Children categories

94. Education and Training Services (7)

94. Education and Training Services

Chapter Editor: Michael McCann

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Diseases affecting day-care workers & teachers

2. Hazards & precautions for particular classes

3. Summary of hazards in colleges & universities

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

95. Emergency and Security Services (9)

95. Emergency and Security Services

Chapter Editor: Tee L. Guidotti

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Recommendations & criteria for compensation

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

96. Entertainment and the Arts (31)

96. Entertainment and the Arts

Chapter Editor: Michael McCann

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Arts and Crafts

Performing and Media Arts

Entertainment

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Precautions associated with hazards

2. Hazards of art techniques

3. Hazards of common stones

4. Main risks associated with sculpture material

5. Description of fibre & textile crafts

6. Description of fibre & textile processes

7. Ingredients of ceramic bodies & glazes

8. Hazards & precautions of collection management

9. Hazards of collection objects

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see the figure in the article context.

97. Health Care Facilities and Services (25)

97. Health Care Facilities and Services

Chapter Editor: Annelee Yassi

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Health Care: Its Nature and Its Occupational Health Problems

Annalee Yassi and Leon J. Warshaw

Social Services

Susan Nobel

Home Care Workers: The New York City Experience

Lenora Colbert

Occupational Health and Safety Practice: The Russian Experience

Valery P. Kaptsov and Lyudmila P. Korotich

Ergonomics and Health Care

Hospital Ergonomics: A Review

Madeleine R. Estryn-Béhar

Strain in Health Care Work

Madeleine R. Estryn-Béhar

Case Study: Human Error and Critical Tasks: Approaches for Improved System Performance

Work Schedules and Night Work in Health Care

Madeleine R. Estryn-Béhar

The Physical Environment and Health Care

Exposure to Physical Agents

Robert M. Lewy

Ergonomics of the Physical Work Environment

Madeleine R. Estryn-Béhar

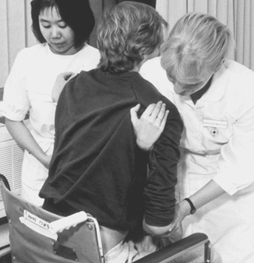

Prevention and Management of Back Pain in Nurses

Ulrich Stössel

Case Study: Treatment of Back Pain

Leon J. Warshaw

Health Care Workers and Infectious Disease

Overview of Infectious Diseases

Friedrich Hofmann

Prevention of Occupational Transmission of Bloodborne Pathogens

Linda S. Martin, Robert J. Mullan and David M. Bell

Tuberculosis Prevention, Control and Surveillance

Robert J. Mullan

Chemicals in the Health Care Environment

Overview of Chemical Hazards in Health Care

Jeanne Mager Stellman

Managing Chemical Hazards in Hospitals

Annalee Yassi

Waste Anaesthetic Gases

Xavier Guardino Solá

Health Care Workers and Latex Allergy

Leon J. Warshaw

The Hospital Environment

Buildings for Health Care Facilities

Cesare Catananti, Gianfranco Damiani and Giovanni Capelli

Hospitals: Environmental and Public Health Issues

M.P. Arias

Hospital Waste Management

M.P. Arias

Managing Hazardous Waste Disposal Under ISO 14000

Jerry Spiegel and John Reimer

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Examples of health care functions

2. 1995 integrated sound levels

3. Ergonomic noise reduction options

4. Total number of injuries (one hospital)

5. Distribution of nurses’ time

6. Number of separate nursing tasks

7. Distribution of nurses' time

8. Cognitive & affective strain & burn-out

9. Prevalence of work complaints by shift

10. Congenital abnormalities following rubella

11. Indications for vaccinations

12. Post-exposure prophylaxis

13. US Public Health Service recommendations

14. Chemicals’ categories used in health care

15. Chemicals cited HSDB

16. Properties of inhaled anaesthetics

17. Choice of materials: criteria & variables

18. Ventilation requirements

19. Infectious diseases & Group III wastes

20. HSC EMS documentation hierarchy

21. Role & responsibilities

22. Process inputs

23. List of activities

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see the figure in the article context.

98. Hotels and Restaurants (4)

98. Hotels and Restaurants

Chapter Editor: Pam Tau Lee

Table of Contents

99. Office and Retail Trades (7)

99. Office and Retail Trades

Chapter Editor: Jonathan Rosen

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

The Nature of Office and Clerical Work

Charles Levenstein, Beth Rosenberg and Ninica Howard

Professionals and Managers

Nona McQuay

Offices: A Hazard Summary

Wendy Hord

Bank Teller Safety: The Situation in Germany

Manfred Fischer

Telework

Jamie Tessler

The Retail Industry

Adrienne Markowitz

Case Study: Outdoor Markets

John G. Rodwan, Jr.

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Standard professional jobs

2. Standard clerical jobs

3. Indoor air pollutants in office buildings

4. Labour statistics in the retail industry

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

100. Personal and Community Services (6)

100. Personal and Community Services

Chapter Editor: Angela Babin

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Indoor Cleaning Services

Karen Messing

Barbering and Cosmetology

Laura Stock and James Cone

Laundries, Garment and Dry Cleaning

Gary S. Earnest, Lynda M. Ewers and Avima M. Ruder

Funeral Services

Mary O. Brophy and Jonathan T. Haney

Domestic Workers

Angela Babin

Case Study: Environmental Issues

Michael McCann

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Postures observed during dusting in a hospital

2. Dangerous chemicals used in cleaning

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

101. Public and Government Services (12)

101. Public and Government Services

Chapter Editor: David LeGrande

Table of Contents

Tables and Figurs

Occupational Health and Safety Hazards in Public and Governmental Services

David LeGrande

Case Report: Violence and Urban Park Rangers in Ireland

Daniel Murphy

Inspection Services

Jonathan Rosen

Postal Services

Roxanne Cabral

Telecommunications

David LeGrande

Hazards in Sewage (Waste) Treatment Plants

Mary O. Brophy

Domestic Waste Collection

Madeleine Bourdouxhe

Street Cleaning

J.C. Gunther, Jr.

Sewage Treatment

M. Agamennone

Municipal Recycling Industry

David E. Malter

Waste Disposal Operations

James W. Platner

The Generation and Transport of Hazardous Wastes: Social and Ethical Issues

Colin L. Soskolne

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Hazards of inspection services

2. Hazardous objects found in domestic waste

3. Accidents in domestic waste collection (Canada)

4. Injuries in the recycling industry

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

102. Transport Industry and Warehousing (18)

102. Transport Industry and Warehousing

Chapter Editor: LaMont Byrd

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

General Profile

LaMont Byrd

Case Study: Challenges to Workers’ Health and Safety in the Transportation and Warehousing Industry

Leon J. Warshaw

Air Transport

Airport and Flight Control Operations

Christine Proctor, Edward A. Olmsted and E. Evrard

Case Studies of Air Traffic Controllers in the United States and Italy

Paul A. Landsbergis

Aircraft Maintenance Operations

Buck Cameron

Aircraft Flight Operations

Nancy Garcia and H. Gartmann

Aerospace Medicine: Effects of Gravity, Acceleration and Microgravity in the Aerospace Environment

Relford Patterson and Russell B. Rayman

Helicopters

David L. Huntzinger

Road Transport

Truck and Bus Driving

Bruce A. Millies

Ergonomics of Bus Driving

Alfons Grösbrink and Andreas Mahr

Motor Vehicle Fuelling and Servicing Operations

Richard S. Kraus

Case Study: Violence in Gasoline Stations

Leon J. Warshaw

Rail Transport

Rail Operations

Neil McManus

Case Study: Subways

George J. McDonald

Water Transport

Water Transportation and the Maritime Industries

Timothy J. Ungs and Michael Adess

Storage

Storage and Transportation of Crude Oil, Natural Gas, Liquid Petroleum Products and Other Chemicals

Richard S. Kraus

Warehousing

John Lund

Case Study: US NIOSH Studies of Injuries among Grocery Order Selectors

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Bus driver seat measurements

2. Illumination levels for service stations

3. Hazardous conditions & administration

4. Hazardous conditions & maintenance

5. Hazardous conditions & right of way

6. Hazard control in the Railway industry

7. Merchant vessel types

8. Health hazards common across vessel types

9. Notable hazards for specific vessel types

10. Vessel hazard control & risk-reduction

11. Typical approximate combustion properties

12. Comparison of compressed & liquified gas

13. Hazards involving order selectors

14. Job safety analysis: Fork-lift operator

15. Job safety analysis: Order selector

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Overview of Infectious Diseases

Infectious diseases play a significant part in worldwide occurrences of occupational disease in HCWs. Since reporting procedures vary from country to country, and since diseases considered job-related in one country may be classified as non-occupational elsewhere, accurate data concerning their frequency and their proportion of the overall number of occupational diseases among HCWs are difficult to obtain. The proportions range from about 10% in Sweden (Lagerlöf and Broberg 1989), to about 33% in Germany (BGW 1993) and nearly 40% in France (Estryn-Béhar 1991).

The prevalence of infectious diseases is directly related to the efficacy of preventive measures such as vaccines and post-exposure prophylaxis. For example, during the 1980s in France, the proportion of all viral hepatitides fell to 12.7% of its original level thanks to the introduction of vaccination against hepatitis B (Estryn-Béhar 1991). This was noted even before hepatitis A vaccine became available.

Similarly, it may be presumed that, with the declining immunization rates in many countries (e.g., in the Russian Federation and Ukraine in the former Soviet Union during 1994-1995), cases of diphtheria and poliomyelitis among HCWs will increase.

Finally, occasional infections with streptococci, staphylococci and Salmonella typhi are being reported among health care workers.

Epidemiological Studies

The following infectious diseases—listed in order of frequency—are the most important in worldwide occurrences of occupational infectious diseases in health care workers:

- hepatitis B

- tuberculosis

- hepatitis C

- hepatitis A

- hepatitis, non A-E.

Also important are the following (not in order of frequency):

- varicella

- measles

- mumps

- rubella

- Ringelröteln (parvovirus B 19 virus infections)

- HIV/AIDS

- hepatitis D

- EBV hepatitis

- CMV hepatitis.

It is very doubtful that the very many cases of enteric infection (e.g., salmonella, shigella, etc.) often included in the statistics are, in fact, job-related, since these infections are transmitted faecally/orally as a rule.

Much data is available concerning the epidemiological significance of these job-related infections mostly in relation to hepatitis B and its prevention but also in relation to tuberculosis, hepatitis A and hepatitis C. Epidemiological studies have also dealt with measles, mumps, rubella, varicella and Ringenröteln. In using them, however, care must be taken to distinguish between incidence studies (e.g., determination of annual hepatitis B infection rates), sero-epidemiological prevalence studies and other types of prevalence studies (e.g., tuberculin tests).

Hepatitis B

The risk of hepatitis B infections, which are primarily transmitted through contact with blood during needlestick injuries, among HCWs, depends on the frequency of this disease in the population they serve. In northern, central and western Europe, Australia and North America it is found in about 2% of the population. It is encountered in about 7% of the population in southern and south-eastern Europe and most parts of Asia. In Africa, the northern parts of South America and in eastern and south-eastern Asia, rates as high as 20% have been observed (Hollinger 1990).

A Belgian study found that 500 HCWs in northern Europe became infected with hepatitis B each year while the figure for southern Europe was 5,000 (Van Damme and Tormanns 1993). The authors calculated that the annual case rate for western Europe is about 18,200 health care workers. Of these, about 2,275 ultimately develop chronic hepatitis, of whom some 220 will develop cirrhosis of the liver and 44 will develop hepatic carcinoma.

A large study involving 4,218 HCWs in Germany, where about 1% of the population is positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), found that the risk of contracting hepatitis B is approximately 2.5 greater among HCWs than in the general population (Hofmann and Berthold 1989). The largest study to date, involving 85,985 HCWs worldwide, demonstrated that those in dialysis, anaesthesiology and dermatology departments were at greatest risk of hepatitis B (Maruna 1990).

A commonly overlooked source of concern is the HCW who has a chronic hepatitis B infection. More than 100 instances have been recorded worldwide in which the source of the infection was not the patient but the doctor. The most spectacular instance was the Swiss doctor who infected 41 patients (Grob et al. 1987).

While the most important mechanism for transmitting the hepatitis B virus is an injury by a blood-contaminated needle (Hofmann and Berthold 1989), the virus has been detected in a number of other body fluids (e.g., male semen, vaginal secretions, cerebrospinal fluid and pleural exudate) (CDC 1989).

Tuberculosis

In most countries around the world, tuberculosis continues to rank first or second in importance of work-related infections among HCWs (see the article “Tuberculosis prevention, control and surveillance”). Many studies have demonstrated that although the risk is present throughout the professional life, it is greatest during the period of training. For example, a Canadian study in the 1970s demonstrated the tuberculosis rate among female nurses to be double that of women in other professions (Burhill et al. 1985). And, in Germany, where the tuberculosis incidence ranges around 18 per 100,000 for the general population, it is about 26 per 100,000 among health care workers (BGW 1993).

A more accurate estimate of the risk of tuberculosis may be obtained from epidemiological studies based on the tuberculin test. A positive reaction is an indicator of infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or other mycobacteria or a prior inoculation with the BCG vaccine. If that inoculation was received 20 or more years earlier, it is presumed that the positive test indicates at least one contact with tubercle bacilli.

Today, tuberculin testing is done by means of the patch test in which the response is read within five to seven days after the application of the “stamp”. A large-scale German study based on such skin tests showed a rate of positives among health professionals that was only moderately higher than that among the general population (Hofmann et al. 1993), but long-range studies demonstrate that a greatly heightened risk of tuberculosis does exist in some areas of health care services.

More recently, anxiety has been generated by the increasing number of cases infected with drug-resistant organisms. This is a matter of particular concern in designing a prophylactic regimen for apparently healthy health care workers whose tuberculin tests “converted” to positive after exposure to patients with tuberculosis.

Hepatitis A

Since the hepatitis A virus is transmitted almost exclusively through faeces, the number of HCWs at risk is substantially smaller than for hepatitis B. An early study conducted in West Berlin showed that paediatric personnel were at greatest risk of this infection (Lange and Masihi 1986). These results were subsequently confirmed by a similar study in Belgium (Van Damme et al. 1989). Similarly, studies in Southwest Germany showed increase risk to nurses, paediatric nurses and cleaning women (Hofmann et al. 1992; Hofmann, Berthold and Wehrle 1992). A study undertaken in Cologne, Germany, revealed no risk to geriatric nurses in contrast to higher prevalence rates among the personnel of child care centres. Another study showed increased risk of hepatitis A among paediatric nurses in Ireland, Germany and France; in the last of these, greater risk was found in workers in psychiatric units treating children and youngsters. Finally, a study of infection rates among handicapped people disclosed higher levels of risk for the patients as well as the workers caring for them (Clemens et al. 1992).

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C, discovered in 1989, like hepatitis B, is primarily transmitted through blood introduced via needle puncture wounds. Until recently, however, data relating to its threat to HCWs have been limited. A 1991 New York study of 456 dentists and 723 controls showed an infection rate of 1.75% among the dentists compared with 0.14% among the controls (Klein et al. 1991). A German research group demonstrated the prevalence of hepatitis C in prisons and attributed it to the large number of intravenous drug users among the inmates (Gaube et al. 1993). An Austrian study found 2.0% of 294 health care personnel to be seropositive for hepatitis C antibodies, a figure thought to be much higher than that among the general population (Hofmann and Kunz 1990). This was confirmed by another study of HCWs conducted in Cologne, Germany (Chriske and Rossa 1991).

A study in Freiburg, Germany, found that contact with handicapped residents of nursing homes, particularly those with infantile cerebral paresis and trisomia-21, patients with haemophilia and those dependent on drugs administered intravenously presented a particular risk of hepatitis C to workers involved in their care. A significantly increased prevalence rate was found in dialysis personnel and the relative risk to all health care workers was estimated to be 2.5% (admittedly calculated from a relatively small sample).

A possible alternative path of infection was demonstrated in 1993 when a case of hepatitis C was shown to have developed after a splash into the eye (Sartori et al. 1993).

Varicella

Studies of the prevalence of varicella, an illness particularly grave in adults, have consisted of tests for varicella antibodies (anti VZV) conducted in Anglo-Saxon countries. Thus, a seronegative rate of 2.9% was found among 241 hospital employees aged 24 to 62, but the rate was 7.5% for those under the age of 35 (McKinney, Horowitz and Baxtiola 1989). Another study in a paediatric clinic yielded a negative rate of 5% among 2,730 individuals tested in the clinic, but these data become less impressive when it is noted that the serological tests were performed only on persons without a history of having had varicella. A significantly increased risk of varicella infection for paediatric hospital personnel, however, was demonstrated by a study conducted in Freiburg, which found that, in a group of 533 individuals working in hospital care, paediatric hospital care and administration, evidence of varicella immunity was present in 85% of persons younger than 20 years.

Mumps

In considering risk levels of mumps infection, a distinction must be made between countries in which mumps immunization is mandatory and those in which these inoculations are voluntary. In the former, nearly all children and young people will have been immunized and, therefore, mumps poses little risk to health care workers. In the latter, which includes Germany, cases of mumps are becoming more frequent. As a result of lack of immunity, the complications of mumps have been increasing, particularly among adults. A report of an epidemic in a non-immune Inuit population on St. Laurance Island (located between Siberia and Alaska) demonstrated the frequency of such complications of mumps as orchitis in men, mastitis in women and pancreatitis in both sexes (Philip, Reinhard and Lackman 1959).

Unfortunately, epidemiological data on mumps among HCWs are very sparse. A 1986 study in Germany showed that the rate of mumps immunity among 15 to 10 year-olds was 84% but, with voluntary rather than mandatory inoculation, one may presume that this rate has been declining. A 1994 study involving 774 individuals in Freiburg indicated a significantly increased risk to employees in paediatric hospitals (Hofmann, Sydow and Michaelis 1994).

Measles

The situation with measles is similar to that with mumps. Reflecting its high degree of contagiousness, risks of infection among adults emerge as their immunization rates fall. A US study reported an immunity rate of over 99% (Chou, Weil and Arnmow 1986) and two years later 98% of a cohort of 163 nursing students were found to have immunity (Wigand and Grenner 1988). A study in Freiburg yielded rates of 96 to 98% among nurses and paediatric nurses while the rates of immunity among non-medical personnel were only 87 to 90% (Sydow and Hofman 1994). Such data would support a recommendation that immunization be made mandatory for the general population.

Rubella

Rubella falls between measles and mumps with respect to its contagiousness. Studies have shown that about 10% of HCWs are not immune (Ehrengut and Klett 1981; Sydow and Hofmann 1994) and, therefore, at high risk of infection when exposed. Although generally not a serious illness among adults, rubella may be responsible for devastating effects on the foetus during the first 18 weeks of pregnancy: abortion, stillbirth or congenital defects (see table 1) (South, Sever and Teratogen 1985; Miller, Vurdien and Farrington 1993). Since these may be produced even before the woman knows that she is pregnant and, since health care workers, particularly those in contact with paediatric patients, are likely to be exposed, it is especially important that inoculation be urged (and perhaps even required) for all female health care workers of child-bearing age who are not immune.

Table 1. Congenital abnormalities following rubella infection in pregnancy

|

Studies by South, Sever and Teratogen (1985) |

|||||

|

Week of pregnancy |

<4 |

5–8 |

9–12 |

13–16 |

>17 |

|

Deformity rate (%) |

70 |

40 |

25 |

40 |

8 |

|

Studies by Miller, Vurdien and Farrington (1993) |

|||||

|

Week of pregnancy |

<10 |

11–12 |

13–14 |

15–16 |

>17 |

|

Deformity rate (%) |

90 |

33 |

11 |

24 |

0 |

HIV/AIDS

During the 1980s and 1990s, HIV seroconversions (i.e., a positive reaction in an individual previously found to have been negative) became a minor occupational risk among HCWs, although clearly not one to be ignored. By early 1994, reports of some 24 reliably documented cases and 35 possible cases were collected in Europe (Pérez et al. 1994) with an additional 43 documented cases and 43 possible cases were reported in the US (CDC 1994a). Unfortunately, except for avoiding needlesticks and other contacts with infected blood or body fluids, there are no effective preventive measures. Some prophylactic regimens for individuals who have been exposed are recommended and described in the article “Prevention of occupational transmission of bloodborne pathogens”.

Other infectious diseases

The other infectious diseases listed earlier in this article have not yet emerged as significant hazards to HCWs either because they have not been recognized and reported or because their epidemiology has not yet been studied. Sporadic reports of single and small clusters of cases suggest that the identification and testing of serological markers should be explored. For example, a 33-month study of typhus conducted by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) revealed that 11.2% of all sporadic cases not associated with outbreaks occurred in laboratory workers who had examined stool specimens (Blazer et al. 1980).

The future is clouded by two simultaneous problems: the emergence of new pathogens (e.g., new strains such as hepatitis G and new organisms such as the Ebola virus and the equine morbillivirus recently discovered to be fatal to both horses and humans in Australia) and the continuing development of drug resistance by well-recognized organisms such as the tuberculus bacillus. HCWs are likely to be the first to be systematically exposed. This makes their prompt and accurate identification and the epidemiological study of their patterns of susceptibility and transmission of the utmost importance.

Prevention of Infectious Diseases among Health Care Workers

The first essential in the prevention of infectious disease is the indoctrination of all HCWs, support staff as well as health professionals, in the fact that health care facilities are “hotbeds” of infection with every patient representing a potential risk. This is important not only for those directly involved in diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, but also those who collect and handle blood, faeces and other biological materials and those who come in contact with dressings, linens, dishes and other fomites. In some instances, even breathing the same air may be a possible hazard. Each health care facility, therefore, must develop a detailed procedure manual identifying these potential risks and the steps needed to eliminate, avoid or control them. Then, all personnel must be drilled in following these procedures and monitored to ensure that they are being properly performed. Finally, all failures of these protective measures must be recorded and reported so that revision and/or retraining may be undertaken.

Important secondary measures are the labelling of areas and materials which may be especially infectious and the provision of gloves, gowns, masks, forceps and other protective equipment. Washing the hands with germicidal soap and running water (wherever possible) will not only protect the health care worker but also will minimize the risk of his or her transmitting the infection to co-workers and other patients.

All blood and body fluid specimens or splashes and materials stained with them must be handled as though they are infected. The use of rigid plastic containers for the disposal of needles and other sharp instruments and diligence in the proper disposal of potentially infectious wastes are important preventive measures.

Careful medical histories, serological testing and patch testing should be performed prior to or as soon as health care workers report for duty. Where advisable (and there are no contraindications), appropriate vaccines should be administered (hepatitis B, hepatitis A and rubella appear to be the most important) (see table 2). In any case, seroconversion may indicate an acquired infection and the advisability of prophylactic treatment.

Table 2. Indications for vaccinations in health service employees.

|

Disease |

Complications |

Who should be vaccinated? |

|

Diptheria |

In the event of an epidemic, all employees without |

|

|

Hepatitis A |

Employees in the paediatric field as well as in infection |

|

|

Hepatitis B |

All seronegative employees with possibility of contact |

|

|

Influenza |

Regularly offered to all employees |

|

|

Measles |

Encephalitis |

Seronegative employees in the paediatric field |

|

Mumps |

Meningitis |

Seronegative employees in the paediatric field |

|

Rubella |

Embryopathy |

Seronegative employees in paediatry/midwifery/ |

|

Poliomyelitis |

All employees, e.g., those involved in vaccination |

|

|

Tetanus |

Employees in gardening and technical fields obligatory, |

|

|

Tuberculosis |

In all events employees in pulmonology and lung surgery |

|

|

Varicellas |

Foetal risks |

Seronegative employees in paediatry or at least in the |

Prophylactic therapy

In some exposures when it is known that the worker is not immune and has been exposed to a proven or highly suspected risk of infection, prophylactic therapy may be instituted. Especially if the worker presents any evidence of possible immunodeficiency, human immunoglobulin may be administered. Where specific “hyperimmune” serum is available, as in mumps and hepatitis B, it is preferable. In infections which, like hepatitis B, may be slow to develop, or “booster” doses are advisable, as in tetanus, a vaccine may be administered. When vaccines are not available, as in meningococcus infections and plague, prophylactic antibiotics may be used either alone or as a supplement to immune globulin. Prophylactic regimens of other drugs have been developed for tuberculosis and, more recently, for potential HIV infections, as discussed elsewhere in this chapter.

Rail Operations

Railroads provide a major mode of transportation around the world. Today, even with competition from road and airborne transport, rail remains an important means of land-based movement of bulk quantities of goods and materials. Railroad operations are carried out in an enormously wide variety of terrains and climates, from Arctic permafrost to equatorial jungle, from rainforest to desert. The roadbed of partly crushed stone (ballast) and track consisting of steel rails and ties of wood, concrete or steel are common to all railroads. Ties and ballast maintain the position of the rails.

The source of power used in railroad operations worldwide (steam, diesel-electric and current electricity) spans the history of development of this mode of transportation.

Administration and Train Operations

Administration and train operations create the public profile of the railroad industry. They ensure that goods move from origin to destination. Administration includes office personnel involved in business and technical functions and management. Train operations include dispatchers, rail traffic control, signal maintainers, train crews and yard workers.

Dispatchers ensure that a crew is available at the appropriate point and time. Railroads operate 24 hours per day, 7 days per week throughout the year. Rail traffic control personnel coordinate train movements. Rail traffic control is responsible for assigning track to trains in the appropriate sequence and time. This function is complicated by single sets of track that must be shared by trains moving in both directions. Since only one train can occupy a particular section of track at any time, rail traffic control must assign occupancy of the main line and sidings, in a manner that assures safety and minimizes delay.

Signals provide visual cues to train operators, as well as to drivers of road vehicles at level train crossings. For train operators, signals must provide unambiguous messages about the status of the track ahead. Signals today are used as an adjunct to rail traffic control, the latter being conducted by radio on channels received by all operating units. Signal maintainers must ensure operation of these units at all times, which can sometimes involve working alone in remote areas in all weather at any time, day or night.

Yard workers’ duties include ensuring that the rolling stock is prepared to receive cargo, which is an increasingly important function in this era of quality management. Tri-level automobile transporter cars, for example, must be cleaned prior to use and readied to accept vehicles by moving chocks to appropriate positions. The distance between levels in these cars is too short for the average male to stand upright, so that work is done in a hunched over position. Similarly, the handholds on some cars force yard workers to assume an awkward posture during shunting operations.

For long runs, a train crew operates the train between designated transfer points. A replacement crew takes over at the transfer point and continues the journey. The first crew must wait at the transfer point for another train to make the return trip. The combined trips and the wait for the return train can consume many hours.

A train trip on single track can be very fragmented, in part because of problems in scheduling, track work and the breakdown of equipment. Occasionally a crew returns home in the cab of a trailing locomotive, in the caboose (where still in use) or even by taxi or bus.

The train crew’s duties may include dropping off some cars or picking up additional ones en route. This could occur at any hour of the day or night under any imaginable weather conditions. The assembly and disassembly of trains are the sole duties of some train crews in yards.

On occasion there is a failure of one of the knuckles that couple cars together or a break in a hose that carries braking system air between cars. This necessitates investigative work by one of the train crew and repair or replacement of the defective part. The spare knuckle (about 30 kg) must be carried along the roadbed to the repair point, and the original removed and replaced. Work between cars must reflect careful planning and preparation to ensure that the train does not move during the procedure.

In mountainous areas, breakdown may occur in a tunnel. The locomotive must maintain power above idle under these conditions in order to keep the braking functional and to prevent train runaway. Running the engine in a tunnel could cause the tunnel to fill with exhaust gases (nitrogen dioxide, nitric oxide, carbon monoxide and sulphur dioxide).

Table 1 summarizes potential hazardous conditions associated with administration and train operations.

Table 1. Hazardous conditions associated with administration and train operations.

|

Conditions |

Affected groups |

Comments |

|

Exhaust emissions |

Train crew, supervisors, technical advisors |

Emissions primarily include nitrogen dioxide, nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide and particulates containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Potential for exposure is most likely in unventilated tunnels. |

|

Noise |

Train crew, supervisors, technical advisors |

In-cab noise could exceed regulated limits. |

|

Whole-body vibration |

Train crew |

Structure-borne vibration transmitted through the floor and seats in the cab originates from the engine and motion along the track and over gaps between rails. |

|

Electromagnetic fields |

Train crew, signal maintainers |

AC and DC fields are possible, depending on design of power unit and traction motors. |

|

Radio-frequency fields |

Users of two-way radios |

Effects on humans are not fully established. |

|

Weather |

Train crew, yard workers, signal maintainers |

Ultraviolet energy can cause sunburn, skin cancer and cataracts. Cold can cause cold stress and frostbite. Heat can cause heat stress. |

|

Shiftwork |

Dispatchers, rail traffic control, train crews, signal maintainers |

Train crews can work irregular hours; remuneration is often based on travelling a fixed distance within a time period. |

|

Musculoskeletal injury |

Train crew, yard workers |

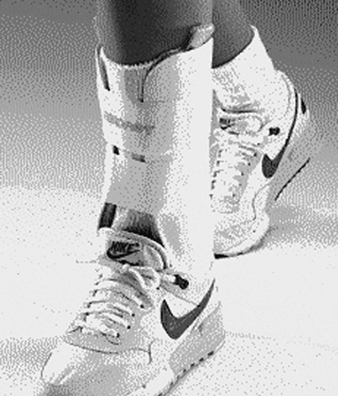

Ankle injury can occur during disembarkment from moving equipment. Shoulder injury can occur during embarkment onto moving equipment. Injury can occur at various sites while carrying knuckles on rough terrain. Work is performed in awkward postures. |

|

Video displays units |

Management, administrative and technical staff, dispatchers, rail traffic control |

Effective use of computerized workstations depends on application of visual and office ergonomic principles. |

|

Rundown accidents |

All workers |

Rundown can occur when the individual stands on an active track and fails to hear approach of trains, track equipment and moving cars. |

Maintenance of Rolling Stock and Track Equipment

Rolling stock includes locomotives and railcars. Track equipment is specialized equipment used for track patrol and maintenance, construction and rehabilitation. Depending on the size of the railroad, maintenance can range from onsite (small-scale repairs) to complete stripdown and rebuilding. Rolling stock must not fail in operation, since failure carries serious adverse safety, environmental and business consequences. If a car carries a hazardous commodity, the consequences that can arise from failure to find and repair a mechanical defect can be enormous.

Larger rail operations have running shops and centralized stripdown and rebuild facilities. Rolling stock is inspected and prepared for the trip at running shops. Minor repair is performed on both cars and locomotives.

Railcars are rigid structures that have pivot points near each end. The pivot point accepts a vertical pin located in the truck (the wheels and their support structure). The body of the car is lifted from the truck for repairs. Minor repair can involve the body of the car or attachments or brakes or other parts of the truck. Wheels may require machining on a lathe to remove flat spots.

Major repair could include removal and replacement of damaged or corroded metal sheeting or frame and abrasive blasting and repainting. It could also include removal and replacement of wooden flooring. Trucks, including wheel-axle sets and bearings, may require disassembly and rebuilding. Rehabilitation of truck castings involves build-up welding and grinding. Rebuilt wheel-axle sets require machining to true the assembly.

Locomotives are cleaned and inspected prior to each trip. The locomotive may also require mechanical service. Minor repairs include oil changes, work on brakes and servicing of the diesel engine. Removal of a truck for wheel truing or evening may also be needed. Operation of the engine may be required in order to position the locomotive inside the service building or to remove it from the building. Prior to re-entry into service the locomotive could require a load test, during which the engine is operated at full throttle. Mechanics work in close proximity to the engine during this procedure.

Major servicing could involve complete stripdown of the locomotive. The diesel engine and engine compartment, compressor, generator and traction motors require thorough degreasing and cleaning owing to heavy service and contact of fuel and lubricants with hot surfaces. Individual components may then be stripped and rebuilt.

Traction motor casings may require build-up welding. Armatures and rotors may need machining in order to remove old insulation, then be repaired and impregnated with a solution of varnish.

Track maintenance equipment includes trucks and other equipment that can operate on road and rail, as well as specialized equipment that operates only on rail. The work may include highly specialized units, such as track inspection units or rail-grinding machines, which may be “one of a kind”, even in large railroad companies. Track maintenance equipment may be serviced in garage settings or in field locations. The engines in this equipment may produce considerable exhaust emissions due to long periods between service and lack of familiarity of mechanics. This can have major pollution consequences during operation in confined spaces, such as tunnels and sheds and enclosing formations.

Table 2 summarizes potential hazardous conditions associated with maintenance of rolling stock and track equipment as well as transportation accidents.

Table 2. Hazardous conditions associated with maintenance and transportation accidents.

|

Conditions |

Affected groups |

Comments |

|

Skin contamination with waste oils and lubricants |

Diesel mechanics, traction motor mechanics |

Decomposition of hydrocarbons in contact with hot surfaces can produce polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). |

|

Exhaust emissions |

All workers in diesel shop, wash facility, refuelling area, load test area |

Emissions primarily include nitrogen dioxide, nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide and particulates containing (PAHs). Potential for exposure most likely where exhaust emissions are confined by structures. |

|

Welding emissions |

Welders, tackers, fitters, operators of overhead cranes |

Work primarily involves carbon steel; aluminium and stainless steel are possible. Emissions include shield gases and fluxes, metal fumes, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, visible and ultraviolet energy. |

|

Brazing emissions |

Electricians working on traction motors |

Emission include cadmium end lead in solder. |

|

Thermal decomposition products from coatings |

Welders, tackers, fitters, grinders, operators of overhead cranes |

Emissions can include carbon monoxide, inorganic pigments containing lead and other chromates, decomposition products from paint resins. PCBs may have been used prior to 1971. PCBs can form furans and dioxins when heated. |

|

Cargo residues |

Welders, fitters, tackers, grinders, mechanics, strippers |

Residues reflect service in which car was used; cargoes could include heavy metal concentrates, coal, sulphur, lead ingots, etc. |

|

Abrasive blasting dust |

Abrasive blaster, bystanders |

Dust can contain cargo residues, blast material, paint dust. Paint applied prior to 1971 may contain PCBs. |

|

Solvent vapours |

Painter, bystanders |

Solvent vapours can be present in paint storage and mixing areas and paint booth; flammable mixtures may develop inside confined spaces, such as hoppers and tanks, during spraying. |

|

Paint aerosols |

Painter, bystanders |

Paint aerosols contain sprayed paint plus diluent; solvent in droplets and vapour can form flammable mixtures; resin system can include isocyanates, epoxys, amines, peroxides and other reactive intermediates. |

|

Confined spaces |

All shop workers |

Interior of some railcars, tanks and hoppers, nose of locomotive, ovens, degreasers, varnish impregnator, pits, sumps and other enclosed and partially enclosed structures |

|

Noise |

All shop workers |

Noise generated by many sources and tasks can exceed regulated limits. |

|

Hand-arm vibration |

Users of powered hand tools and hand-held equipment |

Vibration is transmitted through hand grips. |

|

Electromagnetic fields |

Users of electrical welding equipment |

AC and DC fields are possible, depending on design of the unit. |

|

Weather |

Outside workers |

Ultraviolet energy can cause sunburn, skin cancer and cataracts. Cold can cause cold stress and frostbite. Heat can cause heat stress. |

|

Shiftwork |

All workers |

Crews can work irregular hours. |

|

Musculoskeletal injury |

All workers |

Ankle injury can occur during disembarkment from moving equipment. Shoulder injury can occur during embarkment onto moving equipment or climbing onto cars. Work is performed in awkward posture especially when welding, burning, cutting and operating powered hand tools. |

|

Rundown accidents |

All workers |

Rundown can occur when the individual stands on active track and fails to hear approach of track equipment and moving cars. |

Maintenance of Track and Right of Way

Maintenance of track and right of way primarily involves work in the outdoor environment in conditions associated with the outdoors: sun, rain, snow, wind, cold air, hot air, blowing sand, biting and stinging insects, aggressive animals, snakes and poisonous plants.

Track and right-of-way maintenance can include track patrol, as well as the maintenance, rehabilitation and replacement of buildings and structures, track and bridges, or service functions, such as snowplowing and herbicide application, and may involve local operating units or large, specialized work gangs that deal with replacement of rails, ballast or ties. Equipment is available to almost completely mechanize each of these activities. Small-scale work, however, could involve small, powered equipment units or even be a completely manual activity.

In order to carry out maintenance of operating lines, a block of time must be available during which the work can occur. The block could become available at any time of day or night, depending on train scheduling, especially on a single-track main line. Thus, time pressure is a main consideration during this work, since the line must be returned to service at the end of the assigned block of time. Equipment must proceed to the site, the work must be completed, and the track vacated within the set period.

Ballast replacement and tie and rail replacement are complex tasks. Ballast replacement first involves removal of contaminated or deteriorated material in order to expose the track. A sled, a plow-like unit that is pulled by a locomotive, or an undercutter performs this task. The undercutter uses a continuous toothed chain to pull ballast to the side. Other equipment is used to remove and replace rail spikes or tie clips, tie plates (the metal plate on which the rail sits on the tie) and ties. Continuous rail is akin to a noodle of wet spaghetti that can flex and whip and that is easily moved vertically and laterally. Ballast is used to stabilize the rail. The ballast train delivers new ballast and pushes it into position. Labourers walk along with the train and systematically open chutes located at the bottom of the cars in order to enable ballast to flow.

After the ballast is dropped, a tamper uses hydraulic fingers to pack the ballast around and under the ties and lifts the track. A spud liner drives a metal spike into the roadbed as an anchor and moves the track into the desired position. The ballast regulator grades the ballast to establish the final contours of the roadbed and sweeps clean the surface of the ties and rails. Considerable dust is generated during ballast dumping, regulating and sweeping.

There are a variety of settings in which track work can take place—open areas, semi-enclosed areas such as cuts, and hill and cliff faces and confined spaces, such as tunnels and sheds. These have a profound influence on working conditions. Enclosed spaces, for example, will confine and concentrate exhaust emissions, ballast dust, dust from grinding, fumes from thermite welding, noise and other hazardous agents and conditions. (Thermite welding uses powdered aluminium and iron oxide. Upon ignition the aluminium burns intensely and converts the iron oxide to molten iron. The molten iron flows into the gap between the rails, welding them together end to end.)

Switching structures are associated with track. The switch contains moveable, tapered rails (points) and a wheel guide (frog). Both are manufactured from specially hardened steel containing a high level of manganese and chromium. The frog is an assembled structure containing several pieces of specially bent rail. The self-locking nuts which are used to bolt together these and other track structures may be cadmium-plated. Frogs are built up by welding and are ground during refurbishing, which can occur onsite or in shop facilities.

Bridge repainting is also an important part of right-of-way maintenance. Bridges often are situated in remote locations; this can considerably complicate provision of personal hygiene facilities which are needed to prevent contamination of individuals and the environment.

Table 3 summarizes the hazards of track and right-of-way maintenance.

Transportation Accidents

Possibly the greatest single concern in rail operations is the transportation accident. The large quantities of material that could be involved could cause serious problems of exposure of personnel and the environment. No amount of preparation for a worst-case accident is ever enough. Therefore, minimizing risk and the consequences of an accident are imperative. Transportation accidents occur for a variety of reasons: collisions at level crossings, obstruction of the track, failure of equipment and operator error.

The potential for such accidents can be minimized through conscientious and ongoing inspection and maintenance of track and right-of-way and equipment. The impact of a transportation accident involving a train carrying mixed cargo can be minimized through strategic positioning of cars that carry incompatible freight. Such strategic positioning, however, is not possible for a train hauling a single commodity. Commodities of particular concern include: pulverized coal, sulphur, liquefied petroleum (fuel) gases, heavy metal concentrates, solvents and process chemicals.

All of the groups in a rail organization are involved in transportation accidents. Rehabilitation activities can literally involve all groups working simultaneously at the same location on the site. Thus, coordination of these activities is extremely important, so that the actions of one group do not interfere with those of another.

Hazardous commodities generally remain contained during such accidents because of the attention given to crashproofing in the design of shipping containers and bulk rail cars. During an accident, the contents are removed from the damaged car by emergency response crews that represent the shipper. Equipment maintainers repair the damage to the extent possible and put the car back on the track, if possible. However, the track under the derailed car may have been destroyed. If so, repair or replacement of track occurs next, using prefabricated sections and techniques similar to those described above.

In some situations, loss of containment occurs and the contents of the car or shipping container spill onto the ground. If substances are shipped in quantities sufficient to require placarding because of transportation laws, they are readily identifiable on shipping manifests. However, highly hazardous substances that are shipped in smaller quantities than mandated for listing in a shipping manifest can escape identification and characterization for a considerable period. Containment at the site and collection of the spilled material are the responsibility of the shipper.

Railway personnel can be exposed to materials that remain in snow, soil or vegetation during rehabilitation efforts. The severity of exposure depends on the properties and quantity of the substance, the geometry of the site and weather conditions. The situation could also pose fire, explosion, reactivity and toxic hazards to humans, animals and the surrounding environment.

At some point following the accident, the site must be cleared so that the track can be put back into service. Transfer of cargo and repair of equipment and track may still be required. These activities could be dramatically complicated by the loss of containment and the presence of spilled material. Any action taken to address this type of situation requires considerable prior planning that includes input from specialized knowledgeable professionals.

Hazards and Precautions

Table 1, table 2 and table 3 summarize the hazardous conditions associated with the various groups of workers involved in railroad operations. Table 4 summarizes the types of precautions used to control these hazardous conditions.

Table 3. Hazardous conditions associated with maintenance on track and right of way.

|

Condition |

Affected group(s) |

Comments |

|

Exhaust emissions |

All workers |

Emissions include nitrogen dioxide, nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide and particulates containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Potential for exposure is most likely in unventilated tunnels and other circumstances where exhaust is confined by structures. |

|

Ballast dust/spilled cargo |

Track equipment operators, labourers |

Depending on the source, ballast dust can contain silica (quartz), heavy metals or asbestos. Track work around operations that produce and handle bulk commodities can cause exposure to these products: coal, sulphur, heavy metal concentrates, etc. |

|

Welding, cutting and grinding emissions |

Field and shop welders |

Welding primarily involves hardened steel; emissions can include shield gases and fluxes, metal fumes, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, ultraviolet and visible energy. Exposure to manganese and chromium can occur during work involving rail; cadmium may occur in plated nuts and bolts. |

|

Abrasive blasting dust |

Abrasive blaster, bystanders |

Dust contains blast material and paint dust; paint likely contains lead and other chromates. |

|

Solvent vapours |

Painter, bystanders |

Solvent vapours can be present in paint storage and mixing areas; flammable mixtures could develop inside enclosed spray structure during spraying. |

|

Paint aerosols |

Painter, bystanders |

Paint aerosols contain sprayed paint plus diluent; solvent in droplets and vapour can form flammable mixture; resin system can include isocyanates, epoxys, amines, peroxides and other reactive intermediates. |

|

Confined spaces |

All workers |

Interior of tunnels, culverts, tanks, hoppers, pits, sumps and other enclosed and partially enclosed structures |

|

Noise |

All workers |

Noise generated by many sources and tasks can exceed regulated limits. |

|

Whole-body vibration |

Truck drivers, track equipment operators |

Structure-borne vibration transmitted through the floor and seat in the cab originates from the engine and motion along roads and track and over gaps between rails. |

|

Hand-arm vibration |

Users of powered hand tools and hand-held equipment |

Vibration transmitted through hand grips |

|

Electromagnetic fields |

Users of electrical welding equipment |

AC and DC fields are possible, depending on design of the unit. |

|

Radio-frequency fields |

Users of two-way radios |

Effects on humans not fully established |

|

Weather-related |

Outside workers |

Ultraviolet energy can cause sunburn, skin cancer and cataracts; cold can cause cold stress and frostbite; heat can cause heat stress. |

|

Shiftwork |

All workers |

Gangs work irregular hours due to problems in scheduling blocks of track time. |

|

Musculoskeletal injury |

All workers |

Ankle injury during disembark from moving equipment; shoulder injury during embark onto moving equipment; work in awkward posture, especially when welding and operating powered hand tools |

|

Rundown accident |

All workers |

Rundown can occur when the individual stands on active track and fails to hear approach of track equipment, trains and moving cars. |

Table 4. Railway industry approached to controlling hazardous conditions.

|

Hazardous conditions |

Comments/control measures |

|

Exhaust emissions |

Locomotives have no exhaust stack. Exhaust discharges vertically from the top surface. Cooling fans also located on the top of the locomotive can direct exhaust-contaminated air into the airspace of tunnels and buildings. In-cab exposure during normal transit through a tunnel does not exceed exposure limits. Exposure during stationary operations in tunnels, such as investigation of mechanical problems, rerailing of derailed cars or track repair, can considerably exceed exposure limits. Stationary operation in shops also can create significant overexposure.Track maintenance and construction equipment and heavy vehicles usually have vertical exhaust stacks. Low-level discharge or discharge through horizontal deflectors can cause overexposure. Small vehicles and portable gasoline-powered equipment discharge exhaust downward or have no stack. Proximity to these sources can cause overexposure. Control measures include:

|

|

Noise |

Control measures include:

|

|

Whole-body vibration |

Control measures include:

|

|

Electromagnetic fields |

Hazard not established below present limits. |

|

Radio-frequency fields |

Hazard not established below present limits. |

|

Weather |

Control measures include:

|

|

Shiftwork |

Arrange work schedules to reflect current knowledge about circadian rhythms. |

|

Musculoskeletal injury |

Control measures include:

|

|

Video display units |

Apply office ergonomic principles to selection and utilization of video display units. |

|

Rundown accidents |

Rail equipment is confined to the track. Unpowered rail equipment creates little noise when in motion. Natural features can block noise from powered rail equipment. Equipment noise can mask warning sound from the horn of an approaching train. During operations in rail yards, switching can occur under remote control with the result that all tracks could be live. Control measures include:

|

|

Ballast operations/ spilled cargo |

Wetting ballast prior to track work eliminates dust from ballast and cargo residues. Personal and respiratory protective equipment should be provided. |

|

Skin contamination by waste oils and lubricants |

Equipment should be cleaned prior to dismantling to remove contamination. Protective clothing, gloves and/or barrier creams should be used. |

|

Welding, cutting and brazing emissions, grinding dust |

Control measures include:

|

|

Thermal decomposition products from coatings |

Control measures include:

|

|

Cargo residues |

Control measures include:

|

|

Abrasive blasting dust |

Control measures include:

|

|

Solvent vapours, paint aerosols |

Control measures include:

|

|

Confined spaces |

Control measures include:

|

|

Hand-arm vibration |

Control measures include:

|

Zoos and Aquariums

Zoological gardens, wildlife parks, safari parks, bird parks and collections of aquatic wildlife share similar methods for the maintenance and handling of exotic species. Animals are held for exhibition, as an educational resource, for conservation and for scientific study. Traditional methods of caging animals and preparing aviaries for birds and tanks for water creatures remain common, but more modern, progressive collections have adopted different enclosures designed to meet more of the needs of particular species. The quality of space accorded to an animal is more important than the quantity, however, which has consequential beneficial effects on keeper safety. The danger to keepers is often related to the size and natural ferocity of the species attended, but many other factors can affect the danger.

The main animal groupings are mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Problem areas that are common to all the animal groups are toxins, diseases that are contractible from animals (zoonoses) and changing animal moods.

Mammals

Mammals’ varied forms and habits require a wide range of husbandry techniques. The largest land forms are herbivorous, such as elephants, and are limited in their ability to climb, jump, burrow or gnaw, so their control is similar to domestic forms. Remote control of gates can offer high degrees of safety. Large predators such as big cats and bears require enclosures with wide margins of safety, double entry doors and in-built catch-ups and crushes. Agile climbing and jumping species pose special problems to keepers, who lack comparable mobility. The use of electric shock fence wiring is now widespread. Capture and handling methods include corralling, nets, crushing, roping, sedation and immobilization with drugs injected by dart.

Birds

Few birds are too large to be restrained by gloved hands and nets. The largest flightless birds—ostriches and cassowaries—are strong and have a very dangerous kick; they require crating for restraint.

Reptiles

Large carnivorous reptile species have violent strike attack capability; many snakes do too. Captive specimens may seem docile and induce keeper complacency. An attacking large constricting snake can overwhelm and suffocate a panicking keeper of much greater weight. A few venomous snakes can “spit”; thus eye protection against them should be mandatory. Restraint and handling methods include nets, bags, hooks, grabs, nooses and drugs.

Amphibians

Only a large giant salamander or big toad can give an unpleasant bite; otherwise risks from amphibians are from toxin excretion.

Fish

Few fish specimens are hazardous except for venomous species, electric eels and bigger predatory forms. Careful netting minimizes risk. Electric and chemical stunning may be occasionally appropriate.

Invertebrates

Some lethal invertebrate species are kept which require indirect handling. Mis-identification and specimens hidden by camouflage and small size can endanger the unwary.

Toxins

Many animal species have evolved complex poisons for feeding or defence, and deliver them by biting, stinging, spitting and secretion. Delivered quantities may vary from the inconsequential to lethal doses. Worst case scenarios should be the model for accident anticipation procedures. Single keeper exposure to lethal species should not be practised. Husbandry must include risk evaluation, unambiguous warning signs, restriction of handling to those trained, maintenance of stocks of antidotes (if any) in close liaison with local trained medical practitioners, predetermination of handler reaction to antidotes and an efficient alarm system.

Zoonoses

A good animal health programme and personal hygiene will keep the risk from zoonoses very low. However, there are many which are potentially lethal, such as rabies, which is untreatable in later stages. Almost all are avoidable, and treatable if diagnosed correctly early enough. As with work elsewhere, the incidence of allergy-related illness is rising and it is best treated by non-exposure to the irritant when identified.

“Non-venomous” bites and scratches require careful attention, as even a bite which appears not to break skin can lead to rapid blood poisoning (septicaemia). Carnivore and monkey bites should be especially suspect. An extreme example is the bite of a komodo dragon; the microflora in its saliva are so virulent that bitten large prey that escapes an initial attack will rapidly die from shock and septicaemia.

Routine prophylaxis against tetanus and hepatitis may be appropriate for many staff.

Moods

Animals can give an infinite variety of responses, some very dangerous, to close human presence. Observable mood changes can alert keepers to danger, but few animals show signs readable by humans. Moods can be influenced by a combination of seen and unseen stimuli such as season, day length, time of day, sexual rhythms, upbringing, hierarchy, barometric pressure and high-frequency noise from electrical equipment. Animals are not production line machines; they may have predictable patterns of behaviour but all have the capacity to do the unexpected, against which even the most skilled attendant must guard.

Personal safety

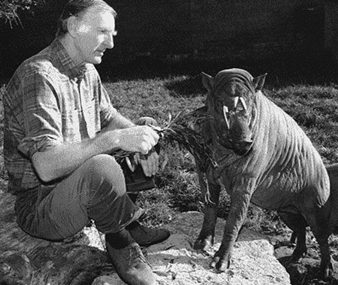

Risk appreciation should be taught by the skilled to the inexperienced. An undiminishing high level of caution will enhance personal safety, particularly, for example, when food is offered to larger carnivores. Animal responses will vary to different keepers, especially to those of different sex. An animal submissive to one person may attack another. The understanding and use of body language can enhance safety; animals naturally understand it better than humans. Voice tone and volume can calm or cause chaos (figure 1).

Figure 1. Handling animals with voice and body language.

Ken Sims

Clothing should be chosen with special care, avoiding bright, flapping material. Gloves may protect and reduce handling stress but are inappropriate for handling snakes because tactile sensitivity is reduced.

If keepers and other staff are expected to manage trespassing, violent or other problem visitors, they should be schooled in people management and have back-up on call to minimize risks to themselves.

Regulations

Despite the variety of potential risks from exotic species, the greater workplace hazards are conventional ones arising from plant and machinery, chemicals, surfaces, electricity and so on, so standard health and safety regulations must be applied with common sense and regard for the unusual nature of the work.

Prevention of Occupational Transmission of Bloodborne Pathogens

Prevention of occupational transmission of bloodborne pathogens (BBP) including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and more recently hepatitis C virus (HCV), has received significant attention. Although HCWs are the primary occupational group at risk of acquisition of infection, any worker who is exposed to blood or other potentially infectious body fluids during the performance of job duties is at risk. Populations at risk for occupational exposure to BBP include workers in health care delivery, public safety and emergency response workers and others such as laboratory researchers and morticians. The potential for occupational transmission of bloodborne pathogens including HIV will continue to increase as the number of persons who have HIV and other bloodborne infections and require medical care increases.

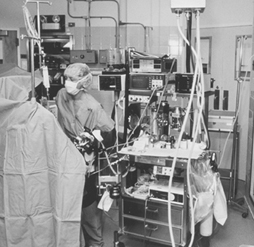

In the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended in 1982 and 1983 that patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) be treated according to the (now obsolete) category of “blood and body fluid precautions” (CDC 1982; CDC 1983). Documentation that HIV, the causative agent of AIDS, had been transmitted to HCWs by percutaneous and mucocutaneous exposures to HIV-infected blood, as well as the realization that the HIV infection status of most patients or blood specimens encountered by HCWs would be unknown at the time of the encounter, led CDC to recommend that blood and body fluid precautions be applied to all patients, a concept known as “universal precautions” (CDC 1987a, 1987b). The use of universal precautions eliminates the need to identify patients with bloodborne infections, but is not intended to replace general infection control practices. Universal precautions include the use of handwashing, protective barriers (e.g., goggles, gloves, gowns and face protection) when blood contact is anticipated and care in the use and disposal of needles and other sharp instruments in all health care settings. Also, instruments and other reusable equipment used in performing invasive procedures should be appropriately disinfected or sterilized (CDC 1988a, 1988b). Subsequent CDC recommendations have addressed prevention of transmission of HIV and HBV to public safety and emergency responders (CDC 1988b), management of occupational exposure to HIV, including the recommendations for the use of zidovudine (CDC 1990), immunization against HBV and management of HBV exposure (CDC 1991a), infection control in dentistry (CDC 1993) and the prevention of HIV transmission from HCWs to patients during invasive procedures (CDC 1991b).

In the US, CDC recommendations do not have the force of law, but have often served as the foundation for government regulations and voluntary actions by industry. The Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), a federal regulatory agency, promulgated a standard in 1991 on Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens (OSHA 1991). OSHA concluded that a combination of engineering and work practice controls, personal protective clothing and equipment, training, medical surveillance, signs and labels and other provisions can help to minimize or eliminate exposure to bloodborne pathogens. The standard also mandated that employers make available hepatitis B vaccination to their employees.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has also published guidelines and recommendations pertaining to AIDS and the workplace (WHO 1990, 1991). In 1990, the European Economic Council (EEC) issued a council directive (90/679/EEC) on protection of workers from risks related to exposure to biological agents at work. The directive requires employers to conduct an assessment of the risks to the health and safety of the worker. A distinction is drawn between activities where there is a deliberate intention to work with or use biological agents (e.g., laboratories) and activities where exposure is incidental (e.g., patient care). Control of risk is based on a hierarchical system of procedures. Special containment measures, according to the classification of the agents, are set out for certain types of health facilities and laboratories (McCloy 1994). In the US, CDC and the National Institutes of Health also have specific recommendations for laboratories (CDC 1993b).

Since the identification of HIV as a BBP, knowledge about HBV transmission has been helpful as a model for understanding modes of transmission of HIV. Both viruses are transmitted via sexual, perinatal and bloodborne routes. HBV is present in the blood of individuals positive for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg, a marker for high infectivity) at a concentration of approximately 108 to 109 viral particles per millilitre (ml) of blood (CDC 1988b). HIV is present in blood at much lower concentrations: 103 to 104 viral particles/ml for a person with AIDS and 10 to 100/ml for a person with asymptomatic HIV infection (Ho, Moudgil and Alam 1989). The risk of HBV transmission to a HCW after percutaneous exposure to HBeAg-positive blood is approximately 100-fold higher than the risk of HIV transmission after percutaneous exposure to HIV-infected blood (i.e., 30% versus 0.3%) (CDC 1989).

Hepatitis

Hepatitis, or inflammation of the liver, can be caused by a variety of agents, including toxins, drugs, autoimmune disease and infectious agents. Viruses are the most common cause of hepatitis (Benenson 1990). Three types of bloodborne viral hepatitis have been recognized: hepatitis B, formerly called serum hepatitis, the major risk to HCWs; hepatitis C, the major cause of parenterally transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis; and hepatitis D, or delta hepatitis.

Hepatitis B. The major infectious bloodborne occupational hazard to HCWs is HBV. Among US HCWs with frequent exposure to blood, the prevalence of serological evidence of HBV infection ranges between approximately 15 and 30%. In contrast, the prevalence in the general populations averages 5%. The cost-effectiveness of serological screening to detect susceptible individuals among HCWs depends on the prevalence of infection, the cost of testing and the vaccine costs. Vaccination of persons who already have antibodies to HBV has not been shown to cause adverse effects. Hepatitis B vaccine provides protection against hepatitis B for at least 12 years after vaccination; booster doses currently are not recommended. The CDC estimated that in 1991 there were approximately 5,100 occupationally acquired HBV infections in HCWs in the United States, causing 1,275 to 2,550 cases of clinical acute hepatitis, 250 hospitalizations and about 100 deaths (unpublished CDC data). In 1991, approximately 500 HCWs became HBV carriers. These individuals are at risk of long-term sequelae, including disabling chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and liver cancer.

The HBV vaccine is recommended for use in HCWs and public safety workers who may be exposed to blood in the workplace (CDC 1991b). Following a percutaneous exposure to blood, the decision to provide prophylaxis must include considerations of several factors: whether the source of the blood is available, the HBsAg status of the source and the hepatitis B vaccination and vaccine-response status of the exposed person. For any exposure of a person not previously vaccinated, hepatitis B vaccination is recommended. When indicated, hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) should be administered as soon as possible after exposure since its value beyond 7 days after exposure is unclear. Specific CDC recommendations are indicated in table 1 (CDC 1991b).

Table 1. Recommendation for post-exposure prophylaxis for percutaneous or permucosal exposure to hepatitis B virus, United States

|

Exposed person |

When source is |

||

|

HBsAg1 positive |

HBsAg negative |

Source not tested or |

|

|

Unvaccinated |

HBIG2´1 and initiate |

Initiate HB vaccine |

Initiate HB vaccine |

|

Previously Known |

No treatment |

No treatment |

No treatment |

|

Known non- |

HBIG´2 or HBIG´1 and |

No treatment |

If known high-risk source |

|

Response |

Test exposed for anti-HBs4 |

No treatment |

Test exposed for anti-HBs |

1 HBsAg = Hepatitis B surface antigen. 2 HBIG = Hepatitis B immune globulin; dose 0.06 mL/kg IM. 3 HB vaccine = hepatitis B vaccine. 4 Anti-HBs = antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen. 5 Adequate anti-HBs is ≥10 mIU/mL.

Table 2. Provisional US Public Health Service recommendations for chemoprophylaxis after occupational exposure to HIV, by type of exposure and source of material, 1996

|

Type of exposure |

Source material1 |

Antiretroviral |

Antiretroviral regimen3 |

|

Percutaneous |

Blood |

|

|

|

Mucous membrane |

Blood |

Offer |

ZDV plus 3TC, ± IDV5 |

|

Skin, increased risk7 |

Blood |

Offer |

ZDV plus 3TC, ± IDV5 |

1 Any exposure to concentrated HIV (e.g., in a research laboratory or production facility) is treated as percutaneous exposure to blood with highest risk. 2 Recommend—Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) should be recommended to the exposed worker with counselling. Offer—PEP should be offered to the exposed worker with counselling. Not offer—PEP should not be offered because these are not occupational exposures to HIV. 3 Regimens: zidovudine (ZDV), 200 mg three times a day; lamivudine (3TC), 150 mg two times a day; indinavir (IDV), 800 mg three times a day (if IDV is not available, saquinavir may be used, 600 mg three times a day). Prophylaxis is given for 4 weeks. For full prescribing information, see package inserts. 4 Risk definitions for percutaneous blood exposure: Highest risk—BOTH larger volume of blood (e.g., deep injury with large diameter hollow needle previously in source patient’s vein or artery, especially involving an injection of source-patient’s blood) AND blood containing a high titre of HIV (e.g., source with acute retroviral illness or end-stage AIDS; viral load measurement may be considered, but its use in relation to PEP has not been evaluated). Increased risk—EITHER exposure to larger volume of blood OR blood with a high titre of HIV. No increased risk—NEITHER exposure to larger volume of blood NOR blood with a high titre of HIV (e.g., solid suture needle injury from source patient with asymptomatic HIV infection). 5 Possible toxicity of additional drug may not be warranted. 6 Includes semen; vaginal secretions; cerebrospinal, synovial, pleural, peritoneal, pericardial and amniotic fluids. 7 For skin, risk is increased for exposures involving a high titre of HIV, prolonged contact, an extensive area, or an area in which skin integrity is visibly compromised. For skin exposures without increased risk, the risk for drug toxicity outweighs the benefit of PEP.

Article 14(3) of EEC Directive 89/391/EEC on vaccination required only that effective vaccines, where they exist, be made available for exposed workers who are not already immune. There was an amending Directive 93/88/EEC which contained a recommended code of practice requiring that workers at risk be offered vaccination free of charge, informed of the benefits and disadvantages of vaccination and non-vaccination, and be provided a certificate of vaccination (WHO 1990).

The use of hepatitis B vaccine and appropriate environmental controls will prevent almost all occupational HBV infections. Reducing blood exposure and minimizing puncture injuries in the health care setting will reduce also the risk of transmission of other bloodborne viruses.