Diagnosis

The diagnosis of neurotoxic disease is not easy. The errors are usually of two types: either it is not recognized that a neurotoxic agent is the cause of neurological symptoms, or neurological (and especially neurobehavioural) symptoms are erroneously diagnosed as resulting from an occupational, neurotoxic exposure. Both of these errors can be hazardous since an early diagnosis is important in the case of neurotoxic disease, and the best treatment is avoiding further exposure for the individual case and the surveillance of the condition of other workers in order to prevent their exposure to the same danger. On the other hand, sometimes undue alarm can develop in the workplace if a worker claims to have serious symptoms and suspects a chemical exposure as the cause but in fact, either the worker is mistaken or the hazard is not actually present for others. There is practical reason for correct diagnostic procedures, as well, since in many countries, the diagnosis and treatment of occupational diseases and the loss of working capacity and invalidity caused by those diseases are covered by insurance; thus the financial compensation may be disputed, if the diagnostic criteria are not solid. An example of a decision tree for neurological assessment is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Decision tree for neurotoxic disease

I. Relevant exposure level, length and type

II. Appropriate symptoms insidiously increasing central (CNS) or peripheral (PNS) nervous system symptoms

III. Signs and additional tests CNS dysfunction: neurology, psychology tests PNS dysfunction: quantitative sensory test, nerve conduction studies

IV. Other diseases excluded in differential diagnosis

Exposure and Symptoms

Acute neurotoxic syndromes occur mainly in accidental situations, when workers are exposed short-term to very high levels of a chemical or to a mixture of chemicals generally through inhalation. The usual symptoms are vertigo, malaise and possible loss of consciousness as a result of depression of the central nervous system. When the subject is removed from the exposure, the symptoms disappear rather quickly, unless the exposure has been so intense that it is life-threatening, in which case coma and death may follow. In these situations recognition of the hazard must occur at the workplace, and the victim should be taken out into the fresh air immediately.

In general, neurotoxic symptoms arise after short-term or long-term exposures, and often at relatively low-level occupational exposure levels. In these cases acute symptoms may have occurred at work, but the presence of acute symptoms is not necessary for diagnosis of chronic toxic encephalopathy or toxic neuropathy to be made. However, patients do often report headache, light-headedness or mucosal irritation at the end of a working day, but these symptoms initially disappear during the night, weekend or vacation. A useful checklist can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Consistent neuro-functional effects of worksite exposures to some leading neurotoxic substances

|

Mixed organic solvents |

Carbon disulphide |

Styrene |

Organophos- |

Lead |

Mercury |

|

|

Acquisition |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

Affect |

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

Categorization |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coding |

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

Colour vision |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

Concept shifting |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Distractibility |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

Intelligence |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Memory |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Motor coordination |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

Motor speed |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

Near visual contrast sensitivity |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Odour perception threshold |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Odour identification |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

Personality |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

Spatial relations |

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

Vibrotactile threshold |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

Vigilance |

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

Visual field |

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

Vocabulary |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

Source: Adapted from Anger 1990.

Assuming that the patient has been exposed to neurotoxic chemicals, the diagnosis of neurotoxic disease starts with symptoms. In 1985, a joint working group of the World Health Organization and the Nordic Council of Ministers discussed the matter of chronic organic solvent intoxication and found a set of core symptoms, which are found in most cases (WHO/Nordic Council 1985). The core symptoms are fatigability, memory loss, difficulties in concentration, and loss of initiative. These symptoms usually start after a basic change in personality, which develops gradually and affects energy, intellect, emotion and motivation. Among other symptoms of chronic toxic encephalopathy are depression, dysphoria, emotional lability, headache, irritability, sleep disturbances and dizziness (vertigo). If there is also involvement of the peripheral nervous system, numbness and possibly muscular weakness develop. Such chronic symptoms last for at least a year after the exposure itself has ended.

Clinical Examination and Testing

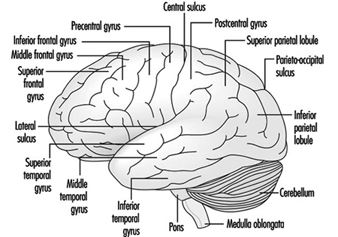

The clinical examination should include a neurological examination, where attention should be paid to impairment of higher nervous functions, such as memory, cognition, reasoning and emotion; to impaired cerebellar functions, like tremor, gait, station and coordination; and to peripheral nervous functions, especially vibration sensitivity and other tests of sensation. Psychological tests can provide objective measures of higher nervous system functions, including psychomotor, short-term memory, verbal and non-verbal reasoning and perceptual functions. In individual diagnosis the tests should include some tests that give a clue as to the person’s premorbid intellectual level. History of school performance and previous job performance as well as possible psychological tests administered previously, for example in connection with military service, can help in the evaluation of the person’s normal level of performance.

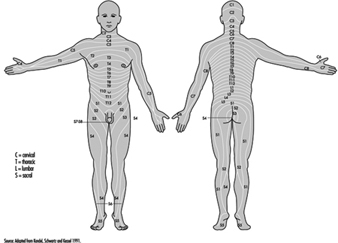

The peripheral nervous system can be studied with quantitative tests of sensory modalities, vibration and thermosensibility. Nerve conduction velocity studies and electromyography can often reveal neuropathy at an early stage. In these tests special emphasis should be on sensory nerve functions. The amplitude of the sensory action potential (SNAP) decreases more often than the sensory conduction velocity in axonal neuropathies, and most toxic neuropathies are axonal in character. Neuroradiological studies such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) usually do not reveal anything pertinent to chronic toxic encephalopathy, but they may be useful in the differential diagnosis.

In the differential diagnosis other neurological and psychiatric diseases should be considered. Dementia of other aetiology should be ruled out, as well as depression and stress symptoms of various causes. Psychiatric consultation may be necessary. Alcohol abuse is a relevant confounding factor; excessive use of alcohol causes symptoms similar to those of solvent exposure, and on the other hand there are papers indicating that solvent exposure may induce alcohol abuse. Other causes for neuropathy also have to be ruled out, especially entrapment neuropathies, diabetes and kidney disease; also alcohol causes neuropathy. The combination of encephalopathy and neuropathy is more likely of toxic origin than either of these alone.

In the final decision the exposure should be evaluated again. Was there relevant exposure, considering the level, length and quality of exposure? Solvents are more likely to induce psycho-organic syndrome or toxic encephalopathy; hexacarbons, however, usually first cause neuropathy. Lead and some other metals cause neuropathy, although CNS involvement can be detected later on.

Measuring Neurotoxic Deficits

Neuro-functional Test Batteries

Sub-clinical neurologic signs and symptoms have long been noted among active workers exposed to neurotoxins; however, it is only since the mid-1960s that research efforts have focused on the development of sensitive test batteries capable of detecting subtle, mild changes that are present in the early stages of intoxication, in perceptual, psychomotor, cognitive, sensory and motor functions, and affect.

The first neurobehavioural test battery for use in worksite studies was developed by Helena Hänninen, a pioneer in the field of neurobehavioural deficits associated with toxic exposure (Hänninen Test Battery) (Hänninen and Lindstrom 1979). Since then, there have been worldwide efforts to develop, refine and, in some cases, computerize neurobehavioural test batteries. Anger (1990) describes five worksite neurobehavioural test batteries from Australia, Sweden, Britain, Finland and the United States, as well as two neurotoxic screening batteries from the United States, that have been used in studies of neurotoxin-exposed workers. In addition, the computerized Neurobehavioral Evaluation System (NES) and the Swedish Performance Evaluation System (SPES) have been extensively used around the world. There are also test batteries designed to assess sensory functions, including measures of vision, vibrotactile perception threshold, smell, hearing and sway (Mergler 1995). Studies of various neurotoxic agents using one or another of these batteries have greatly contributed to our knowledge of early neurotoxic impairment; however, cross-study comparisons have been difficult since different tests are used and tests with similar names may be administered using a different protocol.

In an attempt to standardize information from studies on neurotoxic substances, the notion of a “core” battery was put forward by a working committee of the World Health Organization (WHO) (Johnson 1987). Based on knowledge at the time of the meeting (1985), a series of tests were selected to make up the Neurobehavioral Core Test Battery (NCTB), a relatively inexpensive, hand-administered battery, which has been successfully used in many countries (Anger et al. 1993). The tests that make up this battery were chosen to cover specific nervous system domains, which had been previously shown to be sensitive to neurotoxic damage. A more recent core battery, which comprises both hand-administered and computerized tests, has been proposed by a workgroup of the United States Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (Hutchison et al. 1992). Both batteries are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of "core" batteries for assessment of early neurotoxic effects

|

Neurobehavioural Core Test Battery (NCTB)+ |

Test order |

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Adult Environmental Neurobehavioural Test Battery (AENTB)+ |

||

|

Functional domain |

Test |

Functional domain |

Test |

|

|

Motor steadiness |

Aiming (Pursuit Aiming II) |

1 |

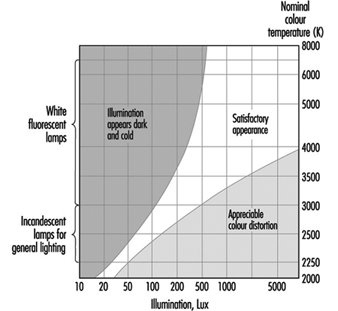

Vision |

Visual acuity, near contrast sensitivity |

|

Attention/response speed |

Simple Reaction Time |

2 |

Colour vision (Lanthony D-15 desaturated test) |

|

|

Perceptual motor speed |

Digit Symbol (WAIS-R) |

3 |

Somatosensory |

Vibrotactile perception threshold |

|

Manual dexterity |

Santa Ana (Helsinki Version) |

4 |

Motor strength |

Dynamometer (including fatigue assessment) |

|

Visual perception/memory |

Benton Visual Retention |

5 |

Motor coordination |

Santa Ana |

|

Auditory memory |

Digit Span (WAIS-R, WMS) |

6 |

Higher intellectual function |

Raven Progressive Matrices (Revised) |

|

Affect |

POMS (Profile of Mood States) |

7 |

Motor coordination |

Fingertapping Test (one hand)1 |

|

8 |

Sustained attention (cognitive), speed (motor) |

Simple Reaction Time (SRT) (extended)1 |

||

|

9 |

Cognitive coding |

Symbol-digit with delayed recall1 |

||

|

10 |

Learning and memory |

Serial Digit Learning1 |

||

|

11 |

Index of educational level |

Vocabulary1 |

||

|

12 |

Mood |

Mood Scale1 |

||

1 Available in computerized version; WAIS = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; WMS = Wechsler Memory Scale.

The authors of both core batteries stress that, although the batteries are useful to standardize results, they by no means provide complete assessment of nervous system functions. Additional tests should be used depending upon the type of exposure; for example, a test battery to assess nervous system dysfunction among manganese-exposed workers would include more tests of motor functions, particularly those that require rapid alternating movements, while one for methylmercury-exposed workers would include visual field testing. The choice of tests for any particular workplace should be made on the basis of current knowledge on the action of the particular toxin or toxins to which the persons are exposed.

More sophisticated test batteries, administered and interpreted by trained psychologists, are an important part of the clinical assessment for neurotoxic poisoning (Hart 1988). It includes tests of intellectual ability, attention, concentration and orientation, memory, visuo-perceptive, constructive and motor skills, language, conceptual and executive functions, and psychological well-being, as well as an assessment of possible malingering. The profile of the patient’s performance is examined in the light of past and present medical and psychological history, as well as exposure history. The final diagnosis is based on a constellation of deficits interpreted in relation to the type of exposure.

Measures of Emotional State and Personality

Studies of the effects of neurotoxic substances usually include measures of affective or personality disturbance, in the form of symptoms questionnaires, mood scales or personality indices. The NCTB, described above, includes the Profile of Mood States (POMS), a quantitative measure of mood. Using 65 qualifying adjectives of mood states over the past 8 days, the degrees of tension, depression, hostility, vigour, fatigue and confusion are derived. Most comparative workplace studies of neurotoxic exposure indicate differences between exposed and non-exposed. A recent study of styrene-exposed workers shows dose-response relations between post-shift urinary mandelic acid level, a biological indicator of styrene, and scale scores of tension, hostility, fatigue and confusion (Sassine et al. 1996).

Lengthier and more sophisticated tests of affect and personality, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Index (MMPI), which reflect both emotional states and personality traits, have been used primarily for clinical evaluation, but also in workplace studies. The MMPI likewise provides an assessment of symptom exaggeration and inconsistent responses. In a study of microelectronics workers with a history of exposure to neurotoxic substances, results from the MMPI indicated clinically significant levels of depression, anxiety, somatic concerns and disturbances of thinking (Bowler et al. 1991).

Electrophysiological Measures

Electrical activity generated by the transmission of information along nerve fibres and from one cell to another, can be recorded and used in the determination of what is happening in the nervous system of persons with toxic exposures. Interference with neuronal activity can slow down transmission or modify the electrical pattern. Electrophysiological recordings require precise instruments and are most frequently carried out in a laboratory or hospital setting. There have, however, been efforts to develop more portable equipment for use in workplace studies.

Electrophysiological measures record a global response of a large number of nerve fibres and/or fibres, and a fair amount of damage must exist before it can be adequately recorded. Thus, for most neurotoxic substances, symptoms, as well as sensory, motor and cognitive changes, usually can be detected in groups of exposed workers before electrophysiological differences are observed. For clinical examination of persons with suspected neurotoxic disorders, electrophysiological methods provide information concerning the type and extent of nervous system damage. A review of electrophysiological techniques used in the detection of early neurotoxicity in humans is provided by Seppalaïnen (1988).

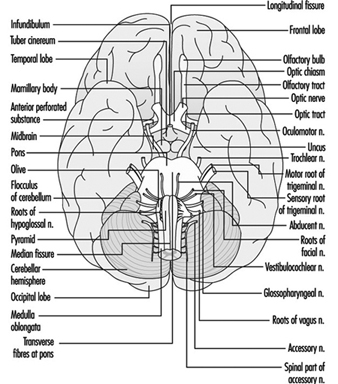

The nerve conduction velocity of sensory nerves (going towards the brain) and motor nerves (going away from the brain) are measured by electroneurography (ENG). By stimulating at different anatomical positions and recording at another, the conduction velocity can be calculated. This technique can provide information about the large myelinated fibres; slowing of conduction velocity occurs when demyelination is present. Reduced conduction velocities have frequently been observed among lead-exposed workers, in the absence of neurological symptoms (Maizlish and Feo 1994). Slow conduction velocities of peripheral nerves have also been associated with other neurotoxins, such as mercury, hexacarbons, carbon disulphide, styrene, methyl-n-butyl ketone, methyl ethyl ketone, and certain solvent mixtures. The trigeminal nerve (a facial nerve) is affected by trichloroethylene exposure. However, if the toxic substance acts primarily on thinly myelinated or unmyelinated fibres, conduction velocities usually remain normal.

Electromyography (EMG) is used for measuring the electrical activity in muscles. Electromyographic abnormalities have been observed among workers with exposure to such substances as n-hexane, carbon disulphide, methyl-n-butyl ketone, mercury and certain pesticides. These changes are often accompanied by changes in ENG and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy.

Changes in brainwaves are evidenced by electroencephalography (EEG). In patients with organic solvent poisoning, local and diffuse slow wave abnormalities have been observed. Some studies report evidence of dose-related EEG alterations among active workers, with exposure to organic solvent mixtures, styrene and carbon disulphide. Organochlorine pesticides can cause epileptic seizures, with EEG abnormalities. EEG changes have been reported with long-term exposure to organophosphorus and zinc phosphide pesticides.

Evoked potentials (EP) provides another means of examining nervous system activity in response to a sensory stimulus. Recording electrodes are placed on the specific area of the brain that responds to the particular stimuli, and the latency and amplitude of the event-related slow potential are recorded. Increased latency and/or reduced peak amplitudes have been observed in response to visual, auditory and somatosensory stimuli for a wide range of neurotoxic substances.

Electrocardiography (ECG or EKG) records changes in the electrical conduction of the heart. Although it is not often used in studies of neurotoxic substances, changes in ECG waves have been observed among persons with exposure to trichloroethylene. Electro-oculographic (EOG) recordings of eye movements have shown alterations among workers with exposure to lead.

Brain Imaging Techniques

In recent years, different techniques have been developed for brain imaging. Computed tomographic (CT) images reveal the anatomy of the brain and spinal cord. They have been used to study cerebral atrophy among solvent-exposed workers and patients; however, the results are not consistent. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examines the nervous system using a powerful magnetic field. It is particularly useful clinically to rule out an alternative diagnosis, such as brain tumours. Positron Emission Tomography (PET), which yields images of biochemical processes, has been successfully used to study changes in the brain induced by manganese intoxication. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) provides information about brain metabolism and may prove to be an important tool in understanding how neurotoxins act on the brain. These techniques are all very costly, and not readily available in most hospitals or laboratories throughout the world.

Clinical Syndromes Associated with Neurotoxicity

Neurotoxicant syndromes, brought about by substances which adversely affect nervous tissue, constitute one of the ten leading occupational disorders in the United States. Neurotoxicant effects constitute the basis for establishing exposure limit criteria for approximately 40% of agents considered hazardous by the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

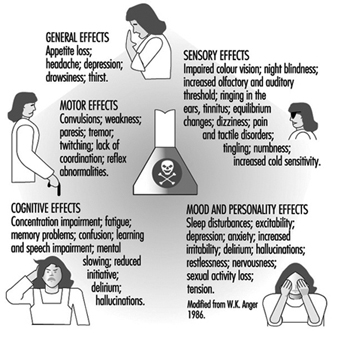

A neurotoxin is any substance capable of interfering with the normal function of nervous tissue, causing irreversible cellular damage and/or resulting in cellular death. Depending on its particular properties, a given neurotoxin will attack selected sites or specific cellular elements of the nervous system. Those compounds, which are non-polar, have greater lipid solubility, and thus have greater access to nervous tissue than highly polar and less lipid-soluble chemicals. The type and size of cells and the various neurotransmitter systems affected in different regions of the brain, innate protective detoxifying mechanisms, as well as the integrity of cellular membranes and intracellular organelles all influence neurotoxicant responses.

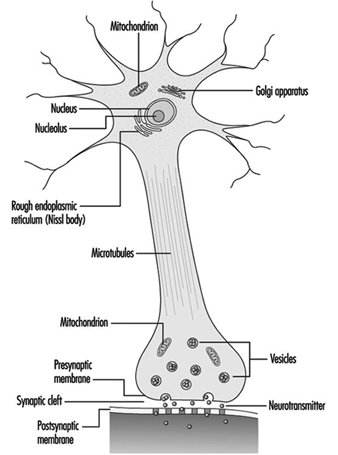

Neurons (the functional cell unit of the nervous system) have a high metabolic rate and are at greatest risk for neurotoxicant damage, followed by oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, microglia and cells of the capillary endothelium. Changes in cellular membrane structure impair excitability and impede impulse transmission. Toxicant effects alter protein form, fluid content and ionic exchange capability of membranes, leading to swelling of neurons, astrocytes and damage to the delicate cells lining blood capillaries. Disruption of neurotransmitter mechanisms block access to post-synaptic receptors, produce false neurotransmitter effects, and alter the synthesis, storage, release, re-uptake or enzymatic inactivation of natural neurotransmitters. Thus, clinical manifestations of neurotoxicity are determined by a number of different factors: the physical characteristics of the neurotoxicant substance, the dose of exposure to it, the vulnerability of the cellular target, the organism’s ability to metabolize and excrete the toxin, and by the reparative abilities of the structures and mechanisms affected. Table 1 lists various chemical exposures and their neurotoxic syndromes.

Table 1. Chemical exposures and associated neurotoxic syndromes

|

Neurotoxin |

Sources of exposure |

Clinical diagnosis |

Locus of pathology1 |

|

Metals |

|||

|

Arsenic |

Pesticides; pigments; antifouling paint; electroplating industry; seafood; smelters; semiconductors |

Acute: encephalopathy Chronic: peripheral neuropathy |

Unknown (a) Axon (c) |

|

Lead |

Solder; lead shot; illicit whiskey; insecticides; auto body shop; storage battery manufacturing; foundries, smelters; lead-based paint; lead pipes |

Acute: encephalopathy Chronic: encephalopathy and peripheral neuropathy |

Blood vessels (a) Axon (c) |

|

Manganese |

Iron, steel industry; welding operations; metal-finishing operations; fertilizers; manufacturers of fireworks, matches; manufacturers of dry cell batteries |

Acute: encephalopathy Chronic: parkinsonism |

Unknown (a) Basal ganglia neurons (c) |

|

Mercury |

Scientific instruments; electrical equipment; amalgams; electroplating industry; photography; felt making |

Acute: headache, nausea, onset of tremor Chronic: ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, encephalopathy |

Unknown (a) Axon (c) Unknown (c) |

|

Tin |

Canning industry; solder; electronic components; polyvinyl plastics; fungicides |

Acute: memory defects, seizures, disorientation Chronic: encephalomyelopathy |

Neurons of the limbic system (a & c) Myelin (c) |

|

Solvents |

|||

|

Carbon disulphide |

Manufacturers of viscose rayon; preservatives; textiles; rubber cement; varnishes; electroplating industry |

Acute: encephalopathy Chronic: peripheral neuropathy, parkinsonism |

Unknown (a) Axon (c) Unknown |

|

n-hexane, methyl butyl ketone |

Paints; lacquers; varnishes; metal-cleaning compounds; quick-drying inks; paint removers; glues, adhesives |

Acute: narcosis Chronic: peripheral neuropathy, unknown (a) Axon (c), |

|

|

Perchloroethylene |

Paint removers; degreasers; extraction agents; dry cleaning industry; textile industry |

Acute: narcosis Chronic: peripheral neuropathy, encephalopathy |

Unknown (a) Axon (c) Unknown |

|

Toluene |

Rubber solvents; cleaning agents; glues; manufacturers of benzene; gasoline, aviation fuels; paints, paint thinners; lacquers |

Acute: narcosis Chronic: ataxia, encephalopathy |

Unknown (a) Cerebellum (c) Unknown |

|

Trichloroethylene |

Degreasers; painting industry; varnishes; spot removers; process of decaffeination; dry cleaning industry; rubber solvents |

Acute: narcosis Chronic: encephalopathy, cranial neuropathy |

Unknown (a) Unknown (c) Axon (c) |

|

Insecticides |

|||

|

Organophosphates |

Agricultural industry manufacturing and application |

Acute: cholinergic poisoning Chronic: ataxia, paralysis, peripheral neuropathy |

Acetylcholinesterase (a) Long tracts of spinal cord (c) Axon (c) |

|

Carbamates |

Agricultural industry manufacturing and application flea powders |

Acute: cholinergic poisoning Chronic: tremor, peripheral neuropathy |

Acetylcholinesterase (a) Dopaminergic system (c) |

1 (a), acute; (c), chronic.

Source: Modified from Feldman 1990, with permission of the publisher.

Establishing a diagnosis of a neurotoxicant syndrome and differentiating it from neurologic diseases of non-neurotoxicant aetiology requires an understanding of the pathogenesis of the neurological symptoms and observed signs and symptoms; an awareness that particular substances are capable of affecting nervous tissue; documentation of exposure; evidence of presence of neurotoxin and/or metabolites in tissues of an affected individual; and careful delineation of a time relationship between exposure and the appearance of symptoms with subsequent decrease in symptoms after exposure is ended.

Proof that a particular substance has reached a toxicant dose level is usually lacking after symptoms appear. Unless environmental monitoring is ongoing, a high index of suspicion is necessary to recognize cases of neurotoxicologic injury. Identifying symptoms referable to the central and/or the peripheral nervous systems can help the clinician focus on certain substances, which have a greater predilection for one part or another of the nervous system, as possible culprits. Convulsions, weakness, tremor/twitching, anorexia (weight loss), equilibrium disturbance, central nervous system depression, narcosis (a state of stupor or unconsciousness), visual disturbance, sleep disturbance, ataxia (inability to coordinate voluntary muscle movements), fatigue and tactile disorders are commonly reported symptoms following exposure to certain chemicals. Constellations of symptoms form syndromes associated with neurotoxicant exposure.

Behavioural Syndromes

Disorders with predominantly behavioural features ranging from acute psychosis, depression and chronic apathy have been described in some workers. It is essential to differentiate memory impairment associated with other neurological diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, arteriosclerosis or presence of a brain tumour, from the cognitive deficits associated with toxicant exposure to organic solvents, metals or insecticides. Transient disturbances of awareness or epileptic seizures with or without associated motor involvement must be identified as a primary diagnosis separate from similarly appearing disturbances of consciousness related to neurotoxicant effects. Subjective and behavioural toxicant syndromes such as headache, vertigo, fatigue and personality change manifest as mild encephalopathy with inebriation, and may indicate the presence of exposure to carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, lead, zinc, nitrates or mixed organic solvents. Standardized neuropsychological testing is necessary to document elements of cognitive impairment in patients suspected of toxicant encephalopathy, and these must be differentiated from those dementing syndromes caused by other pathologies. Specific tests used in the diagnostic batteries of tests must include a broad sampling of cognitive function tests which will generate predictions about the patient’s functioning and daily life, as well as tests which have been demonstrated previously to be sensitive to the effects of known neurotoxins. These standardized batteries must include tests which have been validated on patients with specific types of brain damage and structural deficits, to clearly separate these conditions from neurotoxic effects. In addition, tests must include internal control measures to detect the influence of motivation, hypochondriasis, depression and learning difficulties, and must contain language that takes into account cultural as well as educational background effects.

A continuum exists from mild to severe central nervous system impairment experienced by patients exposed to toxicant substances:

- Organic affective syndrome (Type I Effect), in which mild mood disorders predominate as the patient’s chief complaint, with features most consistent with those of organic affective disorders of the depressive type. This syndrome seems to be reversible following cessation of exposure to the offending agent.

- Mild chronic toxicant encephalopathy, in which, in addition to mood disturbances, central nervous system impairment is more prominent. Patients have evidence of memory and psychomotor function disturbance which can be confirmed by neuropsychological testing. In addition, features of visual spatial impairment and abstract concept formation may be seen. Activities of daily living and work performance are impaired.

- Sustained personality or mood change (Type IIA Effect) or impairment in intellectual function (Type II) may be seen. In mild chronic toxicant encephalopathy, the course is insidious. Features may persist after the cessation of exposure and disappear gradually, while in some individuals, persistent functional impairment may be observed. If exposure continues, the encephalopathy may progress to a more severe stage.

- In severe chronic toxicant encephalopathy (Type III Effect) dementia with global deterioration of memory and other cognitive problems are noted. The clinical effects of toxicant encephalopathy are not specific to a given agent. Chronic encephalopathy associated with toluene, lead and arsenic is not different from that of other toxicant aetiologies. The presence of other associated findings, however (visual disturbances with methyl alcohol), may help differentiate syndromes according to particular chemical aetiologies.

Workers exposed to solvents for long periods of time may exhibit disturbances of central nervous system function which are permanent. Since an excess of subjective symptoms, including headache, fatigue, impaired memory, loss of appetite and diffuse chest pains, have been reported, it is often difficult to confirm this effect in any individual case. An epidemiological study comparing house painters exposed to solvents with unexposed industrial workers showed, for example, that painters had significantly lower mean scores on psychological tests measuring intellectual capacity and psychomotor coordination than referent subjects. The painters also had significantly lower performances than expected on memory and reaction time tests. Differences between workers exposed for several years to jet fuel and unexposed workers, in tests demanding close attention and high sensory motor speed, were apparent as well. Impairments in psychological performance and personality changes have also been reported among car painters. These included visual and verbal memory, reduction of emotional reactivity, and poor performance on verbal intelligence tests.

Most recently, a controversial neurotoxicant syndrome, multiple chemical sensitivity, has been described. Such patients develop a variety of features involving multiple organ systems when they are exposed to even low levels of various chemicals found in the workplace and the environment. Mood disturbances are characterized by depression, fatigue, irritability and poor concentration. These symptoms reoccur on exposure to predictable stimuli, by elicitation by chemicals of diverse structural and toxicological classes, and at levels much lower than those causing adverse responses in the general population. Many of the symptoms of multiple chemical sensitivity are shared by individuals who show only a mild form of mood disturbance, headache, fatigue, irritability and forgetfulness when they are in a building with poor ventilation and with off-gassing of volatile substances from synthetic building materials and carpets. The symptoms disappear when they leave these environments.

Disturbances of consciousness, seizures and coma

When the brain is deprived of oxygen—for example, in the presence of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane or agents which block tissue respiration such as hydrocyanic acid, or those which cause massive impregnation of the nerve such as certain organic solvents—disturbances of consciousness may result. Loss of consciousness may be preceded by seizures in workers with exposure to anticholinesterase substances such as organophosphate insecticides. Seizures may also occur with lead encephalopathy associated with brain swelling. Manifestations of acute toxicity following organophosphate poisoning have autonomic nervous system manifestations which precede the occurrence of dizziness, headache, blurred vision, myosis, chest pain, increased bronchial secretions, and seizures. These parasympathetic effects are explained by the inhibitory action of these toxicant substances on cholinesterase activity.

Movement disorders

Slowness of movement, increased muscle tone, and postural abnormalities have been observed in workers exposed to manganese, carbon monoxide, carbon disulphide and the toxicity of a meperidine by-product, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). At times, the individuals may appear to have Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism secondary to toxicant exposure has features of other nervous disorders such as chorea and athetosis. The typical “pill-rolling” tremor is not seen in these instances, and usually the cases do not respond well to the drug levodopa. Dyskinesia (impairment of the power of voluntary motion) can be a common symptom of bromomethane poisoning. Spasmodic movements of the fingers, face, peribuccal muscles and the neck, as well as extremity spasms, may be seen. Tremor is common following mercury poisoning. More obvious tremor associated with ataxia (lack of coordination of muscular action) is noted in individuals following toluene inhalation.

Opsoclonus is an abnormal eye movement which is jerky in all directions. This is often seen in brain-stem encephalitis, but may also be a feature following chlordecone exposure. The abnormality consists of irregular bursts of abrupt, involuntary, rapid, simultaneous jerking of both eyes in a conjugate manner, possibly multidirectional in severely affected individuals.

Headache

Common complaints of head pain following exposure to various metal fumes such as zinc and other solvent vapours may result from vasodilation (widening of the blood vessels), as well as cerebral oedema (swelling). The experiencing of pain is common to these conditions, as well as carbon monoxide, hypoxia (low oxygen), or carbon dioxide conditions. “Sick building syndrome” is thought to cause headaches because of excess carbon dioxide present in a poorly ventilated area.

Peripheral neuropathy

Peripheral nerve fibres serving motor functions begin in motor neurons in the ventral horn of the spinal cord. The motor axons extend peripherally to the muscles they innervate. A sensory nerve fibre has its nerve cell body in the dorsal root ganglion or in the dorsal grey matter of the spinal cord. Having received information from the periphery detected at distal receptors, nerve impulses are conducted centrally to the nerve cell bodies where they connect with spinal cord pathways transmitting information to the brain stem and cerebral hemispheres. Some sensory fibres have immediate connections with motor fibres within the spinal cord, providing a basis for reflex activity and quick motor responses to noxious sensations. These sensory-motor relationships exist in all parts of the body; the cranial nerves are the peripheral nerve equivalents arising in brain stem, rather than spinal cord, neurons. Sensory and motor nerve fibres travel together in bundles and are referred to as the peripheral nerves.

Toxicant effects of peripheral nerve fibres may be divided into those which primarily affect axons (axonopathies), those which are involved in distal sensory-motor loss, and those which primarily affect myelin sheath and Schwann cells. Axonopathies are evident in early stages in the lower extremities where the axons are the longest and farthest from the nerve cell body. Random demyelination occurs in segments between nodes of Ranvier. If sufficient axonal damage occurs, secondary demyelination follows; as long as axons are preserved, regeneration of Schwann cells and remyelination can occur. A pattern seen commonly in toxicant neuropathies is distal axonopathy with secondary segmental demyelination. The loss of myelin reduces the speed of conducting nerve impulses. Thus, gradual onset of intermittent tingling and numbness progressing to lack of sensation and unpleasant sensations, muscle weakness, and atrophy results from damage to the motor and sensory fibres. Reduced or absent tendon reflexes and anatomically consistent patterns of sensory loss, involving the lower extremities more than upper, are features of peripheral neuropathy.

Motor weaknesses may be noted in distal extremities and progress to unsteady gait and inability to grasp objects. The distal portions of the extremities are involved to a greater extent, but severe cases may produce proximal muscle weakness or atrophy as well. Extensor muscle groups are involved before the flexors. Symptoms may sometimes progress for a few weeks even after removal from exposure. Deterioration of nerve function may persist for several weeks after removal from exposure.

Depending on the type and severity of neuropathy, an electrophysiological examination of the peripheral nerves is useful to document impaired function. Slowing of conduction velocity, reduced amplitudes of sensory or motor action potentials, or prolonged latencies can be observed. Slowing of motor or sensory conduction velocities is generally associated with demyelination of nerve fibres. Preservation of normal conduction velocity values in the presence of muscle atrophy suggests axonal neuropathy. Exceptions occur when there is progressive loss of motor and sensory nerve fibres in axonal neuropathy which affects the maximal conduction speed as a result of the dropping out of the larger diameter faster conducting nerve fibres. Regenerating fibres occur in early stages of recovery in axonopathies, in which conduction is slowed, especially in the distal segments. The electrophysiological study of patients with toxicant neuropathies should include measurements of motor and sensory conduction velocity in the upper and lower extremities. Special attention should be given to the primarily sensory conducting characteristics of the sural nerve in the leg. This is of great value when the sural nerve is then used for biopsy, providing anatomical correlation between the histology of teased nerve fibres and the conduction characteristics. A differential electrophysiological study of the conducting capabilities of proximal segments versus distal segments of a nerve is useful in identifying a distal toxicant axonopathy, or to localize a neuropathic block of conduction, probably due to demyelination.

Understanding the pathophysiology of a suspected neurotoxicant polyneuropathy has great value. For example, in patients with neuropathy caused by n-hexane and methylbutyl ketone, motor nerve conduction velocities are reduced, but in some cases, the values may fall within the normal range if only the fastest firing fibres are stimulated and used as the measured outcome. Since neurotoxicant hexacarbon solvents cause axonal degeneration, secondary changes arise in myelin and explain overall reduction in conduction velocity despite the value within the normal range produced by the preserved conducting fibres.

Electrophysiological techniques include special tests other than the direct conduction velocity, amplitude and latency studies. Somatosensory evoked potentials, auditory evoked potentials, and visual evoked potentials are ways of studying the characteristics of the sensory conducting systems, as well as specific cranial nerves. Afferent-efferent circuitry can be tested by using blink reflex tests involving the 5th cranial nerve to 7th cranial innervated muscle responses; H-reflexes involve segmental motor reflex pathways. Vibration stimulation selects out larger fibres from smaller fibre involvements. Well-controlled electronic techniques are available for measuring the threshold needed to elicit a response, and then to determine the speed of travel of that response, as well as the amplitude of the muscle contraction, or the amplitude and pattern of an evoked sensory action potential. All physiological results must be evaluated in light of the clinical picture and with an understanding of the underlying pathophysiological process.

Conclusion

The differentiation of a neurotoxicant syndrome from a primary neurological disease poses a formidable challenge to physicians in the occupational setting. Obtaining a good history, maintaining a high degree of suspicion and adequate follow-up of an individual, as well as groups of individuals, is necessary and rewarding. Early recognition of illness related to toxicant agents in their environment or to a particular occupational exposure is critical, since proper diagnosis can lead to early removal of an individual from the hazards of ongoing exposure to a toxicant substance, preventing possible irreversible neurological damage. Furthermore, recognition of the earliest affected cases in a particular setting may result in changes that will protect others who have not yet become affected.

Manifestations of Acute and Early Chronic Poisoning

Current knowledge of the short- and long-term manifestations of exposure to neurotoxic substances comes from experimental animal studies and human chamber studies, epidemiological studies of active and retired and/or diseased workers, clinical studies and reports, as well as large-scale disasters, such as those that occurred in Bhopal, following a leak of methyl isocyanate, and in Minamata, from methyl mercury poisoning.

Exposure to neurotoxic substances can produce immediate effects (acute) and/or long-term effects (chronic). In both cases, the effects can be reversible and disappear over time following reduction or cessation of exposure, or result in permanent, irreversible damage. The severity of acute and chronic nervous system impairment depends on exposure dose, which includes both the quantity and duration of exposure. Like alcohol and recreational drugs, many neurotoxic substances may initially be excitatory, producing a sensation of well-being or euphoria and/or speeding up motor functions; as the dose increases in quantity or in time, these same neurotoxins will depress the nervous system. Indeed, narcosis (a state of stupor or insensibility) is induced by a large number of neurotoxic substances, which are mind-altering and depress the central nervous system.

Acute Poisoning

Acute effects reflect the immediate response to the chemical substance. The severity of the symptoms and resulting disorders depends on the quantity that reaches the nervous system. With mild exposures, acute effects are mild and transient, disappearing when exposure ceases. Headache, tiredness, light-headedness, difficulty concentrating, feelings of drunkenness, euphoria, irritability, dizziness and slowed reflexes are the types of symptoms experienced during exposure to neurotoxic chemicals. Although these symptoms are reversible, when exposure is repeated day after day, the symptoms recur as well. Moreover, since the neurotoxic substance is not immediately eliminated from the body, symptoms can persist following work. Reported symptoms at a particular workstation are a good reflection of chemical interference with the nervous system and should be considered a warning signal for potential over-exposure; preventive measures to reduce exposure levels should be initiated.

If exposure is very high, as can occur with spills, leaks, explosions and other accidents, symptoms and signs of intoxication are debilitating (severe headaches, mental confusion, nausea, dizziness, incoordination, blurred vision, loss of consciousness); if exposure is high enough, effects can be long-lasting, possibly resulting in coma and death.

Acute pesticide-related disorders are a common occurrence among agricultural workers in food-producing countries, where large amounts of toxic substances are used as insecticides, fungicides, nematicides, and herbicides. Organophosphates, carbamates, organochlorines, pyrethrum, pyrethrin, paraquat and diquat are among the major categories of pesticides; however, there are thousands of pesticide formulations, containing hundreds of different active ingredients. Some pesticides, such as maneb, contain manganese, while others are dissolved in organic solvents. In addition to the symptoms mentioned above, acute organophosphate and carbamate poisoning may be accompanied by salivation, incontinence, convulsions, muscle twitching, diarrhoea, visual disturbances, as well as respiratory difficulties and a rapid heart rate; these result from an excess of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which occurs when these substances attack a chemical called cholinesterase. Blood cholinesterase decreases proportionally to the degree of acute organophosphate or carbamate intoxication.

With some substances, such as organophosphorus pesticides and carbon monoxide, high-level acute exposures can produce delayed deterioration of certain parts of the nervous system. For the former, numbness and tingling, weakness and disequilibrium can occur a few weeks after exposure, while for the latter, delayed neurologic deterioration can take place, with symptoms of mental confusion, ataxia, motor incoordination and paresis. Repeated acute episodes of high levels of carbon monoxide have been associated with later-life Parkinsonism. It is possible that high exposures to certain neurotoxic chemicals may be associated with an increased risk for neurodegenerative disorders later on in life.

Chronic Poisoning

Recognition of the hazards of neurotoxic chemicals has led many countries to reduce the permissible exposure levels. However, for most chemicals, the level at which no adverse effect will occur over long-term exposure is still unknown. Repeated exposure to low to medium levels of neurotoxic substances throughout many months or years can alter nervous system functions in an insidious and progressive manner. Continued interference with molecular and cellular processes causes neurophysiological and psychological functions to undergo slow alterations, which in the early stages may go unseen since there are large reserves in the nervous system circuitry and damage can, in the first stages, be compensated through new learning.

Thus, initial nervous system injury is not necessarily accompanied by functional disorders and may be reversible. However, as the damage progresses, symptoms and signs, often non-specific in nature, become apparent, and individuals may seek medical attention. Finally, impairment may become so severe that a clear clinical syndrome, generally irreversible, is manifest.

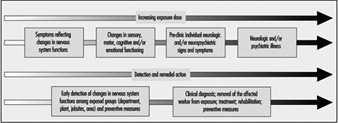

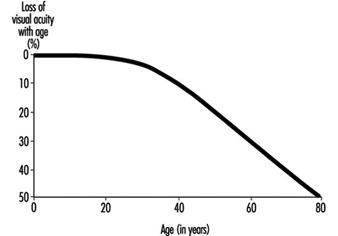

Figure 1 schematizes the health deterioration continuum associated with exposure to neurotoxic substances. Progression of neurotoxic dysfunction is dependent on both the duration and concentration of exposure (dose), and may be influenced by other workplace factors, individual health status and susceptibility as well as lifestyle, particularly drinking and exposure to neurotoxic substances used in hobbies, such as glues applied in furniture assembly or plastic model building, paints and paint removers.

Figure 1. Health deterioration on a continuum with increasing dosage

Different strategies are adopted for identification of neurotoxin-related illness among individual workers and for the surveillance of early nervous system deterioration among active workers. Clinical diagnosis relies on a constellation of signs and symptoms, coupled to the medical and exposure history for an individual; aetiologies other than exposure must be systematically ruled out. For the surveillance of early dysfunction among active workers, the group portrait of dysfunction is important. Most often, the pattern of dysfunction observed for the group will be similar to the pattern of impairment clinically observed in the disease. It is somewhat like summing early, mild alterations to produce a picture of what is happening to the nervous system. The pattern or profile of the overall early response provides an indication of the specificity and the type of action of the particular neurotoxic substance or mixture. In workplaces with potential exposure to neurotoxic substances, health surveillance of groups of workers may prove particularly useful for prevention and workplace action in order to avoid the development of more severe illness (see Figure 2). Workplace studies carried out throughout the world, with active workers exposed to specific neurotoxic substances or to mixtures of various chemicals, have provided valuable information on early manifestations of nervous system dysfunction in groups of exposed workers.

Figure 2. Preventing neurotoxicity at work.

Early symptoms of chronic poisoning

Altered mood states are most often the first symptoms of the initial changes in nervous system functioning. Irritability, euphoria, sudden mood changes, excessive tiredness, feelings of hostility, anxiousness, depression and tension are among the mood states most often associated with neurotoxic exposures. Other symptoms include memory problems, concentration difficulties, headaches, blurred vision, feelings of drunkenness, dizziness, slowness, tingling sensation in hands or feet, loss of libido and so on. Although in the early stages these symptoms are usually not sufficiently severe to interfere with work, they do reflect diminished well-being and affect one’s capacity to fully enjoy family and social relations. Often, because of the non-specific nature of these symptoms, workers, employers and occupational health professionals tend to ignore them and look for causes other than workplace exposure. Indeed, such symptoms may contribute to or aggravate an already difficult personal situation.

In workplaces where neurotoxic substances are used, workers, employers and occupational health and safety personnel should be particularly aware of the symptomatology of early intoxication, indicative of nervous system vulnerability to exposure. Symptom questionnaires have been developed for worksite studies and surveillance of workplaces where neurotoxic substances are used. Table 1 contains an example of such a questionnaire.

Table 1. Chronic symptoms checklist

Symptoms experienced in the past month

1. Have you tired more easily than expected for the type of activity you do?

2. Have you felt light-headed or dizzy?

3. Have you had difficulty concentrating?

4. Have you been confused or disoriented?

5. Have you had trouble remembering things?

6. Have your relatives noticed that you have trouble remembering things?

7. Have you had to make notes to remember things?

8. Have you found it hard to understand the meaning of newspapers?

9. Have you felt irritable?

10. Have you felt depressed?

11. Have you had heart palpitations even when you are not exerting yourself?

12. Have you had a seizure?

13. Have you been sleeping more often than is usual for you?

14. Have you had difficulty falling asleep?

15. Have you been bothered by incoordination or loss of balance?

16. Have you had any loss of muscle strength in your legs or feet?

17. Have you had any loss of muscle strength in your arms or hands?

18. Have you had difficulty moving your fingers or grasping things?

19. Have you had hand numbness and tingling in your fingers lasting for more than a day?

20. Have you had hand numbness and tinging in your toes lasting more than a day?

21. Have you had headaches at least once a week?

22. Have you had difficulty driving home from work because you felt dizzy or tired?

23. Have you felt “high” from the chemicals used at work?

24. Have you had a lower tolerance for alcohol (takes less to get drunk)?

Source: Taken from Johnson 1987.

Early motor, sensory and cognitive changes in chronicpoisoning

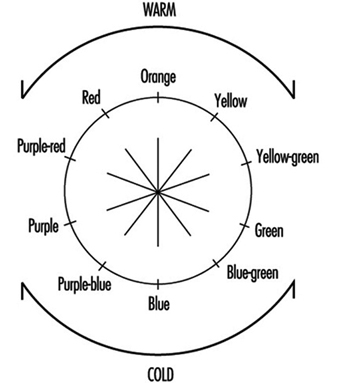

With increasing exposure, changes can be observed in motor, sensory and cognitive functions in workers exposed to neurotoxic substances, who do not present clinical evidence of abnormality. Since the nervous system is complex, and certain areas are vulnerable to specific chemicals, while others are sensitive to the action of a large number of toxic agents, a wide range of nervous system functions may be affected by a single toxic agent or a mixture of neurotoxins. Reaction time, hand-eye coordination, short-term memory, visual and auditory memory, attention and vigilance, manual dexterity, vocabulary, switching attention, grip strength, motor speed, hand steadiness, mood, colour vision, vibrotactile perception, hearing and smell are among the many functions that have been shown to be altered by different neurotoxic substances.

Important information on the type of early deficits that result from exposure has been provided by comparing performance between exposed and non-exposed workers and with respect to the degree of exposure. Anger (1990) provides an excellent review of worksite neurobehavioural research up to 1989. Table 2 adapted from this article, provides an example of the type of neuro-functional deficits that have been consistently observed in groups of active workers exposed to some of the most common neurotoxic substances.

Table 2. Consistent neuro-functional effects of worksite exposures to some leading neurotoxic substances

|

Mixed organic solvents |

Carbon disulphide |

Styrene |

Organophos- |

Lead |

Mercury |

|

|

Acquisition |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

Affect |

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

Categorization |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coding |

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

Colour vision |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

Concept shifting |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Distractibility |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

Intelligence |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Memory |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Motor coordination |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

Motor speed |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

Near visual contrast sensitivity |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Odour perception threshold |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Odour identification |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

Personality |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

Spatial relations |

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

Vibrotactile threshold |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

Vigilance |

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

Visual field |

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

Vocabulary |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

Source: Adapted from Anger 1990.

Although at this stage in the continuum from well-being to disease, loss is not in the clinically abnormal range, there can be health-related consequences associated with such changes. For example, decreased vigilance and reduced reflexes may put workers in greater danger of accidents. Smell is used to identify leaks and mask saturation (cartridge breakthrough), and acute or chronic loss of smell renders one less apt to identify a potentially hazardous situation. Mood changes may interfere with inter-personal relations at work, socially and in the home. These initial stages of nervous system deterioration, which can be observed by examining groups of exposed workers and comparing them to non-exposed workers or with respect to their degree of exposure, reflect diminished well-being and may be predictive of risk of more serious neurological problems in the future.

Mental health in chronic poisoning

Neuropsychiatric disorders have long been attributed to exposure to neurotoxic substances. Clinical descriptions range from affective disorders, including anxiety and depression, to manifestations of psychotic behaviour and hallucinations. Acute high-level exposure to many heavy metals, organic solvents and pesticides can produce delirium. “Manganese madness” has been described in persons with long-term exposure to manganese, and the well-known “mad hatter” syndrome results from mercury intoxication. Type 2a Toxic Encephalopathy, characterized by sustained change in personality involving fatigue, emotional lability, impulse control and general mood and motivation, has been associated with organic solvent exposure. There is growing evidence from clinical and population studies that personality disorders persist over time, long after exposure ceases, although other types of impairment may improve.

On the continuum from well-being to disease, mood changes, irritability and excessive fatigue are often the very first indications of over-exposure to neurotoxic substances. Although neuropsychiatric symptoms are routinely surveyed in worksite studies, these are rarely presented as a mental health problem with potential consequences on mental and social well-being. For example, changes in mental health status affect one’s behaviour, contributing to difficult inter-personal relationships and disagreements in the home; these in turn can aggravate one’s mental state. In workplaces with employee aid programmes, designed to help employees with personal problems, ignorance of the potential mental health effects of exposure to neurotoxic substances can lead to treatment dealing with the effects rather than the cause. It is interesting to note that among the many reported outbreaks of “mass hysteria” or psychogenic illness, industries with exposure to neurotoxic substances are over-represented. It is possible that these substances, which, for the large part, went unmeasured, contributed to the reported symptoms.

Mental health manifestations of neurotoxin exposure can be similar to those that are caused by psychosocial stressors associated with poor work organization, as well as psychological reactions to accidents, very stressful occurrences and severe intoxications, called post-traumatic stress disorder (as discussed elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia). A good understanding of the relation between mental health problems and working conditions is important to initiating adequate preventive and curative actions.

General considerations in assessing early neurotoxicdysfunction

When evaluating early nervous system dysfunction among active workers, a number of factors must be taken into account. Firstly, many of the neuropsychological and neurophysiological functions that are examined diminish with age; some are influenced by culture or educational level. These factors must be taken into account when considering the relation between exposure and nervous system alterations. This can be done by comparing groups with similar socio-demographic status or by using statistical methods of adjustment. There are, however, certain pitfalls that should be avoided. For example, older workers may have longer work histories, and it has been suggested that some neurotoxic substances may accelerate ageing. Job segregation may confine poorly educated workers, women and minorities in jobs with higher exposures. Secondly, alcohol consumption, smoking and drugs, which all contain neurotoxic substances, may also affect symptoms and performance. A good understanding of the workplace is important in unravelling the different factors that contribute to nervous system dysfunction and the implementation of preventive measures.

Chemical Neurotoxic Agents

Definition of Neurotoxicity

Neurotoxicity refers to the capability of inducing adverse effects in the central nervous system, peripheral nerves or sensory organs. A chemical is considered to be neurotoxic if it is capable of inducing a consistent pattern of neural dysfunction or change in the chemistry or structure of the nervous system.

Neurotoxicity is generally manifested as a continuum of symptoms and effects, which depend on the nature of the chemical, the dose, the duration of exposure and the traits of the exposed individual. The severity of the observed effects, as well as the evidence for neurotoxicity, increases through levels 1 to 6, shown in Table 1. Short-term or low-dose exposure to a neurotoxic chemical may result in subjective symptoms such as headache and dizziness, but the effect usually is reversible. With increasing dose, neurological changes may show up, and eventually irreversible morphological changes are generated. The degree of abnormality needed for implying neurotoxicity of a chemical agent is a controversial issue. According to the definition, a consistent pattern of neural dysfunction or change in the chemistry or structure of the nervous system is considered if there is well-documented evidence for persistent effects on level 3, 4, 5 or 6 in Table 1. These levels reflect the weight of evidence provided by different signs of neurotoxicity. Neurotoxic substances include naturally occurring elements such as lead, mercury and manganese; biological compounds such as tetrodotoxin (from the puffer fish, a Japanese delicacy) and domoic acid (from contaminated mussels); and synthetic compounds including many pesticides, industrial solvents and monomers.

Table 1. Grouping neurotoxic effects to reflect their relative strength for establishing neurotoxicity

|

Level |

Grouping |

Explanation/Examples |

|

6 |

Morphological changes |

Morphological changes include cell death and axonopathy as well as subcellular morphological changes. |

|

5 |

Neurological changes |

Neurological change embraces abnormal findings in neurological examinations on single individuals. |

|

4 |

Physiological/behavioural changes |

Physiological/behavioural changes comprise experimental findings on groups of animals or humans such as changes in evoked potentials and EEG, or changes in psychological and behavioural tests. |

|

3 |

Biochemical changes |

Biochemical changes cover changes in relevant biochemical parameters (e.g., transmitter level, GFA-protein content (glial fibrillary acidic protein) or enzyme activities). |

|

21 |

Irreversible, subjective symptoms |

Subjective symptoms. No evidence of abnormality on neurological, psychological or other medical examination. |

|

11 |

Reversible, subjective symptoms |

Subjective symptoms. No evidence of abnormality on neurological, psychological, or other medical examination. |

1 Humans only

Source: Modified from Simonsen et al. 1994.

In the United States between 50,000 and 100,000 chemicals are in commerce, and 1,000 to 1,600 new chemicals are submitted for evaluation each year. More than 750 chemicals and several classes or groups of chemical compounds are suspected to be neurotoxic (O’Donoghue 1985), but the majority of chemicals have never been tested for neurotoxic properties. Most of the known neurotoxic chemicals available today have been identified by case-reports or through accidents.

Although neurotoxic chemicals often are produced to fulfil specific uses, exposure may arise from several sources—use in private homes, in agriculture and in industries, or from polluted drinking water and so on. Fixed a priori preconceptions about which neurotoxic compounds are expected to be found in which occupations should therefore be viewed with caution, and the following citations should be looked upon as possible examples including a few of the most common neurotoxic chemicals (Arlien-Søborg 1992; O’Donoghue 1985; Spencer and Schaumburg 1980; WHO 1978).

Symptoms of Neurotoxicity

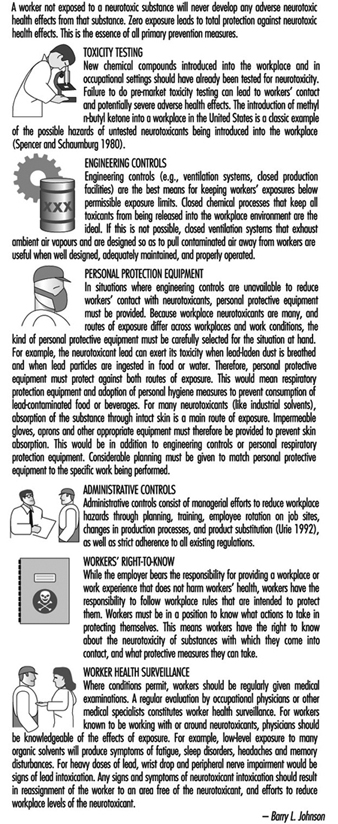

The nervous system generally reacts rather stereotypically to exposure to neurotoxic substances Figure 1. Some typical syndromes are indicated below.

Figure 1. Neurological and behavioural effects of exposure to neurotoxic chemicals.

Polyneuropathy

This is caused by impairment of motor and sensory nerve function leading to weakness of the muscles, with paresis usually most pronounced peripherally in the upper and lower extremities (hands and feet). Prior or simultaneous paraesthesia (tingling or numbness in the fingers and toes) may occur. This may lead to difficulties in walking or in the fine coordination of hands and fingers. Heavy metals, solvents and pesticides, among other chemicals, may result in such disability, even if the toxic mechanism of these compounds may be totally different.

Encephalopathy

This is caused by a diffuse impairment of the brain, and may result in fatigue; impairment of learning, memory and ability to concentrate; anxiety, depression, increased irritability and emotional instability. Such symptoms may indicate early diffuse degenerative brain disorder as well as occupational chronic toxic encephalopathy. Often increased frequency of headaches, dizziness, changes in sleep pattern and reduced sexual activity may also be present from the early stages of the disease. Such symptoms may develop following long-term, low-level exposure to several different chemicals such as solvents, heavy metals or hydrogen sulphide, and are also seen in several dementing disorders not related to work. In some cases more specific neurological symptoms can be seen (e.g., Parkinsonism with tremor, rigidity of the muscles and slowing of movements, or cerebellar symptoms such as tremor and reduced coordination of hand movements and gait). Such clinical pictures can be seen following exposure to some specific chemicals such as manganese, or MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) in the former condition, and toluene or mercury in the latter.

Gases

A wide variety of chemicals with totally different chemical structures are gases at normal temperature and have been proven neurotoxic Table 3. Some of them are extremely toxic even in very small doses, and have even been used as war gases (phosgene and cyanide); others require high doses over longer periods to give symptoms (e.g., carbon dioxide). Some are used for general anaesthesia (e.g., nitrous oxide); others are widely used in industry and in agents used for disinfection (e.g., formaldehyde). The former may induce irreversible changes in the nervous system after repeated low-level exposure, the latter apparently produce only acute symptoms. Exposure in small rooms with poor ventilation is particularly hazardous. Some of the gases are odourless, which makes them particularly dangerous (e.g., carbon monoxide). As shown in Table 2, some gases are important constituents in industrial production, while others are the result of incomplete or complete combustion (e.g., CO and CO2 respectively). This is seen in mining, steel works, power stations and so on, but may also be seen in private homes with insufficient ventilation. Essential for treatment is to stop further exposure and provide fresh air or oxygen, and in severe cases artificial ventilation.

Table 2. Gases associated with neurotoxic effects

|

Chemical |

Examples of source of exposure |

Selected industries at risk |

Effects1 |

|

Carbon dioxide (CO2 ) |

Welding; fermentation; manufacture, storage and use of dry ice |

Metal industry; mining; breweries |

M: Dilate vessels A: Headache; dyspnoea; tremor; loss of consciousness C: Hardly any |

|

Carbon monoxide (CO) |

Car repair; welding; metal melting; drivers; firemen |

Metal industry; mining; transportation; power station |

M: Deprivation of oxygen A: Headache; drowsiness; loss of consciousness |

|

Hydrogen sulphide (H2S) |

Fumigating of green house; manure; fishermen; fish unloading; sewerage handling |

Agriculture; fishing; sewer work |

M: Blocking oxidative metabolism A: Loss of consciousness C: Encephalopathy |

|

Cyanide (HCN) |

Electro-welding; galvanic surface treatment with nickel; copper and silver; fumigation of ships, houses foods and soil in green houses |

Metal industry; chemical industry; nursery; mining; gasworks |

M: Blocking of respiratory enzymes A: Dyspnoea; falling blood pressure; convulsions; loss of consciousness; death C: Encephalopathy; ataxia; neuropathy (e.g., aftereating cavasava) Occupational impairment uncertain |

|

Nitrous oxide (N2O) |

General anaesthesia during operation; light narcosis at dental care and delivery |

Hospitals (anaesthesia); dentists; midwife |

M: Acute change in nerve cell membrane; degeneration of nerve cells after long-term exposure A: Light-headedness; drowsiness; loss of consciousness C: Numbness of fingers and toes; reduced coordination; encephalopathy |

1 M: mechanism; A: acute effects; C: chronic effects.

Neuropathy: dysfunction of motor- and sensory peripheral nerve fibres.

Encephalopathy: brain dysfunction due to generalized impairment of the brain.

Ataxia: impaired motor coordination.

Metals

As a rule the toxicity of metals increases with increasing atomic weight, lead and mercury being particularly toxic. Metals are usually found in nature at low concentrations, but in certain industries they are used in great amounts (see Table 3) and may give rise to occupational risk for the workers. Moreover, considerable amounts of metals are found in waste water and may give rise to environmental risk for the residents close to the plants but also at greater distances. Often the metals (or, for example, organic mercury compounds) are taken up into the food chain and will accumulate in fish, birds and animals, representing a risk for consumers. The toxicity and the way in which the metals are handled by the organism may depend on the chemical structure. Pure metals may be taken up by inhalation or skin contact of vapour (mercury) and/or small particles (lead), or orally (lead). Inorganic mercury compounds (e.g., HgCl2) are mainly taken up by mouth, while organic metal compounds (e.g., tetraethyl lead) mainly are taken up by inhalation or by skin contact. The body burden may to a certain degree be reflected in the concentration of metal in the blood or urine. This is the basis for biological monitoring. In treatment it must be recalled that especially lead is released very slowly from deposits in the body. The amount of lead in bones will normally be reduced by only 50% over 10 years. This release may be speeded up by the use of chelating agents: BAL (dimercapto-1-propanol), Ca-EDTA or penicillamine.

Table 3. Metals and their inorganic compounds associated with neurotoxicity

|

Chemical |

Examples of source of exposure |

Selected industries at risk |

Effects1 |

|

Lead |

Melting; soldering; grinding; repair; glazing; plasticizer |

Metal work; mining; accumulator plants; car repair; shipyards; glass workers; ceramics; pottery; plastic |

M: Impairment of oxidative metabolism of nerve cells and glia A: Abdominal pain; headache; encephalopathy; seizures C: Encephalopathy; polyneuropathy, including drop hand |

|

Mercury Elemental |

Electrolysis; electrical instruments (gyroscope; manometer; thermometer; battery; electric bulb; tubes, etc.); amalgam filling |

Chloralkali plants; mining; electronics; dentistry; polymer production; paper and pulp industry |

M: Impairment at multiple sites in nerve cells A: Lung inflammation; headache; impaired speech C: Inflammation of gums; appetite loss; encephalopathy; including tremor; irritability |

|

Calomel Hg2Cl2 |

Laboratories |

A: Low acute toxicity chronic toxic effects, see above |

|

|

Sublimate HgCl2 |

Disinfection |

Hospitals; clinics; laboratories |

M: Acute tubular and glomerular renal degeneration. Verytoxic even in small oral doses, lethal down to 30 mg/kgweight C: See above. |

|

Manganese |

Melting (steel alloy); cutting; welding in steel; dry batteries |

Manganese mining; steel and aluminium production; metal industry; battery production; chemical industry; brickyard |

M: Not known, possible changes in dopamine and catecholamine in basal ganglia in the centre of the brain A: Dysphoria C: Encephalopathy including Parkinsonism; psychosis; appetite loss; irritability; headache; weakness |

|

Aluminium |

Metallurgy; grinding; polishing |

Metal industry |

M: Unknown C: Possibly encephalopathy |

1 M: mechanism; A: acute effects; C: chronic effects.

Neuropathy: dysfunction of motor- and sensory peripheral nerve fibres.

Encephalopathy: brain dysfunction due to generalized impairment of the brain.

Monomers

Monomers constitute a large, heterogeneous group of reactive chemicals used for chemical synthesis and production of polymers, resins and plastics. Monomers comprise polyhalogenated aromatic compounds such as p-chlorobenzene and 1,2,4-trichlorbenzene; unsaturated organic solvents such as styrene and vinyltoluene, acrylamide and related compounds, phenols, ɛ-caprolactam and ζ-aminobutyrolactam. Some of the widely used neurotoxic monomers and their effect on the nervous system are listed in Table 3. Occupational exposure to neurotoxic monomers may take place at industries manufacturing, transporting and using chemical products and plastic products. During handling of polymers containing rest monomers, and during moulding in boat yards and in dental clinics, a substantial exposure to neurotoxic monomers takes place. Upon exposure to these monomers uptake may take place during inhalation (e.g., carbon disulphide and styrene) or by skin contact (e.g., acrylamide). As monomers are a heterogeneous group of chemicals, several different mechanisms of toxicity are likely. This is reflected by differences in symptoms (Table 4).

Table 4. Neurotoxic monomers

|

Compound |

Examples of source of exposure |

Selected industries at risk |

Effects1 |

|

Acrylamide |

Employees exposed to the monomer |

Polymer production; tunnelling and drilling operations |

M: Impaired axonal transport C: Polyneuropathy; dizziness; tremor and ataxia |

|

Acrylonitrile |

Accidents in labs and industries; house fumigation |

Polymer and rubber production; chemical synthesis |

A: Hyperexcitability; salivation; vomiting; cyanosis; ataxia; difficulty breathing |

|

Carbon disulphide |

Production of rubber and viscose rayon |

Rubber and viscose rayon industries |

M: Impaired axonal transport and enzyme activity is likely C: Peripheral neuropathy; encephalopathy; headache; vertigo; gastrointestinal disturbances |

|

Styrene |

Production of glass-reinforced plastics; monomer manufacture and transportation; use of styrene-containing resins and coatings |

Chemical industry; fibreglass production; polymer industry |

M: Unknown A: Central nervous system depression; headache C: Polyneuropathy; encephalopathy; hearing loss |

|

Vinyltoluene |

Resin production; insecticide compounds |

Chemical and polymer industry |

C: Polyneuropathy; reduced motor nerve conductionvelocity |

1 M: mechanism; A: acute effects; C: chronic effects.

Neuropathy: dysfunction of motor and sensory peripheral nerve fibres.

Encephalopathy: brain dysfunction due to generalized impairment of the brain.

Ataxia: impaired motor coordination.

Organic solvents