abusive conditions and ensuring basic human rights and equal treatment for migrants. The recommendations provide non-binding guidelines to orient national policy and practice; Recommendation No. 86, for example, includes a model bilateral agreement that can be used by two countries as the basis for an operational agreement on the management of migrant labour.

In 1990, the United Nations adopted the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, which formulates basic human rights for migrant workers and their families, including: the right not to be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; the right to be treated no less favourably than national workers in respect to conditions of work and terms of employment; and the right to join unions and seek their assistance. This UN Convention will enter into force when it has been ratified by 20 nations; as of July 1995, it had been ratified by only five (Egypt, Colombia, Morocco, the Philippines and Seychelles) and it had been signed but not yet formally ratified by Chile and Mexico. It should be noted that neither the ILO nor the UN has any power to compel compliance with the Conventions other than collective political pressures, and must rely on the Member States to enforce them.

It has been observed that, at least in Asia, international dialogue on the matter of migrant workers has been hindered by its political sensitivity. Lim and Oishi (1996) note that countries exporting workers are fearful of losing their market share to others, especially since the recent global economic downturn has prompted more countries to enter the international market for migrant labour and to export their ‘‘cheap and docile’’ labour to a limited number of increasingly choosy host countries.

Piece-Workers

Piece-work is a compensation system that pays workers per unit of production accomplished. The unit of payment may be based on completion of the entire item or article or just one stage in its production. This system is generally applied in industries where the method of production consists of distinct, repetitive tasks whose performance can be credited to an individual worker. Thus, earnings are directly linked to the individual worker’s productivity (in some workplaces producing larger or more complicated items, such as automobiles, the workers are organized into teams which divide the per piece payment). Some employers share the rewards of greater productivity by supplementing the per piece payments with bonuses based on the profitability of the enterprise.

Piece-work is concentrated, by and large, in low-paying, light industries such as apparel and small assembly shops. It is also characteristic for sales people, independent contractors, repair personnel and others who are usually seen as different from shop workers.

The system can work well when employers are enlightened and concerned about workers’ health and welfare, and particularly where the workers are organized into a trade union in order to bargain collectively for rates of payment per unit, for appropriate and well-maintained tools and equipment, for a working environment where hazards are eliminated or controlled and personal protective equipment is provided when needed, and for pensions, health insurance and other such benefits. It is helped by the ready accessibility of managers or supervisors who are themselves skilled in the production process and can train or assist workers who may be having difficulty with it and who can help to maintain a high level of morale in the workplace by paying attention to workers’ concerns.

The piece-work system, however, readily lends itself to the exploitation of the workers, with adverse effects on their health and well-being, as in the following considerations:

- Piece-work is characteristic of the notorious sweatshops, unfortunately still common in the garment and electronic industries, where workers must toil at repetitive tasks, often for 12-hour days and 7-day weeks in sub-standard and hazardous workplaces.

- Even where the employer may manifest concern about potential occupational hazards—and this does not always occur—the pressure for productivity may leave little inclination for workers to devote what amounts to unpaid time to health and safety education. It may lead them to ignore or by-pass measures designed to control potential hazards, such as removing safety guards and shields. At the same time, employers have found that there may be a drop in the quality of the work, which dictates enhancement of product inspections to prevent defective merchandise from being passed along to the customers.

- The rate of pay may be so low that earning a living wage becomes difficult or nigh impossible.

- Piece-workers may be considered “temporary” workers and as such can be declared ineligible for benefits that may be mandatory for most workers.

- Less-skilled, slower workers may be denied training that would enable them to keep pace with those who can work faster, while employers may establish quotas based on what the best workers can produce and fire those unable to meet them. (In some workplaces, workers agree among themselves on production quotas that require the faster workers to slow down or stop working, thereby spreading the available work and the earnings more evenly among the work group.)

Contract Labour

Contract labour is a system in which a third party or organization contracts with employers to provide the services of workers when and where they are needed. They fall into three categories:

- Temporary workers are hired for a short period to fill in for employees who are absent because of illness or who are on leave, to augment the workforce when peaks in workload are not likely to be sustained, and when particular skills are needed only for a limited period.

- Leased workers are supplied on a more or less permanent basis to employers who, for a variety of reasons, do not wish to increase their workforces. These reasons include saving the effort and costs of personnel management and avoiding commitments such as rate of pay and the benefits won by the “regular” employees. In some instances, jobs have been eliminated in the course of a “downsizing” and the same people rehired as leased workers.

- Contract workers are groups of workers recruited by contractors and transported, sometimes for great distances and to other countries, to perform jobs that cannot be filled locally. These are usually low-paying, less desirable jobs involving hard physical labour or repetitive work. Some contractors recruit workers striving to improve their lots by emigrating to a new country and make them sign agreements committing them to work at the behest of the particular contractor until the often exorbitant transportation costs, fees and living expenses have been repaid.

One fundamental issue among the many possible problems with such arrangements, is whether the owner of the enterprise or the contractor supplying the workers is responsible for the safety, health and welfare of the workers. There is often “buck-passing”, in which each claims that the other is responsible for substandard working conditions (and, when the workers are migrants, living conditions) while the workers, who may be unfamiliar with the local language, laws and customs and too poor to obtain legal assistance, remain powerless to correct them. Contract workers are often exposed to physical and chemical hazards and are denied the education and training required to recognize and cope with them.

Informal Workers

The informal or “ undocumented” work sector includes workers who agree to work “off the books”—that is, without any formal registration or employer/employee arrangement. Payment may be in cash or in “in kind” goods or services and, since earnings are not reported to the authorities, they are not subject either to regulation or taxation for the worker and the employer. As a rule, there are no fringe benefits.

In many instances, informal work is done on an ad hoc, part-time basis, often while “moonlighting” during or after working hours on another job. It is also common among housekeepers and nannies who may be imported (sometimes illegally) from other countries where paid work is difficult to find. Many of these are required to “live in” and work long hours with very little time off. Since room and board may be considered part of their pay, their cash earnings may be very small. Finally, physical abuse and sexual harassment are not infrequent problems for these household workers (Anderson 1993).

The employer’s responsibility for the informal worker’s health and safety is only implicit, at best, and is often denied. Also, the worker is generally not eligible for workers’ compensation benefits in the event of a work-related accident or illness, and may be forced to take legal action when needed health services are not provided by the employer, a major undertaking for most of these individuals and not possible in all jurisdictions.

Slavery

Slavery is an arrangement in which one individual is regarded as an item of property, owned, exploited and dominated by another who can deny freedom of activity and movement, and who is obliged to provide only minimal food, shelter and clothing. Slaves may not marry and raise families without the owner’s permission, and may be sold or given away at will. Slaves may be required to perform any and all kinds of work without compensation and, short of the threat of impairing a valuable possession, with no concern for their health and safety.

Slavery has existed in every culture from the beginnings of human civilization as we know it down to the present. It was mentioned in the Sumerian legal codes recorded around 4,000 BC and in the Code of Hammurabi that was spelled out in ancient Babylon in the eighteenth century BC, and it exists today in parts of the world despite being prohibited by the UN’s 1945 Declaration of Human Rights and attacked and condemned by virtually every international organization including the UN Economic and Social Council, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the ILO (Pinney 1993). Slaves have been employed in every kind of economy and, in some agricultural and manufacturing societies, have been the mainstay of production. In the slave-owning societies in the Middle East, Africa and China, slaves were employed primarily for personal and domestic services.

Slaves have traditionally been members of a different racial, ethnic, political or religious group from their owners. They were usually captured in wars or raids but, ever since the time of ancient Egypt, it has been possible for impoverished workers to sell themselves, or their wives and children, into bondage in order to pay off debts (ILO 1993b).

Unemployment and Employment Opportunity

In every country and in every type of economy there are workers who are unemployed (defined as those who are able and willing to work and who are seeking a job). Periods of unemployment are a regular feature of some industries in which the labour force expands and contracts in accord with the seasons (e.g., agriculture, construction and the apparel industry) and in cyclical industries in which workers are laid off when business declines and are rehired when it improves. Also, a certain level of turnover is characteristic of the labour market as employees leave one job to seek a better one and as young people enter the workforce replacing those who are retiring. This has been labelled frictional unemployment.

Structural unemployment occurs when whole industries decline as a result of technological advances (e.g., mining and the manufacture of steel) or in response to gross changes in the local economy. An example of the latter is the moving of manufacturing plants from an area where wages have become high to less developed areas where cheaper labour is available.

Structural unemployment, during recent decades, has also resulted from the spate of mergers, takeovers and restructurings of large enterprises that have been a common phenomenon, particularly in the United States which has far fewer mandated safeguards for worker and community well-being than do other industrialized countries. These have led to “downsizing” and shrinkage of their workforces as duplicative plants and offices have been eliminated and many jobs declared unnecessary. This has been damaging not only to those who lost their jobs but also to those who remained and were left with a loss of job security and a fear of being declared redundant.

Structural unemployment is often intractable as many workers lack the skill and flexibility to qualify for other jobs at a comparable level that may be available locally, and they often lack the resources to migrate to other areas where such jobs may be available.

When sizeable layoffs occur, there is often a “domino” effect on the community. The loss of earnings has a dampening effect on the local economy, causing the closing of shops and service enterprises frequented by the unemployed and, thereby, increasing their number.

The economic and mental stress resulting from unemployment often has significant adverse effects on the health of the workers and their families. Loss of job and, particularly, threats of job loss, have been found to be the most potent work-related stressors and have been shown to have precipitated emotional illnesses (this is discussed elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia). To prevent such adverse effects, some employers offer retraining and assistance in finding new jobs, and many countries have laws that place specific economic and social requirements on employers to provide financial and social benefits to the affected employees.

The underemployed comprise workers whose productive capacities are not fully utilized. They include part-time workers who are seeking full-time jobs, and those with higher levels of skill who can find only relatively unskilled work. In addition to lower earnings, they suffer the adverse effects of the stress of dissatisfaction with the job.

Child Labour

In most families, as soon as they are old enough to contribute, children are expected to work. This may involve helping with housekeeping chores, running errands or caring for younger siblings—in general, helping with the traditional homemaking responsibilities. In farming families or those engaged in some form of home industry, children are usually expected to help with tasks suited to their size and capabilities. These activities are almost invariably part-time, and often seasonal. Except in families where the children may be abused or exploited, this work is defined by the size and “values” of the particular family; it is unpaid and it usually does not interfere with nurturing, education and training. This article does not address such work. Rather, it focuses on children under the age of 14 who work outside the family framework in one industry or another, usually in defiance of laws and regulations governing the employment of children.

Although only sparse data are available, the ILO Bureau of Statistics has estimated that “in the developing countries alone, there are at least 120 million children between the ages of 5 and 14 who are fully at work, and more than twice as many (or about 250 million) if those for whom work is a secondary activity are included” (ILO 1996).

Earlier figures are thought to be grossly understated, as demonstrated by the much higher numbers yielded by independent surveys carried out in several countries in 1993–1994. For example, in Ghana, India, Indonesia and Senegal, approximately 25% of all children were engaged in some form of economic activity. For one-third of these children, work was their principal activity.

Child labour is found everywhere, although it is much more prevalent in poor and developing areas. It disproportionately involves girls who are not only likely to work for longer hours but, like older women, are also required to perform homemaking and housekeeping tasks to a much greater extent than their male counterparts. Children in rural areas are, on average, twice as likely to be economically active; among migrant farmworker families, it is almost the rule that all of the children work alongside their parents. However, the proportion of urban children who work is increasing steadily, mainly in the informal sector of the economy. Most urban children work in domestic services, although many are employed in manufacturing. While public attention has been focused on a few export industries such as textiles, clothing, footwear and carpets, the great majority work in jobs geared towards domestic consumption. On the whole, however, child labour remains more common on plantations than in manufacturing.

Child slavery

Many child workers are slaves. That is, the employer exercises the right of either temporary or permanent ownership in which the children have become “commodities” that can be rented out or exchanged. Traditional in South Asia, the sub-Saharan strip of East Africa and, more recently, in several South American countries, it appears to be evolving all over the world. Despite the facts that it is illegal in most countries where it exists and that the international Conventions banning it have been widely ratified, the ILO estimated (accurate data are not available) that there are tens of millions of child slaves around the world (ILO 1995). Large numbers of child slaves are to be found in agriculture, domestic service, the sex industry, the carpet and textile industries, quarrying and brick-making.

According to the report of an ILO Committee of Experts (ILO 1990), more than 30 million children are thought to be in slavery or bondage in several countries. The report cited, among others, India, Ghana, Gaza, Pakistan, Philippines, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Brazil, Peru, Mauritania, South Africa and Thailand. More than 10 million of them are concentrated in India and Pakistan. Common sites of employment for enslaved children are small workshops and as forced labour on plantations. In the informal sector they can be found in carpet weaving, match factories, glass factories, brick making, fish cleaning, mines and quarries. Children are also used as enslaved domestic labourers, as slave-prostitutes and drug carriers.

Child slavery predominates mainly where there are social systems that are based on the exploitation of poverty. Families sell the children outright or bond them into slavery in order to pay off debts or simply provide the wherewithal to survive, or to supply the means to meet social or religious obligations. In many instances, the payment is considered an advance against the wages the child slaves are expected to earn during their indenture. Wars and the forced migrations of large populations which disrupt the normal family structure force many children and adolescents into slavery.

Causes of child labour

Poverty is the greatest single factor responsible for the movement of children into the workplace. The survival of the family as well as the children themselves often dictates it; this is particularly the case when poor families have many children. The necessity of having them work full-time makes it impossible for families to invest in the children’s education.

Even where tuition is free, many poor families are unable to meet the ancillary costs of education (e.g., books and other school supplies, clothing and footwear, transportation and so on). In some places, these costs for one child attending a primary school may represent as much as one-third of the cash income of a typical poor family. This leaves going to work as the only alternative. In some large families, the older children will work to provide the means for educating their younger siblings.

In some areas, it is not so much the cost but the lack of schools providing an acceptable quality of education. In some communities, schools may just be unavailable. In others, children drop out because the schools serving the poor are of such abysmal quality that attendance does not seem to be worth the cost and effort involved. Thus, while many children drop out of school because they have to work, many become so discouraged that they prefer to work. As a result, they may remain totally or functionally illiterate and unable to develop the skills required for their advancement in the world of work and in society.

Finally, many large urban centres have developed an indigenous population of street children who have been orphaned or separated from their families. These scratch out a precarious existence by doing odd jobs, begging, stealing, and participating in the traffic of illegal drugs.

The demand for child labour

In most instances, children are employed because their labour is less expensive and they are less troublesome than adult workers. In Ghana, for example, an ILO-supported study showed that three-fourths of children engaged in paid work were paid less than one-sixth of the statutory minimum wage (ILO 1995). In other areas, although the differentials between the wages of children and adults were much less impressive, they were large enough to represent a very significant burden to the employers, who were usually poor, small contractors who enjoyed a very slim profit margin.

In some instances, as in the hand-woven carpet and glass bracelet (bangles) industries in India, child workers are preferred to adults because of their smaller size or the perception that their “nimble fingers” make for greater manual dexterity. An ILO study demonstrated that adults were no less competent in performing these tasks and that the child workers were not irreplaceable (Levison et al. 1995).

Parents are a major source of demand for the work of children in their own families. Huge numbers of children are unpaid workers in family farms, shops and stores that depend on family labour for their economic viability. It is conventionally assumed that these children are much less likely to be exploited than those working outside the family, but there is ample evidence that this is not always the case.

Finally, in urban areas in developed countries where the labour market is very tight, adolescents may be the only workers available and willing to take the minimum wage, mostly part-time jobs in retail establishments such as fast-food shops, retail trade and messenger services. Recently, where even these have not been available in sufficient numbers, employers have been recruiting elderly retirees for these positions.

Working conditions

In many establishments employing child labour, working conditions range from bad to abysmal. Since many of these enterprises are poor and marginal to start with, and are often operating illegally, little or no attention is paid to amenities that would be required to retain all but slave labourers. Lack of elementary sanitation, air quality, potable water and food are often compounded by crowding, harsh discipline, obsolete equipment, poor quality tools and the absence of protective measures to control exposure to occupational hazards. Even where some protective equipment may be available, it is rarely sized to fit the smaller frames of children and is often poorly maintained.

Too many children work too many hours. Dawn to dusk is not an unusual working day, and the need for rest periods and holidays is generally ignored. In addition to chronic fatigue, which is a major cause of accidents, the most damaging effect of the long hours is the inability to benefit from education. This may occur even where the children work only part-time; studies have shown that working more than 20 hours per week can negatively affect education (ILO 1995). Functional illiteracy and lack of training, in turn, lead to greatly diminished opportunities for advancing to improved employment.

Girls are particularly at risk. Because they are often also responsible for household tasks, they work longer hours than boys, who usually engage only in economic activities. As a result, they generally have lower rates of school attendance and completion.

Children are emotionally immature and need a nurturing psychological and social environment that will socialize them into their cultural environment and enable them to take their places as adults in their particular society. For many labouring children, the work environment is oppressive; in essence, they do not have a childhood.

Prevention of Injuries to Children

Child labour is not restricted to developing countries. The following set of precautions is adapted from advice put forth by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The risks for work-related injuries and illnesses in children, as in workers of all ages, can be reduced through adherence to routine precautions such as: prescribed housekeeping practices; training and safe work procedures; use of proper shoes, gloves and protective clothing; and maintenance and use of equipment with safety features. In addition, workers under the age of 18 should not be required to lift objects weighing more than 15 pounds (approximately 7kg) more than once per minute, or ever to lift objects weighing more than 30 pounds (14kg); tasks involving continuous lifting should never last more than 2 hours. Children under the age of 18 should not participate in work requiring the routine use of respirators as a means of preventing the inhalation of hazardous substances.

Employers should be knowledgeable about and comply with child labour laws. School counsellors and physicians who sign permits allowing children to work should be familiar with child labour laws and ensure that the work they approve does not involve prohibited activities.

Most children who begin working under the age of 18 enter the workplace with minimal prior experience for a job. Advanced industrial countries are not exempt from these hazards. For example, during the summer of 1992 in the United States, more than half (54%) of persons aged 14 to 16 years treated in emergency departments for work injuries reported that they had received no training in prevention of the injury they had sustained, and that a supervisor was present at the time of injury in only approximately 20% of the cases. Differences in maturity and developmental level regarding learning styles, judgement and behaviour should be considered when providing training for youth in occupational safety and health.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996

Exposure to occupational hazards

In general, the risks that children face in the workplace are the same that adult workers encounter. However, their effects may be greater because of the kinds of tasks to which children are assigned and the biological differences between children and adults.

Children tend to be given more menial tasks, often without instruction and training in minimizing exposure to the hazards that may be encountered, and without proper supervision. They may be assigned to cleaning-up duties, often using solvents or strong alkalis, or they may be required to clean up hazardous wastes that have accumulated in the workplace without awareness of potential toxicity.

Because of their smaller size, children are more likely to be given tasks that require working in odd, confined places or long periods of stooping or kneeling. Often, they are required to handle objects that even adults would consider too bulky or too heavy.

Because of their continuing growth and development, children differ biologically from adults. These differences have not been quantified, but it is reasonable to assume that the more rapid cell division involved in the growth process may make them more vulnerable to many toxic agents. Exposure earlier in life to toxic agents with long latency periods may result in the onset of disabling chronic occupational diseases such as asbestosis and cancer in young adulthood rather than at older ages, and there is evidence that childhood exposure to toxic chemicals may alter the response to future toxic exposures (Weisburger et al. 1966).

Table 1 summarizes information on some of the hazardous agents to which working children may be exposed, according to the sources of exposure and the types of health consequences. It should be noted that these consequences may be aggravated when the exposed children are undernourished, anaemic or suffer from chronic diseases. Finally, the lack of primary medical care, much less the services of health professionals with some sophistication in occupational health, means that these health consequences are not likely to be recognized promptly or treated effectively.

Table 1. Some occupations and industries, and their associated hazards, where children are employed.

|

Occupation/industry |

Hazards |

|

Abattoirs and meat rendering |

Injuries from cuts, burns, falls, dangerous equipment; exposure to infectious disease; heat stress |

|

Agriculture |

Unsafe machinery; hazardous substances; accidents; chemical poisoning; arduous work; dangerous animals, insects and reptiles |

|

Alcohol production and/or sale |

Intoxication, addiction; environment may be prejudicial to morals; risk of violence |

|

Carpet-weaving |

Dust inhalation, poor lighting, poor posture (squatting); respiratory and musculoskeletal diseases; eye strain; chemical poisoning |

|

Cement |

Harmful chemicals, exposure to harmful dust; arduous work; respiratory and musculoskeletal disease |

|

Construction and/or demolition |

Exposure to heat, cold, dust; falling objects; sharp objects; accidents; musculoskeletal diseases |

|

Cranes/hoists/lifting machinery Tar, asphalt, bitumen |

Accidents; falling objects; musculoskeletal diseases; risk of injury to others Exposure to heat, burns; chemical poisoning; respiratory diseases |

|

Crystal and/or glass manufacture |

Molten glass; extreme heat; poor ventilation; cuts from broken glass; carrying hot glass; burns; respiratory disease; heat stress; toxic dust |

|

Domestic service |

Long hours; physical, emotional, sexual abuse; malnutrition; insufficient rest; isolation |

|

Electricity |

Dangerous work with high voltage; risk of falling; high level of responsibility for safety of others |

|

Entertainment (night clubs, bars, casinos, circuses, gambling halls) |

Long, late hours; sexual abuse; exploitation; prejudicial to morals |

|

Explosives (manufacture and handling) |

Risk of explosion, fire, burns, mortal danger |

|

Hospitals and work with risk of infection |

Infectious diseases; responsibility for well-being of others |

|

Lead/zinc metallurgy |

Cumulative poisoning; neurological damage |

|

Machinery in motion (operation, cleaning, repairs, etc.) |

Danger from moving engine parts; accidents; cuts, burns, exposure to heat and noise; noise stress; eye and ear injuries |

|

Maritime work (trimmers and stokers, stevedores) |

Accidents; heat, burns; falls from heights; heavy lifting, arduous work, musculoskeletal diseases; respiratory diseases |

|

Mining, quarries, underground work |

Exposure to dusts, gases, fumes, dirty conditions; respiratory and musculoskeletal diseases; accidents; falling objects; arduous work; heavy loads |

|

Rubber |

Heat, burns, chemical poisoning |

|

Street trades |

Exposure to drugs, violence, criminal activities; heavy loads; musculoskeletal diseases; venereal diseases; accidents |

|

Tanneries |

Chemical poisoning; sharp instruments; respiratory diseases |

|

Transportation, operating vehicles |

Accidents; danger to self and passengers |

|

Underwater (e.g., pearl diving) |

Decompression illness; dangerous fish; death or injury |

|

Welding and smelting of metals, metalworking |

Exposure to extreme heat; flying sparks and hot metal objects; accidents; eye injuries; heat stress |

Source: Sinclair and Trah 1991.

Social and economic consequences of child labour

Child labour is largely generated by poverty, as noted above, and child labour tends to perpetuate poverty. When child labour precludes or seriously handicaps education, lifetime earnings are reduced and upward social mobility is retarded. Work that hampers the physical, mental and social development ultimately taxes the health and welfare resources of the community and perpetuates poverty by degrading the stock of human capital needed for the economic and social development of the society. Since the societal costs of child labour are visited primarily on the population groups that already are poor and less privileged, access to democracy and social justice is eroded and social unrest is fomented.

Future trends

Although much is being done to eliminate child labour, it is clearly not enough nor is it effective enough. What is needed first is more and better information about the extent, dynamics and effects of child labour. The next step is to increase, amplify and improve educational and training opportunities for children from pre-school through universities and technical institutes, and then to provide the means for children of the poor to take advantage of them (e.g., adequate housing, nutrition and preventive health care).

Well-drafted legislation and regulations, reinforced by such international efforts as the ILO Conventions, need constantly to be revised and strengthened in the light of current developments in child labour, while the effectiveness of their enforcement should be enhanced.

The ultimate weapon may be the nurturing of greater awareness and abhorrence of child labour among the general public, which we are beginning to see in several industrialized countries (motivated in part by adult unemployment and the price competition that drives producers of consumer goods to migrate to areas where labour may be cheaper). The resultant publicity is leading to damage to the image of organizations marketing products produced by child labour, protests by their stockholders and, most important, refusal to purchase these products even though they may cost a bit less.

Conclusions

There are many forms of employment in which workers are vulnerable to impoverishment, exploitation and abuse, and where their safety, health and well-being are at great risk. Despite attempts at legislation and regulation, and notwithstanding their condemnation in international agreements, Conventions, and resolutions, such conditions are likely to persist as long as people are poor, ill-housed, malnourished and oppressed, and are denied the information, education and training and the curative and preventive health services required to enable them to extricate themselves from the social quicksand in which they exist. Wealthy people and nations often respond magnanimously to such natural disasters as storms, floods, fires, volcanic eruptions and earthquakes but, important as they are, the benefits of such help are short-lived. What is needed is a long-term application of human effort fortified by the needed resources that will overcome the political, racial and religious barriers that would thwart its thrust.

Finally, while it is entirely appropriate and healthy for children to work as part of normal development and family life, child labour as described in this article is a scourge that not only damages the health and well-being of the child workers but, in the long run, also impairs the social and economic security of communities and nations. It must be attacked with vigour and persistence until it is eradicated.

Pregnancy and US Work Recommendations

Changes in family life over recent decades have had dramatic effects on the relationship between work and pregnancy. These include the following:

- Women, particularly those of childbearing age, continue to enter the labour force in considerable numbers.

- A tendency has developed on the part of many of these women to defer starting their families until they are older, by which time they have often achieved positions of responsibility and become important members of the productive apparatus.

- At the same time, there is an increasing number of teenage pregnancies, many of which are high-risk pregnancies.

- Reflecting increasing rates of separation, of divorce and of choices of alternative lifestyles, as well as an increase in the number of families in which both parents must work, financial pressures are forcing many women to continue working for as long as possible during pregnancy.

The impact of pregnancy-related absences and lost or impaired productivity, as well as concern over the health and well-being of both the mothers and their infants, have led employers to become more proactive in dealing with the problem of pregnancy and work. Where employers pay all or part of health insurance premiums, the prospect of avoiding the sometimes staggering costs of complicated pregnancies and neonatal problems is a potent incentive. Certain responses are dictated by laws and government regulations, for example, guarding against potential occupational and environmental hazards and providing maternity leave and other benefits. Others are voluntary: prenatal education and care programmers, modified work arrangements such as flex-time and other work schedule arrangements, dependant care and other benefits.

Management of pregnancy

Of primary importance to the pregnant woman—and to her employer—whether or not she continues working during her pregnancy, is access to a professional health management programme designed to identify and avert or minimize risks to the mother and her foetus, thus enabling her to remain on the job without concern. At each of the scheduled prenatal visits, the physician or midwife should evaluate medical information (childbearing and other medical history, current complaints, physical examinations and laboratory tests) and information about her job and work environment, and develop appropriate recommendations.

It is important that health professionals not rely on the simple job descriptions pertaining to their patients’ work, as these are often inaccurate and misleading. The job information should include details concerning physical activity, chemical and other exposures and emotional stress, most of which can be provided by the woman herself. In some instances, however, input from a supervisor, often relayed by the safety department or the employee health service (where there is one), may be needed to provide a more complete picture of hazardous or trying work activities and the possibility of controlling their potential for harm. This can also serve as a check on patients who inadvertently or deliberately mislead their physicians; they may exaggerate the risks or, if they feel it is important to continue working, may understate them.

Recommendations for Work

Recommendations regarding work during pregnancy fall into three categories:

The woman may continue to work without changes in her activities or the environment. This is applicable in most instances. After extensive deliberation, the Task Force on the Disability of pregnancy comprising obstetrical health professionals, occupational physicians and nurses, and women’s representatives assembled by ACOG (the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) and NIOSH (the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) concluded that “the normal woman with an uncomplicated pregnancy who is in a job that presents no greater hazards than those encountered in normal daily life in the community, may continue to work without interruption until the onset of labor and may resume working several weeks after an uncomplicated delivery” (Isenman and Warshaw, 1977).

The woman may continue to work, but only with certain modifications in the work environment or her work activities. These modifications would be either “desirable” or “essential” (in the latter case, she should stop work if they cannot be made).

The woman should not work. It is the physician’s or midwife’s judgement that any work would probably be detrimental to her health or to that of the developing foetus.