Children categories

17. Disability and Work (10)

17. Disability and Work

Chapter Editors: Willi Momm and Robert Ransom

Table of Contents

Figures

Disability: Concepts and Definitions

Willi Momm and Otto Geiecker

Case Study: Legal Classification of Disabled People in France

Marie-Louise Cros-Courtial and Marc Vericel

Social Policy and Human Rights: Concepts of Disability

Carl Raskin

International Labour Standards and National Employment Legislation in Favour of Disabled Persons

Willi Momm and Masaaki Iuchi

Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment Support Services

Erwin Seyfried

Disability Management at the Workplace: Overview and Future Trends

Donald E. Shrey

Rehabilitation and Noise-induced Hearing Loss

Raymond Hétu

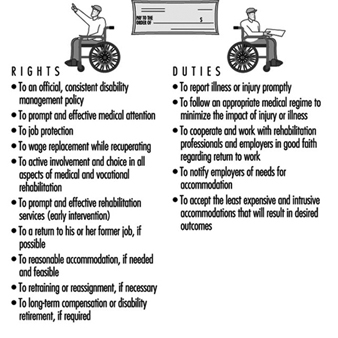

Rights and Duties: An Employer’s Perspective

Susan Scott-Parker

Case Study: Best Practices Examples

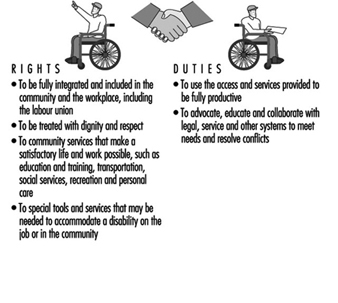

Rights and Duties: Workers’ Perspective

Angela Traiforos and Debra A. Perry

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

18. Education and Training (9)

18. Education and Training

Chapter Editor: Steven Hecker

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Introduction and Overview

Steven Hecker

Principles of Training

Gordon Atherley and Dilys Robertson

Worker Education and Training

Robin Baker and Nina Wallerstein

Case Studies

Evaluating Health and Safety Training: A Case Study in Chemical Workers Hazardous Waste Worker Education

Thomas H. McQuiston, Paula Coleman, Nina Wallerstein, A.C. Marcus, J.S. Morawetz, David W. Ortlieb and Steven Hecker

Environmental Education and Training: The State of Hazardous Materials Worker Education in the United States

Glenn Paulson, Michelle Madelien, Susan Sink and Steven Hecker

Worker Education and Environmental Improvement

Edward Cohen-Rosenthal

Safety and Health Training of Managers

John Rudge

Training of Health and Safety Professionals

Wai-On Phoon

A New Approach to Learning and Training:A Case Study by the ILO-FINNIDA African Safety and Health Project

Antero Vahapassi and Merri Weinger

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

19. Ethical Issues (10)

19. Ethical Issues

Chapter Editor: Georges H. Coppée

Table of Contents

Codes and Guidelines

Colin L. Soskolne

Responsible Science: Ethical Standards and Moral Behaviour in Occupational Health

Richard A. Lemen and Phillip W. Strine

Ethical Issues in Occupational Health and Safety Research

Paul W. Brandt-Rauf and Sherry I. Brandt-Rauf

Ethics in the Workplace: A Framework for Moral Judgement

Sheldon W. Samuels

Surveillance of the Working Environment

Lawrence D. Kornreich

Canons of Ethical Conduct and Interpretive Guidelines

Ethical Issues: Information and Confidentiality

Peter J. M. Westerholm

Ethics in Health Protection and Health Promotion

D. Wayne Corneil and Annalee Yassi

Case Study: Drugs and Alcohol in the Workplace - Ethical Considerations

Behrouz Shahandeh and Robert Husbands

International Code of Ethics for Occupational Health Professionals

International Commission on Occupational Health

20. Development, Technology and Trade (10)

20. Development, Technology and Trade

Chapter Editor: Jerry Jeyaratnam

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Occupational Health Trends in Development

Jerry Jeyaratnam

Industrialized Countries and Occupational Health and Safety

Toshiteru Okubo

Case Studies in Technological Change

Michael J. Wright

Small Enterprises and Occupational Health and Safety

Bill Glass

Transfer of Technology and Technological Choice

Joseph LaDou

Free-Trade Agreements

Howard Frumkin

Case Study: World Trade Organization

Product Stewardship and the Migration of Industrial Hazards

Barry Castleman

Economic Aspects of Occupational Health and Safety

Alan Maynard

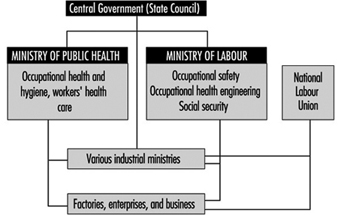

Case Study: Industrialization and Occupational Health Problems in China

Su Zhi

Tables

Click a link below to view table in the article context.

1. Small-scale enterprises

2. Information from foreign investors

3. Costs of work accidents & health (Britain)

4. Types of economic evaluation

5. Development of China’s township enterprises

6. Country HEPS & OHS coverages in China

7. Compliance rates of 6 hazards in worksites

8. Detectable rates of occupational diseases

9. Hazardous working & employers, China

10. OHS background in foreign-funded enterprises

11. Routine instruments for OHS, 1990, China

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

21. Labour Relations and Human Resources Management (12)

21. Labour Relations and Human Resources Management

Chapter Editor: Anne Trebilcock

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Labour Relations and Human Resources Management: An Overview

Anne Trebilcock

Rights of Association and Representation

Breen Creighton

Collective Bargaining and Safety and Health

Michael J. Wright

National Level Tripartite and Bipartite Cooperation on Health and Safety

Robert Husbands

Forms of Workers’ Participation

Muneto Ozaki and Anne Trebilcock

Case Study: Denmark: Worker Participation in Health and Safety

Anne Trebilcock

Consultation and Information on Health and Safety

Marco Biagi

Labour Relations Aspects of Training

Mel Doyle

Labour Relations Aspects of Labour Inspection

María Luz Vega Ruiz

Collective Disputes over Health and Safety Issues

Shauna L. Olney

Individual Disputes over Health and Safety Issues

Anne Trebilcock

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Practical activities-health & safety training

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

22. Resources: Information and OSH (5)

22. Resources: Information and OSH

Chapter Editor: Jukka Takala

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Information: A Precondition for Action

Jukka Takala

Finding and Using Information

P.K. Abeytunga, Emmert Clevenstine, Vivian Morgan and Sheila Pantry

Information Management

Gordon Atherley

Case study: Malaysian Information Service on Pesticide Toxicity

D.A. Razak, A.A. Latiff, M.I. A. Majid and R. Awang

Case Study: A Successful Information Experience in Thailand

Chaiyuth Chavalitnitikul

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Some core periodicals in occupational health & safety

2. Standard search form

3. Information required in occupational health & safety

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

23. Resources, Institutional, Structural and Legal (20)

23. Resources, Institutional, Structural and Legal

Chapter Editors: Rachael F. Taylor and Simon Pickvance

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Institutional, Structural and Legal Resources: Introduction

Simon Pickvance

Labour Inspection

Wolfgang von Richthofen

Civil and Criminal Liability in Relation to Occupational Safety and Health

Felice Morgenstern (adapted)

Occupational Health as a Human Right

Ilise Levy Feitshans

Community Level

Community-Based Organizations

Simon Pickvance

Right to Know: The Role of Community-Based Organizations

Carolyn Needleman

The COSH Movement and Right to Know

Joel Shufro

Regional and National Examples

Occupational Health and Safety: The European Union

Frank B. Wright

Legislation Guaranteeing Benefits for Workers in China

Su Zhi

Case Study: Exposure Standards in Russia

Nikolai F. Izmerov

International Governmental and Non-Governmental Organizations

International Cooperation in Occupational Health: The Role of International Organizations

Georges H. Coppée

The United Nations and Specialized Agencies

Contact Information for the United Nations Organization

International Labour Organization

Georg R. Kliesch

Case Study: ILO Conventions--Enforcement Procedures

Anne Trebilcock

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

Lawrence D. Eicher

International Social Security Association (ISSA)

Dick J. Meertens

Addresses of the ISSA International Sections

International Commission on Occupational Health (ICOH)

Jerry Jeyaratnam

International Association of Labour Inspection (IALI)

David Snowball

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Bases for Russian vs. American standards

2. ISO technical committees for OHS

3. Venues of triennial congresses since 1906

4. ICOH committees & working groups, 1996

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

24. Work and Workers (6)

24. Work and Workers

Chapter Editors: Jeanne Mager Stellman and Leon J. Warshaw

Table of Contents

Figures

Work and Workers

Freda L. Paltiel

Shifting Paradigms and Policies

Freda L. Paltiel

Health, Safety and Equity in the Workplace

Joan Bertin

Precarious Employment and Child Labour

Leon J. Warshaw

Transformations in Markets and Labour

Pat Armstrong

Globalizing Technologies and the Decimation/Transformation of Work

Heather Menzies

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

25. Worker's Compensation Systems (1)

25. Worker's Compensation Systems

Chapter Editor: Terence G. Ison

Table of Contents

Overview

Terence G. Ison

Part One: Workers' Compensation

Coverage

Organization, Administration and Adjudication

Eligibility for Benefits

Multiple Causes of Disability

Subsequent Consequential Disabilities

Compensable Losses

Multiple Disabilities

Objections to Claims

Employer Misconduct

Medical Aid

Money Payments

Rehabilitation and Care

Obligations to Continue the Employment

Finance

Vicarious Liability

Health and Safety

Claims against Third Parties

Social Insurance and Social Security

Part Two: Other Systems

Accident Compensation

Sick Pay

Disability Insurance

Employers’ Liability

26. Topics in Workers' Compensation Systems (6)

26. Topics in Workers' Compensation Systems

Chapter Editors: Paule Rey and Michel Lesage

Table of Contents

Tables

Work-Related Diseases and Occupational Diseases: The ILO International List

Michel Lesage

Workers’ Compensation: Trends and Perspectives

Paule Rey

Prevention, Rehabilitation and Compensation in the German Accident Insurance System

Dieter Greiner and Andreas Kranig

Employment Injuries Insurance and Compensation in Israel

Haim Chayon

Workers’ Accident Compensation in Japan

Kazutaka Kogi and Haruko Suzuki

Country Case Study: Sweden

Peter Westerholm

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Proposed ILO list of occupational diseases

2. Recipients of benefits in Israel

3. Premium rates in Japan

4. Enterprises, workers & costs in Japan

5. Payment of benefits by industry in Japan

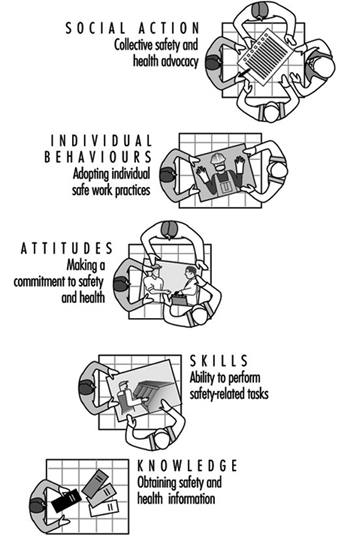

A New Approach to Learning and Training: A Case Study by the ILO-FINNIDA African Safety and Health Project

Abuya: What’s the matter? You look worn out.

Mwangi: I am worn out—and disgusted. I was up half the night getting ready for this lecture I just gave and I don’t think it went very well. I couldn’t get anything out of them—no questions, no enthusiasm. For all I know, they didn’t understand a word I said.

Kariuki: I know what you mean. Last week I was having a terrible time trying to explain chemical safety in Swahili.

Abuya: I don’t think it’s the language. You were probably just talking over their heads. How much technical information do these workers really need to know anyway?

Kariuki: Enough to protect themselves. If we can’t get the point across, we’re just wasting our time. Mwangi, why didn’t you try asking them something or tell a story?

Mwangi: I couldn’t figure out what to do. I know there has to be a better way, but I was never trained in how to do these lectures right.

Abuya: Why all the fuss? Just forget about it! With all the inspections we have to do, who’s got time to worry about training?

The above discussion in an African factory inspectorate, which could take place anywhere, highlights a real problem: how to get the message through in a training session. Using a real problem as a discussion starter (or trigger) is an excellent training technique to identify potential obstacles to training, their causes and potential solutions. We have used this discussion as a role play in our Training of Trainers’ workshops in Kenya and Ethiopia.

The ILO-FINNIDA African Safety and Health Project is part of the ILO’s technical cooperation activities aimed to improve occupational safety and health training and information services in 21 African countries where English is commonly spoken. It is sponsored by FINNIDA, the Finnish International Development Agency. The Project took place from 1991 to 1994 with a budget of US$5 million. One of the main concerns in the implementation of the Project was to determine the most appropriate training approach by which to facilitate high quality learning. In the following case study we will describe the practical implementation of the training approach, the Training the Trainers’ (TOT) course (Weinger 1993).

Development of a New Training Approach

In the past, the training approach in most African factory inspectorates, and also in many technical cooperation projects of the ILO, has been based on randomly selected, isolated topics of occupational safety and health (OSH) which were presented mainly by using lecturing methods. The African Safety and Health Project conducted the first pilot course in TOT in 1992 for 16 participating countries. This course was implemented in two parts, the first part dealing with basic principles of adult education (how people learn, how to establish learning objectives and select teaching contents, how to design the curriculum and select instructional methods and learning activities and how to improve personal teaching skills) and the second part with practical training in OSH based on individual assignments which each participant completed during a four month’s time period following the first part of the course.

The main characteristics of this new approach are participation and action orientation. Our training does not reflect the traditional model of classroom learning where participants are passive recipients of information and the lecture is the dominant instructional method. In addition to its action orientation and participatory training methods, this approach is based on the latest research in modern adult education and takes a cognitive and activity-theoretical view of learning and teaching (Engeström 1994).

On the basis of the experience gained during the pilot course, which was extremely successful, a set of detailed course material was prepared, call the Training of Trainers Package, which consists of two parts, a trainer’s manual and a supply of participants’ handout matter. This package was used as a guideline during planning sessions, attended by from 20 to 25 factory inspectors over a period of ten days, and concerned with establishing national TOT courses in Africa. By the spring of 1994, national TOT courses had been implemented in two African countries, Kenya and Ethiopia.

High Quality Learning

There are four key components of high quality learning.

Motivation for learning. Motivation occurs when participants see the “use-value” of what they are learning. It is stimulated when they can perceive the gap that separates what they know and what they need to know to solve a problem.

Organization of subject matter. The content of learning is too commonly thought of as separate facts stored in the brain like items in boxes on a shelf. In reality, people construct models, or mental pictures, of the world while learning. In promoting cognitive learning, teachers try to organize facts into models for better learning and include explanatory principles or concepts (the “but whys” behind a fact or skill).

Advancing through steps in the learning process. In the learning process, the participant is like an investigator looking for a model by which to understand the subject matter. With the help of the teacher, the participant forms this model, practices using it and evaluates its usefulness. This process can be divided into the following six steps:

- motivation

- orientation

- integrating new knowledge (internalization)

- application

- programme critique

- participant evaluation.

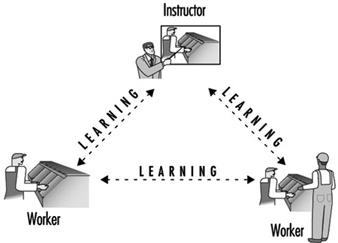

Social interaction. The social interaction between participants in a training session is an essential component of learning. In group activities, participants learn from one another.

Planning training for high quality learning

The kind of education aimed at particular skills and competencies is called training. The goal of training is to facilitate high quality learning and it is a process that takes place in a series of steps. It requires careful planning at each stage and each step is equally important. There are many ways of breaking the training into components but from the point of view of the cognitive conception of learning, the task of planning a training course can be analysed into six steps.

Step 1: Conduct a needs assessment (know your audience).

Step 2: Formulate learning objectives.

Step 3: Develop an orientation basis or “road map” for the course.

Step 4: Develop the curriculum, establishing its contents and associated training methods and using a chart to outline your curriculum.

Step 5: Teach the course.

Step 6: Evaluate the course and follow up on the evaluation.

Practical Implementation of National TOT Courses

Based on the above-mentioned training approach and experience from the first pilot course, two national TOT courses were implemented in Africa, the one in Kenya in 1993 and the other in Ethiopia in 1994.

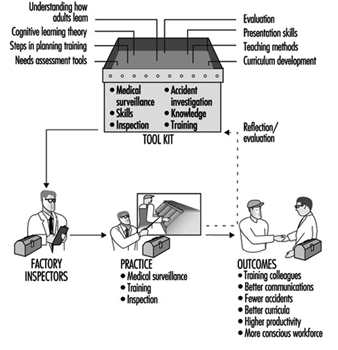

Training needs were based on the work activity of factory inspectors and were determined by means of a pre-workshop questionnaire and a discussion with the course participants about their everyday work and about the kinds of skills and competencies necessary to carry it out (see figure 1). The course has thus been designed primarily for factory inspectors (in our national TOT courses, usually 20 to 25 inspectors participated), but it could be extended to other personnel who may need to carry out safety and health training, such as shop stewards, foremen, and safety and health officers.

Figure 1. Orientation basis for the factory inspector's work activity.

A compilation of course objectives for the national TOT course was assembled step by step in cooperation with the participants, and is given immediately below.

Objectives of the national TOT course

The aims of the training of trainers (TOT) course are as follows:

- Increase participants’ understanding of the changing role and tasks of factory inspectors from immediate enforcement to long-term advisory service, including training and consultation.

- Increase participants’ understanding of the basic principles of high quality learning and instruction.

- Increase participants’ understanding of the variety of skills involved in planning training programmes: identification of training needs, formulation of learning objectives, development of training curricula and materials, selection of appropriate teaching methods, effective presentation and programme evaluation.

- Enhance participants’ skills in effective communication for application during inspections and consultation, as well as in formal training sessions.

- Facilitate the development of short and long-term training plans in which new instructional practices will be implemented.

Course contents

The key subject areas or curriculum units that guided the implementation of the TOT course in Ethiopia are outlined in figure 2. This outline may also serve as an orientation basis for the whole TOT course.

Figure 2. The key subject areas of the TOT course.

Determining training methods

The external aspect of the teaching method is immediately observable when you step into a classroom. You might observe a lecture, a discussion, group or individual work. However, what you do not see is the most essential aspect of teaching: the kind of mental work being accomplished by the student at any given moment. This is called the internal aspect of the teaching method.

Teaching methods can be divided into three main groups:

- Instructional presentation: participant presentations, lectures, demonstrations, audio-visual presentations

- Independent assignment: tests or exams, small group activities, assigned reading, use of self-guided learning materials, role plays

- Cooperative instruction

Most of the above methods were used in our TOT courses. However, the method one selects depends on the learning objectives one wants to achieve. Each method or learning activity should have a function. These instructional functions, which are the activities of a teacher, correspond with the steps in the learning process described above and can help guide your selection of methods. There follows a list of the nine instructional functions:

- preparation

- motivation

- orientation

- transmitting new knowledge

- consolidating what has been taught

- practising (development of knowledge into skills)

- application (solving new problems with the help of new knowledge)

- programme critique

- participant evaluation.

Planning the curriculum: Charting your course

One of the functions of curriculum or course plan is to assist in guiding and monitoring the teaching and learning process. The curriculum can be divided into two parts, the general and the specific.

The general curriculum gives an overall picture of the course: its goals, objectives, contents, participants and guidelines for their selection, the teaching approach (how the course will be conducted) and the organizational arrangements, such as pre-course tasks. This general curriculum would usually be your course description and a draft programme or list of topics.

A specific curriculum provides detailed information on what one will teach and how one plans to teach it. A written curriculum prepared in chart form will serve as a good outline for designing a curriculum specific enough to serve as a guide in the implementation of the training. Such a chart includes the following categories:

Time: the estimated time needed for each learning activity

Curriculum Units: primary subject areas

Topics: themes within each curriculum unit

Instructional function: the function of each learning activity in helping to achieve your learning objectives

Activities: the steps for conducting each learning activity

Materials: the resources and materials needed for each activity

Instructor: the trainer responsible for each activity (when there are several trainers)

To design the curriculum with the aid of the chart format, follow the steps outlined below. Completed charts are illustrated in connection with a completed curriculum in Weinger 1993.

- Specify the primary subject areas of the course (curriculum units) which are based on your objectives and general orientation basis.

- List the topics you will cover in each of those areas.

- Plan to include as many instructional functions as possible in each subject area in order to advance through all the steps of the learning process.

- Choose methods which fulfil each function and estimate the amount of time required. Record the time, topic and function on the chart.

- In the activities column, provide guidelines for the instructor on how to conduct the activity. Entries can also include main points to be covered in this session. This column should offer a clear picture of exactly what will occur in the course during this time period.

- List the materials, such as worksheets, handouts or equipment required for each activity.

- Make sure to include appropriate breaks when designing a cycle of activities.

Evaluating the course and follow-up

The last step in the training process is evaluation and follow-up. Unfortunately, it is a step that is often forgotten, ignored and, sometimes, avoided. Evaluation, or the determination of the degree to which course objectives were met, is an essential component of training. This should include both programme critique (by the course administrators) and participant evaluation.

Participants should have an opportunity to evaluate the external factors of teaching: the instructor’s presentation skills, techniques used, facilities and course organization. The most common evaluation tools are post-course questionnaires and pre- and post-tests.

Follow-up is a necessary support activity in the training process. Follow-up activities should be designed to help the participants apply and transfer what they have learned to their jobs. Examples of follow-up activities for our TOT courses include:

- action plans and projects

- formal follow-up sessions or workshops

Selection of trainers

Trainers were selected who were familiar with the cognitive learning approach and had good communication skills. During the pilot course in 1992 we used international experts who had been involved in development of this learning approach during the 1980s in Finland. In the national courses we have had a mixture of experts: one international expert, one or two regional experts who had participated in the first pilot course and two to three national resource persons who either had responsibility for training in their own countries or who had participated earlier in this training approach. Whenever it was possible, project personnel also participated.

Discussion and Summary

Factory training needs assessment

The factory visit and subsequent practice teaching are a highlight of the workshop. This training activity was used for workplace training needs assessment (curriculum unit VI A, figure 1). The recommendation here would be to complete the background on theory and methods prior to the visit. In Ethiopia, we scheduled the visit prior to addressing ourselves to the question of teaching methods. While two factories were looked at, we could have extended the time for needs assessment by eliminating one of the factory visits. Thus, visiting groups will visit and focus on only that factory where they will be actually training.

The risk mapping component of the workshop (this is also part of curriculum unit VI A) was even more successful in Ethiopia than in Kenya. The risk maps were incorporated in the practice teaching in the factories and were highly motivating for the workers. In future workshops, we would stress that specific hazards be highlighted wherever they occur, rather than, for example, using a single green symbol to represent any of a variety of physical hazards. In this way, the extent of a particular type of hazard is more clearly reflected.

Training methods

The instructional methods focused on audio-visual techniques and the use of discussion starters. Both were quite successful. In a useful addition to the session on transparencies, the participants were asked to work in groups to develop a transparency of their own on the contents of an assigned article.

Flip charts and brainstorming were new teaching methods for participants. In fact, a flip chart was developed especially for the workshop. In addition to being an excellent training aid, the use of flip charts and “magic markers” is a very inexpensive and practical substitute for the overhead projector, which is unavailable to most inspectors in the developing countries.

Videotaped microteaching

“Microteaching”, or instruction in the classroom focusing on particular local problems, made use of videotape and subsequent critique by fellow participants and resource people, and was very successful. In addition to enhancing the working of external teaching methods, the taping was a good opportunity for comment on areas for improvement in content prior to the factory teaching.

A common error, however, was the failure to link discussion starters and brainstorm activities with the content or message of an activity. The method was perfunctorily executed, and its effect ignored. Other common errors were the use of excessively technical terminology and the failure to make the training relevant to the audience’s needs by using specific workplace examples. But the later presentations in the factory were designed to clearly reflect the criticisms that participants had received the day before.

Practice teaching in the factory

In their evaluation of the practice teaching sessions in the factory, participants were extremely impressed with the use of a variety of teaching methods, including audiovisuals, posters that they developed, flip charts, brainstorming, role plays, “buzz groups” and so on. Most groups also made use of an evaluation questionnaire, a new experience for them. Of particular note was their success in engaging their audiences, after having relied solely on the lecture method in the past. Common areas for improvement were time management and the use of overly technical terms and explanations. In the future, the resource persons should also try to ensure that all groups include the application and evaluation steps in the learning process.

Course planning as a training experience

During these two courses it was possible to observe significant changes in the participants’ understanding of the six steps in high quality learning.

In the last course a section on writing objectives, where each participant writes a series of instructional objectives, was added into the programme. Most participants had never written training objectives and this activity was extremely useful.

As for the use of the curriculum chart in planning, we have seen definite progress among all participants and mastery by some. This area could definitely benefit from more time. In future workshops, we would add an activity where participants use the chart to follow one topic through the learning process, using all of the instructional functions. There is still a tendency to pack the training with content material (topics) and to intersperse, without due consideration of their relevance, the various instructional functions throughout a series of topics. It is also necessary that trainers emphasize those activities that are chosen to accomplish the application step in the learning process, and that they acquire more practice in developing learners’ tasks. Application is a new concept for most and difficult to incorporate in the instructional process.

Finally the use of the term curriculum unit was difficult and sometimes confusing. The simple identification and ordering of relevant topic areas is an adequate beginning. It was also obvious that many other concepts of the cognitive learning approach were difficult, such as the concepts of orientation basis, external and internal factors in learning and teaching, instructional functions and some others.

In summary, we would add more time to the theory and curriculum development sections, as outlined above, and to the planning of future curriculum, which affords the opportunity of observing individual ability to apply the theory.

Conclusion

The ILO-FINNIDA African Safety and Health Project has undertaken a particularly challenging and demanding task: to change our ideas and old practices about learning and training. The problem with talking about learning is that learning has lost its central meaning in contemporary usage. Learning has come to be synonymous with taking in information. However, taking in information is only distantly related to real learning. Through real learning we re-create ourselves. Through real learning we become able to do something we were never able to do before (Senge 1990). This is the message in our Project’s new approach on learning and training.

Rehabilitation and Noise - Induced Hearing Loss

Raymond Hétu

* This article was written by Dr. Hétu shortly before his untimely death. His colleagues and friends consider it one memoriam to him.

Although this article deals with disability due to noise-exposure and hearing loss, it is included here because it also contains fundamental principles applicable to rehabilitation from disabilities arising from other hazardous exposures.

Psychosocial Aspects of Occupationally Induced Hearing Loss

Like all human experience, hearing loss caused by exposure to workplace noise is given meaning—it is qualitatively experienced and evaluated—by those whom it affects and by their social group. This meaning can, however, be a powerful obstacle to the rehabilitation of individuals suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss (Hétu and Getty 1991b). The chief reasons, as discussed below, are that the victims of hearing loss experience perceptual barriers related to the signs and effects of their deficiency and that the manifestation of overt signs of hearing loss is highly stigmatizing.

Communication problems due to the distorted perception of hearing

Difficulties in hearing and communication resulting from occupationally induced hearing loss are usually attributed to other causes, for example unfavourable conditions for hearing or communication or a lack of attention or interest. This erroneous attribution is observed in both the affected individual and among his or her associates and has multiple, although converging, causes.

- Internal ear injuries are invisible, and victims of this type of injury do not see themselves as physically injured by noise.

- Hearing loss per se progresses very insidiously. The virtually daily auditory fatigue due to workplace noise suffered by exposed workers makes the timely detection of irreversible alterations in hearing function a matter of the greatest difficulty. Individuals exposed to noise are never aware of tangible deteriorations of hearing capacity. In fact, in most workers exposed daily to harmful levels of noise, the increase in the auditory threshold is of the order of one decibel per year of exposure (Hétu, Tran Quoc and Duguay 1990). When hearing loss is symmetric and progressive, the victim has no internal reference against which to judge the induced hearing deficit. As a result of this insidious evolution of hearing loss, individuals undergo a very progressive change of habits, avoiding situations which place them at a disadvantage—without however explicitly associating this change with their hearing problems.

- The signs of hearing loss are very ambiguous and usually take the form of a loss of frequency discrimination, that is, a diminished ability to discriminate between two or more simultaneous acoustic signals, with the more intense signal masking the other(s). Concretely, this takes the form of varying degrees of difficulty in following conversations where reverberation is high or where background noise due to other conversations, televisions, fans, vehicle motors, and so forth, is present. In other words, the hearing capacity of individuals suffering from impaired frequency discrimination is a direct function of the ambient conditions at any given moment. Those with whom the victim comes into daily contact experience this variation in hearing capacity as inconsistent behaviour on the part of the affected individual and reproach him or her in terms like, “You can understand well enough when it suits your purpose”. The affected individual, on the other hand, considers his or her hearing and communication problems to be the result of background noise, inadequate articulation by those addressing him or her, or a lack of attention on their part. In this way, the most characteristic sign of noise-induced hearing loss fails to be recognized for what it is.

- The effects of hearing loss are usually experienced outside of the workplace, within the confines of family life. Consequently, problems are not associated with occupational exposure to noise and are not discussed with work colleagues suffering similar difficulties.

- Acknowledgement of hearing problems is usually triggered by reproaches from the victim’s family and social circles (Hétu, Jones and Getty 1993). Affected individuals violate certain implicit social norms, for example by speaking too loudly, frequently asking others to repeat themselves and turning the volume of televisions or radios up too high. These behaviours elicit the spontaneous—and usually derogatory—question, “Are you deaf?” from those around. The defensive behaviours that this triggers do not favour the acknowledgement of partial deafness.

As a result of the convergence of these five factors, individuals suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss do not recognize the effects of their affliction on their daily lives until the loss is well advanced. Typically, this occurs when they find themselves frequently asking people to repeat themselves (Hétu, Lalonde and Getty 1987). Even at this point, however, victims of occupationally induced hearing loss are very unwilling to acknowledge their hearing loss on account of the stigma associated with deafness.

Stigmatization of the signs of deafness

The reproaches elicited by the signs of hearing loss are a reflection of the extremely negative value construct typically associated with deafness. Workers exhibiting signs of deafness risk being perceived as abnormal, incapable, prematurely old, or handicapped—in short, they risk becoming socially marginalized in the workplace (Hétu, Getty and Waridel 1994). These workers’ negative self-image thus intensifies as their hearing loss progresses. They are obviously reluctant to embrace this image, and by extension, to acknowledge the signs of hearing loss. This leads them to attribute their hearing and communication problems to other factors and to become passive in the face of these factors.

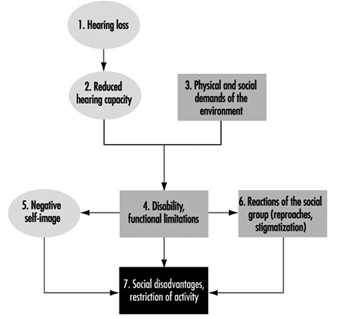

The combined effect of the stigma of deafness and the distorted perception of the signs and effects of hearing loss on rehabilitation is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for incapacity from handicap

When hearing problems progress to the point that it is no longer possible to deny or minimize them, individuals attempt to hide the problem. This invariably leads to social withdrawal on the part of the worker and exclusion on the part of the worker’s social group, which ascribes the withdrawal to a lack of interest in communicating rather than to hearing loss. The result of these two reactions is that the affected individual is not offered help or informed of coping strategies. Workers’ dissimulation of their problems may be so successful that family members and colleagues may not even realize the offensive nature of their jokes elicited by the signs of deafness. This situation only exacerbates the stigmatization and its resultant negative effects. As Figure 1 illustrates, the distorted perceptions of the signs and effects of hearing loss and the stigmatization which results from these perceptions are barriers to the resolution of hearing problems. Because affected individuals are already stigmatized, they initially refuse to use hearing aids, which unmistakably advertise deafness and so promote further stigmatization.

The model presented in Figure 1 accounts for the fact that most people suffering occupationally induced hearing loss do not consult audiology clinics, do not request modification of their workstations and do not negotiate enabling strategies with their families and social groups. In other words, they endure their problems passively and avoid situations which advertise their auditory deficit.

Conceptual Framework of Rehabilitation

For rehabilitation to be effective, it is necessary to overcome the obstacles outlined above. Rehabilitative interventions should therefore not be limited to attempts to restore hearing capacity, but should also address issues related to the way hearing problems are perceived by affected individuals and their associates. Because stigmatization of deafness is the greatest obstacle to rehabilitation (Hétu and Getty 1991b; Hétu, Getty and Waridel 1994), it should be the primary focus of any intervention. Effective interventions should therefore include both stigmatized workers and their circles of family, friends, colleagues and others with whom they come into contact, since it is they who stigmatize them and who, out of ignorance, impose impossible expectations on them. Concretely, it is necessary to create an environment which allows affected individuals to break out of their cycle of passivity and isolation and actively seek out solutions to their hearing problems. This must be accompanied by a sensitization of the entourage to the specific needs of affected individuals. This process is grounded in the ecological approach to incapacity and handicap illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2. Model of restrictions due to hearing loss

In the ecological model, hearing loss is experienced as an incompatibility between an individual’s residual capacity and the physical and social demands of his or her environment. For example, workers suffering from a loss of frequency discrimination associated with noise-induced hearing loss will have difficulty detecting acoustic alarms in noisy workplaces. If the alarms required at workstations cannot be adjusted to levels significantly louder than those appropriate for people with normal hearing, the workers will be placed in a handicapped position (Hétu 1994b). As a result of this handicap, workers may be at the obvious disadvantage of being deprived of a means to protect themselves. Yet, simply acknowledging hearing loss puts the worker at risk of being considered “abnormal” by his or her colleagues, and when labelled disabled he or she will fear being seen as incompetent by colleagues or superiors. In either case, workers will attempt to hide their handicap or deny the existence of any problems, placing themselves at a functional disadvantage at work.

As figure 2 illustrates, disability is a complex state of affairs with several interrelated restrictions. In such a network of relationships, prevention or minimization of disadvantages or restrictions of activity require simultaneous interventions on many fronts. For example, hearing aids, while partially restoring hearing capacity (component 2), do not prevent either the development of a negative self-image or stigmatization by the worker’s entourage (components 5 and 6), both of which are responsible for isolation and avoidance of communication (component 7). Further, auditory supplementation is incapable of completely restoring hearing capacity; this is particularly true with regard to frequency discrimination. Amplification may improve the perception of acoustic alarms and of conversations but is incapable of improving the resolution of competing signals required for the detection of warning signals in the presence of significant background noise. The prevention of disability-related restrictions therefore necessitates the modification of the social and physical demands of the workplace (component 3). It should be superfluous to note that although interventions designed to modify perceptions (components 5 and 6) are essential and do prevent disability from arising, they do not palliate the immediate consequences of these situations.

Situation-specific Approaches to Rehabilitation

The application of the model presented in Figure 2 will vary depending on the specific circumstances encountered. According to surveys and qualitative studies (Hétu and Getty 1991b; Hétu, Jones and Getty 1993; Hétu, Lalonde and Getty 1987; Hétu, Getty and Waridel 1994; Hétu 1994b), the effects of disability suffered by victims of occupationally induced hearing loss are particularly felt: (1) at the workplace; (2) at the level of social activities; and (3) at the family level. Specific intervention approaches have been proposed for each of these situations.

The workplace

In industrial workplaces, it is possible to identify the following four restrictions or disadvantages requiring specific interventions:

- accident hazards related to the failure to detect warning signals

- efforts, stress and anxiety resulting from hearing and com-munication problems

- obstacles to social integration

- obstacles to professional advancement.

Accident hazards

Acoustic warning alarms are frequently used in industrial workplaces. Occupationally induced hearing loss may considerably diminish workers’ ability to detect, recognize or locate such alarms, particularly in noisy workplaces with high levels of reverberation. The loss of frequency discrimination which inevitably accompanies hearing loss may in fact be so pronounced as to require warning alarms to be 30 to 40db louder than background levels to be heard and recognized by affected individuals (Hétu 1994b); for individuals with normal hearing, the corresponding value is approximately 12 to 15db. Currently, it is rare that warning alarms are adjusted to compensate for background noise levels, workers’ hearing capacity or the use of hearing protection equipment. This puts affected workers at a serious disadvantage, especially as far as their safety is concerned.

Given these constraints, rehabilitation must be based on a rigorous analysis of the compatibility of auditory perception requirements with residual auditory capacities of affected workers. A clinical examination capable of characterizing an individual’s ability to detect acoustic signals in the presence of background noise, such as the DetectsoundTM software package (Tran Quoc, Hétu and Laroche 1992), has been developed, and is available to determine the characteristics of acoustic signals compatible with workers’ hearing capacity. These devices simulate normal or impaired auditory detection and take into account the characteristics of the noise at the workstation and the effect of hearing protection equipment. Of course, any intervention aimed at reducing the noise level will facilitate the detection of acoustic alarms. It is nevertheless necessary to adjust the alarms’ level as a function of the residual hearing capacity of affected workers.

In some cases of relatively severe hearing loss, it may be necessary to resort to other types of warning, or to supplement hearing capacity. For example, it is possible to transmit warning alarms over FM bandwidths and receive them with a portable unit connected directly to a hearing aid. This arrangement is very effective as long as: (1) the tip of the hearing aid fits perfectly (in order to attenuate background noise); and (2) the response curve of the hearing aid is adjusted to compensate for the masking effect of background noise attenuated by the hearing aid tip and the worker’s hearing capacity (Hétu, Tran Quoc and Tougas 1993). The hearing aid may be adjusted to integrate the effects of the full spectrum of background noise, the attenuation produced by the hearing aid’s tip, and the worker’s hearing threshold. Optimal results will be obtained if the frequency discrimination of the worker is also measured. The hearing aid-FM receptor may also be used to facilitate verbal communication with work colleagues when this is essential for worker safety.

In some cases, the workstation itself must be redesigned in order to ensure worker safety.

Hearing and communication problems

Acoustic warning alarms are usually used to inform workers of the state of a production process and as a means of inter operator communication. In workplaces where such alarms are used, individuals with hearing loss must rely upon other sources of information to perform their work. These may involve intense visual surveillance and discreet help offered by work colleagues. Verbal communication, whether over the telephone, in committee meetings or with superiors in noisy workshops, requires great effort on the part of affected individuals and is also highly problematic for affected individuals in industrial workplaces. Because these individuals feel the need to hide their hearing problems, they are also plagued by the fear of being unable to cope with a situation or of committing costly errors. Often, this may cause extremely high anxiety (Hétu and Getty 1993).

Under these circumstances, rehabilitation must first focus on eliciting explicit acknowledgement by the company and its representatives of the fact that some of their workers suffer from hearing difficulties caused by noise exposure. The legitimization of these difficulties helps affected individuals to communicate about them and to avail themselves of appropriate palliative means. However, these means must in fact be available. In this regard, it is astonishing to note that telephone receivers in the workplace are rarely equipped with amplifiers designed for individuals suffering from hearing loss and that conference rooms are not equipped with appropriate systems (FM or infrared transmitters and receptors, for example). Finally, a campaign to increase awareness of the needs of individuals suffering from hearing loss should be undertaken. By publicizing strategies which facilitate communication with affected individuals, communication-related stress will be greatly reduced. These strategies consist of the following phases:

- approaching the affected individual and facing him or her

- articulating without exaggeration

- repeating misunderstood phrases, using different words

- keeping as far away from sources of noise as possible

Clearly, any control measures that lead to lower noise and reverberation levels in the workplace also facilitate communication with individuals suffering from hearing loss.

Obstacles to social integration

Noise and reverberation in the workplace render communication so difficult that it is often limited to the strict minimum required by the tasks to be accomplished. Informal communication, a very important determinant of the quality of working life, is thus greatly impaired (Hétu 1994a). For individuals suffering from hearing loss, the situation is extremely difficult. Workers suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss are isolated from their work colleagues, not only at their workstation but even during breaks and meals. This is a clear example of the convergence of excessive work requirements and the fear of ridicule suffered by affected individuals.

The solutions to this problem lie in the implementation of the measures already described, such as the lowering of overall noise levels, particularly in rest areas, and the sensitization of work colleagues to the needs of affected individuals. Again, recognition by the employer of affected individuals’ specific needs itself constitutes a form of psychosocial support capable of limiting the stigma associated with hearing problems.

Obstacles to professional advancement

One of the reasons individuals suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss take such pains to hide their problem is the explicit fear of being disadvantaged professionally (Hétu and Getty 1993): some workers even fear losing their jobs should they reveal their hearing loss. The immediate consequence of this is a self-restriction with regard to professional advancement, for example, failure to apply for a promotion to shift supervisor, supervisor or foreman. This is also true of professional mobility outside the company, with experienced workers failing to take advantage of their accumulated skills since they feel that pre-employment audiometric examinations would block their access to better jobs. Self-restriction is not the only obstacle to professional advancement caused by hearing loss. Workers suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss have in fact reported instances of employer bias when positions requiring frequent verbal communication have become available.

As with the other aspects of disability already described, explicit acknowledgement of affected workers’ specific needs by employers greatly eliminates obstacles to professional advancement. From the standpoint of human rights (Hétu and Getty 1993), affected individuals have the same right to be considered for advancement as do other workers, and appropriate workplace modifications can facilitate their access to higher-level jobs.

In summary, the prevention of disability in the workplace requires sensitization of employers and work colleagues to the specific needs of individuals suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss. This can be accomplished by information campaigns on the signs and effects of noise-induced hearing loss aimed at dissipating the view of hearing loss as an improbable abnormality of little import. The use of technological aids is possible only if the need to use them has been legitimized in the workplace by colleagues, superiors and affected individuals themselves.

Social activities

Individuals suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss are at a disadvantage in any non-ideal hearing situation, for instance, in the presence of background noise, in situations requiring communication at a distance, in environments where reverberation is high and on the telephone. In practice, this greatly curtails their social life by limiting their access to cultural activities and public services, thus hindering their social integration (Hétu and Getty 1991b).

Access to cultural activities and public services

In accordance with the model in Figure 2, restrictions related to cultural activities involve four components (components 2, 3, 5 and 6) and their elimination relies on multiple interventions. Thus concert halls, auditoriums and places of worship can be made accessible to persons suffering from hearing loss by equipping them with appropriate listening systems, such as FM or infrared transmission systems (component 3) and by informing those responsible for these institutions of the needs of affected individuals (component 6). However, affected individuals will request hearing equipment only if they are aware of its availability, know how to use it (component 2) and have received the necessary psychosocial support to recognize and communicate their need for such equipment (component 5).

Effective communication, training and psychosocial support channels for hearing-impaired workers have been developed in an experimental rehabilitation programme (Getty and Hétu 1991, Hétu and Getty 1991a), discussed in “Family life”, below.

As regards the hearing-impaired, access to public services such as banks, stores, government services and health services is hindered primarily by a lack of knowledge on the part of the institutions. In banks, for example, glass screens may separate clients from tellers, who may be occupied in entering data or filling out forms while talking to clients. The resulting lack of face-to-face visual contact, coupled with unfavourable acoustic conditions and a context in which misunderstanding can have very serious consequences, render this an extremely difficult situation for affected individuals. In health service facilities, patients wait in relatively noisy rooms where their names are called by an employee located at a distance or via a public address system that may be difficult to comprehend. While individuals with hearing loss worry a great deal about being unable to react at the correct time, they generally neglect to inform staff of their hearing problems. There are numerous examples of this type of behaviour.

In most cases, it is possible to prevent these handicap situations by informing staff of the signs and effects of partial deafness and of ways to facilitate communication with affected individuals. A number of public services have already undertaken initiatives aimed at facilitating communication with individuals suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss (Hétu, Getty and Bédard 1994) with results as follows. The use of appropriate graphical or audio visual material allowed the necessary information to be communicated in less than 30 minutes and the effects of such initiatives were still apparent six months after the information sessions. These strategies greatly facilitated communication with the personnel of the services involved. Very tangible benefits were reported not only by clients with hearing loss but also by the staff, who saw their tasks simplified and difficult situations with this type of client prevented.

Social integration

Avoidance of group encounters is one of the most severe consequences of occupationally induced hearing loss (Hétu and Getty 1991b). Group discussions are extremely demanding situations for affected individuals, In this case, the burden of accommodation rests with the affected individual, as he or she can rarely expect the entire group to adopt a favourable rhythm of conversation and mode of expression. Affected individuals have three strategies available to them in these situations:

- reading facial expressions

- using specific communication strategies

- using a hearing aid.

The reading of facial expressions (and lip-reading) can certainly facilitate comprehension of conversations, but requires considerable attention and concentration and cannot be sustained over long periods. This strategy can, however, be usefully combined with requests for repetition, reformulation and summary. Nevertheless, group discussions occur at such a rapid rhythm that it is often difficult to rely upon these strategies. Finally, the use of a hearing aid may improve the ability to follow conversation. However, current amplification techniques do not allow the restoration of frequency discrimination. In other words, both signal and noise are amplified. This often worsens rather than improves the situation for individuals with serious frequency discrimination deficits.

The use of a hearing aid as well as the request for accommodation by the group presupposes that the affected individual feels comfortable revealing his or her condition. As discussed below, interventions aimed at strengthening self-esteem are therefore prerequisites for attempts to supplement auditory capacity.

Family life

The family is the prime locus of the expression of hearing problems caused by occupational hearing loss (Hétu, Jones and Getty 1993). A negative self-image is the essence of the experience of hearing loss, and affected individuals attempt to hide their hearing loss in social interactions by listening more intently or by avoiding overly demanding situations. These efforts, and the anxiety which accompanies them, create a need for release in the family setting, where the need to hide the condition is less strongly felt. Consequently, affected individuals tend to impose their problems on their families and coerce them to adapt to their hearing problems. This takes a toll on spouses and others and causes irritation at having to repeat oneself frequently, tolerate high television volumes and “always be the one to answer the telephone”. Spouses must also deal with serious restrictions in the couples’ social life and with other major changes in family life. Hearing loss limits companionship and intimacy, creates tension, misunderstandings and arguments and disturbs relations with children.

Not only does hearing and communication impairment affect intimacy, but its perception by affected individuals and their family (components 5 and 6 of figure 2) tends to feed frustration, anger and resentment (Hétu, Jones and Getty 1993). Affected individuals frequently do not recognize their impairment and do not attribute their communications problems to a hearing deficit. As a result, they may impose their problems on their families rather than negotiate mutually satisfactory adaptations. Spouses, on the other hand, tend to interpret the problems as a refusal to communicate and as a change in the affected individual’s temperament. This state of affairs may lead to mutual reproaches and accusations, and ultimately to isolation, loneliness and sadness, particularly on the part of the unaffected spouse.

The solution of this interpersonal dilemma requires the participation of both partners. In fact, both require:

- information on the auditory basis of their problems.

- psychosocial support

- training in the use of appropriate supplemental means of communication.

With this in mind, a rehabilitation programme for affected individuals and their spouses has been developed (Getty and Hétu 1991, Hétu and Getty 1991a). The goal of the programme is to stimulate research on the resolution of problems caused by hearing loss, taking into account the passivity and social withdrawal that characterize occupationally induced hearing loss.

Since the stigma associated with deafness is the principal source of these behaviours, it was essential to create a setting in which self-esteem could be restored so as to induce affected individuals to seek out actively solutions to their hearing-related problems. The effects of stigmatization can be overcome only when one is perceived by others as normal regardless of any hearing deficit. The most effective way to achieve this consists of meeting other people in the same situation, as was suggested by workers asked about the most appropriate aid to offer their hearing-impaired colleagues. However, it is essential that these meetings take place outside the workplace, precisely to avoid the risk of further stigmatization (Hétu, Getty and Waridel 1994).

The rehabilitation programme mentioned above was developed with this in mind, the group encounters taking place in a community health department (Getty and Hétu 1991). Recruitment of participants was an essential component of the programme, given the withdrawal and passivity of the target population. Accordingly, occupational health nurses first met with 48 workers suffering from hearing loss and their spouses at their homes. Following an interview on hearing problems and their effects, every couple was invited to a series of four weekly meetings lasting two hours each, held in the evening. These meetings followed a precise schedule aimed at meeting the objectives of information, support and training defined in the programme. Individual follow-up was provided to participants in order to facilitate their access to audio-logical and audioprosthetic services. Individuals suffering from tinnitus were referred to the appropriate services. A further group meeting was held three months after the last weekly meeting.

The results of the programme, collected at the end of the experimental phase, demonstrated that participants and their spouses were more aware of their hearing problems, and were also more confident of resolving them. Workers had undertaken various steps, including technical aids, revealing their impairment to their social group, and expressing their needs in an attempt to improve communication.

A follow-up study, performed with this same group five years after their participation in the programme, demonstrated that the programme was effective in stimulating participants to seek solutions. It also showed that rehabilitation is a complex process requiring several years of work before affected individuals are able to avail themselves of all the means at their disposal to regain their social integration. In most cases, this type of rehabilitation process requires periodic follow-up.

Conclusion

As figure 2 indicates, the meaning that individuals suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss and their associates give to their condition is a key factor in handicap situations. The approaches to rehabilitation proposed in this article explicitly take this factor into account. However, the manner in which these approaches are applied concretely will depend on the specific sociocultural context, since the perception of these phenomena may vary from one context to another. Even within the sociocultural context in which the intervention strategies described above were developed, significant modifications may be necessary. For example, the programme developed for individuals suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss and their spouses (Getty and Hétu 1991) was tested in a population of affected males. Different strategies would probably be necessary in a population of affected females, especially when one considers the different social roles men and women occupy in conjugal and parental relations (Hétu, Jones and Getty 1993). Modifications would be necessary a fortiori when dealing with cultures which differ from that of North America from which the approaches emerged. The conceptual framework proposed (figure 2) can nevertheless be used effectively to orient any intervention aimed at rehabilitating individuals suffering from occupationally induced hearing loss.

Furthermore, this type of intervention, if applied on a large scale, will have important preventive effects on hearing loss itself. The psychosocial aspects of occupationally induced hearing loss hinder both rehabilitation (figure 1) and prevention. The distorted perception of hearing problems delays their recognition, and their dissimulation by severely affected individuals fosters the general perception that these problem are rare and relatively innocuous, even in noisy workplaces. This being so, noise-induced hearing loss is not perceived by workers at risk or by their employers as an important health problem, and the need for prevention is thus not strongly felt in noisy workplaces. On the other hand, individuals already suffering from hearing loss who reveal their problems are eloquent examples of the severity of the problem. Rehabilitation can thus be seen as the first step of a prevention strategy.

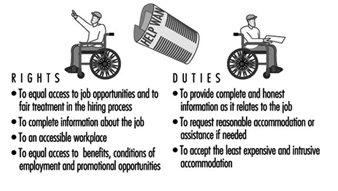

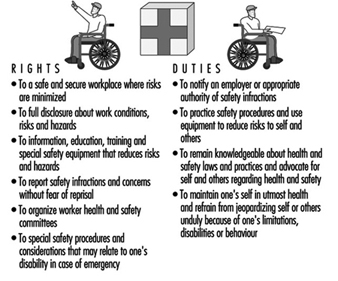

Rights and Duties: An Employer's Perspective

The traditional approach to helping disabled people into work has had little success, and it is evident that something fundamental needs to be changed. For example, the official unemployment rates for disabled people are always at least twice that of their non-disabled peers—often higher. The numbers of disabled people not working often approach 70% (in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada). Disabled people are more likely than their non-disabled peers to live in poverty; for example, in the United Kingdom two-thirds of the 6.2 million disabled citizens have only state benefits as income.

These problems are compounded by the fact that rehabilitation services are often unable to meet employer demand for qualified applicants.

In many countries, disability is not generally defined as an equal opportunities or rights issue. It is thus difficult to encourage corporate best practice which positions disability firmly alongside race and gender as an equal opportunities or diversity priority. Proliferation of quotas or the complete absence of relevant legislation reinforces employer assumptions that disability is primarily a medical or charity issue.

Evidence of the frustrations created by inadequacies inherent in the present system can be seen in growing pressure from disabled people themselves for legislation based on civil rights and/or employment rights, such as exists in the United States, Australia, and, from 1996, in the United Kingdom. It was the failure of the rehabilitation system to meet the needs and expectations of enlightened employers which prompted the UK business community to establish the Employers Forum on Disability.

Employers’ attitudes unfortunately reflect those of the wider society—although this fact is often overlooked by rehabilitation practitioners. Employers share with many others widespread confusion regarding such issues as:

- What is a disability? Who is and who is not disabled?

- Where do I get advice and services to help me recruit and retain disabled people?

- How do I change my organization’s culture and working practices?

- What benefit will best practice on disability bring my business—and the economy in general?

The failure to meet the information and service needs of the employer community constitutes a major hurdle for disabled people wanting work, yet it is rarely addressed adequately by government policy makers or rehabilitation practitioners.

Deep-Rooted Myths that Disadvantage Disabled People in the Labour Market

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governments, indeed all those involved in the medical and employment rehabilitation of persons with disabilities, tend to share a set of deep-rooted, often unspoken assumptions which only further disadvantage the disabled individuals these organizations seek to help:

- “The employer is the problem—indeed, often the adversary.” It is employer attitudes which are often blamed for the failure of disabled people to find jobs, despite the evidence that numerous other factors may well have been highly significant.

- “The employer is not treated either as a client or a customer.” Rehabilitation services do not measure their success by the extent to which they make it easier for the employer to recruit and retain disabled employees. As a result, the unreasonable difficulties created by suppliers of rehabilitation services make it difficult for the well-intentioned and enlightened employer to justify the time, cost and effort required to effect change. The not-so-enlightened employer has his or her reluctance to effect change more than justified by the lack of cooperation from rehabilitation services..

- “Disabled people really cannot compete on merit.” Many service providers have low expectations of disabled people and their potential to work. They find it difficult to promote the “business case” to employers because they themselves doubt that employing people with disability brings genuine mutual benefit. Instead the tone and underlying ethos of their communication with employers stresses the moral and perhaps (occasional) legal obligation in a way which only further stigmatizes disabled people.

- “Disability is not a mainstream economic or business issue. It is best left in the hands of the experts, doctors, rehabilitation providers and charities.” The fact that disability is portrayed in the media and through fund-raising activities as a charity issue, and that disabled people are portrayed as the natural and passive recipients of charity, is a fundamental barrier to the employment of disabled people. It also creates tension in organizations that are trying to find jobs for people, while on the other hand using images which tug at the heartstrings.

The consequence of these assumptions is that:

- Employers and disabled people remain separated by a maze of well-meaning but often uncoordinated and fragmented services which only rarely define success in terms of employer satisfaction.

- Employers and disabled people alike remain excluded from real influence over policy development; only rarely is either party asked to evaluate services from its own perspective and to propose improvements.

We are beginning to see an international trend, typified by the development of “job coach” services, towards acknowledging that successful rehabilitation of disabled people depends upon the quality of service and support available to the employer.

The statement “Better services for employers equals better services for disabled people” must surely come to be much more widely accepted as economic pressures build on rehabilitation agencies everywhere in the light of governments’ retrenchment and restructuring. It is nonetheless very revealing that a recent report by Helios (1994), which summarizes the competencies required by vocational or rehabilitation specialists, fail to make any reference to the need for skills which relate to the employers as customer.

While there is a growing awareness of the need to work with employers as partners, our experience shows that it is difficult to develop and sustain a partnership until the rehabilitation practitioners first meet the needs of the employer as customer and begin to value that “employer as customer” relationship.

Employers’ Roles

At various times and in various situations the system and services position the employer in one or more of the following roles—though only rarely is it articulated. Thus we have the employer as:

- the Problem—“you require enlightenment”

- the Target—“you need education, information, or consciousness raising”

- the Customer—“the employer is encouraged to use us in order to recruit and retain disabled employees”

- the Partner—the employer is encouraged to “enter into a long term, mutually beneficial relationship”.

And at any time during the relationship the employer may be called upon—indeed is typically called upon—to be a funder or philanthropist.

The key to successful practice lies in approaching the employer as “The Customer”. Systems which regard the employer as only “The Problem”, or “The Target”, find themselves in a self-perpetuating dysfunctional cycle.

Factors outside the Employer’s Control

Reliance on perceived employer negative attitudes as the key insight into why disabled people experience high unemployment rates, consistently reinforces the failure to address other highly significant issues which must also be tackled before real change can be brought about.

For example:

- In the United Kingdom, in a recent survey 80% of employers were not aware they had ever had a disabled applicant.

- Benefits and social welfare systems often create financial disincentives for disabled people moving into work.

- Transport and housing systems are notoriously inaccessible; people can look for work successfully only when basic housing, transport and subsistence needs have been met.

- In a recent UK survey, 59% of disabled job seekers were unskilled compared to 23% of their peers. Disabled people, in general, are simply not able to compete in the labour market unless their skill levels are competitive.

- Medical professionals frequently underestimate the extent to which a disabled person can perform in work and are often unable to advise on adaptations and adjustments which might make that person employable.

- Disabled people often find it difficult to obtain high quality career guidance and throughout their lives are subject to the lower expectations of teachers and advisers.

- Quotas and other inappropriate legislation actively undermine the message that disability is an equal opportunities issue.

A legislative system that creates an adversarial or litigious environment can further undermine the job prospects of disabled people because bringing a disabled person into the company could expose the employer to risk.

Rehabilitation practitioners often find it difficult to access expert training and accreditation and are themselves rarely funded to deliver relevant services and products to employers.

Policy Implications

It is vital for service providers to understand that before the employer can effect organizational and cultural change, similar changes are required on the part of the rehabilitation provider. Providers approaching employers as customers need to recognize that actively listening to the employers will almost inevitably trigger the need to change the design and delivery of services.

For example, service providers will find themselves asked to make it easier for the employer to:

- find qualified applicants

- obtain high quality employer-oriented services and advice

- meet disabled people as applicants and colleagues

- understand not just the need for policy change but how to make such change come about

- promote attitude change across their organizations

- understand the business as well as the social case for employing disabled people

Attempts at significant social policy reforms related to disability are undermined by the failure to take into account the needs, expectations and legitimate requirements of the people who will largely determine success—that is, the employers. Thus, for example, the move to ensure that people currently in sheltered workshops obtain mainstream work frequently fails to acknowledge that it is only employers who are able to offer that employment. Success therefore is limited, not only because it is unnecessarily difficult for the employers to make opportunities available but also because of the missed added value resulting from active collaboration between employers and policy makers.

Potential for Employer Involvement

Employers can be encouraged to contribute in numerous ways to making a systematic shift from sheltered employment to supported or competitive employment. Employers can:

- advise on policy—that is, on what needs to be done which would make it easier for employers to offer work to disabled candidates.

- offer advice on the competencies required by disabled individ-uals if they are to be successful in obtaining work.

- advise on the competencies required by service providers if they are to meet employer expectations of quality provision.

- evaluate sheltered workshops and offer practical advice on how to manage a service that is most likely to enable people to move into mainstream work.

- offer work experience to rehabilitation practitioners, who thus gain an understanding of a particular industry or sector and are better able to prepare their disabled clients.

- offer on-the-job assessments and training to disabled individuals.

- offer mock interviews and be mentors to disabled job seekers.

- loan their own staff to work inside the system and/or its institutions.