Women's Health

There is a common misperception that, outside of reproductive differences, female and male workers will be similarly affected by workplace health hazards and attempts to control them. While women and men do suffer from many of the same disorders, they differ physically, metabolically, hormonally, physiologically and psychologically. For example, women’s smaller average size and muscle mass dictate special attention to the fitting of protective clothing and devices and the availability of properly designed hand tools, while the fact that their body mass is usually smaller than that of men makes them more susceptible, on average, to the effects of alcohol abuse on the liver and the central nervous system.

They also differ in the types of job they hold, in the social and economic circumstances that influence their lifestyles, and in their participation in and response to health promotion activities. Although there have been some recent changes, women are still more likely to be found in jobs that are stultifyingly routine and in which they are exposed to repetitive injury. They suffer from pay inequity and are much more likely than men to be burdened with homemaking responsibilities and the care of children and elderly dependants.

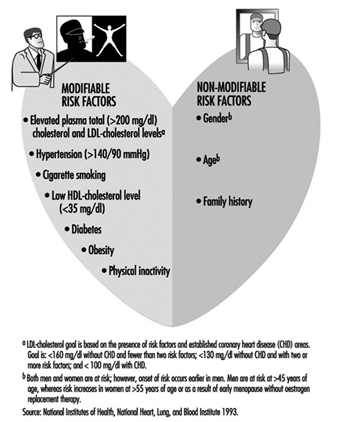

In industrialized countries women have a longer life expectancy than men; this applies to every age group. At age 45, a Japanese woman may expect to live on average another 37.5 years, and a 45-year-old Scottish woman another 32.8 years, with women from most of the other countries of the developed world falling between these limits. These facts lead to an assumption that women are, therefore, healthy. There is a lack of awareness that these “extra” years are frequently marred by chronic illness and disability much of which is preventable. Many women know far too little about the health risks they face and, therefore, about the measures they can take to control those risks and protect themselves against serious disease and injury. For example, many women are rightfully concerned about breast cancer but ignore the fact that heart disease is by far the major cause of death in women and that, owing primarily to the increase in their cigarette smoking—which is also a major risk factor for coronary artery disease—the incidence of lung cancer among women is increasing.

In the United States, a 1993 national survey (Harris et al. 1993), involving interviews of more than 2,500 adult women and 1,000 adult men, confirmed that women suffer from serious health problems and that many do not receive the care they need. Between three and four out of ten women, the survey found, are at risk for undetected treatable disease because they are not receiving appropriate clinical preventive services, largely because they lack health care insurance or because their doctors never suggested that appropriate tests were available and should be sought. Furthermore, a substantial number of the American women surveyed were not happy with their personal physicians: four out of ten (twice the proportion of men) said their physicians “spoke down” to them and 17% (compared to 10% of men) had been told that their symptoms were “all in the head”.

While overall rates of mental illness are roughly the same for men and women, the patterns are different: women suffer more from depression and anxiety disorders while drug and alcohol abuse and antisocial personality disorders are more common among men (Glied and Kofman 1995). Men are more likely to seek and receive care from mental health specialists while women are more often treated by primary care physicians, many of whom lack the interest if not the expertise to treat mental health problems. Women, especially older women, receive a disproportionate share of the prescriptions for psychotropic drugs, so that concern has arisen that these drugs are possibly being overutilized. All too often, difficulties stemming from inordinate levels of stress or from problems that are preventable and treatable are explained away by health professionals, family members, supervisors and co-workers, and even by women themselves, as being reflective of the “time of the month” or “change of life”, and, therefore, go untreated.

These circumstances are compounded by the assumption that women—young and old alike—know all there is to know about their bodies and how they function. This is far from the truth. There exists widespread ignorance and uncritically accepted misinformation. Many women feel ashamed to reveal their lack of knowledge and are being needlessly worried by symptoms that are in fact either “normal” or simply explained.

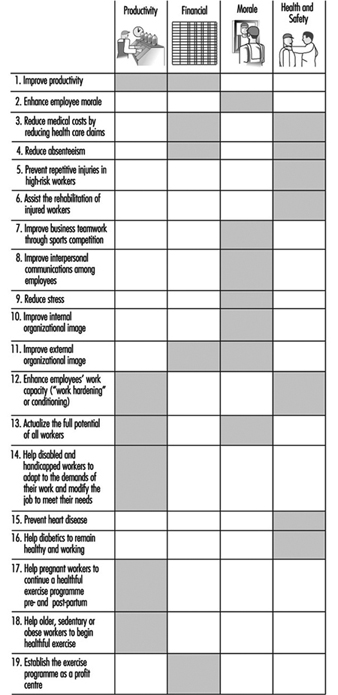

As women constitute some 50% of the workforce in a large section of the employment arena, and considerably more in some service industries, the consequences of their preventable and correctable health problems levy a significant and avoidable toll on their well-being and productivity and on the organization as well. That toll may be considerably reduced by a worksite health promotion program designed for women.

Worksite Health Promotion for Women

A good deal of health information is provided by newspapers and magazines and on television but much of that is incomplete, sensationalized or geared to the promotion of particular products or services. Too often, in reporting on current medical and scientific advances, the media raise more questions than they answer and even cause needless anxiety. Health care professionals in hospitals, clinics and private offices often fail to make sure that their patients are properly educated about the problems they present, to say nothing of taking the time to inform them about important health issues unrelated to their symptoms.

A properly designed and administered worksite health promotion program should provide accurate and complete information, opportunities to ask questions either in group or individual sessions, clinical preventive services, access to a variety of health promotion activities and counseling about adjustments that may prevent or minimize distress and disability. The worksite offers an ideal venue for the sharing of health experiences and information, particularly when they are relevant to circumstances encountered on the job. One can also take advantage of the peer pressure that is present in the workplace to provide workers with additional motivation for participating and persisting in health promoting activities and in maintaining a healthful lifestyle.

There is a variety of approaches to programming for women. Ernst and Young, the large accounting firm, offered its London employees a series of Health Seminars for Women conducted by an outside consultant. They were attended by all grades of staff and were well received. The women who attended were secure in the format of the presentations. As an outsider, the consultant posed no threat to their employment status, and together they cleared up many areas of confusion about women’s health.

Marks and Spencer, a major retailer in the United Kingdom, conducts a program through its in-house medical department using outside resources to provide services to employees in their many regional worksites. They offer screening examinations and individual advice to all their staff, together with an extensive range of health literature and videotapes, many of which are produced in-house.

Many companies use independent health advisers outside the company. An example in the United Kingdom is the service provided by the BUPA (British United Provident Association) Medical Centers, who see many thousands of women through their network of 35 integrated but geographically scattered units, supplemented by their mobile units. Most of these women are referred through their employers’ health promotion programs; the remainder come independently.

BUPA was probably the first, at least in the United Kingdom, to establish a women’s health centre dedicated to preventive services exclusively for women. Hospital-based and free-standing women’s health centers are becoming more common and are proving attractive to women who have not been well served by the prevailing health care system. In addition to providing prenatal and obstetrical care, they tend to offer broad-ranging primary care, with most placing particular emphasis on preventive services.

The National Survey of Women’s Health Centers, conducted in 1994 by researchers from the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health with support from the Commonwealth Foundation (Weisman 1995), estimated that there are 3,600 women’s health centers in the United States, of which 71% are reproductive health centers providing primarily routine outpatient gynaecological examinations, Pap tests and family planning services. They also provide pregnancy tests, abortion counseling (82%) and abortions (50%), screening and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, breast examinations and blood pressure checks.

Twelve per cent are primary care centers (these include women’s college health services) which provide basic well-woman and preventive care including periodic physical examinations, routine gynaecological examinations and Pap tests, diagnosis and treatment of menstrual problems, menopausal counseling and hormone replacement therapy, and mental health services, including drug and alcohol abuse counseling and treatment.

Breast centers constitute 6% of the total (see below), while the remainder are centers providing various combinations of services. Many of these centers have demonstrated interest in contracting to provide services to female employees of nearby organizations as part of their worksite health promotion programs.

Regardless of the venue, the success of worksite health promotion programming for women hinges not only on the reliability of the information and services offered but, more important, on the manner in which they are presented. The programs must be sensitized to women’s attitudes and aspirations as well as to their concerns and, while being supportive, they should be free of the condescension with which these problems are so often addressed.

The remainder of this article will focus on three categories of problems regarded as particularly important health concerns for women—menstrual disorders, cervical and breast cancer and osteoporosis. However, in addressing other health categories, the worksite health promotion program should ensure that any other problems of particular relevance for women will not be overlooked.

Menstrual Disorders

For the great majority of women, menstruation is a “natural” process that presents few difficulties. The menstrual cycle may be disturbed by a variety of conditions which may cause discomfort or concern for the employee. These may lead her to take sick absence on a regular basis, often reporting a “cold” or “sore throat” rather than a menstrual problem, especially if the absence certificate is to be submitted to a male manager. However, the absence pattern is obvious and referral to a qualified health professional may resolve the problem rapidly. Menstrual problems that may affect the workplace include amenorrhoea, menorrhagia, dysmenorrhoea, the premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and menopause.

Amenorrhoea

While amenorrhoea may create concern, it does not ordinarily affect work performance. The most common cause of amenorrhoea in younger women is pregnancy and in older women it is menopause or a hysterectomy. However, it may also be attributable to the following circumstances:

- Poor nutrition or underweight. The reason for poor nutrition may be socioeconomic in that little food is available or affordable, but it may also be the result of self-starvation related to eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia.

- Excessive exercise. In many developed countries. women train excessively in physical fitness or sports programmes. Even though their food intake may be adequate, they may have amenorrhoea.

- Medical conditions. Problems arising from hypothyroidism or other endocrine disorders, tuberculosis, anaemia from any cause and certain serious, life-threatening diseases can all cause amenorrhoea.

- Contraceptive measures. Medications containing progesterone only will commonly lead to amenorrhoea. It should be noted that sterilization without цphorectomy does not cause a woman’s periods to stop.

Menorrhagia

In the absence of any objective measure of menstrual flow, it is commonly accepted that any flow of menses which is heavy enough to interfere with a woman’s normal day-to-day activities, or which leads to anemia, is excessive. When the flow is heavy enough to overwhelm the normal circulating anti-clotting factor, the woman with “heavy periods” may complain of passing clots. Inability to control the blood flow by any normal sanitary protection can lead to considerable embarrassment in the workplace and may lead to a pattern of regular, monthly one- or two-day absences.

Menorrhagia may be caused by uterine fibroids or polyps. It can also be caused by an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) and, rarely, it may be the first indication of a severe anemia or other serious blood disorder such as leukaemia.

Dysmenorrhoea

Although the vast majority of menstruating women experience some discomfort at the time of menstruation, only a few have pain sufficient to interfere with normal activity and, thus, require referral for medical attention. Again, this problem may be suggested by a pattern of regular monthly absences. Such difficulties associated with menstruation may for certain practical purposes be classified thus:

- Primary dysmenorrhoea. Young women with no evidence of disease may suffer pain on the day before or on the first day of their period that is serious enough to induce them to take time off from work. Although no cause has been found, it is known to be associated with ovulation and, hence, can be prevented by the oral contraceptive pill or by other medication which prevents ovulation.

- Secondary dysmenorrhoea. The onset of painful periods in a woman in her middle thirties or later suggests pelvic pathology and should be fully investigated by a gynaecologist.

It should be noted that some over-the-counter or prescribed analgesics taken for dysmenorrhoea may cause drowsiness and can present a problem for women working in jobs that require alertness to occupational hazards.

Premenstrual syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS), a combination of physical and psychological symptoms experienced by a relatively small percentage of women during the seven or ten days prior to menstruation, has developed its own mythology. It has falsely been credited as the cause of women’s so-called emotionalism and “flightiness”. According to some men, all women suffer from it, while ardent feminists claim that no women have it. In the workplace, it has improperly been cited as a rationale for keeping women out of positions requiring decision making and the exercise of judgment, and it has served as a convenient excuse for denying women promotion to managerial and executive levels. It has been blamed for women’s problems with interpersonal relations and, indeed, in England it has provided the grounds for pleas of temporary insanity that enabled two separate female defendants to escape charges of murder.

The physical symptoms of PMS may include abdominal distention, breast tenderness, constipation, sleeplessness, weight gain due to increased appetite or to sodium and fluid retention, fine-movement clumsiness and inaccuracy in judgment. The emotional symptoms include excessive crying, temper tantrums, depression, difficulty in making decisions, an inability to cope in general and a lack of confidence. They always occur in the premenstrual days, and are always relieved by the onset of the period. Women taking the combined oral contraceptive pill and those who have had oophorectomies rarely get PMS.

The diagnosis of PMS is based on the history of its temporal relationship to menstrual periods; in the absence of definitive causes, there are no diagnostic tests. Its treatment, the intensity of which is determined by the intensity of the symptoms and their effect on normal activities, is empirical. Most cases respond to simple self-help measures which include abolishing caffeine from the diet (tea, coffee, chocolate and most cola soft drinks all contain significant amounts of caffeine), frequent small feedings to minimize any tendency to hypoglycemia, restricting sodium intake to minimize fluid retention and weight gain, and regular moderate exercise. When these fail to control the symptoms, physicians may prescribe mild diuretics (for two to three days only) that control sodium and fluid retention and/or oral hormones that modify ovulation and the menstrual cycle. In general, PMS is treatable and should not represent a significant problem to women in the workplace.

Menopause

Menopause reflecting ovarian failure may occur in women in their thirties or may be postponed to well beyond the age of 50; by the age of 48, about half of all women will have experienced it. The actual time of the menopause is influenced by general health, nutrition and familial factors.

The symptoms of the menopause are diminished frequency of periods usually coupled with scanty menstrual flow, hot flushes with or without night sweats, and a diminution in vaginal secretions, which may cause pain during sexual intercourse. Other symptoms frequently attributed to the menopause include depression, anxiety, tearfulness, lack of confidence, headaches, changes in skin texture, loss of sexual interest, urinary difficulties and sleeplessness. Interestingly, a controlled study involving a symptom questionnaire administered to both men and women showed that a significant portion of these complaints were shared by men of the same age (Bungay, Vessey and McPherson 1980).

The menopause, coming as it does at about the age of 50, may coincide with what has been called the “mid-life transition” or the “mid-life crisis”, terms coined to denote collectively the experiences which seem to be shared by both men and women in their middle years (if anything, they appear to be more common among men). These include loss of purpose, dissatisfaction with one’s job and with life in general, depression, waning interest in sexual activity and a tendency to diminished social contacts. It may be precipitated by the loss of spouse or partner through separation or death or, as regards one’s job, by failure to win an expected promotion or by separation, whether by termination or voluntary retirement. In contrast to menopause, there is no known hormonal basis for the mid-life transition.

Particularly in women, this period may be associated with the “empty nest syndrome,” the sense of purposelessness that may be felt when, their children having left the home, their whole perceived raison d’être seems to have been lost. In such cases, the job and the social contacts in the workplace often provide a stabilizing, therapeutic influence.

Like many of the other “female problems,” menopause has developed its own mythology. Preparatory education debunking these myths supplemented by sensitive supportive counseling will go far to preventing significant dislocations. Continuing to work and maintaining her satisfactory performance on the job may be of crucial value in sustaining a woman’s well-being at this time.

It is at this point that the advisability of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) needs to be considered. Currently the subject of some controversy, HRT was originally prescribed to control menopausal symptoms if they became excessively severe. While usually effective, the hormones commonly used often precipitated vaginal bleeding and, more important, they were suspected of being carcinogenic. As a result, they were prescribed only for limited periods of time, just long enough to control the troublesome menopausal symptoms.

HRT has no effect on the symptoms of the mid-life transition. However, if a woman’s flushes are controlled and she can get a good night’s sleep because her night sweats are prevented, or if she can respond to lovemaking more enthusiastically because it is no longer painful, then some of her other problems may be resolved.

Today, the value of long-term HRT is increasingly being recognized in maintaining the integrity of bone in women with osteoporosis (see below) and in reducing the risk of coronary heart disease, now the highest-ranking cause of death among women in industrialized countries. Newer hormones, combinations and sequences of administration may eliminate the occurrence of planned vaginal bleeding and there appears to be little or no risk of carcinogenesis, even among women with a history of cancer. However, because many physicians are strongly biased for or against HRT, women need to be educated about its benefits and disadvantages so that they can participate confidently in the decision about whether to use it or not.

Recently, calling to mind the millions of women “baby boomers” (children born after the Second World War) who will be reaching the age of menopause within the next decade, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) warned that staggering increases in osteoporosis and heart disease could result unless women are better educated about menopause and the interventions designed to prevent disease and disability and to prolong and enhance their lives after menopause (Voelker 1995). ACOG president William C. Andrews, MD, has proposed a three-pronged program that includes a massive campaign to educate physicians about the menopause, a “perimenopausal visit” to a physician by all women over the age of 45 for a personal risk assessment and in-depth counseling, and involvement of the news media in educating women and their families about the symptoms of menopause and the benefits and risks of treatments like HRT before women reach menopause. The worksite health promotion program can make a major contribution to such an educational effort.

Screening for Cervical and Breast Disease

With regard to women’s needs, a health promotion program should either provide or, at least, recommend periodic screening for cervical and breast cancer.

Cervical disease

Regular screening for precancerous cervical changes by means of the Pap test is a well-established practice. In many organizations, it is made available in the workplace or in a mobile unit brought to it, eliminating the need for female employees to spend time traveling to a facility in the community or visiting their personal physicians. The services of a physician are not required in the administration of this procedure: satisfactory smears may be taken by a well-trained nurse or technician. More important is the quality of the reading of the smears and the integrity of the procedures for record-keeping and reporting of the results.

Breast cancer

Although breast screening by mammography is widely practiced in almost all developed countries, it has been established on a national basis only within the United Kingdom. Currently, over a million women in the United Kingdom are screened, with each woman aged 50 to 64 having a mammogram every three years. All the examinations, including any further diagnostic studies needed to clarify abnormalities in the initial films, are free of charge to the participants. The response to the offer of this three-year cycle of mammography has been over 70%. Reports for the 1993-1994 period (Patnick 1995) show a rate of 5.5% for referral to further assessment; 5.5 women per 1,000 women screened were discovered to have breast cancer. The positive predictive value for surgical biopsy was 70% in this program, compared to some 10% in programs reported elsewhere in the world.

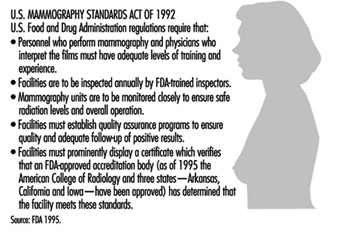

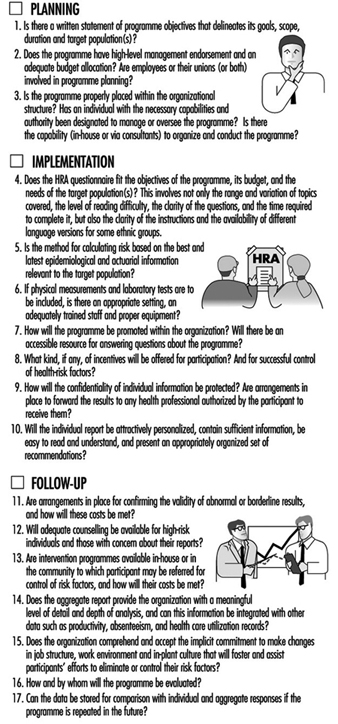

The critical issues in mammography are the quality of the procedure, with particular emphasis on minimizing radiation exposure, and the accuracy of the interpretation of the films. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has promulgated a set of quality regulations proposed by the American College of Radiology that, commencing October 1, 1994, must be observed by the more than 10,000 medical units taking or interpreting mammograms around the country (Charafin 1994). In accordance with the national Mammography Standards Act (enacted in 1992), all mammography facilities in the United States (except those operated by the Department of Veterans Affairs, which is developing its own standards) had to be certified by the FDA as of this date. These regulations are summarized in figure 1.

Figure 1. Mammography quality standards in the United States.

A recent phenomenon in the United States is the increase in the number of breast or breast health centers, 76% of which have appeared since 1985 (Weisman 1995). They are predominantly hospital-affiliated (82%); the others are primarily profit-making enterprises owned by physician groups. About a fifth maintain mobile units. They provide outpatient screening and diagnostic services including physical breast examinations, screening and diagnostic mammography, breast ultrasound, fine-needle biopsy and instruction in breast self-examination. Slightly more than one-third also offer treatment for breast cancer. While primarily focused on attracting self-referrals and referrals by community physicians, many of these centers are making an effort to contract with employer- or labor union-sponsored health promotion programs to provide breast screening services to their female participants.

Introducing such screening programs into the workplace can generate considerable anxiety among some women, particularly those with personal or family histories of cancer and those found to have “abnormal” (or inconclusive) results. The possibility of such non-negative results should be carefully explained in presenting the program, along with the assurance that arrangements are in place for the additional examinations needed to explain and to act upon them. Supervisors should be educated to sanction absences by these women when the necessary follow-up procedures cannot be expeditiously arranged outside of working hours.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone disorder, much more prevalent in women than in men, that is characterized by a gradual decline in bone mass leading to susceptibility to fractures which may result from seemingly innocuous movements and accidents. It represents an important public health problem in most developed countries.

The most common sites for fractures are the vertebrae, the distal portion of the radius and the upper portion of the femur. All fractures at these sites in older individuals should cause one to suspect osteoporosis as a contributing cause.

While such fractures usually occur later in life, after the individual has left the workforce, osteoporosis is a desirable target for worksite health promotion programs for a number of reasons: (1) the fractures may involve retirees and add significantly to their medical care costs, for which the employer may be responsible; (2) the fractures may involve the elderly parents or in-laws of current employees, creating a dependant-care burden that can compromise their attendance and work performance; and (3) the workplace presents an opportunity to educate younger people about the eventual danger of osteoporosis and to urge them to initiate the lifestyle changes that can slow its progress.

There are two types of primary osteoporosis:

- Post-menopausal, which is related to loss of oestrogens and, hence, is more prevalent in women than in men (ratio = 6:1). It is commonly found in the 50-to-70 age group and is associated with vertebral fractures and Colles fractures (of the wrist).

- Involutional, which occurs mainly in those over the age of 70 and is only twice as common among women than in men. It is thought to be due to age-related changes in vitamin D synthesis and is associated chiefly with vertebral and femoral fractures.

Both types may be present simultaneously in women. In addition, in a small percentage of cases, osteoporosis has been attributed to a variety of secondary causes including: hyperparathyroidism; the use of corticosteroids, L-thyroxine, aluminum-containing antacids and other drugs; prolonged bed rest; diabetes mellitus; the use of alcohol and tobacco; and rheumatoid arthritis.

Osteoporosis may be present for years and even decades before fractures result. It can be detected by well-standardized x-ray measurements of bone density, calibrated for age and sex, and supplemented by laboratory evaluation of calcium and phosphorus metabolism. Unusual radiolucency of bone in conventional x rays may be suggestive, but such osteopenia usually cannot be reliably detected until more than 30% of the bone is lost.

It is generally agreed that screening asymptomatic individuals for osteoporosis should not be employed as a routine procedure, especially in worksite health promotion programs. It is costly, not very reliable except in the most well-staffed facilities, involves exposure to radiation and, most important, does not identify those women with osteoporosis who are most likely to have fractures.

Accordingly, although everyone is subject to some degree of bone loss, the prevention program for osteoporosis is focused on those individuals who are at higher risk for its more rapid progression and who are therefore more susceptible to fractures. A special problem is that although the earlier in life the preventive measures are started, the more effective they are, it is nonetheless difficult to motivate younger people to adopt lifestyle changes in the hope of avoiding a health problem that may develop at what many of them consider to be a very remote age of life. A saving grace is that many of the recommended changes are also useful in the prevention of other problems as well as in promoting general health and well-being.

Some risk factors for osteoporosis cannot be changed. They include:

- Race. On average, Whites and Orientals have lower bone density than Blacks matched age for age and are therefore at greater risk.

- Sex. Women have less dense bones than men when matched for age and race and therefore are at greater risk.

- Age. All people lose bone mass with age. The stronger the bones are in youth, the less likely is it that the loss will reach potentially dangerous levels in old age.

- Family history. There is some evidence of a genetic component in the attainment of peak bone mass and the rate of subsequent bone loss; thus, a family history of suggestive fractures in family members may represent an important risk factor.

The fact that these risk factors cannot be altered makes it important to give attention to those that can be modified. Among the measures that may be taken to delay the onset of osteoporosis or to diminish its severity, the following may be mentioned:

- Diet. If adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D are not present in the diet, supplementation is recommended. This is particularly important for people with lactose intolerance who tend to avoid milk and milk products, the major sources of dietary calcium, and is most effective if maintained from childhood until the thirties as peak bone density is being achieved. Calcium carbonate, the most commonly used form of calcium supplementation, frequently causes side effects such as constipation, rebound hyperacidity, abdominal bloating and other gastrointestinal symptoms. Accordingly, many people substitute preparations of calcium citrate which, despite a significantly lower content of elemental calcium, is better absorbed and has fewer side-effects. The amounts of vitamin D present in the usual multivitamin preparation suffice for slowing the bone loss of osteoporosis. Women should be cautioned against excessive doses, which may lead to hypervitaminosis D, a syndrome that includes acute renal failure and increased resorption of bone.

- Exercise. Regular moderate weight-bearing exercise-for example, 45 to 60 minutes of walking at least three times a week-is advisable.

- Smoking. Women who smoke have their menopause on average two years earlier than non-smokers. Without hormone replacement, the earlier menopause will accelerate post-menopausal bone loss. This is another important reason to counter the current trend to increased cigarette smoking among women.

- Hormone replacement therapy. If oestrogen replacement is undertaken, it should be started early in the progress of the menopausal changes since the rate of bone loss is greatest during the first few years after menopause. Because bone loss is resumed after the discontinuation of oestrogen therapy, it should be maintained indefinitely.

Once osteoporosis is diagnosed, treatment is aimed at circumventing further bone loss by following all of the above recommendations. Some recommend using calcitonin, which has been shown to increase total body calcium. However, it must be given parenterally; it is expensive; and there is yet no evidence that it retards or reverses the loss of calcium in the bone or reduces the occurrence of fractures. Biphosphonates are gaining ground as anti-resorptive agents.

It must be remembered that osteoporosis sets the stage for fractures but it does not cause them. Fractures are caused by falls or sudden injudicious movements. While the prevention of falls should be an integral part of every worksite safety program, it is particularly important for individuals who may have osteoporosis. Thus, the health promotion program should include education about safeguarding the environment in both the workplace and in the home (e.g., eliminating or taping down trailing electrical wires, painting the edges of steps or irregularities in the floor, tacking down slippery rugs and promptly drying up any wet spots) as well as sensitizing individuals to such hazards as insecure footwear and seats that are difficult to get out of because they are too low or too soft.

Women’s Health and Their Work

Women are in the paid workforce to stay. In fact, they are the mainstay of many industries. They should be treated as equal to men in every respect; only some aspects of their health experience are different. The health promotion program should inform women about these differences and empower them to seek the kind and quality of health care they need and deserve. Organizations and those who manage them should be educated to understand that most women do not suffer from the problems described in this article, and that, for the small proportion of women who do, prevention or control is possible. Except in rare instances, no more frequent than among men with similar health problems, these problems do not constitute barriers to good attendance and effective work performance.

Many women managers get to their high positions not only because their work is excellent, but because they experience none of the problems of female health that have been outlined above. This can make some of them intolerant and unsupportive of other women who do have such difficulties. One major area of resistance to women’s status in the workplace, it appears, can be women themselves.

A worksite health promotion program that embodies a focus on women’s health issues and problems and addresses them with appropriate sensitivity and integrity can have an important positive impact for good, not only for the women in the workforce, but also for their families, the community and, most important, the organization.

Cancer Prevention and Control

Within the next decade, it is predicted, cancer will become the leading cause of death in many developed countries. This reflects not so much an increase in the incidence of cancer but rather a decrease in mortality due to cardiovascular disease, currently topping the mortality tables. Equally with its high mortality rate, we are disturbed by the specter of cancer as a “dread” disease: one associated with a more or less rapid course of disability and a high degree of suffering. This somewhat fearsome picture is being made easier to contemplate by our growing knowledge of how to reduce risk, by techniques permitting early detection and by new and powerful achievements in the field of therapy. However, the latter may be associated with physical, emotional and economic costs for both the patients and those concerned about them. According to the US National Cancer Institute (NCI), a significant reduction in cancer morbidity and mortality rates is possible if current recommendations relating to use of tobacco, dietary changes, environmental controls, screening and state-of-the-art treatment are effectively applied.

To the employer, cancer presents significant problems entirely apart from the responsibility for possible occupational cancer. Workers with cancer may have impaired productivity and recurrent absenteeism due both to the cancer itself and the side effects of its treatment. Valuable employees will be lost through prolonged periods of disability and premature death, leading to the considerable cost of recruiting and training replacements.

There is a cost to the employer even when it is a spouse or other dependant rather than the healthy employee who develops the cancer. The caregiving burden may lead to distraction, fatigue and absenteeism which tax that employee’s productivity, and the often considerable medical expenses increase the cost of employer-sponsored health insurance. It is entirely appropriate, therefore, that cancer prevention should be a major focus of worksite wellness programs.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention involves avoidance of smoking and modifying other host factors that may influence the development of cancer, and identifying potential carcinogens in the work environment and eliminating or at least limiting workers’ exposure to them.

Controlling exposures

Potential as well as proven carcinogens are identified through basic scientific research and by epidemiological studies of exposed populations. The latter involves industrial hygiene measurements of the frequency, magnitude and duration of the exposures, coupled with comprehensive medical surveillance of the exposed workers, including analysis of causes of disability and death. Controlling exposures involves the elimination of these potential carcinogens from the workplace or, when that is not possible, minimizing exposure to them. It also involves the proper labeling of such hazardous materials and continuing education of workers with respect to their handling, containment and disposal.

Smoking and cancer risk

Approximately one-third of all cancer deaths and 87% of all lung cancers in the US are attributable to smoking. Tobacco use is also the principal cause of cancers of the larynx, oral cavity and oesophagus and it contributes to the development of cancers of the bladder, pancreas, kidney, and uterine cervix. There is a clear dose-response relationship between lung cancer risk and daily cigarette consumption: those who smoke more than 25 cigarettes a day have a risk that is about 20 times greater than that of non-smokers.

Experts believe that the involuntary intake of the tobacco smoke emitted by smokers (“environmental tobacco smoke”) is a significant risk factor for lung cancer in non-smokers. In January 1993, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classified environmental tobacco smoke as a known human carcinogen which, it estimated, is responsible for approximately 3,000 lung cancer deaths annually among US non-smokers.

The 1990 US Surgeon General’s report on the health benefits of smoking cessation provides clear evidence that quitting smoking at any age is beneficial to one’s health. For example, five years after quitting, former smokers experience a diminished risk for lung cancer; their risk, however, remains higher than that of non-smokers for as long as 25 years.

The elimination of tobacco exposure by employer-sponsored/ labor union-sponsored smoking cessation programs and worksite policies enforcing a smoke-free working environment represent a major element in most worksite wellness programs.

Modifying host factors

Cancer is an aberration of normal cell division and growth in which certain cells divide at abnormal rates and grow abnormally, sometimes migrating to other parts of the body, affecting the form and function of involved organs, and ultimately causing death of the organism. Recent, continuing biomedical advances are providing increasing knowledge of the carcinogenesis process and are beginning to identify the genetic, humoral, hormonal, dietary and other factors that may accelerate or inhibit it—thus leading to research on interventions that have the potential to identify the early, precancerous process and so to help restore the normal cellular growth patterns.

Genetic factors

Epidemiologists continue to accumulate evidence of familial variations in the frequency of particular types of cancer. These data have been bolstered by molecular biologists who have already identified genes that appear to control steps in cellular division and growth. When these “tumor suppressor” genes are damaged by naturally-occurring mutations or the effects of an environmental carcinogen, the process may go out of control and a cancer is initiated.

Heritable genes have been found in patients with cancer and members of their immediate families. One gene has been associated with a high risk of colon cancer and endometrial or ovarian cancer in women; another with a high risk of breast and ovarian cancer; and a third with a form of malignant melanoma. These discoveries led to a debate about the ethical and sociological issues surrounding DNA testing to identify individuals carrying these genes with the implication that they then might be excluded from jobs involving possible exposure to potential or actual carcinogens. After studying this question, the National Advisory Council for Human Genome Research (1994), raising issues to do with the reliability of the testing, the present effectiveness of potential therapeutic interventions, and the likelihood of genetic discrimination against those found to be at high risk, concluded that “it is premature to offer DNA testing or screening for cancer predisposition outside a carefully monitored research environment”.

Humoral factors

The value of the prostate specific antigen (PSA) test as a routine screening test for prostatic cancer in older men has not been scientifically demonstrated in a clinical trial. However, in some instances, it is being offered to male workers, sometimes as a token of gender equity to balance the offering of mammography and cervical Pap smears to female workers. Clinics providing routine periodic examinations are offering the PSA test as a supplement to and, sometimes, even as a replacement for the traditional digital rectal examination as well as the recently introduced rectal ultrasound examination. Although its use appears to be valid in men with prostatic abnormalities or symptoms, a recent multinational review concludes that measurement of PSA should not be a routine procedure in screening healthy male populations (Adami, Baron and Rothman 1994).

Hormonal factors

Research has implicated hormones in the genesis of some cancers and they have been used in the treatment of others. Hormones, however, do not appear to be an appropriate item to emphasize in workplace health promotion programs. A possible exception would be warnings of their potential carcinogenic hazard in certain cases when recommending hormones for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and the prevention of osteoporosis.

Dietary factors

Researchers have estimated that approximately 35% of all cancer mortality in the US may be related to diet. In 1988, the US Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health indicated that cancers of the lung, colon-rectum, breast, prostate, stomach, ovary and bladder may be associated with diet. Research indicates that certain dietary factors—fat, fiber, and micronutrients such as beta-carotene, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E and selenium—may influence cancer risk. Epidemiological and experimental evidence indicates that modulation of these factors in the diet can reduce the occurrence of some types of cancer.

Dietary fat

Associations between excess intake of dietary fat and the risk of various cancers, particularly cancers of the breast, colon and prostate, have been demonstrated in both epidemiological and laboratory studies. International correlational studies have shown a strong association between the incidence of cancers at these sites and total dietary fat intake, even after adjusting for total caloric intake.

In addition to the amount of fat, the type of fat consumed may be an important risk factor in cancer development. Different fatty acids may have various site-specific tumor-promoting or tumor-inhibiting properties. Intake of total fat and saturated fat has been strongly and positively associated with colon, prostate, and post-menopausal breast cancers; intake of polyunsaturated vegetable oil has been positively associated with post-menopausal breast and prostate cancers, but not with colon cancer. Conversely, consumption of highly polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids found in certain fish oils may not affect or may even decrease the risk of breast and colon cancers.

Dietary fiber

Epidemiological evidence suggests that the risk of certain cancers, particularly colon and breast cancers, may be lowered by increased intake of dietary fiber and other dietary constituents associated with high intakes of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains.

Micronutrients

Epidemiological studies generally show an inverse relationship between cancer incidence and intake of foods high in several nutrients having antioxidant properties, such as beta-carotene, vitamin C (ascorbic acid), and vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol). A number of studies have shown that low intakes of fruits and vegetables are associated with increased risk of lung cancer. Deficiencies of selenium and zinc have also been implicated in increased cancer risk.

In a number of studies in which the use of antioxidant supplements was shown to reduce the expected number of serious heart attacks and strokes, the data on cancer were less clear. However, results from the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene (ATBC) Lung Cancer Prevention clinical trial, conducted by the NCI in collaboration with the National Public Health Institute of Finland, indicated that vitamin E and beta-carotene supplements did not prevent lung cancer. Vitamin E supplementation also resulted in 34% fewer prostate cancers and 16% fewer colorectal cancers, but those subjects taking beta-carotene had 16% more lung cancers, which was statistically significant, and had slightly more cases of other cancers than those taking vitamin E or the placebo. There was no evidence that the combination of vitamin E and beta-carotene was better or worse than either supplement alone. The researchers have not yet determined why those taking beta-carotene in the study were observed to have more lung cancers. These results suggest the possibility that a different compound or compounds in foods which have high levels of beta-carotene or vitamin E may be responsible for the protective effect observed in epidemiological studies. The researchers also speculated that the length of time of supplementation may have been too short to inhibit the development of cancers in long-term smokers. Further analyses of the ATBC study, as well as results from other trials in progress, will help resolve some of the questions that have arisen in this trial, particularly the question of whether large doses of beta-carotene may be harmful to smokers.

Alcohol

Excessive use of alcoholic beverages has been associated with cancer of the rectum, pancreas, breast and liver. There is also strong evidence supporting a synergistic association of alcohol consumption and tobacco use with increased risk of cancer of the mouth, pharynx, oesophagus and larynx.

Dietary recommendations

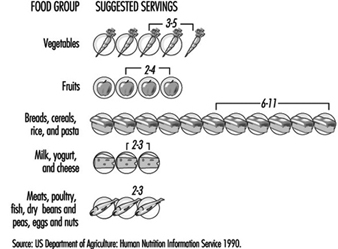

Based on the compelling evidence that diet is related to cancer risk, the NCI has developed dietary guidelines that include the following recommendations:

- Reduce fat intake to 30% or less of calories.

- Increase fibre intake to 20 to 30 grams per day, with an upper limit of 35 grams.

- Include a variety of vegetables and fruits in the daily diet.

- Avoid obesity.

- Consume alcoholic beverages in moderation, if at all.

- Minimize consumption of salt-cured (packed in salt), salt-pickled (soaked in brine), or smoked foods (associated with increased incidence of stomach and oesophageal cancer).

These guidelines are intended to be incorporated into a general dietary regimen that can be recommended for the entire population.

Infectious diseases

There is increasing knowledge of the association of certain infectious agents with several types of cancer: for example, the hepatitis B virus with liver cancer, the human papillomavirus with cervical cancer, and the Epstein-Barr virus with Burkitt’s lymphoma. (The frequency of cancer among patients with AIDS is attributable to the patient’s immunodeficiency and is not a direct carcinogenic effect of the HIV agent.) A vaccine for hepatitis B is now available that, when given to children, ultimately will reduce their risk for liver cancer.

Worksite Cancer Prevention

To explore the potential of the workplace as an arena for the promotion of a broad set of cancer prevention and control behaviors, the NCI is sponsoring the Working Well Project. This project is designed to determine whether worksite-based interventions to reduce tobacco use, achieve cancer preventive dietary modifications, increase screening prevalence and reduce occupational exposure can be developed and implemented in a cost-effective way. It was initiated in September 1989 at the following four research centers in the United States.

- M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas

- University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida

- Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts

- Miriam Hospital/Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island

The project involves approximately 21,000 employees at 114 different worksites around the United States. Most of the selected worksites are involved predominantly in manufacturing; other types of worksites in the project included fire stations and newspaper printers. Tobacco reduction and dietary modification were areas of intervention included in all of the worksites; however, each site maximized or minimized particular intervention programs or included additional options to meet the climatic and socioeconomic conditions of the geographic area. The centers in Florida and Texas, for example, included and emphasized skin cancer screening and the use of sun screens because of increased exposure to the sun in those geographic regions. The centers in Boston and Texas offered programs that emphasized the relationship between cancer and tobacco use. The Florida centre enhanced the diet modification intervention with supplies of fresh citrus fruits, readily available from the state’s farming and fruit industry. Management-employee consumer boards also were established at the worksites of the Florida centre to work with the food service to ensure that the cafeterias offered fresh vegetable and fruit selections. Several of the worksites participating in the project offered small prizes—gift certificates or cafeteria lunches—for continued participation in the project or for achievement of a desired goal, such as smoking cessation. Reduction of exposure to occupational hazards was of special interest at those worksites where diesel exhaust, solvent use or radiation equipment were prevalent. The worksite-based programs included:

- group activities to generate interest, such as taste testing of various foods

- directed group activities, such as quit-smoking contests

- medical/scientific-based demonstrations, such as

testing, to verify the effect of smoking on the respiratory system

testing, to verify the effect of smoking on the respiratory system - seminars on business practices and policy development aimed at significantly reducing or eliminating occupational exposure to potentially or actually dangerous or toxic materials

- computer-based self-help and self-assessment programmes on cancer risk and prevention

- manuals and self-help classes to help reduce or eliminate tobacco use, achieve dietary modifications, and increase cancer screening.

Cancer education

Worksite health education programs should include information about signs and symptoms that are suggestive of early cancer—for example, lumps, bleeding from the rectum and other orifices, skin lesions that do not appear to heal—coupled with advice to seek evaluation by a physician promptly. These programs might also offer instruction, preferably with supervised practice, in self-examination of the breast.

Cancer screening

Screening for precancerous lesions or early cancer is carried out with a view to their earliest possible detection and removal. Educating individuals about the early signs and symptoms of cancer so that they may seek the attention of a physician is an important part of screening.

A search for early cancer should be included in every routine or periodic medical examination. In addition, mass screenings for particular types of cancer may be carried out in the workplace or in a community facility near the worksite. Any acceptable and justifiable screening of an asymptomatic population for cancer should meet the following criteria:

- The disease in question should represent a substantial burden at the public health level and should have a prevalent, asymptomatic, nonmetastatic phase.

- The asymptomatic, nonmetastatic phase should be recognizable.

- The screening procedure should have reasonable specificity, sensitivity and predictive values; it should be of low risk and low cost, and be acceptable to both the screener and the person being screened.

- Early detection followed by appropriate treatment should offer a substantially greater potential for cure than exists in cases in which discovery was delayed.

- Treatment of lesions detected by screening should offer improved outcomes as measured in cause-specific morbidity and mortality.

The following additional criteria are particularly relevant in the workplace:

- Employees (and their dependants, when involved in the programme) should be informed of the purpose, nature and potential results of the screening, and a formal “informed consent” should be obtained.

- The screening programme should be conducted with due consideration for the comfort, dignity and privacy of the individuals consenting to be screened and should involve minimal interference with working arrangements and production schedules.

- Screening results should be conveyed promptly and privately, with copies forwarded to personal physicians designated by the workers. Counselling by trained health professionals should be available to those seeking clarification of the screening report.

- The individuals screened should be informed of the possibility of false negatives and warned to seek medical evaluation of any signs or symptoms developing soon after the screening exercise.

- A prearranged referral network should be in place to which those with positive results who are not able or do not wish to consult their personal physicians may be referred.

- The costs of the necessary confirmatory examinations and the costs of treatment should be covered by health insurance or otherwise be affordable.

- A prearranged follow-up system should be in place to be sure that positive reports have been promptly confirmed and proper interventions arranged.

A further final criterion is of fundamental importance: the screening exercise should be conducted by properly skilled and accredited health professionals using state-of-the-art equipment and interpretation and analysis of the results should be of the highest possible quality and accuracy.

In 1989 the US Preventive Services Task Force, a panel of 20 experts from medicine and other related fields drawing upon hundreds of “advisors” and others from the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, assessed the effectiveness of some 169 preventive interventions. Its recommendations with respect to screening for cancer are summarized in table 1. Reflecting the Task Force’s somewhat conservative attitude and rigorously applied criteria, these recommendations may differ from those advanced by other groups.

Table 1. Screening for neoplastic diseases.

|

Types of cancer |

Recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force* |

|

Breast |

All women over age 40 should receive an annual clinical breast examination. Mammography every one to two years is recommended for all women beginning at age 50 and continuing until age 75 unless pathology has been detected. It may be prudent to begin mammography at an earlier age for women at high risk for breast cancer. Although the teaching of breast self-examination is not specifically recommended at this time, there is insufficient evidence to recommend any change in current breast self- examination practices (i.e., those who are now teaching it should continue the practice). |

|

Colorectal |

There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against fecal occult blood testing or sigmoidoscopy as effective screening tests for colorectal cancer in asymptomatic individuals. There are also insufficient grounds for discontinuing this form of screening where it is currently practiced or for withholding it from persons who request it. It may be clinically prudent to offer screening to persons aged 50 or older with known risk factors for colorectal cancer. |

|

Cervical |

Regular Papanicolaou (Pap) testing is recommended for all women who are or have been sexually active. Pap smears should begin with the onset of sexual activity and should be repeated every one to three years at the physician’s discretion. They may be discontinued at age 65 if previous smears have been consistently normal. |

|

Prostate |

There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine digital rectal examination as an effective screening test for prostate cancer in asymptomatic men. Transrectal ultrasound and serum tumor markers are not recommended for routine screening in asymptomatic men. |

|

Lung |

Screening asymptomatic persons for lung cancer by performing routine chest radiography or sputum cytology is not recommended. |

|

Skin |

Routine screening for skin cancer is recommended for persons at high risk. Clinicians should advise all patients with increased outdoor exposure to use sunscreen preparations and other measures to protect from ultraviolet rays. Currently there is no evidence for or against advising patients to perform skin self-examination. |

|

Testicular |

Periodic screening for testicular cancer by testicular examination is recommended for men with a history of cryptorchidism, orchiopexy, or testicular atrophy. There is no evidence of clinical benefit or harm to recommend for or against routine screening of other men for testicular cancer. Currently there is insufficient evidence for or against counseling patients to perform periodic self-examination of the testicles. |

|

Ovarian |

Screening of asymptomatic women for ovarian cancer is not recommended. It is prudent to examine the adnexa when performing gynecologic examinations for other reasons. |

|

Pancreatic |

Routine screening for pancreatic cancer in asymptomatic persons is not recommended. |

|

Oral |

Routine screening of asymptomatic persons for oral cancer by primary care clinicians is not recommended. All patients should be counseled to receive regular dental examinations, to discontinue the use of all forms of tobacco, and to limit consumption of alcohol. |

Source: Preventive Services Task Force 1989.

Screening for breast cancer

There is a general consensus among experts that screening with mammography combined with clinical breast examination every one to two years will save lives among women aged 50 to 69, reducing breast cancer deaths in this age group by up to 30%. Experts have not reached agreement, however, on the value of breast cancer screening with mammography for asymptomatic women aged 40 to 49. The NCI recommends that women in this age group should be screened every one to two years and that women at increased risk for breast cancer should seek medical advice about whether to begin screening before age 40.

The female population in most organizations may be too small to warrant the installation of mammography equipment onsite. Accordingly, most programs sponsored by employers or labor unions (or both) rely on contracts with providers who bring mobile units to the workplace or on providers in the community to whom participating female employees are referred either during working hours or on their own time. In making such arrangements, it is essential to be sure that the equipment meets standards for x-ray exposure and safety such as those promulgated by the American College of Radiology, and that the quality of the films and their interpretation is satisfactory. Further, it is imperative that a referral resource be prearranged for those women who will require a small needle aspiration or other confirmatory diagnostic procedures.

Screening for cervical cancer

Scientific evidence strongly suggests that regular screening with Pap tests will significantly decrease mortality from cervical cancer among women who are sexually active or who have reached the age of 18. Survival appears to be directly related to the stage of the disease at diagnosis. Early detection, using cervical cytology, is currently the only practical means of detecting cervical cancer in localized or premalignant stages. The risk of developing invasive cervical cancer is three to ten times greater in women who have never been screened than in those who have had Pap tests every two or three years.

Of particular relevance to the cost of workplace screening programs is the fact that cervical cytology smears can be obtained quite efficiently by properly trained nurses and do not require the involvement of a physician. Perhaps of even greater importance is the quality of the laboratory to which they are sent for interpretation.

Screening for colorectal cancer

It is generally agreed that early detection of precancerous colorectal polyps and cancers by periodic tests for fecal blood, as well as digital rectal and sigmoidoscopic examinations, and their timely removal, will reduce mortality from colorectal cancer among individuals aged 50 and over. The examination has been made less uncomfortable and more reliable with the replacement of the rigid sigmoidoscope by the longer, flexible fibreoptic instrument. There remains, however, some disagreement as to which tests should be relied upon and how often they should be applied.

Pros and cons of screening

There is general agreement about the value of cancer screening in individuals at risk because of family history, prior occurrence of cancer, or known exposure to potential carcinogens. But there appear to be justifiable concerns about the mass screening of healthy populations.

Advocates of mass screening for the detection of cancer are guided by the premise that early detection will be followed by improvements in morbidity and mortality. This has been demonstrated in some instances, but is not always the case. For example, although it is possible to detect lung cancer earlier by use of chest x rays and sputum cytology, this has not led to any improvement in treatment outcomes. Similarly, concern has been expressed that increasing the lead time for treatment of early prostatic cancers may not only be without benefit but may, in fact, be counterproductive in view of the longer period of well-being enjoyed by patients whose treatment is delayed.

In planning mass screening programs, consideration must also be given to the impact on the well-being and pocketbooks of patients with false positives. For example, in several series of cases, 3 to 8% of women with positive breast screenings had unnecessary biopsies for benign tumors; and in one experience with the fecal blood test for colorectal cancer, nearly one-third of those screened were referred for diagnostic colonoscopy, and most of them showed negative results.

It is clear that additional research is needed. To assess the efficacy of screening, the NCI has launched a major study, the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trials (PLCO) to evaluate early detection techniques for these four cancer sites. Enrolment for the PLCO began in November 1993, and will involve 148,000 men and women, aged 60 to 74 years, randomized to either the intervention or the control group. In the intervention group, men will be screened for lung, colorectal and prostatic cancer while women will be screened for lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer; those assigned to the control group will receive their usual medical care. For lung cancer, the value of an annual single-view chest x ray will be studied; for colorectal cancer, annual fibreoptic sigmoidoscopy will be performed; for prostate cancer, digital rectal examination and a blood test for PSA will be done; and for ovarian cancer, yearly physical and transvaginal ultrasound examinations will be supplemented by an annual blood test for the tumor marker known as CA-125. At the end of 16 years and the expenditure of US$ 87.8 million, it is hoped that solid data will be obtained about how screening may be used to obtain early diagnoses that may extend lives and reduce mortality.

Treatment and Continuing Care

Treatment and continuing care comprise efforts to enhance the quality of life for those in whom a cancer has taken hold and for those involved with them. Occupational health services and employee assistance programs sponsored by employers and unions can provide useful counsel and support to workers being treated for cancer or who have a dependant receiving treatment. This support can include explanations of what is going on and what to expect, information that is sometimes not provided by oncologists and surgeons; guidance in referrals for second opinions; and consultations and assistance with regard to access to centers of highly specialized care. Leaves of absence and modified work arrangements may make it possible for workers to remain productive while in treatment and to return to work earlier when a remission is achieved. In some workplaces, peer support groups have been formed to provide an exchange of experiences and mutual support for workers facing similar problems.

Conclusion

Programs for the prevention and detection of cancer can make a meaningful contribution to the well-being of the workers involved and their dependants and yield a significant return to the employers and labor unions that sponsor them. As with other preventive interventions, it is necessary that these programs be properly designed and carefully implemented and, since their benefits will accrue over many years, they should be continued on a steady basis.

Smoking Control Programmes at Merrill Lynch and Company, Inc.: A Case Study

In 1990, the US Government demonstrated strong support for workplace health promotion programs with the publication of Healthy People 2000, setting forth the National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for the Year 2000 (US Public Health Service 1991). One of these objectives calls for an increase in the percentage of worksites offering health promotion activities for their employees by the year 2000, “preferably as part of a comprehensive employee health promotion program” (Objective 8.6). Two objectives specifically include efforts to prohibit or severely restrict smoking at work by increasing the percentage of worksites with a formal smoking policy (Objective 3.11) and by enacting comprehensive state laws on clean indoor air (Objective 3.12).

In response to these objectives and employee interest, Merrill Lynch and Company, Inc. (hereafter called Merrill Lynch) launched the Wellness and You program for employees at headquarters locations in New York City and in the state of New Jersey. Merrill Lynch is a US-based, global financial management and advisory company, with a leadership position in businesses serving individuals as well as corporate and institutional clients. Merrill Lynch’s 42,000 employees in more than 30 countries provide services including securities underwriting, trading and brokering; investment banking; trading of foreign exchange, commodities and derivatives; banking and lending; and insurance sales and underwriting services. The employee population is diverse in terms of ethnicity, nationality, educational achievement and salary level. Nearly half of the employee population is headquartered in the New York City metropolitan area (includes part of New Jersey) and in two service centers in Florida and Colorado.

Merrill Lynch’s Wellness and You Program

The Wellness and You program is based in the Health Care Services Department and is managed by a doctorate-level health educator who reports to the medical director. The core wellness staff consists of the manager and a full-time assistant, and is supplemented by staff physicians, nurses and employee assistance counselors as well as outside consultants as needed.

In 1993, its initial year, over 9,000 employees representing approximately 25% of the workforce participated in a variety of Wellness and You activities, including the following:

- self-help and written information programmes, including the distribution of pamphlets on a diversity of health topics and a Merrill Lynch personal health guide designed to encourage employees to get the tests, immunizations, and guidance they need to stay healthy

- educational seminars and workshops on topics of broad interest such as smoking cessation, stress management, AIDS, and Lyme disease

- comprehensive screening programmes to identify employees at risk for cardiovascular disease, skin cancer, and breast cancer. These programmes were provided by outside contractors on company premises either in health services clinics or mobile van units

- ongoing programmes, including aerobic exercise in the company cafeteria and personal weight management classes in company conference rooms

- clinical care, including influenza immunizations, dermatology services, periodic health examinations and nutritional counselling in the employee health services clinics.

In 1994, the program expanded to include an onsite gynecology screening program comprising of Pap smears and pelvic and breast examinations; and a worldwide emergency medical assistance program to help American employees locate an English-speaking doctor anywhere in the world. In 1995, wellness programs will be extended to service offices in Florida and Colorado and will reach approximately half of the entire workforce. Most services are offered to employees free of charge or at nominal cost.

Smoking Control Programs at Merrill Lynch

Anti-smoking programs have gained a prominent place in the workplace wellness arena in recent years. In 1964, the US Surgeon General identified smoking as the single cause of the greater part of preventable disease and premature death (US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare 1964). Since then, research has demonstrated that the health risk from inhaling tobacco smoke is not limited to the smoker, but includes those who inhale second-hand smoke (US Department of Health and Human Services 1991). Consequently, many employers are taking steps to limit or curtail smoking by employees out of concern for employee health as well as their own “bottom lines”. At Merrill Lynch, Wellness and You includes three types of smoking cessation effort: (1) the distribution of written material, (2) smoking cessation programs, and (3) restrictive smoking policies.

Written materials

The wellness program maintains a wide selection of quality educational materials to provide information, assistance and encouragement to employees to improve their health. Self-help materials such as pamphlets and audiotapes designed to educate employees about the harmful effects of smoking and about the benefits of quitting are available in the health care clinic waiting rooms and through interoffice mail by request.

Written materials also are distributed at health fairs. Often these health fairs are sponsored in conjunction with national health initiatives so as to capitalize on existing media attention. For example, on the third Thursday of each November, the American Cancer Society sponsors the Great American Smokeout. This national campaign, designed to encourage smokers to give up cigarettes for 24 hours, is well publicized throughout the United States by television, radio and newspapers. The idea is that if smokers can prove to themselves that they can quit for the day, they might quit for good. In 1993’s Smokeout, 20.5% of smokers in the United States (9.4 million) stopped smoking or reduced the number of cigarettes they smoked for the day; 8 million of them reported continuing not to smoke or reducing their smoking one to ten days later.

Each year, members of Merrill Lynch’s medical department set up quit-smoking booths on the day of the Great American Smokeout at home office locations. Booths are stationed in high-traffic locations (lobbies and cafeterias) and provide literature, “survival kits” (containing chewing gum, cinnamon sticks, and self-help materials), and quit-smoking pledge cards to encourage smokers to quit smoking at least for the day.

Smoking cessation programs

Since no single smoking cessation program works for everyone, employees at Merrill Lynch are offered a variety of options. These include self-help written materials (“quit kits”), group programs, audiotapes, individual counseling and physician intervention. Interventions range from education and classic behavior modification to hypnosis, nicotine replacement therapy (e.g., “the patch” and nicotine chewing gum), or a combination. Most of these services are available to employees free of charge and some programs, such as group interventions, have been subsidized by the firm’s benefits department.

Non-smoking policies

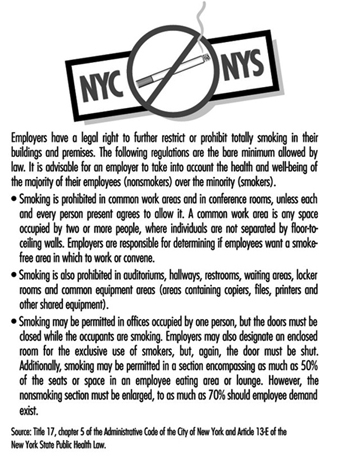

In addition to smoking cessation efforts aimed at individuals, smoking restrictions are becoming increasingly common in the workplace. Many jurisdictions in the United States, including the states of New York and New Jersey, have enacted strict workplace smoking laws that, for the most part, limit smoking to private offices. Smoking in common work areas and conference rooms is permitted, but only if each and every person present agrees to allow it. The statutes typically mandate that non-smokers’ preferences receive priority even to the point of banning smoking entirely. Figure 1 summarizes the city and state regulations applicable in New York City.

Figure 1. Summary of city and state restrictions on smoking in New York.

In many offices, Merrill Lynch has implemented smoking policies which extend beyond the legal requirements. Most headquarters cafeterias in New York City and in New Jersey have gone smoke-free. In addition, total smoking bans have been implemented in some office buildings in New Jersey and Florida, and in certain work areas in New York City.

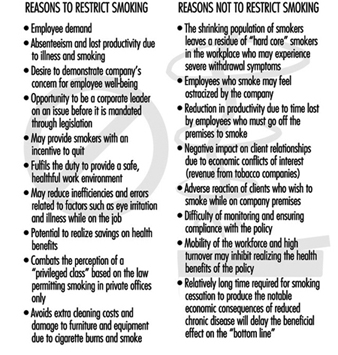

There seems to be little debate about the adverse health effects of tobacco exposure. However, other issues should be considered in developing a corporate smoking policy. Figure 2 outlines many of the reasons why a company may or may not elect to restrict smoking beyond the legal requirements.

Figure 2. Reasons for and against restricting smoking in the workplace.

Evaluation of Smoking Cessation Programs and Policies

Given the relative youth of the Wellness and You program, no formal evaluation has yet been conducted to determine the effect of these efforts on employee morale or smoking habits. However, some studies suggest that worksite smoking restrictions are favored by a majority of employees (Stave and Jackson 1991), result in decreased cigarette consumption (Brigham et al. 1994; Baile et al. 1991; Woodruff et al. 1993), and effectively increase smoking cessation rates (Sorensen et al. 1991).

Smoking Control in the Workplace

Introduction

Awareness of the adverse effects associated with cigarette smoking has increased since the 1960s when the first US Surgeon General’s report on this topic was released. Since that time, attitudes towards cigarette smoking have steadily grown towards the negative, with warning labels being required on cigarette packages and advertisements, bans on television advertising of cigarettes in some countries, the institution of non-smoking areas in some public places and the complete prohibition of smoking in others. Well-founded public health messages describing the dangers of tobacco products are increasingly widespread despite the tobacco industry’s attempts to deny that a problem exists. Many millions of dollars are spent each year by people trying to “kick the habit”. Books, tapes, group therapy, nicotine gum and skin patches, and even pocket computers have all been used with varying degrees of success in aiding those with nicotine addiction. Validation of the carcinogenic effects of passive, “second-hand” smoking has added impetus to the growing efforts to control the use of tobacco.

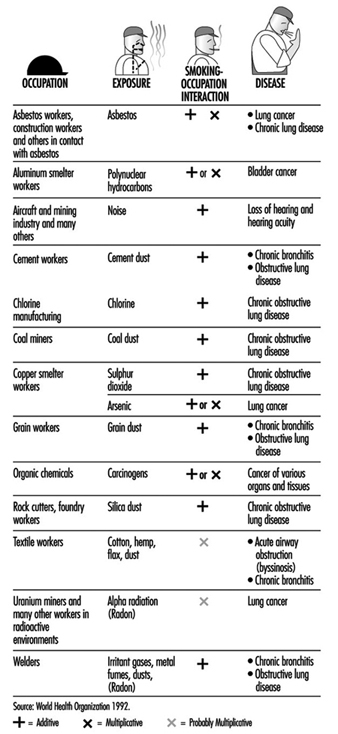

With this background, it is natural that smoking in the workplace should become a growing concern for employers and employees. On the most basic level, smoking represents a fire hazard. From a productivity standpoint, smoking represents either a distraction or an annoyance, depending on whether the employee is a smoker or a non-smoker. Smoking is a significant cause of morbidity in the workforce. It represents a drain in productivity in the form of the loss of work days due to illness, as well as a financial drain on an organization’s resources in terms of health-related costs. Furthermore, smoking has either an additive or multiplicative interaction with environmental hazards found in certain workplaces increasing significantly the risk of many occupational diseases (figure 1).

Figure 1. Examples of interactions between occupation and cigarette smoking causing disease.