Children categories

17. Disability and Work (10)

17. Disability and Work

Chapter Editors: Willi Momm and Robert Ransom

Table of Contents

Figures

Disability: Concepts and Definitions

Willi Momm and Otto Geiecker

Case Study: Legal Classification of Disabled People in France

Marie-Louise Cros-Courtial and Marc Vericel

Social Policy and Human Rights: Concepts of Disability

Carl Raskin

International Labour Standards and National Employment Legislation in Favour of Disabled Persons

Willi Momm and Masaaki Iuchi

Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment Support Services

Erwin Seyfried

Disability Management at the Workplace: Overview and Future Trends

Donald E. Shrey

Rehabilitation and Noise-induced Hearing Loss

Raymond Hétu

Rights and Duties: An Employer’s Perspective

Susan Scott-Parker

Case Study: Best Practices Examples

Rights and Duties: Workers’ Perspective

Angela Traiforos and Debra A. Perry

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

18. Education and Training (9)

18. Education and Training

Chapter Editor: Steven Hecker

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Introduction and Overview

Steven Hecker

Principles of Training

Gordon Atherley and Dilys Robertson

Worker Education and Training

Robin Baker and Nina Wallerstein

Case Studies

Evaluating Health and Safety Training: A Case Study in Chemical Workers Hazardous Waste Worker Education

Thomas H. McQuiston, Paula Coleman, Nina Wallerstein, A.C. Marcus, J.S. Morawetz, David W. Ortlieb and Steven Hecker

Environmental Education and Training: The State of Hazardous Materials Worker Education in the United States

Glenn Paulson, Michelle Madelien, Susan Sink and Steven Hecker

Worker Education and Environmental Improvement

Edward Cohen-Rosenthal

Safety and Health Training of Managers

John Rudge

Training of Health and Safety Professionals

Wai-On Phoon

A New Approach to Learning and Training:A Case Study by the ILO-FINNIDA African Safety and Health Project

Antero Vahapassi and Merri Weinger

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

19. Ethical Issues (10)

19. Ethical Issues

Chapter Editor: Georges H. Coppée

Table of Contents

Codes and Guidelines

Colin L. Soskolne

Responsible Science: Ethical Standards and Moral Behaviour in Occupational Health

Richard A. Lemen and Phillip W. Strine

Ethical Issues in Occupational Health and Safety Research

Paul W. Brandt-Rauf and Sherry I. Brandt-Rauf

Ethics in the Workplace: A Framework for Moral Judgement

Sheldon W. Samuels

Surveillance of the Working Environment

Lawrence D. Kornreich

Canons of Ethical Conduct and Interpretive Guidelines

Ethical Issues: Information and Confidentiality

Peter J. M. Westerholm

Ethics in Health Protection and Health Promotion

D. Wayne Corneil and Annalee Yassi

Case Study: Drugs and Alcohol in the Workplace - Ethical Considerations

Behrouz Shahandeh and Robert Husbands

International Code of Ethics for Occupational Health Professionals

International Commission on Occupational Health

20. Development, Technology and Trade (10)

20. Development, Technology and Trade

Chapter Editor: Jerry Jeyaratnam

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Occupational Health Trends in Development

Jerry Jeyaratnam

Industrialized Countries and Occupational Health and Safety

Toshiteru Okubo

Case Studies in Technological Change

Michael J. Wright

Small Enterprises and Occupational Health and Safety

Bill Glass

Transfer of Technology and Technological Choice

Joseph LaDou

Free-Trade Agreements

Howard Frumkin

Case Study: World Trade Organization

Product Stewardship and the Migration of Industrial Hazards

Barry Castleman

Economic Aspects of Occupational Health and Safety

Alan Maynard

Case Study: Industrialization and Occupational Health Problems in China

Su Zhi

Tables

Click a link below to view table in the article context.

1. Small-scale enterprises

2. Information from foreign investors

3. Costs of work accidents & health (Britain)

4. Types of economic evaluation

5. Development of China’s township enterprises

6. Country HEPS & OHS coverages in China

7. Compliance rates of 6 hazards in worksites

8. Detectable rates of occupational diseases

9. Hazardous working & employers, China

10. OHS background in foreign-funded enterprises

11. Routine instruments for OHS, 1990, China

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

21. Labour Relations and Human Resources Management (12)

21. Labour Relations and Human Resources Management

Chapter Editor: Anne Trebilcock

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Labour Relations and Human Resources Management: An Overview

Anne Trebilcock

Rights of Association and Representation

Breen Creighton

Collective Bargaining and Safety and Health

Michael J. Wright

National Level Tripartite and Bipartite Cooperation on Health and Safety

Robert Husbands

Forms of Workers’ Participation

Muneto Ozaki and Anne Trebilcock

Case Study: Denmark: Worker Participation in Health and Safety

Anne Trebilcock

Consultation and Information on Health and Safety

Marco Biagi

Labour Relations Aspects of Training

Mel Doyle

Labour Relations Aspects of Labour Inspection

María Luz Vega Ruiz

Collective Disputes over Health and Safety Issues

Shauna L. Olney

Individual Disputes over Health and Safety Issues

Anne Trebilcock

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Practical activities-health & safety training

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

22. Resources: Information and OSH (5)

22. Resources: Information and OSH

Chapter Editor: Jukka Takala

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Information: A Precondition for Action

Jukka Takala

Finding and Using Information

P.K. Abeytunga, Emmert Clevenstine, Vivian Morgan and Sheila Pantry

Information Management

Gordon Atherley

Case study: Malaysian Information Service on Pesticide Toxicity

D.A. Razak, A.A. Latiff, M.I. A. Majid and R. Awang

Case Study: A Successful Information Experience in Thailand

Chaiyuth Chavalitnitikul

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Some core periodicals in occupational health & safety

2. Standard search form

3. Information required in occupational health & safety

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

23. Resources, Institutional, Structural and Legal (20)

23. Resources, Institutional, Structural and Legal

Chapter Editors: Rachael F. Taylor and Simon Pickvance

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Institutional, Structural and Legal Resources: Introduction

Simon Pickvance

Labour Inspection

Wolfgang von Richthofen

Civil and Criminal Liability in Relation to Occupational Safety and Health

Felice Morgenstern (adapted)

Occupational Health as a Human Right

Ilise Levy Feitshans

Community Level

Community-Based Organizations

Simon Pickvance

Right to Know: The Role of Community-Based Organizations

Carolyn Needleman

The COSH Movement and Right to Know

Joel Shufro

Regional and National Examples

Occupational Health and Safety: The European Union

Frank B. Wright

Legislation Guaranteeing Benefits for Workers in China

Su Zhi

Case Study: Exposure Standards in Russia

Nikolai F. Izmerov

International Governmental and Non-Governmental Organizations

International Cooperation in Occupational Health: The Role of International Organizations

Georges H. Coppée

The United Nations and Specialized Agencies

Contact Information for the United Nations Organization

International Labour Organization

Georg R. Kliesch

Case Study: ILO Conventions--Enforcement Procedures

Anne Trebilcock

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

Lawrence D. Eicher

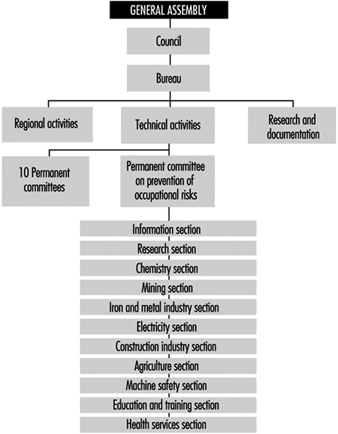

International Social Security Association (ISSA)

Dick J. Meertens

Addresses of the ISSA International Sections

International Commission on Occupational Health (ICOH)

Jerry Jeyaratnam

International Association of Labour Inspection (IALI)

David Snowball

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Bases for Russian vs. American standards

2. ISO technical committees for OHS

3. Venues of triennial congresses since 1906

4. ICOH committees & working groups, 1996

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

24. Work and Workers (6)

24. Work and Workers

Chapter Editors: Jeanne Mager Stellman and Leon J. Warshaw

Table of Contents

Figures

Work and Workers

Freda L. Paltiel

Shifting Paradigms and Policies

Freda L. Paltiel

Health, Safety and Equity in the Workplace

Joan Bertin

Precarious Employment and Child Labour

Leon J. Warshaw

Transformations in Markets and Labour

Pat Armstrong

Globalizing Technologies and the Decimation/Transformation of Work

Heather Menzies

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

25. Worker's Compensation Systems (1)

25. Worker's Compensation Systems

Chapter Editor: Terence G. Ison

Table of Contents

Overview

Terence G. Ison

Part One: Workers' Compensation

Coverage

Organization, Administration and Adjudication

Eligibility for Benefits

Multiple Causes of Disability

Subsequent Consequential Disabilities

Compensable Losses

Multiple Disabilities

Objections to Claims

Employer Misconduct

Medical Aid

Money Payments

Rehabilitation and Care

Obligations to Continue the Employment

Finance

Vicarious Liability

Health and Safety

Claims against Third Parties

Social Insurance and Social Security

Part Two: Other Systems

Accident Compensation

Sick Pay

Disability Insurance

Employers’ Liability

26. Topics in Workers' Compensation Systems (6)

26. Topics in Workers' Compensation Systems

Chapter Editors: Paule Rey and Michel Lesage

Table of Contents

Tables

Work-Related Diseases and Occupational Diseases: The ILO International List

Michel Lesage

Workers’ Compensation: Trends and Perspectives

Paule Rey

Prevention, Rehabilitation and Compensation in the German Accident Insurance System

Dieter Greiner and Andreas Kranig

Employment Injuries Insurance and Compensation in Israel

Haim Chayon

Workers’ Accident Compensation in Japan

Kazutaka Kogi and Haruko Suzuki

Country Case Study: Sweden

Peter Westerholm

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Proposed ILO list of occupational diseases

2. Recipients of benefits in Israel

3. Premium rates in Japan

4. Enterprises, workers & costs in Japan

5. Payment of benefits by industry in Japan

The United Nations and Specialized Agencies

* This article is adapted from Basic Facts About the United Nations (United Nations 1992).

Origin of the United Nations

The United Nations was, in 1992, an organization of 179 nations legally committed to cooperate in supporting the principles and purposes set out in its Charter. These include commitments to eradicate war, promote human rights, maintain respect for justice and international law, promote social progress and friendly relations among nations, and use the Organization as a centre to harmonize their actions in order to attain these ends.

The United Nations Charter was written in the closing days of the Second World War by the representatives of 50 governments meeting at the United Nations Conference on International Organization in 1945. The Charter was drafted on the basis of proposals worked out by the representatives of China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States. It was adopted and signed on 26 June 1945.

To millions of refugees from war and persecution, the United Nations has provided shelter and relief. It has acted as a major catalyst in the evolution of 100 million people from colonial rule to independence and sovereignty. It has established peace-keeping operations many times to contain hostilities and to help resolve conflicts. It has expanded and codified international law. It has wiped smallpox from the face of the planet. In the five decades of its existence, the Organization has adopted some 70 legal instruments promoting or obligating respect for human rights, thus facilitating an historic change in the popular expectation of freedom throughout the world.

Membership

The Charter declares that membership of the UN is open to all peace-loving nations which accept its obligations and which, in the judgement of the Organization, are willing and able to carry out these obligations. States are admitted to membership by the General Assembly on the recommendation of the Security Council. The Charter also provides for the suspension or expulsion of Members for violation of the principles of the Charter, but no such action has ever been taken.

Official Languages

Under the Charter the official languages of the United Nations are Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish. Arabic has been added as an official language of the General Assembly, the Security Council and the Economic and Social Council.

Structure

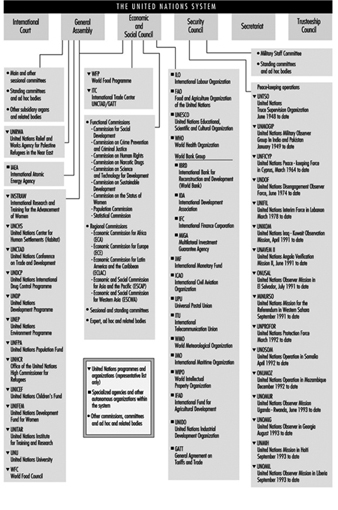

The United Nations is a complex network consisting of six main organs with a large number of related programmes, agencies, commissions and other bodies. These related bodies have different legal status (some are autonomous, some are under the direct authority of the UN and so on), objectives and areas of responsibility, but the system displays a very high level of cooperation and collaboration. Figure 1 provides a schematic illustration of the structure of the system and some of the links between the different bodies. For further information, reference should be made to: Basic Facts About the United Nations (1992).

Figure 1. The Charter established six principal organs of the United Nations

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice is the principal judicial organ of the UN. The Court is open to the parties to its Statute, which automatically includes all Members of the UN. Other States can refer cases to the Court under conditions laid down by the Security Council. In addition, the Security Council may recommend that a legal dispute be referred to the Court. Only States may be party to cases before the Court (i.e., the Court is not open to individuals). Both the General Assembly and the Security Council can ask the Court for an advisory opinion on any legal question; other organs of the UN and the specialized agencies, when authorized by the General Assembly, can ask for advisory opinions on legal questions within the scope of their activities (for example, the International Labour Organization could request an advisory opinion relating to an international labour standard).

The jurisdiction of the Court covers all matters provided for in the UN Charter or in treaties or conventions in force, and all other questions which States refer to it. In deciding cases, the Court is not restricted to principles of law contained in treaties or conventions, but may employ the entire sphere of international law (including customary law).

The General Assembly

The General Assembly is the main deliberative organ. It is composed of representatives of all Member States, each of which has one vote. Decisions on important questions, such as those on peace and security, admission of new Members and budgetary matters, require a two-thirds majority. Decisions on other questions are reached by a simple majority.

The functions and powers of the General Assembly include the consideration of and formulation of recommendations on the principles of cooperation in the maintenance of international peace and security, including disarmament and the regulation of armaments. The General Assembly also initiates studies and makes recommendations to promote international political cooperation, the development and codification of international law, the realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, and international collaboration in the economic, social, cultural, educational and health fields. It receives and deliberates on reports from the Security Council and other UN organs; considers and approves the UN budget and apportions the contributions among Members; and elects the non-permanent members of the Security Council, the members of the Economic and Social Council and those members of the Trusteeship Council that are elected. The General Assembly also elects jointly with the Security Council the Judges of the International Court of Justice and, on the recommendation of the Security Council, appoints the Secretary-General.

At the beginning of each regular session, the General Assembly holds a general debate, in which Member States express their views on a wide range of matters of international concern. Because of the great number of questions which the General Assembly is called upon to consider (over 150 agenda items at the 1992 session, for example), the Assembly allocates most questions to its seven main committees:

- First Committee (disarmament and related international security matters)

- Special Political Committee

- Second Committee (economic and financial matters)

- Third Committee (social, humanitarian and cultural matters)

- Fourth Committee (decolonization matters)

- Fifth Committee (administrative and budgetary matters)

- Sixth Committee (legal matters).

Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC)

ECOSOC was established by the Charter as the principal organ to coordinate the economic and social work of the UN and the specialized agencies and institutions. The Economic and Social Council serves as the central forum for the discussion of international economic and social issues of a global or inter-disciplinary nature and the formulation of policy recommendations on those issues, and works to promote respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all. ECOSOC may make or initiate studies and reports and recommendations on international economic, social, cultural, educational, health and related matters, and call international conferences and prepare draft conventions for submission to the General Assembly. Other powers and functions include the negotiation of agreements with the specialized agencies defining their relationship with the UN and the coordination of their activities, and consultation with NGOs concerned with matters with which the Council deals.

Subsidiary bodies

The subsidiary machinery of the Council includes functional and regional commissions, six standing committees (for example, the Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations and on Transnational Corporations) and a number of standing expert bodies on such subjects as crime prevention and control, development planning, and the transport of dangerous goods.

Relations with non-governmental organizations

Over 900 NGOs have consultative status with the Council, with varying levels of involvement. These NGOs may send observers to public meetings of the Council and its subsidiary bodies and may submit written statements relevant to the Council’s work. They may also consult with the UN Secretariat on matters of mutual concern.

Security Council

The Security Council has primary responsibility, under the Charter, for the maintenance of international peace and security. While other organs of the UN make recommendations to governments, the Council alone has the power to take decisions which Member States are obligated under the Charter to carry out.

Secretariat

The Secretariat, an international staff working at UN Headquarters in New York and in the field, carries out the diverse day-to-day work of the Organization. It services the other organs of the UN and administers the programmes and policies laid down by them. At its head is the Secretary-General, who is appointed by the General Assembly on the recommendation of the Security Council for a term of five years.

Trusteeship Council

In setting up an International Trusteeship System, the Charter established the Trusteeship Council as one of the main organs of the UN and assigned to it the task of supervising the administration of Trust Territories placed under the Trusteeship System. Major goals of the System are to promote the advancement of the inhabitants of Trust Territories and their progressive development towards self-government or independence.

The Role of the United Nations System in Occupational Health and Safety

While the improvement of working conditions and environment will normally be part of national policy to further economic development and social progress in accordance with national objectives and priorities, a measure of international harmonization is necessary to ensure that the quality of the working environment everywhere is compatible with workers’ health and welfare, and to assist Member States to this effect. This is, essentially, the role of the UN system in this field.

Within the UN system, many organizations and bodies play a role in the improvement of the working conditions and the working environment. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has a constitutional mandate to improve working conditions and environment to humanize work; its tripartite structure can ensure that its international standards have a direct impact on national legislation, policies and practices and is discussed in a separate article in this chapter.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has a mandate in occupational health derived from its Constitution, which identified WHO as “the directing and coordinating authority on international health work”, and stated WHO’s functions which include the “promotion of ...economic and working conditions and other aspects of environmental hygiene”. Additional mandates are derived from various resolutions of the World Health Assembly and Executive Board. WHO’s occupational health programme aims to promote the knowledge and control of workers’ health problems, including occupational and work-related diseases, and to cooperate with countries in the development of health care programmes for workers, particularly those who are generally underserviced. The WHO, in collaboration with the ILO, UNEP and other organizations, undertakes technical cooperation with Member States, produces guidelines, and carries out field studies and occupational health training and personnel development. The WHO has set up the GEENET—the Global Environmental Epidemiology Network—which includes institutions and individuals from all over the world who are actively involved in research and training on environmental and occupational epidemiology. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has been established as an independent research institute, but within the framework of the WHO. The statutes of the Agency set out its mission as “planning, promoting and developing research in all phases of the causation, treatment and prevention of cancer”. Since the start of its research activity, the Agency has devoted itself to studying the causes of cancer present in the human environment, in the belief that identification of a carcinogenic agent was the first and necessary step towards reducing or removing the causal agent from the environment, with the aim of preventing cancer that it might have caused. The Agency’s research activities fall into two main groups—epidemiological and laboratory-based experimental but there is considerable interaction between these groups in the actual research projects undertaken.

Besides these two organizations with a central focus on work and health, respectively, several UN bodies include health and safety matters within their specific sectoral or geographical functions:

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has the mandate to safeguard and enhance the environment for the benefit of present and future generations, including the working environment. It has a basic coordinating and catalytic function for environment in general within the UN system. It discharges this function through programme coordination and the support of activities by the Environment Fund. In addition to its general mandate, UNEP’s specific mandate with regard to the working environment stems from Recommendations 81 and 83 of the UN Conference on the Human Environment, and UNEP Governing Council Decisions requesting the Executive Director to integrate the principles and objectives related to the improvement of the working environment fully into the framework of the environment programme. UNEP is also required to collaborate with the appropriate organizations of workers and employers, in the development of a coordinated system-wide action programme on the working and living environment of workers, and with the UN bodies concerned (for example, UNEP cooperates with the WHO and the ILO in the International Programme on Chemical Safety).

UNEP maintains the International Register of Potentially Toxic Chemicals (IRPTC), which strives to bridge the gap between the world’s chemical knowledge and those who need to use it. UNEP’s network of environmental agreements is also having an ever-increasing international effect, and gathering momentum (for example, the historic Vienna Convention and the Montreal Protocol on the protection of the ozone layer).

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is concerned with hazards resulting from ionizing radiation associated with the nuclear fuel cycle. The IAEA encourages and guides the development of peaceful uses of atomic energy, establishes standards for nuclear safety and environmental protection, aids member countries through technical cooperation, and fosters the exchange of scientific and technical information on nuclear energy. The activities of the Agency in the area of radiological protection of workers involve the development of these standards; preparation of safety guides, codes of practice and manuals; holding of scientific meetings for exchange of information or preparation of manuals or technical guidebooks; organizing training courses, visiting seminars and study tours; development of technical expertise in developing Member States through the awards of research contracts and fellowships; and helping the developing Member States in the organization of radiation protection programmes through the provision of technical assistance, experts’ services, advisory missions, and advisory services on nuclear law regulatory matters.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the World Bank have included provisions on occupational safeguards in development assistance agreements. The UNDP is engaged in a large number of projects designed to assist developing countries to build up their nascent economies and raise their living standards. Several thousand internationally recruited experts are kept steadily at work in the field. Several amongst these projects are devoted to the improvement of occupational safety and health standards in industry and other walks of economic life, the implementation of which is entrusted to the ILO and WHO. Such field projects may range from the provision of short-term consultancy to more massive assistance over a period of several years for the establishment of fully fledged occupational safety and health institutes designed to provide training, applied field research and direct service to places of employment.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) deals with the safety of workers on board ships. IMO provides a forum for member governments and interested organizations to exchange information and endeavour to solve problems connected with technical, legal and other questions concerning shipping and the prevention of marine pollution by ships. IMO has drafted a number of conventions and recommendations which governments have adopted and which have entered into force. Among them are international conventions for the safety of life at sea, the prevention of marine pollution by ships, the training and certification of seafarers, the prevention of collisions at sea, several instruments dealing with liability and compensation, and many others. IMO has also adopted several hundred recommendations dealing with subjects such as the maritime transport of dangerous goods, maritime signals, safety for fishermen and fishing vessels, and the safety of nuclear merchant ships.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has a role in protecting agricultural workers against hazards resulting from the use of pesticides, farm tools and machinery. A number of activities of FAO are directly or indirectly concerned with occupational safety and health and ergonomics in agricultural, forestry and fishery work. In fishery activities, FAO collaborates at the secretariat level with the ILO and the IMO on the IMO Sub-Committee on Safety of Fishing Vessels and participates actively in the work of the IMO Sub-Committee on Standards of Training and Watchkeeping. FAO collaborates with ILO in regard to conditions of work in the fishing industry. In forestry activities, the FAO/ECE/ILO Committee on Forest Working Techniques and Training of Forest Workers deals at the interagency level with health and safety matters. Field projects and publications in this area cover such aspects as safety in logging and industry and heat stress in forest work.

In the agricultural field some of the diseases of economic importance in livestock also present hazards to persons handling livestock and animal products (e.g., brucellosis, tuberculosis, leptospirosis, anthrax, rabies, Rift Valley fever). For these disease-related activities, close liaison is maintained with WHO through joint committees. FAO is also concerned with the harmonization of registration requirements for pesticides and the assessment of pesticide residues in food and in the environment. As regards atomic energy in food and agriculture, programmes are coordinated with the IAEA in order to assist scientists of developing countries to make safe and effective use of relevant isotope techniques (e.g., the use of radio-labelled enzyme substrates for detecting occupational exposure to insecticides).

The UN Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) aims to accelerate the industrial development of developing countries. It is concerned with occupational safety and health hazards, environment and hazardous waste management in relation to the industrialization process.

Regional UN Economic Commissions play a role in promoting more effective and harmonized action within their regions.

The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) is concerned with the occupational aspects of the international transfer of goods, services and technology.

Ethical Issues in Occupational Health and Safety Research

In the last several decades, considerable effort has been devoted to defining and addressing the ethical issues that arise in the context of biomedical experimentation. Central ethical concerns that have been identified in such research include the relationship of risks to benefits and the ability of research subjects to give informed and voluntary prior consent. Assurance of adequate attention to these issues has normally been achieved by review of research protocols by an independent body, such as an Institutional Review Board (IRB). For example, in the United States, institutions engaging in biomedical research and receiving Public Health Service research funds are subject to strict federal governmental guidelines for such research, including review of protocols by an IRB, which considers the risks and benefits involved and the obtaining of informed consent of research subjects. To a large degree, this is a model which has come to be applied to scientific research on human subjects in democratic societies around the world (Brieger et al. 1978).

Although the shortcomings of such an approach have been debated—for example, in a recent Human Research Report, Maloney (1994) says some institutional review boards are not doing well on informed consent—it has many supporters when it is applied to formal research protocols involving human subjects. The deficiencies of the approach appear, however, in situations where formal protocols are lacking or where studies bear a superficial resemblance to human experimentation but do not clearly fall within the confines of academic research at all. The workplace provides one clear example of such a situation. Certainly, there have been formal research protocols involving workers that satisfy the requirements of risk-benefit review and informed consent. However, where the boundaries of formal research blur into less formal observances concerning workers’ health and into the day-to-day conduct of business, ethical concerns over risk-benefit analysis and the assurance of informed consent may be easily put aside.

As one example, consider the Dan River Company “study” of cotton dust exposure to its workers at its Danville, Virginia, plant. When the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) cotton dust standard went into effect following US Supreme Court review in 1981, the Dan River Company sought a variance from compliance with the standard from the state of Virginia so that it could conduct a study. The purpose of the study was to address the hypothesis that byssinosis is caused by micro-organisms contaminating the cotton rather than by the cotton dust itself. Thus, 200 workers at the Danville plant were to be exposed to varying levels of the micro-organism while being exposed to cotton dust at levels above the standard. The Dan River Company applied to OSHA for funding for the project (technically considered a variance from the standard, and not human research), but the project was never formally reviewed for ethical concerns because OSHA does not have an IRB. Technical review by an OSHA toxicologist cast serious doubt on the scientific merit of the project, which in and of itself should raise ethical questions, since incurring any risk in a flawed study might be unacceptable. However, even if the study had been technically sound, it is unlikely to have been approved by any IRB since it “violated all the major criteria for protection of subject welfare” (Levine 1984). Plainly, there were risks to the worker-subjects without any benefits for them individually; major financial benefits would have gone to the company, while benefits to society in general seemed vague and doubtful. Thus, the concept of balancing risks and benefits was violated. The workers’ local union was informed of the intended study and did not protest, which could be construed to represent tacit consent. However, even if there was consent, it might not have been entirely voluntary because of the unequal and essentially coercive relationship between the employer and the employees. Since Dan River Company was one of the most important employers in the area, the union’s representative admitted that the lack of protest was motivated by fear of a plant closing and job losses. Thus, the concept of voluntary informed consent was also violated.

Fortunately, in the Dan River case, the proposed study was dropped. However, the questions it raises remain and extend far beyond the bounds of formal research. How can we balance benefits and risks as we learn more about threats to workers’ health? How can we guarantee informed and voluntary consent in this context? To the extent that the ordinary workplace may represent an informal, uncontrolled human experiment, how do these ethical concerns apply? It has been suggested repeatedly that workers may be the “miner’s canary” for the rest of society. On an ordinary day in certain workplaces, they may be exposed to potentially toxic substances. Only when adverse reactions are noted does society initiate a formal investigation of the substance’s toxicity. In this way, workers serve as “experimental subjects” testing chemicals previously untried on humans.

Some commentators have suggested that the economic structure of employment already addresses risk/benefit and consent considerations. As to the balancing of risks and benefits, one could argue that society compensates hazardous work with “hazard pay”—directly increasing the benefits to those who assume the risk. Furthermore, to the extent that the risks are known, right-to-know mechanisms provide the worker with the information necessary for an informed consent. Finally, armed with the knowledge of the benefits to be expected and the risks assumed, the worker may “volunteer” to take the risk or not. However, “volunteer-ness” requires more than information and an ability to articulate the word no. It also requires freedom from coercion or undue influence. Indeed, an IRB would view a study in which the subjects received significant financial compensation—“hazard pay”, as it were—with a sceptical eye. The concern would be that powerful incentives minimize the possibility for truly free consent. As in the Dan River case, and as noted by the US Office of Technology Assessment,

(t)his may be especially problematic in an occupational setting where workers may perceive their job security or potential for promotion to be affected by their willingness to participate in research (Office of Technology Assessment 1983).

If so, cannot the worker simply choose a less hazardous occupation? Indeed, it has been suggested that the hallmark of a democratic society is the right of the individual to choose his or her work. As others have pointed out, however, such free choice may be a convenient fiction since all societies, democratic or otherwise,

have mechanisms of social engineering that accomplish the task of finding workers to take available jobs. Totalitarian societies accomplish this through force; democratic societies through a hegemonic process called freedom of choice (Graebner 1984).

Thus, it seems doubtful that many workplace situations would satisfy the close scrutiny required of an IRB. Since our society has apparently decided that those fostering our biomedical progress as human research subjects deserve a high level of ethical scrutiny and protection, serious consideration should be given before denying this level of protection to those who foster our economic progress: the workers.

It has also been argued that, given the status of the workplace as a potentially uncontrolled human experiment, all involved parties, and workers in particular, should be committed to the systematic study of the problems in the interest of amelioration. Is there a duty to produce new information concerning occupational hazards through formal and informal research? Certainly, without such research, the workers’ right to be informed is hollow. The assertion that workers have an active duty to allow themselves to be exposed is more problematic because of its apparent violation of the ethical tenet that people should not be used as a means in the pursuit of benefits to others. For example, except in very low risk cases, an IRB may not consider benefits to others when it evaluates risk to subjects. However, a moral obligation for workers’ participation in research has been derived from the demands of reciprocity, i.e., the benefits that may accrue to all affected workers. Thus, it has been suggested that “it will be necessary to create a research environment within which workers—out of a sense of the reciprocal obligations they have—will voluntarily act upon the moral obligation to collaborate in work, the goal of which is to reduce the toll of morbidity and mortality” (Murray and Bayer 1984).

Whether or not one accepts the notion that workers should want to participate, the creation of such an appropriate research environment in the occupational health setting requires careful attention to the other possible concerns of the worker-subjects. One major concern has been the potential misuse of data to the detriment of the workers individually, perhaps through discrimination in employability or insurability. Thus, due respect for the autonomy, equity and privacy considerations of worker-subjects mandates the utmost concern for the confidentiality of research data. A second concern involves the extent to which the worker-subjects are informed of research results. Under normal experimental situations, results would be available routinely to subjects. However, many occupational studies are epidemiological, e.g., retrospective cohort studies, which traditionally have required no informed consent or notification of results. Yet, if the potential for effective interventions exists, the notification of workers at high risk of disease from past occupational exposures could be important for prevention. If no such potential exists, should workers still be notified of findings? Should they be notified if there are no known clinical implications? The necessity for and logistics of notification and follow-up remain important, unresolved questions in occupational health research (Fayerweather, Higginson and Beauchamp 1991).

Given the complexity of all of these ethical considerations, the role of the occupational health professional in workplace research assumes great importance. The occupational physician enters the workplace with all of the obligations of any health care professional, as state by the International Commission on Occupational Health and reprinted in this chapter:

Occupational health professionals must serve the health and social well-being of the workers, individually and collectively. The obligations of occupational health professionals include protecting the life and the health of workers, respecting human dignity and promoting the highest ethical principles in occupational health policies and programmes.

In addition, the participation of the occupational physician in research has been viewed as a moral obligation. For example, the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine’s Code of Ethical Conduct specifically states that “(p)hysicians should participate in ethical research efforts as appropriate” (1994). However, as with other health professionals, the workplace physician functions as a “double agent”, with the potentially conflicting responsibilities that stem from caring for the workers while being employed by the corporation. This type of “double agent” problem is not unfamiliar to the occupational health professional, whose practice often involves divided loyalties, duties and responsibilities to workers, employers and other parties. However, the occupational health professional must be particularly sensitive to these potential conflicts because, as discussed above, there is no formal independent review mechanism or IRB to protect the subjects of workplace exposures. Thus, in large part it will fall to the occupational health professional to ensure that the ethical concerns of risk-benefit balancing and voluntary informed consent, among others, are given appropriate attention.

International Labour Organization

The ILO is one of 18 specialized agencies of the United Nations. It is the oldest international organization within the UN family, and was founded by the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919 after the First World War.

Foundation of the ILO

Historically, the ILO is the outgrowth of the social thought of the 19th century. Conditions of workers in the wake of the industrial revolution were increasingly seen to be intolerable by economists and sociologists. Social reformers believed that any country or industry introducing measures to improve working conditions would raise the cost of labour, putting it at an economic disadvantage compared to other countries or industries. That is why they laboured with such persistence to persuade the powers of Europe to make better working conditions and shorter hours of work the subject of international agreements. After 1890 three international conferences were held on the subject: the first was convened jointly by the German emperor and the Pope in Berlin in 1890; another conference held in 1897 in Brussels was stimulated by the Belgian authorities; and a third, held in 1906 in Bern, Switzerland, adopted for the first time two international agreements on the use of white phosphorus (manufacturing of matches) and on the ban of night work in industry by women. As the First World War had prevented any further activities on the internationalization of labour conditions, the Peace Conference of Versailles, in its intention to eradicate the causes of future war, took up the goals of the pre-war activities and established a Commission on International Labour Legislation. The elaborated proposal of the Commission on the establishment of an international body for the protection of workers became Part XIII of the Treaty of Versailles; to this day, it remains the charter under which the ILO operates.

The first International Labour Conference was held in Washington DC, in October 1919; the Permanent Secretariat of the Organization—the International Labour Office—was installed in Geneva, Switzerland.

The Constitution of the International Labour Organization

Permanent peace worldwide, justice and humanity were and are the motivations for the International Labour Organization, best expressed in the Preamble to the Constitution. It reads:

Whereas universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice;

And whereas conditions of labour exist involving such injustice, hardship and privation to large numbers of people as to produce unrest so great that the peace and harmony of the world are imperilled; and an improvement of those conditions is urgently required, as for example, by

- the regulation of the hours of work, including establishment of a maximum working day and week,

- the regulation of the labour supply,

- the prevention of unemployment,

- the provision of an adequate living wage,

- the protection of the worker against sickness, disease and injury arising out of his employment,

- the protection of children, young persons and women,

- the provision for old age and injury,

- the protection of the interests of workers when employed in countries other than their own,

- the recognition of the principle of equal remuneration for work of equal value,

- the recognition of the principle of freedom of association,

- the organization of vocational and technical education and other measures;

Whereas also the failure of any nation to adopt humane conditions of labour is an obstacle in the way of other nations which desire to improve the conditions in their own countries;

The High Contracting Parties, moved by sentiments of justice and humanity as well as by the desire to secure the permanent peace of the world, and with a view to attaining the objectives set forth in this Preamble, agree to the following Constitution of the International Labour Organisation. …”

The aims and purposes of the International Labour Organization in a modernized form are embodied in the Philadelphia Declaration, adopted in 1944 at the International Labour Conference in Philadelphia, USA. The Declaration is now an Annex to the Constitution of the ILO. It proclaims the right of all human beings “to pursue both their material well being and their spiritual development in conditions of freedom and dignity, of economic security and equal opportunity”. It further states that “poverty anywhere constitutes a danger to prosperity everywhere”.

The task of the ILO as determined in Article 1 of the Constitution is the promotion of the objects set forth in the Preamble and in the Philadelphia Declaration.

The International Labour Organization and its Structure

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is composed of 173 States. Any member of the United Nations may become a member of the ILO by communicating to the Director-General of the ILO its formal acceptance of the obligations of the Constitution. Non-Member States of the UN may be admitted by a vote of the International Labour Conference (Switzerland is a member of the ILO but not, however, of the UN) (Constitution, Article 1). Representation of Member States at the ILO has a structure which is unique within the UN family. In the UN and in all other specialized UN agencies, representation is only by government personnel: ministers, their deputies, or authorized representatives. However, at the ILO the concerned groups of society are part of the Member States’ representation. Representatives consist of government delegates, generally from the ministry of labour, and delegates representing the employers and the workers of each of the members (Constitution, Article 3). This is the ILO’s fundamental concept of tripartism.

The International Labour Organization consists of:

- the International Labour Conference, an annual Conference of representatives of all members

- the Governing Body, composed of 28 government representatives, 14 employers’ representatives, and 14 workers’ representatives

- the International Labour Office—the permanent secretariat of the organization—which is controlled by the Governing Body.

The International Labour Conference—also called the World Parliament of Labour—meets regularly in June each year with about 2,000 participants, delegates and advisers. The agenda of the Conference includes the discussion and adoption of international agreements (the ILO’s Conventions and Recommendations), the deliberation of special labour themes in order to frame future policies, the adoption of Resolutions directed towards action in Member States and instructions to the Director-General of the Organization on action by the Office, a general discussion and exchange of information and, every second year, the adoption of a biennial programme and budget for the International Labour Office.

The Governing Body is the link between the International Labour Conference of all Member States and the International Labour Office. In three meetings per year, the Governing Body executes its control over the Office by screening work progress, formulating instructions to the Director-General of the Office, adopting the output of Office activity such as Codes of Practice, monitoring and guiding financial affairs, and preparing the agendas for future International Labour Conferences. Membership of the Governing Body is subject to election for a three-year term by the three groups of Conference Representatives—governments, employers and workers. Ten government members of the Governing Body are permanent members as representatives of States of major industrial importance.

Tripartism

All the decision-making mechanisms of the ILO follow a unique structure. All decisions of Member representation are taken by the three groups of representatives, namely by the government representatives, the employers’ representatives and the workers’ representatives of each Member State. Decisions on the substance of work in the Conference Committees on International Conventions and Recommendations, in the Meeting of Experts on Codes of Practice, and in the Advisory Committees on conclusions regarding future labour conditions, are taken by members of the Committees, of which one-third represent governments, one-third represent employers and one-third represent workers. All political, financial and structural decisions are taken by the International Labour Conference (ILC) or the Governing Body, in which 50% of the voting power lies with government representatives (two per Member State in the Conference), 25% with employers’ representatives, and 25% with workers’ representatives (one for each group of a Member State in the Conference). Financial contributions to the Organization are paid solely by the governments, not by the two non-governmental groups; for this reason only governments comprise the Finance Committee.

The Conventions

The International Labour Conference has from 1919 to 1995 adopted 176 Conventions and 183 Recommendations.

Some 74 of the Conventions deal with working conditions, of which 47 are on general conditions of work and 27 are on safety and health in a narrow sense.

The subjects of the Conventions on general conditions of work are: hours of work; minimum age for admission to employment (child labour); night work; medical examination of workers; maternity protection; family responsibilities and work; and part time work. In addition, also relevant to health and safety are ILO Conventions aimed at eliminating discrimination against workers on various grounds (e.g., race, sex, disability), protecting them from unfair dismissal, and compensating them in case of occupational injury or disease.

Of the 27 Conventions on safety and health, 18 were adopted after 1960 (when decolonization led to a large increase in ILO membership) and only nine from 1919 to 1959. The most ratified Convention in this group is the Labour Inspection Convention, 1947 (No. 81), which has been ratified by more than 100 Member States of the ILO (its corollary for agriculture has been ratified by 33 countries).

High numbers of ratification can be one indicator of commitment to improving working conditions. For instance Finland, Norway and Sweden, which are famous for their safety and health record and which are the world’s showcase of safety and health practice, have ratified almost all Conventions in this field adopted after 1960.

The Labour Inspection Conventions are complemented by two further basic standards, the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155) and the Occupational Health Services Convention, 1985 (No. 161).

The Occupational Safety and Health Convention establishes the framework for a national conception of safety and health constituting a model of what the safety and health law of a country should contain. The framework directive of the EU on safety and health follows the structure and contents of the ILO Convention. The EU directive has to be transposed into national legislation by all 15 members of the EU.

The Occupational Health Services Convention deals with the operational structure within enterprises for the implementation of safety and health legislation in companies.

Several Conventions have been adopted regarding branches of economic activity or hazardous substances. These include the Safety and Health in Mines Convention, 1995 (No. 176); the Safety and Health in Construction Convention, 1988 (No. 167); the Occupational Safety and Health (Dock Work) Convention, 1979 (No. 152); the White Lead (Painting) Convention, 1921 (No. 13); the Benzene Convention, 1971 (No. 136); the Asbestos Convention, 1986 (No. 162); the Chemicals Convention, 1990 (No. 170); and the Prevention of Major Industrial Accidents Convention, 1993 (No. 174).

Associated with these norms are: the Working Environment Convention, 1977 (No. 148) (Protection of Workers against occupational Hazards in the Working Environment due to Air Pollution, Noise and Vibration); the Occupational Cancer Convention, 1974 (No. 139); and the list of occupational diseases that is part of the Employment Injury Benefits Convention, 1964 (No. 121). The last revision of the list was adopted by the Conference in 1980 and is discussed in the Chapter Workers’ Compensation, Topics in.

Other safety and health Conventions are: the Marking of Weight Convention, 1929 (No. 27); the Maximum Weight Convention, 1967 (No. 127); the Radiation Protection Convention, 1960 (No. 115); the Guarding of Machinery Convention, 1963 (No. 119); and the Hygiene (Commerce and Offices) Convention, 1964 (No. 120).

During the early period of the ILO, Recommendations were adopted instead of Conventions, such as on anthrax prevention, white phosphorus and lead poisoning. However in recent times Recommendations have tended to complement a Convention by specifying details on implementing its provisions.

Contents of Conventions on Safety and Health

Structure and content of safety and health Conventions follow a general pattern:

- scope and definitions

- obligations of governments

- consultation with organizations of workers and employers

- obligations of employers

- duties of workers

- rights of workers

- inspections

- penalties

- final provisions (on conditions for entry into force, registrations of ratifications and denunciation).

A Convention prescribes the task of government or government authorities in regulating the subject matter, highlights obligations of owners of enterprises, specifies the role of workers and their organizations through duties and rights, and closes with provisions for inspection and action against violation of the law. The Convention must of course determine its scope of application, including possible exemptions and exclusions.

Design of Conventions concerning safetyand health at work

The Preamble

Each Convention is headed by a preamble referring to the dates and the item on the agenda of the International Labour Conference; other Conventions and documents related to the topic, concerns about the subject justifying the action; underlying causes; cooperation with other international organizations such as WHO and UNEP; the form of the international instrument as a Convention or Recommendation, and the date of the adoption and citation of the Convention.

Scope

Wording of the scope is governed by flexibility towards implementation of a Convention. The guiding principle is that the Convention applies to all workers and branches of economic activity. However, in order to facilitate ratification of the Convention by all Member States, the guiding principle is often supplemented by the possibility of partial or total non-application in various fields of activity. A Member State may exclude particular branches of economic activity or particular undertakings in respect of which special problems of a substantial nature arise from the application of certain provisions or of the Convention as a whole. The scope may also foresee step by step implementation of provisions to take into account existing conditions in a country. These exclusions reflect also the availability of national resources for the implementation of new national legislation on safety and health. General conditions of exclusion are that a safe and healthy working environment is otherwise attached by alternative means and that any decision on exclusion is subject to consultation with employers and workers. The scope also includes definitions of terms used in the wording of the international instrument such as branches of economic activity, workers, workplace, employer, regulation, workers’ representative, health, hazardous chemical, major hazard installation, safety report and so forth.

Obligations of governments

Conventions on safety and health establish as a first module the task for a government to elaborate, implement and review a national policy relating to the contents of the Convention. Organizations of employers and workers must be involved in the establishment of the policy and the specification of aims and objectives. The second module concerns the enactment of laws or regulations giving effect to the provisions of the Convention and the enforcement of the law, including the employment of qualified personnel and the provision of support for the staff for inspection and advisory services. Under Articles 19 and 22 of the ILO Constitution, governments are also obliged to report regularly or on request to the International Labour Office on the practice of implementation of the Convention and Recommendation. These obligations are the basis for ILO supervisory procedures.

Consultations with organizations of employers and workers

The importance of involvement of those who are directly associated with the implementation of regulations and the consequences of accidents is undoubted. Successful safety and health practice is based on collaboration and on incorporation of opinion and good will of the persons concerned. A Convention therefore provides that the government authorities must consult employers and workers when considering the exclusion of installations from legislation for step-by-step implementation of provisions and in the development of a national policy on the subject matter of the Convention.

Obligations of employers

The responsibility for the execution of legal requirements within an enterprise lies on the owner of an enterprise or his or her representative. Legal rights on workers’ participation in the decision-making process do not alter the primary responsibility of the employer. The obligations of employers as stated in Conventions include provision of safe and healthy working procedures; the purchase of safe machinery and equipment; the use of non-hazardous substances in work processes; the monitoring and assessment of airborne chemicals at the workplace; the provision of health surveillance of workers and of first aid; the reporting of accidents and diseases to the competent authority; the training of workers; the provision of information regarding hazards related to work and their prevention; cooperation in discharging their responsibilities with workers and their representatives.

Duties of workers

Since the 1980s, Conventions have stated that workers have a duty to cooperate with their employers in the application of safety and health measures and to comply with all procedures and practices relating to safety and health at work. The duty of workers may include the reporting to supervisors of any situation which could present a special risk, or the fact that a worker has removed himself/herself from the workplace in case of imminent and serious danger to his or her life or health.

Rights of workers

A variety of special rights of workers has been stated in ILO Conventions on safety and health. In general a worker is afforded the right to information on hazardous working conditions, on the identity of chemicals used at work and on chemical safety data sheets; the right to be trained in safe working practices; the right to consultation by the employer on all aspects of safety and health associated with the work; and the right to undergo medical surveillance free of charge and with no loss of earnings. Some of these Conventions also recognize the rights of workers’ representatives, particularly regarding consultation and information. These rights are reinforced by other ILO Conventions on freedom of association, collective bargaining, workers’ representatives and protection against dismissal.

Specific articles in Conventions adopted in 1981 and later deal with the worker’s right to remove himself/herself from danger at his or her workplace. A 1993 Convention (Prevention of Major Industrial Accidents, 1993 (No. 174)) recognized the worker’s right to notify the competent authority of potential hazards which may be capable of generating a major accident.

Inspection

Conventions on safety and health express the needs for the government to provide appropriate inspection services to supervise the application of the measures taken to implement the Convention. The inspection requirement is supplemented by the obligation to provide the inspection services with the resources necessary for the accomplishment of their task.

Penalties

Conventions on safety and health often call for national regulation regarding the imposition of penalties in case of non-compliance with legal obligations. Article 9 (2) of the framework Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No 155) states: “The enforcement system shall provide for adequate penalties for violations of the laws and regulations.” These penalties may be administrative, civil or criminal in nature.

The Labour Inspection Convention, 1947 (No. 81)

The Labour Inspection Convention of 1947 (No. 81) calls on States to maintain a system of labour inspection in industrial workplaces. It fixes government obligations in regard to inspection and sets out rights, duties and powers of inspectors. This instrument is complemented by two Recommendations (Nos. 81 and 82) and by the Protocol of 1995, which extends its scope of application to the non-commercial services sector (such as the public service and state-run enterprises). The Labour Inspection (Agriculture) Convention, 1969 (No. 129), contains provisions very similar to Convention No. 81 for the agricultural sector. ILO Maritime Conventions and Recommendations also address inspection of seafarers’ working and living conditions.

The government has to establish an independent qualified corps of inspectors in sufficient number. The inspectorate must be fully equipped to provide good services. Legal provision of penalties for violation of safety and health regulations are an obligation of the government. Inspectors have the duty to enforce legal requirements, and to provide technical information and advice to employers and workers regarding effective means of complying with legal provisions.

Inspectors are to report gaps in regulations to authorities and submit annual reports on their work. Governments are called on to compile annual reports giving statistics on inspections done.

Rights and powers of inspectors are laid down, such as the right to enter workplaces and premises, to carry out examinations and tests, to initiate remedial measures, to issue orders on alteration of the installation and immediate execution. They have also the right to issue citations and institute legal proceedings in case of a violation of an employer’s duties.

The Convention contains provisions on the conduct of inspectors, such as having no financial interest in undertakings under supervision, no disclosure of trade secrets and, of particular importance, confidentiality in case of complaints by workers, which means giving no hint to the employer about the identity of complainant.

Promotion of progressive development by Conventions

Work on Conventions tries to mirror law and practice in Member States of the Organization. However, there are cases where new elements are introduced which have so far not been the subject of widespread national regulation. The initiative may come from delegates, during the discussion of a norm in a Conference Committee; where justified, it may be proposed by the Office in the first draft of a new instrument. Here are two examples:

(1)The right of a worker to remove himself or herself from work that poses an imminent and serious danger to his or her life or health.

Normally people consider that it is a natural right to leave a workplace in case of danger to life. However this action may cause damage to materials, machinery or products—and can sometimes be very costly. As installations get more sophisticated and expensive, the worker might be blamed for having unnecessarily removed himself or herself, with attempts to make him or her liable for the damage. During discussion in a Conference Committee on the Safety and Health Convention a proposal was made to protect the worker against recourse in such cases. The Conference Committee considered the proposal for hours and finally found wording to protect the worker which was acceptable to the majority of the Committee.

Article 13 of Convention No. 155 thus reads: “A worker who has removed himself from a work situation which he has reasonable justification to believe presents an imminent and serious danger to his life or health shall be protected from undue consequences in accordance with national conditions and practice”. The “undue consequences” include, of course, dismissal and disciplinary action as well as liability. Several years later, the situation was reconsidered in a new context. During the discussions at the Conference of the Construction Convention in 1987-88, the workers’ group tabled an amendment to introduce the right of a worker to remove himself or herself in case of imminent and serious danger. The proposal was finally accepted by the majority of Committee members under the condition that it was combined with a worker’s duty to immediately inform his or her supervisor about the action.

The same provision has been introduced in the Chemicals Convention, 1990 (No. 170); a similar text is included in the Safety and Health in Mines Convention, 1995 (No. 176). This means that countries which have ratified the Safety and Health Convention or the Convention on Construction, Chemical Safety or Safety and Health in Mines must provide in national law for the right of a worker to remove himself or herself and to be protected against “undue consequences”. This will probably sooner or later lead to application of this right for workers in all sectors of economic activity. This newly recognized right for workers has in the meantime been incorporated in the basic EU Directive on Safety and Health Organization of 1989; all Member States of the EU were to have incorporated the right in their legislation by the end of 1992.

(2)The right for a worker to have a medical examination instead of mandatory medical examinations.

For many years national legislation had required medical examinations for workers in special occupations as a prerequisite for assignment to or continuation of work. Over time, a long list of mandatory medical examinations before assignment and at periodic intervals had been prescribed. This well-meaning intention is increasingly turning into a burden, however, as there may be too many medical examinations administered to one person. Should the examinations be recorded in a health passport of a worker for lifelong testimony to ill-health, as practised in some countries, the medical examination in the end could become a tool for selection into unemployment. A young worker having recorded a long list of medical examinations in his or her life due to exposure to hazardous substances may not find an employer ready to give him or her a job. The doubt may be too strong that this worker may sooner or later be absent too often because of illness.

A second consideration has been that any medical examination is an intrusion into a person’s private life and therefore a worker should be the one to decide on medical procedures.

The International Labour Office proposed, therefore, to introduce in the Night Work Convention, 1990 (No. 171) the right of a worker to have a medical examination instead of calling for mandatory surveillance. This idea won broad support and was finally reflected in Article 4 of the Night Work Convention by the International Labour Conference in 1990, which reads:

1.At their request, workers shall have the right to undergo a health assessment without charge and to receive advice on how to reduce or avoid health problems associated with their work: (a) before taking up an assignment as a night worker; (b) at regular intervals during such an assignment; (c) if they experience health problems during such an assignment which are not caused by factors other than the performance of the night work.

2.With the exception of a finding of unfitness for night work, the findings of such assessments shall not be transmitted to others without the worker’s consent and shall not be used to their detriment.

It is difficult for many health professionals to follow this new conception. However, they should realize that a person’s right to determine whether to undergo a medical examination is an expression of contemporary notions of human rights. The provision has been already taken up by national legislation, for example in the 1994 Act on Working Time in Germany, which makes reference to the Convention. And more importantly, the EU Framework Directive on Safety and Health follows this model in its provisions on health surveillance.

Functions of the International Labour Office

The functions of the International Labour Office as laid down in Article 10 of the Constitution include the collection and distribution of information on all subjects related to the international adjustment of conditions of industrial life and labour with special emphasis on future international labour standards, the preparation of documents on the various items of the agenda for the meeting of the ILC (especially the preparatory work on contents and wording of Conventions and Recommendations), the provision of advisory services to governments, employers’ organizations and workers’ organizations of member states related to labour legislation and administrative practice, including systems of inspection, and the edition and dissemination of publications of international interest dealing with problems of industry and employment.

Like any ministry of labour, the International Labour Office is made up of bureaus, departments and branches concerned with the various fields of labour policy. Two special institutes were established to support the Office and Member States: the International Institute for Labour Studies at ILO headquarters, and the International Training Centre of the ILO in Turin, Italy.

A Director-General, elected by the Governing Body for a five-year term, and three Deputy Director-Generals, appointed by the Director-General, govern (as of 1996) 13 departments; 11 bureaus at headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland; two liaison offices with international organizations; five regional departments, in Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific, the Arab States, and Europe, with 35 area and branch offices and 13 multi-disciplinary teams (a group of professionals of various disciplines who provide advisory services in Member States of a subregion).

The Working Conditions and Environment Department is the Department in which the bulk of safety and health work is carried out. It comprises a staff of about 70 professionals and general service personnel of 25 nationalities, including professional experts in the multi-disciplinary teams. As of 1996, it has two branches: the Conditions of Work and Welfare Facilities Branch (CONDI/T) and the Occupational Safety and Health Branch (SEC/HYG).

The Safety and Health Information Services Section of SEC/HYG maintains the International Occupational Safety and Health Information Centre (CIS) and the Occupational Safety and Health Information Support Systems Section. The work on this edition of the Encyclopaedia is housed in the Support Systems Section.

A special unit of the Department was established in 1991: the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC). The new programme executes, jointly with Member States in all regions of the world, national programmes of activity against child labour. The programme is financed by special contributions of several Member States, such as Germany, Spain, Australia, Belgium, the United States, France and Norway.

In addition, in the course of the review of the ILO’s major safety and health programme established in the 1970s, the International Programme for the Improvement of Working Conditions and the Environment—known under its French acronym PIACT—the International Labour Conference adopted in 1984 the PIACT Resolution. In principle, the Resolution constitutes a framework of operation for all action by the ILO and by Member States of the Organization in the field of safety and health:

- Work should take place in a safe and healthy working environment.

- Conditions of work should be consistent with workers’ well-being and human dignity.

- Work should offer real possibilities for personal achievement, self-fulfilment, and service to society.

Publications concerning workers’ health are published in the Occupational Safety and Health Series, such as Occupational Exposure Limits for Airborne Toxic Substances, a listing of national exposure limits of 15 Member States; or the International Directory of Occupational Safety and Health Services and Institutions, which compiles information on the safety and health administrations of Member States; or Protection of Workers from Power Frequency Electric and Magnetic Fields, a practical guide to provide information on the possible effects of electric and magnetic fields on human health and on procedures for higher standards of safety.

Typical products of the safety and health work of the ILO are the codes of practice, which constitute a kind of model set of regulations on safety and health in many fields of industrial work. These codes are often elaborated in order to facilitate the ratification and application of ILO Conventions. For example, the Code of Practice on Prevention of Major Industrial Accidents, whose objective is to provide guidance in the setting up of an administrative, legal and technical system for the control of major hazard installations in order to avoid major disasters. The Code of Practice on Recording and Notification of Occupational Accidents and Diseases aims at a harmonized practice in the collection of data and the establishment of statistics on accidents and diseases and associated events and circumstances in order to stimulate preventive action and to facilitate comparative work between Member States (these are just two examples from a long list). Within the field of information exchange two major events are organized by the Safety and Health Branch of the ILO: the World Congress on Occupational Safety and Health, and the ILO International Pneumoconiosis Conference (which is now called The International Conference on Occupational Respiratory Diseases).