16. Occupational Health Services

Chapter Editors: Igor A. Fedotov, Marianne Saux and Jorma Rantanen

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Standards, Principles and Approaches in Occupational Health Services

Jorma Rantanen and Igor A. Fedotov

Occupational Health Services and Practice

Georges H. Coppée

Medical Inspection of Workplaces and Workers in France

Marianne Saux

Occupational Health Services in Small-Scale Enterprises

Jorma Rantanen and Leon J. Warshaw

Accident Insurance and Occupational Health Services in Germany

Wilfried Coenen and Edith Perlebach

Occupational Health Services in the United States: Introduction

Sharon L. Morris and Peter Orris

Governmental Occupational Health Agencies in the United States

Sharon L. Morris and Linda Rosenstock

Corporate Occupational Health Services in the United States: Services Provided Internally

William B. Bunn and Robert J. McCunney

Contract Occupational Health Services in the United States

Penny Higgins

Labour Union-Based Activities in the United States

Lamont Byrd

Academic-Based Occupational Health Services in the United States

Dean B. Baker

Occupational Health Services in Japan

Ken Takahashi

Labour Protection in the Russian Federation: Law and Practice

Nikolai F. Izmerov and Igor A. Fedotov

The Practice of Occupational Health Service in the People’s Republic of China

Zhi Su

Occupational Safety and Health in the Czech Republic

Vladimír Bencko and Daniela Pelclová

Practising Occupational Health in India

T. K. Joshi

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Principles for occupational health practice

2. Doctors with specialist knowledge in occ. medicine

3. Care by external occupational medical services

4. US unionized workforce

5. Minimum requirements, in-plant health

6. Periodic examinations of dust exposures

7. Physical examinations of occupational hazards

8. Results of environmental monitoring

9. Silicosis & exposure, Yiao Gang Xian Tungsten Mine

10. Silicosis in Ansham Steel company

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Occupational Safety and Health in the Czech Republic

Geopolitical Background

The predominant development of heavy industry (the iron and steel industry, smelting and refinery plants), metalworking and machinery industries, and the emphasis on the production of energy in Central and Eastern Europe, have significantly predetermined the structure of the economies in the region for the last four decades. This state of affairs has resulted in the relatively high exposures to certain types of occupational hazards in the workplace. Current efforts to transform the existing economies along the lines of the market economy model and to improve occupational safety and health have been considerably successful so far, given the short period of time for such an endeavour.

Until recently, ensuring the prevention of adverse health effects of chemicals present in occupational settings and in the environment, the drinking water and the food basket of the population was provided for by the compulsory observance of hygienic and sanitary standards and occupational exposure limits such as Maximum Allowable Concentrations (MACs), Threshold Limit Values (TLVs) and Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI). The principles of toxicity testing and exposure evaluation recommended by various international organizations, including standards applied in the countries of the European Union, will become more and more compatible with those used in the Central and Eastern European countries as the latter gradually integrate with other European economies.

During the 1980s the need was increasingly recognized to harmonize the methodologies and scientific approaches in the field of toxicology and hygienic standardization applied in the OECD countries with those used in the member countries of the Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA). This was mainly due to growing levels of production and trade, including industrial and agricultural chemicals. A contributing factor favouring the urgency with which these considerations were viewed was a growing problem of air and river pollution across national boundaries in Europe (Bencko and Ungváry 1994).

The Eastern and Central European economic model was based on a centrally planned economic policy oriented to the development of basic metal industries and the energy sector. As of 1994, except for minor changes, the economies of the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, and the Czech and the Slovak Republics had preserved their old structures (Pokrovsky 1993).

Coal mining is a widely developed industry in the Czech Republic. At the same time, black coal mining (e.g., in the northern Moravian region of the Czech Republic) is a cause of 67% of all new cases of pneumoconioses in the country. Brown coal is extracted in opencast mines in northern Bohemia, southern Silesia and neighbouring parts of Germany. Thermal power stations, chemical plants and brown coal mining heavily contributed to the environmental pollution of this region, forming the so-called “black” or “dirty triangle” of Europe. Uncontrolled use of pesticides and fertilizers in agriculture was not exceptional (Czech and Slovak Federal Republic 1991b).

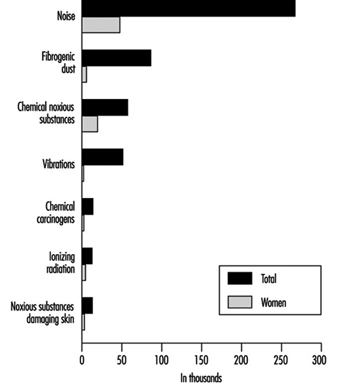

The labour force of the Czech Republic numbers some 5 million employees. About 405,500 workers (that is, 8.1% of the working population) are involved in hazardous operations (Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic 1992). Figure 1 presents data on the number of workers exposed to different occupational hazards and the proportion of women among them.

Figure 1. Number of workers in the Czech Republic exposed to the most serious occupational risks

Changing Needs

The occupational health system of the Czech Republic underwent three consecutive stages in its development and was influenced by the political and economic changes in the country (Pelclová, Weinstein and Vejlupková 1994).

Stage 1: 1932-48. This period was marked by the foundation of the first Department of Occupational Medicine by Professor J. Teisinger at the oldest university in Central Europe—Charles University (founded in 1348). Later, in 1953, this department became the Clinic of Occupational Medicine, with 27 beds. Professor Teisinger also founded the Research Institute of Occupational Health and in 1962 the Poison Information Centre at the Clinic. He was granted several international awards, including an award from the American Association of Industrial Hygienists in 1972 for his personal contribution to occupational health development.

Stage 2: 1949-88. This period exhibited numerous inconsistencies, in some respects being marked by notable deficiencies and in others showing distinct advantages. It was recognized that the existing system of occupational health, in many ways reliable and well developed, nevertheless had to be reorganized. Health care was considered as a basic civil right guaranteed by the Constitution. The six basic principles of the health system (Czech and Slovak Federal Republic 1991a) were:

- planned integration of health care into the society

- promotion of a healthy lifestyle

- scientific and technical development

- prevention of physical and mental illnesses

- free and universal access to health care services

- concern on the part of the state for a healthy environment.

Despite certain progress none of these goals had been fully achieved. Life expectancy (67 years for men and 76 years for women) is the shortest among the industrialized countries. There is a high mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases and cancer. About 26% of adult Czechs are obese and 44% of them have cholesterol levels above 250 mg/dl. The diet contains much animal fat and is low in fresh vegetables and fruits. Alcohol consumption is relatively high, and around 45% of adults smoke; smoking kills about 23,000 persons a year.

Medical care, dental care and medicines were provided free of charge. The numbers of physicians (36.6 per 10,000 inhabitants) and nurses (68.2 per 10,000) were among the highest in the world. But in the course of time the government became unable to cover the continually increasing and abundant expenses needed for public health. There had been temporary shortages of some drugs and equipment as well as difficulties in providing health care services and rehabilitation. The existing structure, which did not allow a patient to choose his primary health care physician, created many problems. Medical staff working in the state-run hospitals received low fixed salaries and had no incentives to provide more health care services. A private health care system did not exist. In hospitals, the main criterion of acceptable functioning was the “percentage of occupied beds” and not the quality of the health care provided.

However, there were positive features of the state-run centralized system of occupational health. One of them was an almost complete registration of hazardous workplaces and a well-organized system of hygienic control provided by the Hygienic Service. In-plant occupational health services established in large industrial enterprises facilitated the provision of comprehensive health care services, including periodic medical examinations and treatment of workers. Small private enterprises, which usually pose many problems to occupational health programmes, did not exist.

The situation was similar in agriculture, where there were no small private farms, but large-scale cooperative ones: an occupational physician working in a health centre of a factory or a cooperative farm provided occupational health services for the workers.

Enforcement of occupational safety and health legislation was sometimes contradictory. After an inspection of a hazardous workplace was carried out by an industrial hygienist or factory inspector, who had required the reduction of the level of occupational exposure and the enforcement of prescribed health and safety standards, rather than correct the hazards the workers would receive monetary compensation instead. Besides the fact that enterprises often took no action at all to improve working conditions, the workers themselves were not interested in improving their working conditions but opted to continue receiving bonuses in lieu of changes in the working environment. Furthermore, a worker who contracted an occupational disease received a substantial monetary recompense according to the severity of the disease and to the level of his or her previous salary. Such a situation produced conflicts of interests among industrial hygienists, occupational physicians, trade unions and enterprises. As many of the benefits were paid by the state and not by the enterprise, the latter often found it cheaper not to improve safety and health in the workplace.

Strange as it may seem, some hygienic standards, including permissible levels and occupational exposure limits, were more rigorous than those in the United States and in the western European countries. Thus, it was sometimes impossible not to exceed them with outdated machinery and equipment. Workplaces exceeding the limits were classified under “category 4”, or most hazardous, but for economic reasons manufacturing was not stopped and workers were offered compensatory benefits instead.

Stage 3: 1989–the present. The “velvet revolution” of 1989 enabled an inevitable change of the public health care system. The reorganization has been rather complex and sometimes difficult to accomplish: consider, for example, that the health care system has more beds in hospitals and doctors per 10,000 inhabitants than any industrialized country while it uses disproportionately less financial resources.

The Current Status of Occupational Safety and Health

The most frequent occupational hazard at the workplace in the Czech Republic is noise—about 65.8% of all workers at risk are exposed to this occupational hazard (Figure 8). The second major work-related hazard is fibrogenic dust, which represents an occupational hazard to about 21.3% of all workers at risk. Approximately 14.3% of workers are exposed to toxic chemicals. More than one thousand of these are exposed to toluene, carbon monoxide, lead, gasoline, benzene, xylene, organophosphorus compounds, cadmium, mercury, manganese, trichlorethylene, styrene, tetrachloroethylene, aniline and nitrobenzene. Another physical hazard—local hand-arm vibration—is a danger for 10.5% of all workers at risk. Other workers are exposed to chemical carcinogens, ionizing radiation and dangerous substances causing skin lesions.

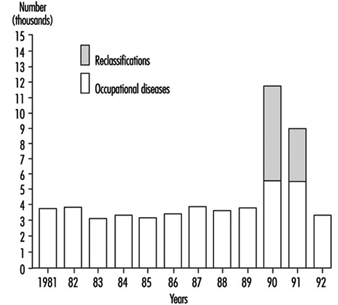

The number of acknowledged cases of occupational disease in the Czech Republic in 1981-92 is presented in figure 2.

Figure 2. Occupational diseases in the Czech Republic in the period 1981-1992

The increase of morbidity from occupational diseases in 1990–91 had been due to the process of reclassification of occupational illnesses requested by miners and workers in other occupations and by their trade unions. They asked to change the status of “being endangered with an occupational disease”, used for less obvious forms of occupational impairment with low compensation, to fully compensated disease. The status of “endangerment” was reconsidered by the Ministry of Health in 1990 for the following kinds of occupational pathology:

- mild forms of pneumoconioses

- mild forms of chronic musculoskeletal disorders due to overload and vibration

- mild forms of occupational hearing loss.

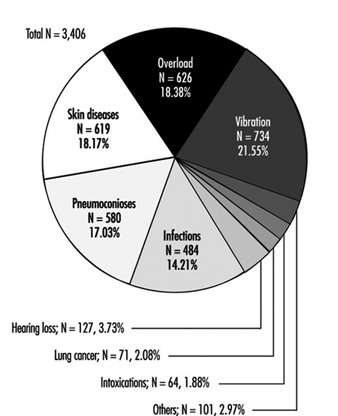

Reclassification was done for all cases before 1990 and concerned 6,272 cases in 1990 and 3,222 cases in 1991 (figure 2). After that the status of “endangerment” was abolished. Figure 3 presents data on 3,406 new cases of occupational diseases by category diagnosed in the Czech Republic in 1992; 1,022 cases of these occupational diseases were diagnosed in women (Urban, Hamsova and Neecek 1993).

Figure 3. Occupational diseases in the Czech Republic in 1992

Some shortages in the supply of measuring equipment for sampling and analysis of toxic substances make it difficult to conduct occupational hygiene evaluations in the workplace. On the other hand, the use of biomarkers in exposure tests for the monitoring of workers in hazardous occupations is practised for a variety of dangerous substances according to the regulations of the Czech Republic. Similar tests have already been legally codified in Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia, Poland, and in some other countries of Central and Eastern Europe. The use of exposure tests for periodic medical examinations has proved to be a very efficient tool for personnel exposure monitoring. This practice has enabled early detection of some occupational diseases and permitted their prevention, thus decreasing compensation costs.

The transition to the market economy and the rising costs of health care services in the Czech Republic have had their influence on occupational health services. In the past, the in-plant based occupational health service or centre provided both health surveillance and treatment for workers. Nowadays, these activities are subjected to some restrictions. This has resulted in reduced activities in health surveillance and hazard control and in an increased number of occupational accidents and diseases. Workers in rapidly emerging small-scale enterprises, which often operate with unreliable machinery and equipment, are practically out of the reach of occupational health professionals.

Projects for the Future

A new system of public health in the Czech Republic is expected to incorporate the following principles:

- prevention and health promotion

- overall access to “standard” health care

- decentralized policy determining delivery of services

- integration of health services in a territorial network

- increased autonomy of health care professionals

- emphasis on outpatient care

- compulsory health insurance

- community participation

- more options for patients

- new public/private sector partnership to provide an “above standard” health care no longer offered by the public sector.

The introduction of the compulsory health insurance system and the creation of the General Health Insurance Office, which began operating in January 1993, as well as minor health insurance companies in the Czech Republic have marked the beginning of reform in the public health sector. These changes have brought some problems to the occupational health services, given their preventive character and the high cost of treatment in hospitals. Thus, the role of outpatient medical settings in treating patients with conventional as well as work-related diseases is steadily increasing.

The Potential Impact of Continuing Changes on Occupational Safety and Health

The growth of reform in the public health sector has created a need for change for occupational physicians, industrial hygienists and in-patient medical settings, and has also led to a focus on prevention. The ability to focus on prevention and milder forms of disease is partly explained by earlier positive results and by the relatively good functioning of the previous occupational health system, which had worked effectively towards eliminating major serious occupational diseases. The changes have involved a shift of attention from severe forms of occupational pathology that needed urgent treatment (such as industrial poisoning and pneumoconioses with respiratory and right-heart failure) to mild forms of disease. The change in the activities of the occupational health services from a curative orientation to early diagnosis now concerns such conditions as mild forms of pneumoconioses, farmer’s lung, chronic liver illnesses and chronic musculoskeletal disorders due to overload or vibration. Preventive measures at the earlier stages of occupational diseases also should be undertaken.

Industrial hygiene activities are not covered by the health insurance system, and the industrial hygienists in the hygienic stations are still paid by the government. Lowering their number and the reorganization of hygienic stations are also expected.

Another change in the health care system is the privatization of some health services. The privatization of small out-patient medical centres has already started. Hospitals—including university hospitals—are not involved in this process at present and details of their privatization still need to be clarified. New legislation concerning the duties of the enterprises, workers and occupational health services is being gradually created.

Occupational Health at the Crossroads

Thanks to the advanced system of occupational health founded by Professor Teisinger in 1932, the Czech Republic does not face a serious problem of education in occupational health for university students, even though in some countries of Central and Eastern Europe the rate of recognized occupational diseases is about five times less than that of the Czech Republic. The Czech List of Occupational Diseases does not differ notably from that appended to the ILO Employment Injury Benefits Convention, (No. 121), (ILO 1964). The proportion of unrecognized principal occupational diseases is low.

The occupational health system in the Czech Republic is now at the crossroads and there is an obvious need for its reorganization. But it is necessary at the same time to preserve whatever positive features have been acquired from experience with the previous occupational health system, namely:

- registration of working conditions at the workplaces

- maintaining in operation a broad system of periodic medical examinations of employees

- provision of curative health care services at large-scale enterprises

- offering a system of vaccination and communicable disease control

- preserving the system whereby occupational health services admit patients with various occupational illnesses, a system that would involve the university hospitals in providing treatment to patients as well as education and training to medical students and graduates.

Practising Occupational Health in India

Workers’ health has been of interest to physicians in India for almost half a century. The Indian Association of Occupational Health was founded in the 1940s in the city of Jamshedpur, which has the country’s best known and oldest steel plant. However, multidisciplinary occupational health practice evolved in the 1970s and 1980s when the ILO sent a team which helped create a model occupational health centre in India. The industry and workplaces traditionally provided health care under the banner of First Aid Stations/Plant Medical Services. These outfits managed minor health problems and injuries at the worksite. Some companies have recently set up occupational health services, and, hopefully more should follow suit. However, the university hospitals have so far ignored the specialty.

Occupational safety and health practice started off with injuries and accident reporting and prevention. There is a belief, not without reason, that injuries and accidents remain under-reported. The 1990–91 incidence rates of injuries are higher in electricity (0.47 per 1,000 workers employed), basic metal (0.45), chemical (0.32) and non-metallic industries (0.27), and somewhat lower in wood and wood pulp industries (0.08) and machinery and equipment (0.09). The textile industry, employing more workers (1.2 million in 1991) had an incidence rate of 0.11 per 1,000 workers. With regard to fatal injuries, the incidence rates in 1989 were 0.32 per 1,000 workers in coal mines and 0.23 in non-coal mines. In 1992, a total of 20 fatal and 753 non-fatal accidents occurred in ports.

Figures are unavailable for occupational hazards as well as for the number of workers exposed to specific hazards. The statistics published by the Labour Bureau do not show these. The system of occupational health surveillance is yet to develop. The number of occupational diseases reported is abysmal. The number of diseases reported in 1978 was just 19, which climbed to 84 in 1982. There is no pattern or trend visible in the reported diseases. Benzene poisoning, halogen poisoning, silicosis and pneumoconiosis, byssinosis, chrome ulceration, lead poisoning, hearing loss and toxic jaundice are the conditions reported most frequently.

There is no comprehensive occupational health and safety legislation. The three principal acts are: the Factories Act, 1948; the Mines Act, 1952; and the Dock Workers Safety, Health and Welfare Act, 1986. A bill for construction workers’ safety is planned. The Factories Act, first adopted in 1881, even today covers workers only in the registered factories. Thus a large number of blue- as well as white-collar workers do not qualify for occupational safety and health benefits under any law. The inadequacy of law and poor enforcement are responsible for a not very satisfactory state of occupational health in the country.

Most occupational health services in industry are managed by either doctors or nurses, and there are few with multidisciplinary disposition. The latter are confined to large industry. The private industry and large public sector plants located in remote areas have their own townships and hospitals. Occupational medicine and occasionally industrial hygiene are the two common disciplines in most occupational health services. Some services have also started hiring an ergonomist. Exposure monitoring and biological monitoring have not received the desired attention. The academic base of occupational medicine and industrial hygiene is not yet well developed. Advanced courses in industrial hygiene and postgraduate degree courses in occupational health practice in the country are not widely available.

When Delhi became a state in 1993, the Health Ministry came to be headed by a health professional who reaffirmed his commitment to improving public and preventive health care. A committee set up to study the issue of occupational and environmental health recommended setting up an occupational and environmental medicine clinic in a prestigious teaching hospital in the city.

Dealing with the complex health problems arising out of environmental pollution and occupational hazards requires more aggressive involvement of the medical community. The teaching university hospital receives hundreds of patients a day, many of whom have exposure to hazardous materials at work and to the unhealthy urban environment. Detection of occupationally and environmentally induced health disorders requires inputs from many clinical specialists, imaging services, laboratories and so on. Owing to the advanced nature of disease, some supportive treatment and medical care becomes essential. Such a clinic enjoys the sophistication of a teaching hospital, and following detection of the health disorder, treatment or rehabilitation of the victim as well as the suggested intervention to protect others can be more effective as teaching hospitals enjoy more authority and command more respect.

The clinic has expertise in the area of occupational medicine. It intends to collaborate with the labour department, which has an industrial hygiene laboratory developed with liberal assistance under an ILO scheme to strengthen occupational safety and health in India. This will make the task of hazard identification and hazard evaluation easier. Medical practitioners will be advised about health assessment of the exposed groups at the point of entry and periodically, and regarding record keeping. The clinic will help sort out the complicated cases and ascertain work-relatedness. The clinic will offer expertise to industry and workers on health education and safe practices with regard to the use and handling of hazardous materials in the workplace. This should make primary prevention more easily achievable and will strengthen occupational health surveillance as envisaged under the ILO Convention on Occupational Health Services (No. 161) (ILO 1985a).

The clinic is being developed in two phases. The first phase is focusing on identifying hazards and creating a database. This phase will also emphasize the creation of awareness and developing outreach strategies with regard to hazardous working environments. The second phase will focus on strengthening exposure monitoring, medical toxicological evaluation and ergonomic inputs. The clinic plans to popularize occupational health teaching for undergraduate medical students. The postgraduate students working on dissertations are being encouraged to choose topics from the field of occupational and environmental medicine. A postgraduate student has recently completed a successful project on acquired blood-borne infections among health care workers in the hospitals.

The clinic also intends to take up environmental concerns, namely the adverse effects of noise and rising pollution, as well as the adverse effects of environmental lead exposure on children. In the long run education of primary health care providers and community groups is also planned through the clinic. The other goal is to create registers of prevalent occupational diseases. The involvement of several clinical specialists in occupational and environmental medicine is also going to create an academic nucleus for the future, when a higher postgraduate qualification hitherto unavailable in the country can be undertaken.

The clinic was able to draw the attention of enforcement and regulatory agencies towards the serious health risks to fire fighters when they fought a major polyvinyl chloride fire in the city. The media and environmentalists were only talking of risks to the community. It is hoped that such clinics will in the future be set up in all major city hospitals; they are the only way to involve senior medical specialists in occupational and environmental medicine practice.

Conclusion

There is an urgent need in India to introduce a Comprehensive Occupational Health and Safety Act in line with many indus-trialized countries. This should be associated with the creation of an appropriate authority to supervise its implementation and enforcement. This will enormously help ensure a uniform standard of occupational health care in all states. At present there is no linkage between the various occupational health care centres. Providing quality training in industrial hygiene, medical toxico-logy and occupational epidemiology are other priorities. Good analytical laboratories are required, which should be certified to ensure quality. India is a very rapidly industrializing country, and this pace will continue into the next century. Failing to address these issues will lead to incalculable morbidity and absenteeism as a consequence of work-related health problems. This will undermine the productivity and competitiveness of industry, and gravely affect the country’s resolve to eliminate poverty.

" DISCLAIMER: The ILO does not take responsibility for content presented on this web portal that is presented in any language other than English, which is the language used for the initial production and peer-review of original content. Certain statistics have not been updated since the production of the 4th edition of the Encyclopaedia (1998)."