Children categories

94. Education and Training Services (7)

94. Education and Training Services

Chapter Editor: Michael McCann

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Diseases affecting day-care workers & teachers

2. Hazards & precautions for particular classes

3. Summary of hazards in colleges & universities

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

95. Emergency and Security Services (9)

95. Emergency and Security Services

Chapter Editor: Tee L. Guidotti

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Recommendations & criteria for compensation

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

96. Entertainment and the Arts (31)

96. Entertainment and the Arts

Chapter Editor: Michael McCann

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Arts and Crafts

Performing and Media Arts

Entertainment

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Precautions associated with hazards

2. Hazards of art techniques

3. Hazards of common stones

4. Main risks associated with sculpture material

5. Description of fibre & textile crafts

6. Description of fibre & textile processes

7. Ingredients of ceramic bodies & glazes

8. Hazards & precautions of collection management

9. Hazards of collection objects

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see the figure in the article context.

97. Health Care Facilities and Services (25)

97. Health Care Facilities and Services

Chapter Editor: Annelee Yassi

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Health Care: Its Nature and Its Occupational Health Problems

Annalee Yassi and Leon J. Warshaw

Social Services

Susan Nobel

Home Care Workers: The New York City Experience

Lenora Colbert

Occupational Health and Safety Practice: The Russian Experience

Valery P. Kaptsov and Lyudmila P. Korotich

Ergonomics and Health Care

Hospital Ergonomics: A Review

Madeleine R. Estryn-Béhar

Strain in Health Care Work

Madeleine R. Estryn-Béhar

Case Study: Human Error and Critical Tasks: Approaches for Improved System Performance

Work Schedules and Night Work in Health Care

Madeleine R. Estryn-Béhar

The Physical Environment and Health Care

Exposure to Physical Agents

Robert M. Lewy

Ergonomics of the Physical Work Environment

Madeleine R. Estryn-Béhar

Prevention and Management of Back Pain in Nurses

Ulrich Stössel

Case Study: Treatment of Back Pain

Leon J. Warshaw

Health Care Workers and Infectious Disease

Overview of Infectious Diseases

Friedrich Hofmann

Prevention of Occupational Transmission of Bloodborne Pathogens

Linda S. Martin, Robert J. Mullan and David M. Bell

Tuberculosis Prevention, Control and Surveillance

Robert J. Mullan

Chemicals in the Health Care Environment

Overview of Chemical Hazards in Health Care

Jeanne Mager Stellman

Managing Chemical Hazards in Hospitals

Annalee Yassi

Waste Anaesthetic Gases

Xavier Guardino Solá

Health Care Workers and Latex Allergy

Leon J. Warshaw

The Hospital Environment

Buildings for Health Care Facilities

Cesare Catananti, Gianfranco Damiani and Giovanni Capelli

Hospitals: Environmental and Public Health Issues

M.P. Arias

Hospital Waste Management

M.P. Arias

Managing Hazardous Waste Disposal Under ISO 14000

Jerry Spiegel and John Reimer

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Examples of health care functions

2. 1995 integrated sound levels

3. Ergonomic noise reduction options

4. Total number of injuries (one hospital)

5. Distribution of nurses’ time

6. Number of separate nursing tasks

7. Distribution of nurses' time

8. Cognitive & affective strain & burn-out

9. Prevalence of work complaints by shift

10. Congenital abnormalities following rubella

11. Indications for vaccinations

12. Post-exposure prophylaxis

13. US Public Health Service recommendations

14. Chemicals’ categories used in health care

15. Chemicals cited HSDB

16. Properties of inhaled anaesthetics

17. Choice of materials: criteria & variables

18. Ventilation requirements

19. Infectious diseases & Group III wastes

20. HSC EMS documentation hierarchy

21. Role & responsibilities

22. Process inputs

23. List of activities

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see the figure in the article context.

98. Hotels and Restaurants (4)

98. Hotels and Restaurants

Chapter Editor: Pam Tau Lee

Table of Contents

99. Office and Retail Trades (7)

99. Office and Retail Trades

Chapter Editor: Jonathan Rosen

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

The Nature of Office and Clerical Work

Charles Levenstein, Beth Rosenberg and Ninica Howard

Professionals and Managers

Nona McQuay

Offices: A Hazard Summary

Wendy Hord

Bank Teller Safety: The Situation in Germany

Manfred Fischer

Telework

Jamie Tessler

The Retail Industry

Adrienne Markowitz

Case Study: Outdoor Markets

John G. Rodwan, Jr.

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Standard professional jobs

2. Standard clerical jobs

3. Indoor air pollutants in office buildings

4. Labour statistics in the retail industry

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

100. Personal and Community Services (6)

100. Personal and Community Services

Chapter Editor: Angela Babin

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Indoor Cleaning Services

Karen Messing

Barbering and Cosmetology

Laura Stock and James Cone

Laundries, Garment and Dry Cleaning

Gary S. Earnest, Lynda M. Ewers and Avima M. Ruder

Funeral Services

Mary O. Brophy and Jonathan T. Haney

Domestic Workers

Angela Babin

Case Study: Environmental Issues

Michael McCann

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Postures observed during dusting in a hospital

2. Dangerous chemicals used in cleaning

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

101. Public and Government Services (12)

101. Public and Government Services

Chapter Editor: David LeGrande

Table of Contents

Tables and Figurs

Occupational Health and Safety Hazards in Public and Governmental Services

David LeGrande

Case Report: Violence and Urban Park Rangers in Ireland

Daniel Murphy

Inspection Services

Jonathan Rosen

Postal Services

Roxanne Cabral

Telecommunications

David LeGrande

Hazards in Sewage (Waste) Treatment Plants

Mary O. Brophy

Domestic Waste Collection

Madeleine Bourdouxhe

Street Cleaning

J.C. Gunther, Jr.

Sewage Treatment

M. Agamennone

Municipal Recycling Industry

David E. Malter

Waste Disposal Operations

James W. Platner

The Generation and Transport of Hazardous Wastes: Social and Ethical Issues

Colin L. Soskolne

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Hazards of inspection services

2. Hazardous objects found in domestic waste

3. Accidents in domestic waste collection (Canada)

4. Injuries in the recycling industry

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

102. Transport Industry and Warehousing (18)

102. Transport Industry and Warehousing

Chapter Editor: LaMont Byrd

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

General Profile

LaMont Byrd

Case Study: Challenges to Workers’ Health and Safety in the Transportation and Warehousing Industry

Leon J. Warshaw

Air Transport

Airport and Flight Control Operations

Christine Proctor, Edward A. Olmsted and E. Evrard

Case Studies of Air Traffic Controllers in the United States and Italy

Paul A. Landsbergis

Aircraft Maintenance Operations

Buck Cameron

Aircraft Flight Operations

Nancy Garcia and H. Gartmann

Aerospace Medicine: Effects of Gravity, Acceleration and Microgravity in the Aerospace Environment

Relford Patterson and Russell B. Rayman

Helicopters

David L. Huntzinger

Road Transport

Truck and Bus Driving

Bruce A. Millies

Ergonomics of Bus Driving

Alfons Grösbrink and Andreas Mahr

Motor Vehicle Fuelling and Servicing Operations

Richard S. Kraus

Case Study: Violence in Gasoline Stations

Leon J. Warshaw

Rail Transport

Rail Operations

Neil McManus

Case Study: Subways

George J. McDonald

Water Transport

Water Transportation and the Maritime Industries

Timothy J. Ungs and Michael Adess

Storage

Storage and Transportation of Crude Oil, Natural Gas, Liquid Petroleum Products and Other Chemicals

Richard S. Kraus

Warehousing

John Lund

Case Study: US NIOSH Studies of Injuries among Grocery Order Selectors

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Bus driver seat measurements

2. Illumination levels for service stations

3. Hazardous conditions & administration

4. Hazardous conditions & maintenance

5. Hazardous conditions & right of way

6. Hazard control in the Railway industry

7. Merchant vessel types

8. Health hazards common across vessel types

9. Notable hazards for specific vessel types

10. Vessel hazard control & risk-reduction

11. Typical approximate combustion properties

12. Comparison of compressed & liquified gas

13. Hazards involving order selectors

14. Job safety analysis: Fork-lift operator

15. Job safety analysis: Order selector

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Overview of Chemical Hazards in Health Care

Exposure to potentially hazardous chemicals is a fact of life for health care workers. They are encountered in the course of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, in laboratory work, in preparation and clean-up activities and even in emanations from patients, to say nothing of the “infrastructure” activities common to all worksites such as cleaning and housekeeping, laundry, painting, plumbing and maintenance work. Despite the constant threat of such exposures and the large numbers of workers involved—in most countries, health care invariably is one of the most labour-intensive industries—this problem has received scant attention from those involved in occupational health and safety research and regulation. The great majority of chemicals in common use in hospitals and other health care settings are not specifically covered under national and international occupational exposure standards. In fact, very little effort has been made to date to identify the chemicals most frequently used, much less to study the mechanisms and intensity of exposures to them and the epidemiology of the effects on the health care workers involved.

This may be changing in the many jurisdictions in which right-to-know laws, such as the Canadian Workplace Hazardous Materials Information Systems (WHMIS) are being legislated and enforced. These laws require that workers be informed of the name and nature of the chemicals to which they may be exposed on the job. They have introduced a daunting challenge to administrators in the health care industry who must now turn to occupational health and safety professionals to undertake a de novo inventory of the identity and location of the thousands of chemicals to which their workers may be exposed.

The wide range of professions and jobs and the complexity of their interplay in the health care workplace require unique diligence and astuteness on the part of those charged with such occupational safety and health responsibilities. A significant complication is the traditional altruistic focus on the care and well-being of the patients, even at the expense of the health and well-being of those providing the services. Another complication is the fact that these services are often required at times of great urgency when important preventive and protective measures may be forgotten or deliberately disregarded.

Categories of Chemical Exposures in the Health Care Setting

Table 1 lists the categories of chemicals encountered in the health care workplace. Laboratory workers are exposed to the broad range of chemical reagents they employ, histology technicians to dyes and stains, pathologists to fixative and preservative solutions (formaldeyde is a potent sensitizer), and asbestos is a hazard to workers making repairs or renovations in older health care facilities.

Table 1. Categories of chemicals used in health care

|

Types of chemicals |

Locations most likely to be found |

|

Disinfectants |

Patient areas |

|

Sterilants |

Central supply |

|

Medicines |

Patient areas |

|

Laboratory reagents |

Laboratories |

|

Housekeeping/maintenance chemicals |

Hospital-wide |

|

Food ingredients and products |

Kitchen |

|

Pesticides |

Hospital-wide |

Even when liberally applied in combating and preventing the spread of infectious agents, detergents, disinfectants and sterilants offer relatively little danger to patients whose exposure is usually of brief duration. Even though individual doses at any one time may be relatively low, their cumulative effect over the course of a working lifetime may, however, constitute a significant risk to health care workers.

Occupational exposures to drugs can cause allergic reactions, such as have been reported over many years among workers administering penicillin and other antibiotics, or much more serious problems with such highly carcinogenic agents as the antineoplastic drugs. The contacts may occur during the preparation or administration of the dose for injection or in cleaning up after it has been administered. Although the danger of this mechanism of exposure had been known for many years, it was fully appreciated only after mutagenic activity was detected in the urine of nurses administering antineoplastic agents.

Another mechanism of exposure is the administration of drugs as aerosols for inhalation. The use of antineoplastic agents, pentamidine and ribavarin by this route has been studied in some detail, but there has been, as of this writing, no report of a systematic study of aerosols as a source of toxicity among health care workers.

Anaesthetic gases represent another class of drugs to which many health care workers are exposed. These chemicals are associated with a variety of biological effects, the most obvious of which are on the nervous system. Recently, there have been reports suggesting that repeated exposures to anaesthetic gases may, over time, have adverse reproductive effects among both male and female workers. It should be recognized that appreciable amounts of waste anaesthetic gases may accumulate in the air in recovery rooms as the gases retained in the blood and other tissues of patients are eliminated by exhalation.

Chemical disinfecting and sterilizing agents are another important category of potentially hazardous chemical exposures for health care workers. Used primarily in the sterilization of non-disposable equipment, such as surgical instruments and respiratory therapy apparatus, chemical sterilants such as ethylene oxide are effective because they interact with infectious agents and destroy them. Alkylation, whereby methyl or other alkyl groups bind chemically with protein-rich entities such as the amino groups in haemoglobiin and DNA, is a powerful biological effect. In intact organisms, this may not cause direct toxicity but should be considered potentially carcinogenic until proven otherwise. Ethylene oxide itself, however, is a known carcinogen and is associated with a variety of adverse health effects, as discussed elsewhere in the Encyclopaedia. The potent alkylation capability of ethylene oxide, probably the most widely-used sterilant for heat-sensitive materials, has led to its use as a classic probe in studying molecular structure.

For years, the methods used in the chemical sterilization of instruments and other surgical materials have carelessly and needlessly put many health care workers at risk. Not even rudimentary precautions were taken to prevent or limit exposures. For example, it was the common practice to leave the door of the sterilizer partially open to allow the escape of excess ethylene oxide, or to leave freshly-sterilized materials uncovered and open to the room air until enough had been assembled to make efficient use of the aerator unit.

The fixation of metallic or ceramic replacement parts so common in dentistry and orthopaedic surgery may be a source of potentially hazardous chemical exposure such as silica. These and the acrylic resins often used to glue them in place are usually biologically inert, but health care workers may be exposed to the monomers and other chemical reactants used during the preparation and application process. These chemicals are often sensitizing agents and have been associated with chronic effects in animals. The preparation of mercury amalgam fillings can lead to mercury exposure. Spills and the spread of mercury droplets is a particular concern since these may linger unnoticed in the work environment for many years. The acute exposure of patients to them appears to be entirely safe, but the long-term health implications of the repeated exposure of health care workers have not been adequately studied.

Finally, such medical techniques as laser surgery, electro-cauterization and use of other radiofrequency and high-energy devices can lead to the thermal degradation of tissues and other substances resulting in the formation of potentially toxic smoke and fumes. For example, the cutting of “plaster” casts made of polyester resin impregnated bandages has been shown to release potentially toxic fumes.

The hospital as a “mini-municipality”

A listing of the varied jobs and tasks performed by the personnel of hospitals and other large health care facilities might well serve as a table of contents for the commercial listings of a telephone directory for a sizeable municipality. All of these entail chemical exposures intrinsic to the particular work activity in addition to those that are peculiar to the health care environment. Thus, painters and maintenance workers are exposed to solvents and lubricants. Plumbers and others engaged in soldering are exposed to fumes of lead and flux. Housekeeping workers are exposed to soaps, detergents and other cleansing agents, pesticides and other household chemicals. Cooks may be exposed to potentially carcinogenic fumes in broiling or frying foods and to oxides of nitrogen from the use of natural gas as fuel. Even clerical workers may be exposed to the toners used in copiers and printers. The occurrence and effects of such chemical exposures are detailed elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia.

One chemical exposure that is diminishing in importance as more and more HCWs quit smoking and more health care facilities become “smoke-free” is “second hand” tobacco smoke.

Unusual chemical exposures in health care

Table 2 presents a partial listing of the chemicals most commonly encountered in health care workplaces. Whether or not they will be toxic will depend on the nature of the chemical and its biological proclivities, the manner, intensity and duration of the exposure, the susceptibilities of the exposed worker, and the speed and effectiveness of any countermeasures that may have been attempted. Unfortunately, a compendium of the nature, mechanisms, effects and treatment of chemical exposures of health care workers has not yet been published.

There are some unique exposures in the health care workplace that substantiate the dictum that a high level of vigilance is necessary to protect workers fully from such risks. For example, it was recently reported that health care workers had been overcome by toxic fumes emanating from a patient under treatment from a massive chemical exposure. Cases of cyanide poisoning arising from patient emissions have also been reported. In addition to the direct toxicity of waste anaesthetic gases to anaesthetists and other personnel in operating theatres, there is the often unrecognized problem created by the frequent use in such areas of high-energy sources which can transform the anaesthetic gases to free radicals, a form in which they are potentially carcinogenic.

Table 2. Chemicals cited Hazardous Substances Database (HSDB)

The following chemicals are listed in the HSDB as being used in some area of the health care environment. The HSDB is produced by the US National Library of Medicine and is a compilation of more than 4,200 chemicals with known toxic effects in commercial use. Absence of a chemical from the list does not imply that it is not toxic, but that it is not present in the HSDB.

|

Use list in the HSDB |

Chemical name |

CAS number* |

|

Disinfectants; antiseptics |

benzylalkonium chloride |

0001-54-5 |

|

Sterilants |

beta-propiolactone |

57-57-8 |

|

Laboratory reagents: |

2,4-xylidine (magenta-base) |

3248-93-9 |

* Chemical Abstracts identification number.

Water Transportation and the Maritime Industries

The very definition of the maritime setting is work and life that takes place in or around a watery world (e.g., ships and barges, docks and terminals). Work and life activities must first accommodate the macro-environmental conditions of the oceans, lakes or waterways in which they take place. Vessels serve as both workplace and home, so most habitat and work exposures are coexistent and inseparable.

The maritime industry comprises a number of sub-industries, including freight transportation, passenger and ferry service, commercial fishing, tankships and barge shipping. Individual maritime sub-industries consist of a set of merchant or commercial activities that are characterized by the type of vessel, targeted goods and services, typical practices and area of operations, and community of owners, operators and workers. In turn, these activities and the context in which they take place define the occupational and environmental hazards and exposures experienced by maritime workers.

Organized merchant maritime activities date back to the earliest days of civilized history. The ancient Greek, Egyptian and Japanese societies are examples of great civilizations where the development of power and influence was closely associated with having an extensive maritime presence. The importance of maritime industries to development of national power and prosperity has continued into the modern era.

The dominant maritime industry is water transportation, which remains the primary mode of international trade. The economies of most countries with ocean borders are heavily influenced by the receipt and export of goods and services by water. However, national and regional economies heavily dependent on the transport of goods by water are not limited to those which border oceans. Many countries removed from the sea have extensive networks of inland waterways.

Modern merchant vessels may process materials or produce goods as well as transport them. Globalized economies, restrictive land use, favourable tax laws and technology are among the factors which have spurred the growth of vessels that serve as both factory and means of transportation. Catcher-processor fishing vessels are a good example of this trend. These factory ships are capable of catching, processing, packaging and delivering finished sea food products to regional markets, as discussed in the chapter Fishing industry.

Merchant Transport Vessels

Similar to other transport vehicles, the structure, form and function of vessels closely parallel the vessel’s purpose and major environmental circumstances. For example, craft that transport liquids short distances on inland waterways will differ substantially in form and crew from those that carry dry bulk on trans-oceanic voyages. Vessels can be free moving, semi-mobile or permanently fixed structures (e.g., offshore oil-drilling rigs) and be self-propelled or towed. At any given time, existing fleets are comprised of a spectrum of vessels with a wide range of original construction dates, materials and degrees of sophistication.

Crew size will depend on the typical duration of trip, vessel purpose and technology, expected environmental conditions and sophistication of shore facilities. Larger crew size entails more extensive needs and elaborate planning for berthing, dining, sanitation, health care and personnel support. The international trend is toward vessels of increasing size and complexity, smaller crews and expanding reliance on automation, mechanization and containerization. Table 1 provides a categorization and descriptive summary of merchant vessel types.

Table 1. Merchant vessel types.

|

Vessel types |

Description |

Crew size |

|

Freight ships |

||

|

Bulk carrier

Break bulk

Container

Ore, bulk, oil (OBO)

Vehicle

Roll-on roll- off (RORO) |

Large vessel (200-600 feet (61-183 m)) typified by large open cargo holds and many voids; carry bulk cargoes such as grain and ore; cargo is loaded by chute, conveyor or shovel

Large vessel (200-600 feet (61-183 m)); cargo carried in bales, pallets, bags or boxes; expansive holds with between decks; may have tunnels

Large vessel (200-600 (61-183 m)) with open holds; may or may not have booms or cranes to handle cargo; containers are 20-40 feet (6.1-12.2 m) and stackable

Large vessel (200-600 feet (61-183 m)); holds are expansive and shaped to hold bulk ore or oil; holds are water tight, may have pumps and piping; many voids

Large vessel (200-600 feet (61-183 m)) with big sail area; many levels; vehicles can be self loading or boomed aboard

Large vessel (200-600 feet (61-183 m)) with big sail area; many levels; can carry other cargo in addition to vehicles |

25-50

25-60

25-45

25-55

25-40

25-40 |

|

Tank ships |

||

|

Oil

Chemical

Pressurized |

Large vessel (200-1000 feet (61-305 m)) typified by stern house piping on deck; may have hose handling booms and large ullages with many tanks; can carry crude or processed oil, solvents and other petroleum products

Large vessel (200-1000 feet (61-305 m)) similar to oil tankship, but may have additional piping and pumps to handle multiple cargoes simultaneously; cargoes can be liquid, gas, powders or compressed solids

Usually smaller (200-700 feet (61-213.4 m)) than typical tankship, having fewer tanks, and tanks which are pressurized or cooled; can be chemical or petroleum products such as liquid natural gas; tanks are usually covered and insulated; many voids, pipes and pumps |

25-50

25-50

15-30

|

|

Tug boats |

Small to mid-size vessel (80-200 feet (24.4-61 m)); harbour, push boats, ocean going |

3-15 |

|

Barge |

Mid-size vessel (100-350 feet (30.5-106.7 m)); can be tank, deck, freight or vehicle; usually not manned or self-propelled; many voids |

|

|

Drillships and rigs |

Large, similar profile to bulk carrier; typified by large derrick; many voids, machinery, hazardous cargo and large crew; some are towed, others self propelled |

40-120 |

|

Passenger |

All sizes (50-700 feet (15.2-213.4 m)); typified by large number of crew and passengers (up to 1000+) |

20-200 |

Morbidity and Mortality in the Maritime Industries

Health care providers and epidemiologists are often challenged to distinguish adverse health states due to work-related exposures from those due to exposures outside the workplace. This difficulty is compounded in the maritime industries because vessels serve as both workplace and home, and both exist in the greater environment of the maritime milieu itself. The physical boundaries found on most vessels result in close confinement and sharing of workspaces, engine-room, storage areas, passageways and other compartments with living spaces. Vessels often have a single water, ventilation or sanitation system that serves both work and living quarters.

The social structure aboard vessels is typically stratified into vessel officers or operators (ship’s master, first mate and so on) and remaining crew. Ship officers or operators are generally relatively more educated, affluent and occupationally stable. It is not uncommon to find vessels with crew members of an entirely different national or ethnic background from that of the officers or operators. Historically, maritime communities are more transient, heterogeneous and somewhat more independent than non-maritime communities. Work schedules aboard ship are often more fragmented and intermingled with non-work time than are land-based employment situations.

These are some reasons why it is difficult to describe or quantify health problems in the maritime industries, or to correctly associate problems with exposures. Data on maritime worker morbidity and mortality suffer from being incomplete and not representative of entire crews or sub-industries. Another shortfall of many data sets or information systems that report on the maritime industries is the inability to distinguish among health problems due to work, vessel or macro-environmental exposures. As with other occupations, difficulties in capturing morbidity and mortality information is most obvious with chronic disease conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease), particularly those with a long latency (e.g., cancer).

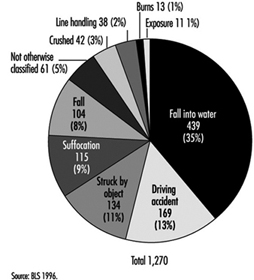

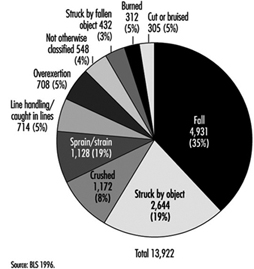

Review of 11 years (1983 to 1993) of US maritime data demonstrated that half of all fatalities due to maritime injuries, but only 12% of non-fatal injuries, are attributed to the vessel (i.e., collision or capsizing). The remaining fatalities and non-fatal injuries are attributed to personnel (e.g., mishaps to an individual while aboard ship). Reported causes of such mortality and morbidity are described in figure 1 and figure 2 respectively. Comparable information on non-injury-related mortality and morbidity is not available.

Figure 1. Causes of leading fatal unintentional injuries attributed to personal reasons (US maritime industries 1983-1993).

Figure 2. Causes of leading non-fatal unintentional injuries attributed to personal reasons (US maritime industries 1983-1993).

Combined vessel and personal US maritime casualty data reveal that the highest proportion (42%) of all maritime fatalities (N = 2,559), occurred among commercial fishing vessels. The next highest were among towboats/barges (11%), freight ships (10%) and passenger vessels (10%).

Analysis of reported work-related injuries for the maritime industries shows similarities to patterns reported for the manufacturing and construction industries. Commonalities are that most injuries are due to falls, being struck, cuts and bruises or muscular strains and overuse. Caution is needed when interpreting these data, however, as there is reporting bias: acute injuries are likely to be over-represented and chronic/latent injuries, which are less obviously connected to work, under-reported.

Occupational and Environmental Hazards

Most health hazards found in the maritime setting have land-based analogs in the manufacturing, construction and agricultural industries. The difference is that the maritime environment constricts and compresses available space, forcing close proximity of potential hazards and the intermingling of living quarters and workspaces with fuel tanks, engine and propulsion areas, cargo and storage spaces.

Table 2 summaries health hazards common across different vessel types. Health hazards of particular concern with specific vessel types are highlighted in table 3. The following paragraphs of this section expand discussion of selected environmental, physical and chemical, and sanitation health hazards.

Table 2. Health hazards common across vessel types.

|

Hazards |

Description |

Examples |

|

Mechanical |

Unguarded or exposed moving objects or their parts, which strike, pinch, crush or entangle. Objects can be mechanized (e.g., fork-lift) or simple (hinged door). |

Winches, pumps, fans, drive shafts, compressors, propellers, hatches, doors, booms, cranes, mooring lines, moving cargo |

|

Electrical |

Static (e.g., batteries) or active (e.g., generators) sources of electricity, their distribution system (e.g., wiring) and powered devices (e.g., motors), all of which can cause direct electrical-induced physical injury |

Batteries, vessel generators, dockside electrical sources, unprotected or ungrounded electric motors (pumps, fans, etc.), exposed wiring, navigation and communication electronics |

|

Thermal |

Heat- or cold-induced injury |

Steam pipes, cold storage spaces, power plant exhaust, cold- or warm-weather exposure above deck |

|

Noise |

Adverse auditory and other physiological problems due to excessive and prolonged sound energy |

Vessel propulsion system, pumps, ventilation fans, winches, steam-powered devices, conveyor belts |

|

Fall |

Slips, trips and falls resulting in kinetic-energy-induced injuries |

Steep ladders, deep vessel holds, missing railings, narrow gangways, elevated platforms |

|

Chemical |

Acute and chronic disease or injury resulting from exposure to organic or inorganic chemicals and heavy metals |

Cleaning solvents, cargo, detergents, welding, rusting/corrosion processes, refrigerants, pesticides, fumigants |

|

Sanitation |

Disease related to unsafe water, poor food practices or improper waste disposal |

Contaminated potable water, food spoilage, deteriorated vessel waste system |

|

Biologic |

Disease or illness causes by exposure to living organisms or their products |

Grain dust, raw wood products, cotton bales, bulk fruit or meat, seafood products, communicable disease agents |

|

Radiation |

Injury due to non-ionizing radiation |

Intense sunlight, arc welding, radar, microwave communications |

|

Violence |

Interpersonal violence |

Assault, homicide, violent conflict among crew |

|

Confined space |

Toxic or anoxic injury resulting from entering an enclosed space with limited entry |

Cargo holds, ballast tanks, crawl spaces, fuel tanks, boilers, storage rooms, refrigerated holds |

|

Physical work |

Health problems due to overuse, disuse or unsuitable work practices |

Shovelling ice in fish tanks, moving awkward cargo in restricted spaces, handling heavy mooring lines, prolonged stationary watch standing |

Table 3. Notable physical and chemical hazards for specific vessel types.

|

Vessel Types |

Hazards |

|

Tank vessels |

Benzene and various hydrocarbon vapours, hydrogen sulphide off-gassing from crude oil, inert gases used in tanks to create oxygen-deficient atmosphere for explosion control, fire and explosion due to combustion of hydrocarbon products |

|

Bulk cargo vessels |

Pocketing of fumigants used on agricultural products, personnel entrapment/suffocation in loose or shifting cargo, confined space risks in conveyor or man tunnels deep in vessel, oxygen deficiency due to oxidation or fermentation of cargo |

|

Chemical carriers |

Venting of toxic gases or dusts, pressurized air or gas release, leakage of hazardous substances from cargo holds or transfer pipes, fire and explosion due to combustion of chemical cargoes |

|

Container ships |

Exposure to spills or leakage due to failed or improperly stored hazardous substances; release of agricultural inerting gases; venting from chemical or gas containers; exposure to mislabeled substances that are hazardous; explosions, fire or toxic exposures due to mixing of separate substances to form a dangerous agent (e.g., acid and sodium cyanide) |

|

Break bulk vessels |

Unsafe conditions due to shifting of cargo or improper storage; fire, explosion or toxic exposures due to mixing of incompatible cargoes; oxygen deficiency due to oxidation or fermentation of cargoes; release of refrigerant gases |

|

Passenger ships |

Contaminated potable water, unsafe food preparation and storage practices, mass evacuation concerns, acute health problems of individual passengers |

|

Fishing vessels |

Thermal hazards from refrigerated holds, oxygen deficiency due to decomposition of seafood products or use of antioxidant preservatives, release of refrigerant gases, entanglement in netting or lines, contact with dangerous or toxic fish or sea animals |

Environmentalhazards

Arguably the most characteristic exposure defining the maritime industries is the pervasive presence of the water itself. The most variable and challenging of water environments is the open ocean. Oceans present constantly undulating surfaces, extremes of weather and hostile travel conditions, which combine to cause constant motion, turbulence and shifting surfaces and can result in vestibular disturbances (motion sickness), object instability (e.g., swinging latches and sliding gear) and the propensity to fall.

Humans have limited capability to survive unaided in open water; drowning and hypothermia are immediate threats upon immersion. Vessels serve as platforms that permit the human presence at sea. Ships and other water craft generally operate at some distance from other resources. For these reasons, vessels must dedicate a large proportion of total space to life support, fuel, structural integrity and propulsion, often at the expense of habitability, personnel safety and human factor considerations. Modern supertankers, which provide more generous human space and liveability, are an exception.

Excessive noise exposure is a prevalent problem because sound energy is readily transmitted through a vessel’s metallic structure to nearly all spaces, and limited noise attenuation materials are used. Excessive noise can be nearly continuous, with no available quiet areas. Sources of noise include the engine, propulsion system, machinery, fans, pumps and the pounding of waves on the vessel hull.

Mariners are an identified risk group for developing skin cancers, including malignant melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma. The increased risk is due to excess exposure to direct and water-surface-reflected ultraviolet solar radiation. Body areas of particular risk are exposed parts of the face, neck, ears and forearms.

Limited insulation, inadequate ventilation, internal sources of heat or cold (e.g., engine rooms or refrigerated spaces) and metallic surfaces all account for potential thermal stress. Thermal stress compounds physiological stress from other sources, resulting in reduced physical and cognitive performance. Thermal stress that is not adequately controlled or protected against can result in heat- or cold-induced injury.

Physical and chemical hazards

Table 3 highlights hazards unique or of particular concern to specific vessel types. Physical hazards are the most common and pervasive hazard aboard vessels of any type. Space limitations result in narrow passageways, limited clearance, steep ladders and low overheads. Confined vessel spaces means that machinery, piping, vents, conduits, tanks and so forth are squeezed in, with limited physical separation. Vessels commonly have openings that allow direct vertical access to all levels. Inner spaces below the surface deck are characterized by a combination of large holds, compact spaces and hidden compartments. Such physical structure places crew members at risk for slips, trips and falls, cuts and bruises, and being struck by moving or falling objects.

Constricted conditions result in being in close proximity to machinery, electrical lines, high-pressure tanks and hoses, and dangerously hot or cold surfaces. If unguarded or energized, contact can result in burns, abrasions, lacerations, eye damage, crushing or more serious injury.

Since vessels are basically a composite of spaces housed within a water-tight envelope, ventilation can be marginal or deficient in some spaces, creating a hazardous confined space situation. If oxygen levels are depleted or air is displaced, or if toxic gases enter these confined spaces, entry can be life threatening.

Refrigerants, fuels, solvents, cleaning agents, paints, inert gases and other chemical substances are likely to be found on any vessel. Normal ship activities, such as welding, painting and trash burning can have toxic effects. Transport vessels (e.g., freight ships, container ships and tank ships) can carry a host of biological or chemical products, many of which are toxic if inhaled, ingested or touched with the bare skin. Others can become toxic if allowed to degrade, become contaminated or mix with other agents.

Toxicity can be acute, as evidenced by dermal rashes and ocular burns, or chronic, as evidenced by neurobehavioural disorders and fertility problems or even carcinogenic. Some exposures can be immediately life-threatening. Examples of toxic chemicals carried by vessels are benzene-containing petrochemicals, acrylonitrile, butadiene, liquefied natural gas, carbon tetrachloride, chloroform, ethylene dibromide, ethylene oxide, formaldehyde solutions, nitropropane, o-toluidine and vinyl chloride.

Asbestos remains a hazard on some vessels, principally those constructed prior to the early 1970s. The thermal insulation, fire protection, durability and low cost of asbestos made this a preferred material in ship building. The primary hazard of asbestos occurs when the material becomes airborne when it is disturbed during renovations, construction or repair activities.

Sanitation and communicable disease hazards

One of the realities aboard ship is that the crew is often in close contact. In the work, recreation and living environments, crowding is often a fact of life that heightens the requirement for maintaining an effective sanitation programme. Critical areas include: berthing spaces, including toilet and shower facilities; food service and storage areas; laundry; recreation areas; and, if present, the barbershop. Pest and vermin control is also of critical importance; many of these animals can transmit disease. There are many opportunities for insects and rodents to infest a vessel, and once entrenched they are very difficult to control or eradicate, especially while underway. All vessels must have a safe and effective pest control programme. This requires training of individuals for this task, including annual refresher training.

Berthing areas must be kept free of debris, soiled laundry and perishable food. Bedding should be changed at least weekly (more often if soiled), and adequate laundry facilities for the size of the crew should be available. Food service areas must be rigorously maintained in a sanitary manner. The food service staff must receive training in proper techniques of food preparation, storage and galley sanitation, and adequate storage facilities must be provided aboard ship. The staff must adhere to recommended standards to ensure that food is prepared in a wholesome manner and is free of chemical and biological contamination. The occurrence of a food-borne disease outbreak aboard a vessel can be serious. A debilitated crew cannot carry out its duties. There may be insufficient medication to treat the crew, especially underway, and there may not be competent medical staff to care for the ill. In addition, if the ship is forced to change its destination, there may be significant economic loss to the shipping company.

The integrity and maintenance of a vessel’s potable water system is also of vital importance. Historically, water-borne outbreaks aboard ship have been the most common cause of acute disability and death among crews. Therefore, the potable water supply must come from an approved source (wherever possible) and be free from chemical and biological contamination. Where this is not possible, the vessel must have the means to effectively decontaminate the water and render it potable. A potable water system must be protected against contamination by every known source, including cross-contaminations with any non-potable liquids. The system also must be protected from chemical contamination. It must be cleaned and disinfected periodically. Filling the system with clean water containing at least 100 parts per million (ppm) of chlorine for several hours and then flushing the entire system with water containing 100 ppm chlorine is effective disinfection. The system should then be flushed with fresh potable water. A potable water supply must have at least 2 ppm residual of chlorine at all times, as documented by periodic testing.

Communicable disease transmission aboard ship is a serious potential problem. Lost work time, the cost of medical treatment and the possibility of having to evacuate crew members make this an important consideration. Besides the more common disease agents (e.g., those that cause gastroenteritis, such as Salmonella, and those that cause upper respiratory disease, such as the influenza virus), there has been a re-emergence of disease agents that were thought to be under control or eliminated from the general population. Tuberculosis, highly pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli and Streptococcus, and syphilis and gonorrhoea have reappeared in increasing incidence and/or virulence.

In addition, previously unknown or uncommon disease agents such as the HIV virus and the Ebola virus, which are not only highly resistant to treatment, but highly lethal, have appeared. It is therefore important that assessment be made of appropriate crew immunization for such diseases as polio, diphtheria, tetanus, measles, and hepatitis A and B. Additional immunizations may be required for specific potential or unique exposures, since crew members may have occasion to visit a wide variety of ports around the world and at the same time come in contact with a number of disease agents.

It is vital that crew members receive periodic training in the avoidance of contact with disease agents. The topic should include blood-borne pathogens, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), food- and water-borne diseases, personal hygiene, symptoms of the more common communicable diseases and appropriate action by the individual on discovering these symptoms. Communicable disease outbreaks aboard ship can have a devastating effect on the vessel’s operation; they can result in a high level of illness among the crew, with the possibility of serious debilitating disease and in some cases death. In some instances, vessel diversion has been required with resultant heavy economic losses. It is in the best interest of the vessel owner to have an effective and efficient communicable disease programme.

Hazard Control and Risk Reduction

Conceptually, the principles of hazard control and risk reduction are similar to other occupational settings, and include:

- hazard identification and characterization

- inventory and analysis of exposures and at-risk populations

- hazard elimination or control

- personnel monitoring and surveillance

- disease/injury prevention and intervention

- programme evaluation and adjustment (see table 4).

Table 4. Vessel hazard control & risk-reduction.

|

Topics |

Activities |

|

Programme development and evaluation |

Identify hazards, shipboard and dockside. |

|

Hazard identification |

Inventory shipboard chemical, physical, biological, and environmental hazards, in both work and living spaces (e.g., broken railings, use and storage of cleaning agents, presence of asbestos). |

|

Assessment of exposure |

Understand work practices and job tasks (prescribed as well as those actually done). |

|

Personnel at risk |

Review work logs, employment records and monitoring data of entire ship’s complement, both seasonal and permanent. |

|

Hazard control and |

Know established and recommended exposure standards (e.g., NIOSH, ILO, EU). |

|

Health surveillance |

Develop health information gathering and reporting system for all injuries and illnesses (e.g., maintain a ship’s daily binnacle). |

|

Monitor crew health |

Establish occupational medical monitoring, determine performance standards, and establish fitness-for-work criteria (e.g., pre-placement and periodic pulmonary testing of crew handling grain). |

|

Hazard control and risk reduction effectiveness |

Devise and set priorities for goals (e.g., reduce shipboard falls). |

|

Programme evolution |

Modify prevention and control activities based on changing circumstances and prioritization. |

To be effective, however, the means and methods to implement these principles must be tailored to the specific maritime arena of interest. Occupational activities are complex and take place in integrated systems (e.g., vessel operations, employee/employer associations, commerce and trade determinants). The key to prevention is to understand these systems and the context in which they take place, which requires close cooperation and interaction between all organizational levels of the maritime community, from general deck hand through vessel operators and company upper management. There are many government and regulatory interests that impact the maritime industries. Partnerships between government, regulators, management and workers are essential for meaningful programmes for improving the health and safety status of the maritime industries.

The ILO has established a number of Conventions and Recommendations relating to shipboard work, such as the Prevention of Accidents (Seafarers) Convention, 1970 (No. 134), and Recommendation, 1970 (No. 142), the Merchant Shipping (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1976 (No. 147), the Merchant Shipping (Improvement of Standards) Recommendation, 1976 (No. 155), and the Health Protection and Medical Care (Seafarers) Convention, 1987 (No. 164). The ILO has also published a Code of Practice regarding the prevention of accidents at sea (ILO 1996).

Approximately 80% of vessel casualties are attributed to human factors. Similarly, the majority of reported injury-related morbidity and mortality have human factor causes. Reduction in maritime injury and death requires successful application of principles of human factors to work and life activities aboard vessels. Successful application of human factors principles means that vessel operations, vessel engineering and design, work activities, systems and management policies are developed that integrate human anthropometrics, performance, cognition and behaviours. For example, cargo loading/unloading presents potential hazards. Human factor considerations would highlight the need for clear communication and visibility, ergonomic matching of worker to task, safe separation of workers from moving machinery and cargo and a trained workforce, well acquainted with work processes.

Prevention of chronic diseases and adverse health states with long latency periods is more problematic than injury prevention and control. Acute injury events generally have readily recognized cause-effect relationships. Also, the association of injury cause and effect with work practices and conditions is usually less complicated than for chronic diseases. Hazards, exposures and health data specific to the maritime industries are limited. In general, health surveillance systems, reporting and analyses for the maritime industries are less developed than those for many of their land-based counterparts. The limited availability of chronic or latent disease health data specific to maritime industries hinders development and application of targeted prevention and control programmes.

Are They Health Care Workers, Too?

Often overlooked when considering the safety and well-being of health care workers are students attending medical, dental, nursing and other schools for health professionals and volunteers serving pro bono in healthcare facilities. Since they are not “employees” in the technical or legal sense of the term, they are ineligible for workers’ compensation and employment-based health insurance in many jurisdictions. Health care administrators have only a moral obligation to be concerned about their health and safety.

The clinical segments of their training bring medical, nursing and dental students into direct contact with patients who may have infectious diseases. They perform or assist in a variety of invasive procedures, including taking blood samples, and often do laboratory work involving body fluids and specimens of urine and faeces. They are usually free to wander about the facility, entering areas containing potential hazards often, since such hazards are rarely posted, without an awareness of their presence. They are usually supervised very loosely, if at all, while their instructors are often not very knowledgeable, or even interested, in matters of safety and health protection.

Volunteers are rarely permitted to participate in clinical care but they do have social contacts with patients and they usually have few restrictions with respect to areas of the facility they may visit.

Under normal circumstances, students and volunteers share with health care workers the risks of exposure to potentially harmful hazards. These risks are exacerbated at times of crisis and in emergencies when they step into or are ordered into the breech. Clearly, even though it may not be spelled out in laws and regulations or in organizational procedure manuals, they are more than entitled to the concern and protection extended to “regular” health care workers.

Managing Chemical Hazards in Hospitals

The vast array of chemicals in hospitals, and the multitude of settings in which they occur, call for a systematic approach to their control. A chemical-by-chemical approach to prevention of exposures and their deleterious outcome is simply too inefficient to handle a problem of this scope. Moreover, as noted in the article “Overview of chemical hazards in health care”, many chemicals in the hospital environment have been inadequately studied; new chemicals are constantly being introduced and for others, even some that have become quite familiar (e.g., gloves made of latex), new hazardous effects are only now becoming manifest. Thus, while it is useful to follow chemical-specific control guidelines, a more comprehensive approach is needed whereby individual chemical control policies and practices are superimposed on a strong foundation of general chemical hazard control.

The control of chemical hazards in hospitals must be based on classic principles of good occupational health practice. Because health care facilities are accustomed to approaching health through the medical model, which focuses on the individual patient and treatment rather than on prevention, special effort is required to ensure that the orientation for handling chemicals is indeed preventive and that measures are principally focused on the workplace rather than on the worker.

Environmental (or engineering) control measures are the key to prevention of deleterious exposures. However, it is necessary to train each worker correctly in appropriate exposure prevention techniques. In fact, right-to-know legislation, as described below, requires that workers be informed of the hazards with which they work, as well as of the appropriate safety precautions. Secondary prevention at the level of the worker is the domain of medical services, which may include medical monitoring to ascertain whether health effects of exposure can be medically detected; it also consists of prompt and appropriate medical intervention in the event of accidental exposure. Chemicals that are less toxic must replace more toxic ones, processes should be enclosed wherever possible and good ventilation is essential.

While all means to prevent or minimize exposures should be implemented, if exposure does occur (e.g., a chemical is spilled), procedures must be in place to ensure prompt and appropriate response to prevent further exposure.

Applying the General Principles of Chemical Hazard Control in the Hospital Environment

The first step in hazard control is hazard identification. This, in turn, requires a knowledge of the physical properties, chemical constituents and toxicological properties of the chemicals in question. Material safety data sheets (MSDSs), which are becoming increasingly available by legal requirement in many countries, list such properties. The vigilant occupational health practitioner, however, should recognize that the MSDS may be incomplete, particularly with respect to long-term effects or effects of low-dose chronic exposure. Hence, a literature search may be contemplated to supplement the MSDS material, when appropriate.

The second step in controlling a hazard is characterizing the risk. Does the chemical pose a carcinogenic risk? Is it an allergen? A teratogen? Is it mainly short-term irritancy effects that are of concern? The answer to these questions will influence the way in which exposure is assessed.

The third step in chemical hazard control is to assess the actual exposure. Discussion with the health care workers who use the product in question is the most important element in this endeavour. Monitoring methods are necessary in some situations to ascertain that exposure controls are functioning properly. These may be area sampling, either grab sample or integrated, depending on the nature of the exposure; it may be personal sampling; in some cases, as discussed below, medical monitoring may be contemplated, but usually as a last resort and only as back-up to other means of exposure assessment.

Once the properties of the chemical product in question are known, and the nature and extent of exposure are assessed, a determination could be made as to the degree of risk. This generally requires that at least some dose-response information be available.

After evaluating the risk, the next series of steps is, of course, to control the exposure, so as to eliminate or at least minimize the risk. This, first and foremost, involves applying the general principles of exposure control.

Organizing a Chemical Control Programme in Hospitals

The traditional obstacles

The implementation of adequate occupational health programmes in health care facilities has lagged behind the recognition of the hazards. Labour relations are increasingly forcing hospital management to look at all aspects of their benefits and services to employees, as hospitals are no longer tacitly exempt by custom or privilege. Legislative changes are now compelling hospitals in many jurisdictions to implement control programmes.

However, obstacles remain. The preoccupation of the hospital with patient care, emphasizing treatment rather than prevention, and the staff’s ready access to informal “corridor consultation”, have hindered the rapid implementation of control programmes. The fact that laboratory chemists, pharmacists and a host of medical scientists with considerable toxicological expertise are heavily represented in management has, in general, not served to hasten the development of programmes. The question may be asked, “Why do we need an occupational hygienist when we have all these toxicology experts?” To the extent that changes in procedures threaten to have an impact on the tasks and services provided by these highly skilled personnel, the situation may be made worse: “We cannot eliminate the use of Substance X as it is the best bactericide around.” Or, “If we follow the procedure that you are recommending, patient care will suffer.” Moreover, the “we don’t need training” attitude is commonplace among the health care professions and hinders the implementation of the essential components of chemical hazard control. Internationally, the climate of cost constraint in health care is clearly also an obstacle.

Another problem of particular concern in hospitals is preserving the confidentiality of personal information about health care workers. While occupational health professionals should need only to indicate that Ms. X cannot work with chemical Z and needs to be transferred, curious clinicians are often more prone to push for the clinical explanation than their non-health care counterparts. Ms. X may have liver disease and the substance is a liver toxin; she may be allergic to the chemical; or she may be pregnant and the substance has potential teratogenic properties. While the need to alter the work assignment of particular individuals should not be routine, the confidentiality of the medical details should be protected if it is necessary.

Right-to-know legislation

Many jurisdictions around the world have implemented right-to-know legislation. In Canada, for example, WHMIS has revolutionized the handling of chemicals in industry. This country-wide system has three components: (1) the labelling of all hazardous substances with standardized labels indicating the nature of the hazard; (2) the provision of MSDSs with the constituents, hazards and control measures for each substance; and (3) the training of workers to understand the labels and the MSDSs and to use the product safely.

Under WHMIS in Canada and OSHA’s Hazard Communications requirements in the United States, hospitals have been required to construct inventories of all chemicals on the premises so that those that are “controlled substances” can be identified and addressed according to the legislation. In the process of complying with the training requirements of these regulations, hospitals have had to engage occupational health professionals with appropriate expertise and the spin-off benefits, particularly when bipartite train-the-trainer programmes were conducted, have included a new spirit to work cooperatively to address other health and safety concerns.

Corporate commitment and the role of joint health and safety committees

The most important element in the success of any occupational health and safety programme is corporate commitment to ensure its successful implementation. Policies and procedures regarding the safe handling of chemicals in hospitals must be written, discussed at all levels within the organization and adopted and enforced as corporate policy. Chemical hazard control in hospitals should be addressed by general as well as specific policies. For example, there should be a policy on responsibility for the implementation of right-to-know legislation that clearly outlines each party’s obligations and the procedures to be followed by individuals at each level of the organization (e.g., who chooses the trainers, how much work time is allowed for preparation and provision of training, to whom should communication regarding non-attendance be communicated and so on). There should be a generic spill clean-up policy indicating the responsibility of the worker and the department where the spill occurred, the indications and protocol for notifying the emergency response team, including the appropriate in-hospital and external authorities and experts, follow-up provisions for exposed workers and so on. Specific policies should also exist regarding the handling, storage and disposal of specific classes of toxic chemicals.

Not only is it essential that management be strongly committed to these programmes; the workforce, through its representatives, must also be actively involved in the development and implementation of policies and procedures. Some jurisdictions have legislatively mandated joint (labour-management) health and safety committees that meet at a minimum prescribed interval (bimonthly in the case of Manitoba hospitals), have written operating procedures and keep detailed minutes. Indeed in recognizing the importance of these committees, the Manitoba Workers’ Compensation Board (WCB) provides a rebate on WCB premiums paid by employers based on the successful functioning of these committees. To be effective, the members must be appropriately chosen—specifically, they must be elected by their peers, knowledgeable about the legislation, have appropriate education and training and be allotted sufficient time to conduct not only incident investigations but regular inspections. With respect to chemical control, the joint committee has both a pro-active and a re-active role: assisting in setting priorities and developing preventive policies, as well as serving as a sounding board for workers who are not satisfied that all appropriate controls are being implemented.

The multidisciplinary team

As noted above, the control of chemical hazards in hospitals requires a multidisciplinary endeavour. At a minimum, it requires occupational hygiene expertise. Generally hospitals have maintenance departments that have within them the engineering and physical plant expertise to assist a hygienist in determining whether workplace alterations are necessary. Occupational health nurses also play a prominent role in evaluating the nature of concerns and complaints, and in assisting an occupational physician in ascertaining whether clinical intervention is warranted. In hospitals, it is important to recognize that numerous health care professionals have expertise that is quite relevant to the control of chemical hazards. It would be unthinkable to develop policies and procedures for the control of laboratory chemicals without the involvement of lab chemists, for example, or procedures for handling anti-neoplastic drugs without the involvement of the oncology and pharmacology staff. While it is wise for occupational health professionals in all industries to consult with line staff prior to implementing control measures, it would be an unforgivable error to fail to do so in health care settings.

Data collection

As in all industries, and with all hazards, data need to be compiled both to help in priority setting and in evaluating the success of programmes. With respect to data collection on chemical hazards in hospitals, minimally, data need to be kept regarding accidental exposures and spills (so that these areas can receive special attention to prevent recurrences); the nature of concerns and complaints should be recorded (e.g., unusual odours); and clinical cases need to be tabulated, so that, for example, an increase in dermatitis from a given area or occupational group could be identified.

Cradle-to-grave approach

Increasingly, hospitals are becoming cognizant of their obligation to protect the environment. Not only the workplace hazardous properties, but the environmental properties of chemicals are being taken into consideration. Moreover, it is no longer acceptable to pour hazardous chemicals down the drain or release noxious fumes into the air. A chemical control programme in hospitals must, therefore, be capable of tracking chemicals from their purchase and acquisition (or, in some cases, synthesis on site), through the work handling, safe storage and finally to their ultimate disposal.

Conclusion

It is now recognized that there are thousands of potentially very toxic chemicals in the work environment of health care facilities; all occupational groups may be exposed; and the nature of the exposures are varied and complex. Nonetheless, with a systematic and comprehensive approach, with strong corporate commitment and a fully informed and involved workforce, chemical hazards can be managed and the risks associated with these chemicals controlled.

Social Services

Overview of the Social Work Profession

Social workers function in a wide variety of settings and work with many different kinds of people. They work in community health centres, hospitals, residential treatment centres, substance-abuse programmes, schools, family service agencies, adoption and foster care agencies, day-care facilities and public and private child welfare organizations. Social workers often visit homes for interviews or inspections of home conditions. They are employed by businesses, labour unions, international aid organizations, human rights agencies, prisons and probation departments, agencies for the ageing, advocacy organizations, colleges and universities. They are increasingly entering politics. Many social workers have full- or part-time private practices as psychotherapists. It is a profession that seeks to “improve social functioning by the provision of practical and psychological help to people in need” (Payne and Firth-Cozens 1987).

Generally, social workers with doctorates work in community organization, planning, research, teaching or combined areas. Those with bachelor’s degrees in social work tend to work in public assistance and with the elderly, mentally retarded and developmentally disabled; social workers with master’s degrees are usually found in mental health, occupational social work and medical clinics (Hopps and Collins 1995).

Hazards and Precautions

Stress

Studies have shown that stress in the workplace is caused, or contributed to, by job insecurity, poor pay, work overload and lack of autonomy. All of these factors are features of the work life of social workers in the late 1990s. It is now accepted that stress is often a contributing factor to illness. One study has shown that 50 to 70% of all medical complaints among social workers are linked to stress (Graham, Hawkins and Blau 1983).

As the social work profession has attained vendorship privileges, managerial responsibilities and increased numbers in private practice, it has become more vulnerable to professional liability and malpractice suits in countries such as the United States which permit such legal actions, a fact which contributes to stress. Social workers are also increasingly dealing with bioethical issues—those of life and death, of research protocols, of organ transplantation and of resource allocation. Often there is inadequate support for the psychological toll confronting these issues can take on involved social workers. Increased pressures of high caseloads as well as increased reliance on technology makes for less human contact, a fact which is likely true for most professions, but particularly difficult for social workers whose choice of work is so related to having face to face contact.

In many countries, there has been a shift away from government-funded social programmes. This policy trend directly affects the social work profession. The values and goals generally held by social workers—full employment, a “safety net” for the poor, equal opportunity for advancement—are not supported by these current trends.

The movement away from spending on programmes for the poor has produced what has been called an “upside-down welfare state” (Walz, Askerooth and Lynch 1983). One result of this, among others, has been increased stress for social workers. As resources decline, demand for services is on the rise; as the safety net frays, frustration and anger must rise, both for clients and for social workers themselves. Social workers may increasingly find themselves in conflict over respecting the values of the profession versus meeting statutory requirements. The code of ethics of the US National Association of Social Workers, for example, mandates confidentiality for clients which may be broken only when it is for “compelling professional reasons”. Further, social workers are to promote access to resources in the interest of “securing or retaining social justice”. The ambiguity of this could be quite problematic for the profession and a source of stress.

Violence

Work-related violence is a major concern for the profession. Social workers as problem-solvers on the most personal level are particularly vulnerable. They work with powerful emotions, and it is the relationship with their clients which becomes the focal point for expression of these emotions. Often, an underlying implication is that the client is unable to manage his or her own problems and needs the help of social workers to do so. The client may, in fact, be seeing social workers involuntarily, as, for example, in a child welfare setting where parental abilities are being evaluated. Cultural mores might also interfere with accepting offers of help from someone of another cultural background or sex (the preponderence of social workers are women) or outside of the immediate family. There may be language barriers, necessitating the use of translators. This can be distracting at least or even totally disruptive and may present a skewed picture of the situation at hand. These language barriers certainly affect the ease of communication, which is essential in this field. Further, social workers may work in locations which are in high-crime areas, or the work might take them into the “field” to visit clients who live in those areas.

Application of safety procedures is uneven in social agencies, and, in general, insufficient attention has been paid to this area. Prevention of violence in the workplace implies training, managerial procedures and modifications of the physical environment and/or communication systems (Breakwell 1989).

A curriculum for safety has been suggested (Griffin 1995) which would include:

- training in constructive use of authority

- crisis intervention

- field and office safety

- physical plant set-up

- general prevention techniques

- ways to predict potential violence.

Other Hazards

Because social workers are employed in such a variety of settings, they are exposed to many of the hazards of the workplace discussed elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia. Mention should be made, however, that these hazards include buildings with poor or unclean air flow (“sick buildings”) and exposures to infection. When funding is scarce, maintenance of physical plants suffers and risk of exposure increases. The high percentage of social workers in hospital and out-patient medical settings suggests vulnerability to infection exposure. Social workers see patients with conditions like hepatitis, tuberculosis and other highly contagious diseases as well as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. In response to this risk for all health workers, training and measures for infection control are necessary and have been mandated in many countries. The risk, however, persists.

It is evident that some of the problems faced by social workers are inherent in a profession which is so centred on lessening human suffering as well as one which is so affected by changing social and political climates. At the end of the twentieth century, the profession of social work finds itself in a state of flux. The values, ideals and rewards of the profession are also at the heart of the hazards it presents to its practitioners.

Waste Anaesthetic Gases

The use of inhaled anaesthetics was introduced in the decade of 1840 to 1850. The first compounds to be used were diethyl ether, nitrous oxide and chloroform. Cyclopropane and trichloroethylene were introduced many years later (circa 1930-1940), and the use of fluoroxene, halothane and methoxiflurane began in the decade of the 1950s. By the end of the 1960s enflurane was being used and, finally, isoflurane was introduced in the 1980s. Isoflurane is now considered the most widely used inhalation anaesthetic even though it is more expensive than the others. A summary of the physical and chemical characteristics of methoxiflurane, enflurane, halothane, isoflurane and nitrous oxide, the most commonly used anaesthetics, is shown in table 1 (Wade and Stevens 1981).

Table 1. Properties of inhaled anaesthetics

|

Isoflurane, |

Enflurane, |

Halothane, |

Methoxyflurane, |

Dinitrogen oxide, |

|

|

Molecular weight |

184.0 |

184.5 |

197.4 |

165.0 |

44.0 |

|

Boiling point |

48.5°C |

56.5°C |

50.2°C |

104.7°C |

— |

|

Density |

1.50 |

1.52 (25°C) |

1.86 (22°C) |

1.41 (25°C) |

— |

|

Vapour pressure at 20 °C |

250.0 |

175.0 (20°C) |

243.0 (20°C) |

25.0 (20°C) |

— |

|

Smell |

Pleasant, sharp |

Pleasant, like ether |

Pleasant, sweet |

Pleasant, fruity |

Pleasant, sweet |

|

Separation coefficients: |

|||||

|

Blood/gas |

1.40 |

1.9 |

2.3 |

13.0 |

0.47 |

|

Brain/gas |

3.65 |

2.6 |

4.1 |

22.1 |

0.50 |

|

Fat/gas |

94.50 |

105.0 |

185.0 |

890.0 |

1.22 |

|

Liver/gas |

3.50 |

3.8 |

7.2 |

24.8 |

0.38 |

|

Muscle/gas |

5.60 |

3.0 |

6.0 |

20.0 |

0.54 |

|

Oil/gas |

97.80 |

98.5 |

224.0 |

930.0 |

1.4 |

|

Water/gas |

0.61 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

4.5 |

0.47 |

|

Rubber/gas |

0.62 |

74.0 |

120.0 |

630.0 |

1.2 |

|

Metabolic rate |

0.20 |

2.4 |

15–20 |

50.0 |

— |

All of them, with the exception of nitrous oxide (N2O), are hydrocarbons or chlorofluorinated liquid ethers that are applied by vapourization. Isoflurane is the most volatile of these compounds; it is the one that is metabolized at the lowest rate and the one that is least soluble in blood, in fats and in the liver.