Children categories

64. Agriculture and Natural Resources Based Industries (34)

64. Agriculture and Natural Resources Based Industries

Chapter Editor: Melvin L. Myers

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

General Profile

Melvin L. Myers

Case Study: Family Farms

Ted Scharf, David E. Baker and Joyce Salg

Farming Systems

Plantations

Melvin L. Myers and I.T. Cabrera

Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers

Marc B. Schenker

Urban Agriculture

Melvin L. Myers

Greenhouse and Nursery Operations

Mark M. Methner and John A. Miles

Floriculture

Samuel H. Henao

Farmworker Education about Pesticides: A Case Study

Merri Weinger

Planting and Growing Operations

Yuri Kundiev and V.I. Chernyuk

Harvesting Operations

William E. Field

Storing and Transportation Operations

Thomas L. Bean

Manual Operations in Farming

Pranab Kumar Nag

Mechanization

Dennis Murphy

Case Study: Agricultural Machinery

L. W. Knapp, Jr.

Food and Fibre Crops

Rice

Malinee Wongphanich

Agricultural Grains and Oilseeds

Charles Schwab

Sugar Cane Cultivation and Processing

R.A. Munoz, E.A. Suchman, J.M. Baztarrica and Carol J. Lehtola

Potato Harvesting

Steven Johnson

Vegetables and Melons

B.H. Xu and Toshio Matsushita

Tree, Bramble and Vine Crops

Berries and Grapes

William E. Steinke

Orchard Crops

Melvin L. Myers

Tropical Tree and Palm Crops

Melvin L. Myers

Bark and Sap Production

Melvin L. Myers

Bamboo and Cane

Melvin L. Myers and Y.C. Ko

Specialty Crops

Tobacco Cultivation

Gerald F. Peedin

Ginseng, Mint and Other Herbs

Larry J. Chapman

Mushrooms

L.J.L.D. Van Griensven

Aquatic Plants

Melvin L. Myers and J.W.G. Lund

Beverage Crops

Coffee Cultivation

Jorge da Rocha Gomes and Bernardo Bedrikow

Tea Cultivation

L.V.R. Fernando

Hops

Thomas Karsky and William B. Symons

Health and Environmental Issues

Health Problems and Disease Patterns in Agriculture

Melvin L. Myers

Case Study: Agromedicine

Stanley H. Schuman and Jere A. Brittain

Environmental and Public Health Issues in Agriculture

Melvin L. Myers

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Sources of nutrients

2. Ten steps for a plantation work risk survey

3. Farming systems in urban areas

4. Safety advice for lawn & garden equipment

5. Categorization of farm activities

6. Common tractor hazards & how they occur

7. Common machinery hazards & where they occur

8. Safety precautions

9. Tropical & subtropical trees, fruits & palms

10. Palm products

11. Bark & sap products & uses

12. Respiratory hazards

13. Dermatological hazards

14. Toxic & neoplastic hazards

15. Injury hazards

16. Lost time injuries, United States, 1993

17. Mechanical & thermal stress hazards

18. Behavioural hazards

19. Comparison of two agromedicine programmes

20. Genetically engineered crops

21. Illicit drug cultivation, 1987, 1991 & 1995

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see the figure in the article context.

65. Beverage Industry (10)

65. Beverage Industry

Chapter Editor: Lance A. Ward

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

General Profile

David Franson

Soft Drink Concentrate Manufacturing

Zaida Colon

Soft Drink Bottling and Canning

Matthew Hirsheimer

Coffee Industry

Jorge da Rocha Gomes and Bernardo Bedrikow

Tea Industry

Lou Piombino

Distilled Spirits Industry

R.G. Aldi and Rita Seguin

Wine Industry

Alvaro Durao

Brewing Industry

J.F. Eustace

Health and Environmental Concerns

Lance A. Ward

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Selected coffee importers (in tonnes)

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

66. Fishing (10)

66. Fishing

Chapter Editors: Hulda Ólafsdóttir and Vilhjálmur Rafnsson

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

General Profile

Ragnar Arnason

Case Study: Indigenous Divers

David Gold

Major Sectors and Processes

Hjálmar R. Bárdarson

Psychosocial Characteristics of the Workforce at Sea

Eva Munk-Madsen

Psychosocial Characteristics of the Workforce in On-Shore Fish Processing

Marit Husmo

Social Effects of One-Industry Fishery Villages

Barbara Neis

Health Problems and Disease Patterns

Vilhjálmur Rafnsson

Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Fishermen and Workers in the Fish Processing Industry

Hulda Ólafsdóttir

Commercial Fisheries: Environmental and Public Health Issues

Bruce McKay and Kieran Mulvaney

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Mortality figures on fatal injuries among fishermen

2. The most important jobs or places related to risk of injuries

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

67. Food Industry (11)

67. Food Industry

Chapter Editor: Deborah E. Berkowitz

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Overview and Health Effects

Food Industry Processes

M. Malagié, G. Jensen, J.C. Graham and Donald L. Smith

Health Effects and Disease Patterns

John J. Svagr

Environmental Protection and Public Health Issues

Jerry Spiegel

Food Processing Sectors

Meatpacking/Processing

Deborah E. Berkowitz and Michael J. Fagel

Poultry Processing

Tony Ashdown

Dairy Products Industry

Marianne Smukowski and Norman Brusk

Cocoa Production and the Chocolate Industry

Anaide Vilasboas de Andrade

Grain, Grain Milling and Grain-Based Consumer Products

Thomas E. Hawkinson, James J. Collins and Gary W. Olmstead

Bakeries

R.F. Villard

Sugar-Beet Industry

Carol J. Lehtola

Oil and Fat

N.M. Pant

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. The food industries, their raw materials & processes

2. Common occupational diseases in the food & drink industries

3. Types of infections reported in food & drink industries

4. Examples of uses for by-products from the food industry

5. Typical water reuse ratios for different industry sub-sectors

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

68. Forestry (17)

68. Forestry

Chapter Editor: Peter Poschen

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

General Profile

Peter Poschen

Wood Harvesting

Dennis Dykstra and Peter Poschen

Timber Transport

Olli Eeronheimo

Harvesting of Non-wood Forest Products

Rudolf Heinrich

Tree Planting

Denis Giguère

Forest Fire Management and Control

Mike Jurvélius

Physical Safety Hazards

Bengt Pontén

Physical Load

Bengt Pontén

Psychosocial Factors

Peter Poschen and Marja-Liisa Juntunen

Chemical Hazards

Juhani Kangas

Biological Hazards among Forestry Workers

Jörg Augusta

Rules, Legislation, Regulations and Codes of Forest Practices

Othmar Wettmann

Personal Protective Equipment

Eero Korhonen

Working Conditions and Safety in Forestry Work

Lucie Laflamme and Esther Cloutier

Skills and Training

Peter Poschen

Living Conditions

Elías Apud

Environmental Health Issues

Shane McMahon

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Forest area by region (1990)

2. Non-wood forest product categories & examples

3. Non-wood harvesting hazards & examples

4. Typical load carried while planting

5. Grouping of tree-planting accidents by body parts affected

6. Energy expenditure in forestry work

7. Chemicals used in forestry in Europe & North America in the 1980s

8. Selection of infections common in forestry

9. Personal protective equipment appropriate for forestry operations

10. Potential benefits to environmental health

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

69. Hunting (2)

69. Hunting

Chapter Editor: George A. Conway

Table of Contents

Tables

A Profile of Hunting and Trapping in the 1990s

John N. Trent

Diseases Associated with Hunting and Trapping

Mary E. Brown

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Examples of diseases potentially significant to hunters & trappers

70. Livestock Rearing (21)

70. Livestock Rearing

Chapter Editor: Melvin L. Myers

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Livestock Rearing: Its Extent and Health Effects

Melvin L. Myers

Health Problems and Disease Patterns

Kendall Thu, Craig Zwerling and Kelley Donham

Case Study: Arthopod-related Occupational Health Problems

Donald Barnard

Forage Crops

Lorann Stallones

Livestock Confinement

Kelley Donham

Animal Husbandry

Dean T. Stueland and Paul D. Gunderson

Case Study: Animal Behaviour

David L. Hard

Manure and Waste Handling

William Popendorf

A Checklist for Livestock Rearing Safety Practice

Melvin L. Myers

Dairy

John May

Cattle, Sheep and Goats

Melvin L. Myers

Pigs

Melvin L. Myers

Poultry and Egg Production

Steven W. Lenhart

Case Study: Poultry Catching, Live Hauling and Processing

Tony Ashdown

Horses and Other Equines

Lynn Barroby

Case Study: Elephants

Melvin L. Myers

Draught Animals in Asia

D.D. Joshi

Bull Raising

David L. Hard

Pet, Furbearer and Laboratory Animal Production

Christian E. Newcomer

Fish Farming and Aquaculture

George A. Conway and Ray RaLonde

Beekeeping, Insect Raising and Silk Production

Melvin L. Myers and Donald Barnard

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Livestock uses

2. International livestock production (1,000 tonnes)

3. Annual US livestock faeces & urine production

4. Types of human health problems associated with livestock

5. Primary zoonoses by world region

6. Different occupations & health & safety

7. Potential arthropod hazards in the workplace

8. Normal & allergic reactions to insect sting

9. Compounds identified in swine confinement

10. Ambient levels of various gases in swine confinement

11. Respiratory diseases associated with swine production

12. Zoonotic diseases of livestock handlers

13. Physical properties of manure

14. Some important toxicologic benchmarks for hydrogen sulphide

15. Some safety procedures related to manure spreaders

16. Types of ruminants domesticated as livestock

17. Livestock rearing processes & potential hazards

18. Respiratory illnesses from exposures on livestock farms

19. Zoonoses associated with horses

20. Normal draught power of various animals

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see the figure in article context.

71. Lumber (4)

71. Lumber

Chapter Editors: Paul Demers and Kay Teschke

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

General Profile

Paul Demers

Major Sectors and Processes: Occupational Hazards and Controls

Hugh Davies, Paul Demers, Timo Kauppinen and Kay Teschke

Disease and Injury Patterns

Paul Demers

Environmental and Public Health Issues

Kay Teschke and Anya Keefe

Tables

Click a link below to view the table in the article context.

1. Estimated wood production in 1990

2. Estimated production of lumber for the 10 largest world producers

3. OHS hazards by lumber industry process area

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see the figure in article context.

72. Paper and Pulp Industry (13)

72. Paper and Pulp Industry

Chapter Editors: Kay Teschke and Paul Demers

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

General Profile

Kay Teschke

Major Sectors and Processes

Fibre Sources for Pulp and Paper

Anya Keefe and Kay Teschke

Wood Handling

Anya Keefe and Kay Teschke

Pulping

Anya Keefe, George Astrakianakis and Judith Anderson

Bleaching

George Astrakianakis and Judith Anderson

Recycled Paper Operations

Dick Heederik

Sheet Production and Converting: Market Pulp, Paper, Paperboard

George Astrakianakis and Judith Anderson

Power Generation and Water Treatment

George Astrakianakis and Judith Anderson

Chemical and By-product Production

George Astrakianakis and Judith Anderson

Occupational Hazards and Controls

Kay Teschke, George Astrakianakis, Judith Anderson, Anya Keefe and Dick Heederik

Disease and Injury Patterns

Injuries and Non-malignant Diseases

Susan Kennedy and Kjell Torén

Cancer

Kjell Torén and Kay Teschke

Environmental and Public Health Issues

Anya Keefe and Kay Teschke

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Employment & production in selected countries (1994)

2. Chemical constituents of pulp & paper fibre sources

3. Bleaching agents & their conditions of use

4. Papermaking additives

5. Potential health & safety hazards by process area

6. Studies on lung & stomach cancer, lymphoma & leukaemia

7. Suspensions & biological oxygen demand in pulping

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Mushrooms

The world’s most widely cultivated edible fungi are: the common white button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus, with an annual production in 1991 of approximately 1.6 million tonnes; the oyster mushroom, Pleurotus spp. (about 1 million tonnes); and the shiitake, Lentinus edodes (about 0.6 million tonnes) (Chang 1993). Agaricus is mainly grown in the western hemisphere, whereas oyster mushrooms, shiitake and a number of other fungi of lesser production are mostly produced in East Asia.

The production of Agaricus and the preparation of its substrate, compost, are for a large part strongly mechanized. This is generally not the case for the other edible fungi, although exceptions exist.

The Common Mushroom

The common white button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus, is grown on compost consisting of a fermented mixture of horse manure, wheat straw, poultry manure and gypsum. The materials are wetted, mixed and set in large heaps when fermented outdoors, or brought into special fermentation rooms, called tunnels. Compost is usually made in quantities of up to several hundred tonnes per batch, and large, heavy equipment is used for mixing heaps and for filling and emptying the tunnels. Composting is a biological process that is guided by a temperature regime and that requires thorough mixing of the ingredients. Before being used as a substrate for growth, compost should be pasteurized by heat treatment and conditioned to get rid of the ammonia. During composting, a considerable amount of sulphur-containing organic volatiles evaporates, which can cause odour problems in the surroundings. When tunnels are used, the ammonia in the air can be cleaned by acid washing, and odour escape can be prevented by either biological or chemical oxidation of the air (Gerrits and Van Griensven 1990).

The ammonia-free compost is then spawned (i.e., inoculated with a pure culture of Agaricus growing on sterilized grain). Mycelial growth is carried out during a 2-week incubation at 25 °C in a special room or in a tunnel, after which the grown compost is placed in growing rooms in trays or in shelves (i.e., a scaffold system with 4 to 6 beds or tiers above each other with a distance of 25 to 40 cm in between), covered with a special casing consisting of peat and calcium carbonate. After a further incubation, mushroom production is induced by a temperature change combined with strong ventilation. Mushrooms appear in flushes with weekly intervals. They are either harvested mechanically or hand-picked. After 3 to 6 flushes, the growing room is cooked out (i.e., steam pasteurized), emptied, cleaned and disinfected, and the next growing cycle can be started.

Success in mushroom cultivation depends heavily on cleanliness and prevention of pests and diseases. Although management and farm hygiene are key factors in disease prevention, a number of disinfectants and a limited number of pesticides and fungicides are still used in the industry.

Health Risks

Electrical and mechanical equipment

A pre-eminent risk in mushroom farms is the accidental exposure to electricity. Often high voltage and amperage is used in humid environments. Ground fault circuit interrupters and other electrical precautions are necessary. National labour legislation usually sets rules for the protection of labourers; this should be strictly followed.

Also, mechanical equipment may pose dangerous threats by its damaging weight or function, or by the combination of both. Composting machines with their large moving parts require care and attention to prevent accidents. Equipment used in cultivation and harvesting often has rotating parts used as grabbers or harvesting knives; their use and transport require great care. Again, this holds for all machines that are moving, whether they be self-propelled or pulled over beds, shelves or rows of trays. All such equipment should be properly guarded. All personnel whose duties include handling electrical or mechanical equipment in mushroom farms should be carefully trained before work is started and safety rules should be adhered to. Maintenance ordinances of equipment and machines should be taken very seriously. A proper lockout/tagout programme is needed as well. Lack of maintenance causes mechanical equipment to become extremely dangerous. For example, breaking pull chains have caused several deaths in mushroom farms.

Physical factors

Physical factors such as climate, lighting, noise, muscle load and posture strongly influence the health of workers. The difference between ambient outside temperature and that of a growing room can be considerable, especially in the winter. One should allow the body to adapt to a new temperature with every change of location; not doing so may lead to diseases of the airways and eventually to a susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections. Further, exposure to excessive temperature changes may cause muscles and joints to become stiff and inflamed. This may lead to a stiff neck and back, a painful condition causing unfitness for work.

Insufficient lighting in mushroom-growing rooms not only causes dangerous working conditions but also slows down picking, and it prevents pickers from seeing the possible symptoms of disease in the crop. The lighting intensity should be at least 500 lux.

Muscle load and posture largely determine the weight of labour. Unnatural body positions are often required in manual cultivation and picking tasks due to the limited space in many growing rooms. Those positions may damage joints and cause static overload of the muscles; prolonged static loading of muscles, such as that which occurs during picking, can even cause inflammation of joints and muscles, eventually leading to partial or total loss of function. This can be prevented by regular breaks, physical exercises and ergonomic measures (i.e., adaptation of the actions to the dimensions and possibilities of the human body).

Chemical factors

Chemical factors such as exposure to hazardous substances create possible health risks. The large-scale preparation of compost has a number of processes that can pose lethal risks. Gully pits in which recirculation water and drainage from compost is collected are usually devoid of oxygen, and the water contains high concentrations of hydrogen sulphide and ammonia. A change in acidity (pH) of the water may cause a lethal concentration of hydrogen sulphide to occur in the areas surrounding the pit. Piling wet poultry or horse manure in a closed hall may cause the hall to become an essentially lethal environment, due to the high concentrations of carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulphide and ammonia which are generated. Hydrogen sulphide has a powerful odour at low concentrations and is especially threatening, since at lethal concentrations this compound appears to be odourless because it inactivates human olfactory nerves. Indoor compost tunnels do not have sufficient oxygen to support human life. They are confined spaces, and testing of air for oxygen content and toxic gases, wearing of appropriate PPE, having an outside guard and proper training of involved personnel are essential.

Acid washers used for removal of ammonia from the air of compost tunnels require special care because of the large quantities of strong sulphuric or phosphoric acid that are present. Local exhaust ventilation should be provided.

Exposure to disinfectants, fungicides and pesticides can take place through the skin by exposure, through the lungs by breathing, and through the mouth by swallowing. Usually fungicides are applied by a high-volume technique such as by spray lorries, spray guns and drenching. Pesticides are applied with low-volume techniques such as misters, dynafogs, turbofogs and by fumigation. The small particles that are created remain in the air for hours. The right protective clothing and a respirator that has been certified as appropriate for the chemicals involved should be worn. Although the effects of acute poisoning are very dramatic, it should not be forgotten that the effects of chronic poisoning, although less dramatic at first glance, also always require occupational health surveillance.

Biological factors

Biological agents can cause infectious diseases as well as severe allergic reactions (Pepys 1967). No human infectious disease cases caused by the presence of human pathogens in compost have been reported. However, mushroom worker’s lung (MWL) is a severe respiratory disease that is associated with handling the compost for Agaricus (Bringhurst, Byrne and Gershon-Cohen 1959). MWL, which belongs to the group of diseases designated extrinsic allergic alveolitis (EAA), arise from exposure to spores of the thermophilic actinomycetes Excellospora flexuosa, Thermomonospora alba, T. curvata and T. fusca that have grown during the conditioning phase in compost. They can be present in high concentrations in the air during spawning of phase 2 compost (i.e., over 109 colony-forming units (CFU) per cubic metre of air) (Van den Bogart et al. 1993); for causation of EAA symptoms, 108 spores per cubic metre of air are sufficient (Rylander 1986). The symptoms of EAA and thus MWL are fever, difficult respiration, cough, malaise, increase in number of leukocytes and restrictive changes of lung function, starting only 3 to 6 hours after exposure (Sakula 1967; Stolz, Arger and Benson 1976). After a prolonged period of exposure, irreparable damage is done to the lung due to inflammation and reactive fibrosis. In one study in the Netherlands, 19 MWL patients were identified among a group of 1,122 workers (Van den Bogart 1990). Each patient demonstrated a positive response to inhalation provocation and possessed circulating antibodies against spore antigens of one or more of the actinomycetes mentioned above. No allergic reaction had been found with Agaricus spores (Stewart 1974), which may indicate low antigenicity of the mushroom itself or low exposure. MWL can easily be prevented by providing workers with powered air-purifying respirators equipped with a fine dust filter as part of their normal work gear during spawning of compost.

Some pickers have been found to suffer from damaged skin of finger tips, caused by exogenous glucanases and proteases of Agaricus. Wearing gloves during picking prevents this.

Stress

Mushroom growing has a short and complicated growing cycle. Thus managing a mushroom farm brings worries and tensions which may extend to the workforce. Stress and its management are discussed elsewhere in this Encyclopaedia.

The Oyster Mushroom

Oyster mushrooms, Pleurotus spp., can be grown on a number of different lignocellulose-containing substrates, even on cellulose itself. The substrate is wetted and usually pasteurized and conditioned. After spawning, mycelial growth takes place in trays, shelves, special containers or in plastic bags. Fructification takes place when the ambient carbon dioxide concentration is decreased by ventilation or by opening the container or bag.

Health risks

Health risks associated with the cultivation of oyster mushrooms are comparable to those linked to Agaricus as described above, with one major exception. All Pleurotus species have naked lamellae (i.e., not covered by a veil), which results in the early shedding of a large number of spores. Sonnenberg, Van Loon and Van Griensven (1996) have counted spore production in Pleurotus spp. and found up to a billion spores produced per gram of tissue per day, depending on species and developmental stage. The so-called sporeless varieties of Pleurotus ostreatus produced about 100 million spores. Many reports have described the occurrence of EAA symptoms after exposure to Pleurotus spores (Hausen, Schulz and Noster 1974; Horner et al. 1988; Olson 1987). Cox, Folgering and Van Griensven (1988) have established the causal relation between exposure to Pleurotus spores and occurrence of EAA symptoms caused by inhalation. Because of the serious nature of the disease and the high sensitivity of humans, all workers should be protected with dust respirators. Spores in the growing room should at least partially be removed before workers enter the room. This can be done by directing the circulation air over a wet filter or by setting ventilation at full power 10 minutes before workers enter the room. Weighing and packing of mushrooms can be done under a hood, and during storage the trays should be covered by foil to prevent release of spores into the working environment.

Shiitake Mushrooms

In Asia this tasty mushroom, Lentinus edodes, has been grown on wood logs in the open air for centuries. The development of a low-cost cultivation technique on artificial substrate in growing rooms rendered its culture economically feasible in the western world. The artificial substrates usually consist of a wetted mixture of hardwood sawdust, wheat straw and high-concentration protein meal, which is pasteurized or sterilized before spawning. Mycelial growth takes place in bags, or in trays or shelves, depending on the system used. Fruiting is commonly induced by temperature shock or by immersion in ice-cold water, as is done to induce production on wood logs. Due to its high acidity (low pH), the substrate is susceptible to infection by green moulds such as Penicillium spp. and Trichoderma spp. Prevention of the growth of those heavy sporulators requires either sterilization of the substrate or use of fungicides.

Health risks

The health risks associated with the cultivation of shiitake are comparable with those of Agaricus and Pleurotus. Many strains of shiitake sporulate easily, leading to concentrations of up to 40 million spores per cubic metre of air (Sastre et al. 1990).

Indoor cultivation of shiitake has regularly led to EAA symptoms in workers (Cox, Folgering and Van Griensven 1988, 1989; Nakazawa, Kanatani and Umegae 1981; Sastre et al. 1990) and inhalation of spores of shiitake is the cause of the disease (Cox, Folgering and Van Griensven 1989). Van Loon et al. (1992) have shown that in a group of 5 patients tested, all had circulating IgG-type antibodies against shiitake spore antigens. Despite the use of protective mouth masks, a group of 14 workers experienced a rise in antibody titres with increased duration of employment, indicating the need for better prevention, such as powered air-purifying respirators and appropriate engineering controls.

Acknowledgement: The view and results presented here are strongly influenced by the late Jef Van Haaren, M.D., a fine person and gifted occupational health physician, whose humane approach to the effects of human labour was best reflected in Van Haaren (1988), his chapter in my textbook that formed the basis of the present article.

Aquatic Plants

Adapted from J.W.G. Lund’s article, “Algae”, “Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety,” 3rd edition.

Worldwide aquaculture production totalled 19.3 million tonnes in 1992, of which 5.4 million tonnes came from plants. In addition, much of the feed used on fish farms is water plants and algae, contributing to their growth as a part of aquaculture.

Water plants that are grown commercially include water spinach, watercress, water chestnuts, lotus stems and various seaweeds, which are grown as low-cost foods in Asia and Africa. Floating water plants that have commercial potential are duckweed and water hyacinth (FAO 1995).

Algae are a diverse group of organisms; if the cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) are included, they come in a range of sizes from bacteria (0.2 to 2 microns) to giant kelps (40 m). All algae are capable of photosynthesis and can liberate oxygen.

Algae are nearly all aquatic, but they may also live as a dual organism with fungi as lichens on drier rocks and on trees. Algae are found wherever there is moisture. Plant plankton consists almost exclusively of algae. Algae abound in lakes and rivers, and on the seashore. The slipperiness of stones and rocks, the slimes and discolourations of water usually are formed by aggregations of microscopic algae. They are found in hot springs, snowfields and Antarctic ice. On mountains they can form dark slippery streaks (Tintenstriche) that are dangerous to climbers.

There is no general agreement about algae classification, but they are commonly divided into 13 major groups whose members may differ markedly from one group to another in colour. The blue-green algae (Cyanophyta) are also considered by many microbiologists to be bacteria (Cyanobacteria) because they are procaryotes, which lack the membrane-bounded nuclei and other organelles of eukaryotic organisms. They are probably descendants of the earliest photosynthetic organisms, and their fossils have been found in rocks some 2 billion years old. Green algae (Chlorophyta), to which Chlorella belongs, has many of the characteristics of other green plants. Some are seaweeds, as are most of the red (Rhodophyta) and brown (Phaeophyta) algae. Chrysophyta, usually yellow or brownish in colour, include the diatoms, algae with walls made of polymerized silicon dioxide. Their fossil remains form industrially valuable deposits (Kieselguhr, diatomite, diatomaceous earth). Diatoms are the main basis of life in the oceans and contribute about 20 to 25% of the world’s plant production. Dinoflagellates (Dinophyta) are free-swimming algae especially common in the sea; some are toxic.

Uses

Water culture can vary greatly from the traditional 2-month to annual growing cycle of planting, then fertilizing and plant maintenance, followed by harvesting, processing, storage and sale. Sometimes the cycle is compressed to 1 day, such as in duckweed farming. Duckweed is the smallest flowering plant.

Some seaweeds are valuable commercially as sources of alginates, carrageenin and agar, which are used in industry and medicine (textiles, food additives, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, emulsifiers and so on). Agar is the standard solid medium on which bacteria and other micro-organisms are cultivated. In the Far East, especially in Japan, a variety of seaweeds are used as human food. Seaweeds are good fertilizers, but their use is decreasing because of the labour costs and the availability of relatively cheap artificial fertilizers. Algae play an important part in tropical fish farms and in rice fields. The latter are commonly rich in Cyanophyta, some species of which can utilize nitrogen gas as their sole source of nitrogenous nutrient. As rice is the staple diet of the majority of the human race, the growth of algae in rice fields is under intensive study in countries such as India and Japan. Certain algae have been employed as a source of iodine and bromine.

The use of industrially cultivated microscopic algae has often been advocated for human food and has a potential for very high yields per unit area. However, the cost of dewatering has been a barrier.

Where there is a good climate and inexpensive land, algae can be used as part of the process of sewage purification and harvested as animal food. While a useful part of the living world of reservoirs, too much algae can seriously impede, or increase the cost of water supply. In swimming pools, algal poisons (algicides) can be used to control algal growth, but, apart from copper in low concentrations, such substances cannot be added to water or domestic supplies. Over-enrichment of water with nutrients, notably phosphorus, with consequent excessive growth of algae, is a major problem in some regions and has led to bans on the use of phosphorus-rich detergents. The best solution is to remove the excess phosphorus chemically in a sewage plant.

Duckweed and a water hyacinth are potential livestock feeds, compost input or fuel. Aquatic plants are also used as feed for noncarnivorous fish. Fish farms produce three primary commodities: finfish, shrimp and mollusc. Of the finfish portion, 85% are made up of noncarnivorous species, primarily the carp. Both the shrimp and mollusc depend upon algae (FAO 1995).

Hazards

Abundant growths of freshwater algae often contain potentially toxic blue-green algae. Such “water blooms” are unlikely to harm humans because the water is so unpleasant to drink that swallowing a large and hence dangerous amount of algae is unlikely. On the other hand, cattle may be killed, especially in hot, dry areas where no other source of water may be available to them. Paralytic shellfish poisoning is caused by algae (dinoflagellates) on which the shellfish feed and whose powerful toxin they concentrate in their bodies with no apparent harm to themselves. Humans, as well as marine animals, can be harmed or killed by the toxin.

Prymnesium (Chrysophyta) is very toxic to fish and flourishes in weakly or moderately saline water. It presented a major threat to fish farming in Israel until research provided a practical method of detecting the presence of the toxin before it reached lethal proportions. A colourless member of the green algae (Prototheca) infects humans and other mammals from time to time.

There have been a few reports of algae causing skin irritations. Oscillatoria nigroviridis are known to cause dermatitis. In freshwater, Anaebaena, Lyngbya majuscula and Schizothrix can cause contact dermatitis. Red algae are known to cause breathing distress. Diatoms contain silica, so they could pose a silicosis hazard as a dust. Drowning is a hazard when working in deeper water while cultivating and harvesting water plants and algae. The use of algicides also poses hazards, and precautions provided on the pesticide label should be followed.

Tea Cultivation

Adapted from 3rd edition, “Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety”.

Tea (Camellia sinensis) was originally cultivated in China, and most of the world’s tea still comes from Asia, with lesser quantities from Africa and South America. Ceylon and India are now the largest producers, but sizeable quantities also come from China, Japan, the former USSR, Indonesia and Pakistan. The Islamic Republic of Iran, Turkey, Viet Nam and Malaysia are small-scale growers. Since the Second World War, the area under tea cultivation in Africa has been expanding rapidly, particularly in Kenya, Mozambique, Congo, Malawi, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania. Mauritius, Rwanda, Cameroon, Zambia and Zimbabwe also have small acreages. The main South American producers are Argentina, Brazil and Peru.

Plantations

Tea is most efficiently and economically produced in large plantations, although it is also grown as a smallholder crop. In Southeast Asia, the tea plantation is a self-contained unit, providing accommodation and all facilities for its workers and their families, each unit forming a virtually closed community. Women form a large proportion of the workers in India and Ceylon, but the pattern is somewhat different in Africa, where mainly male migrant and seasonal labour is employed and families do not have to be housed. See also the article “Plantations” [AGR03AE] in this chapter.

Cultivation

Land is cleared and prepared for new planting, or areas of old, poor-quality tea are uprooted and replanted with high-yielding vegetatively propagated cuttings. New fields take a couple of years to come into full bearing. Regular programmes of manuring, weeding and pesticide application are carried on throughout the year.

The plucking of the young tea leaves—the famous “two leaves and a bud”—takes place the year round in most of Southeast Asia, but is restricted in areas with a marked cold season (see figure 1). After a cycle of plucking which lasts about 3 to 4 years, bushes are pruned back fairly drastically and the area weeded. Hand weeding is now widely giving way to the use of chemical herbicides. The plucked tea is collected in baskets carried on the backs of the pluckers and taken down to centrally located weighing sheds, and from these to the factories for processing. In some countries, notably Japan and the former USSR, mechanical plucking has been carried out with some success, but this requires a reasonably flat terrain and bushes grown in set rows.

Figure 1. Tea pluckers at work on a plantation in Uganda

Hazards and Their Prevention

Falls and injuries caused by agricultural implements of the cutting and digging type are the most common types of accidents. This is not unexpected, considering the steep slopes on which tea is generally grown and the type of work involved in the processes of clearing, uprooting and pruning. Apart from exposure to natural hazards like lightning, workers are liable to be bitten by snakes or stung by hornets, spiders, wasps or bees, although highly venomous snakes are seldom found at the high altitudes at which the best tea grows. An allergic condition caused by contact with a certain species of caterpillar has been recorded in Assam, India.

The exposure of workers to ever-increasing quantities of highly toxic pesticides requires careful control. Substitution with less-toxic pesticides and attention to personal hygiene are necessary measures here. Mechanization has been fairly slow, but an increasing number of tractors, powered vehicles and implements are coming into use, with a concomitant increase in accidents from these causes (see figure 2). Well-designed tractors with safety cabs, operated by trained, competent drivers will eliminate many accidents.

Figure 2. Mechanical harvesting on a tea plantation near the Black Sea

In Asia, where the non-working population resident on the tea estates is almost as great as the workforce itself, the total number of accidents in the home is equal to that of accidents in the field.

Housing is generally substandard. The most common diseases are those of the respiratory system, closely followed by enteric diseases, anaemia and substandard nutrition. The former are mainly the outcome of working and living conditions at high altitudes and exposure to low temperatures and inclement weather. The intestinal diseases are due to poor sanitation and low standards of hygiene among the labour force. These are mainly preventable conditions, which underlines the need for better sanitary facilities and improved health education. Anaemia, particularly among working mothers of child-bearing age, is all too common; it is partly the result of ankylostomiasis, but is due mainly to protein-deficient diets. However, the principal causes of lost work time are generally from the more minor ailments and not serious diseases. Medical supervision of both housing and working conditions is an essential preventive measure, and official inspection, either at local or national level, is also necessary to ensure that proper health facilities are maintained.

General Profile

Forestry—A Definition

For the purposes of the present chapter, forestry is understood to embrace all the fieldwork required to establish, regenerate, manage and protect forests and to harvest their products. The last step in the production chain covered by this chapter is the transport of raw forest products. Further processing, such as into sawnwood, furniture or paper is dealt with in the Lumber, Woodworking and Pulp and paper industries chapters in this Encyclopaedia.

The forests may be natural, human-made or tree plantations. Forest products considered in this chapter are both wood and other products, but emphasis is on the former, because of its relevance for safety and health.

Evolution of the Forest Resource and the Sector

The utilization and management of forests are as old as the human being. Initially forests were almost exclusively used for subsistence: food, fuelwood and building materials. Early management consisted mostly of burning and clearing to make room for other land uses—in particular, agriculture, but later also for settlements and infrastructure. The pressure on forests was aggravated by early industrialization. The combined effect of conversion and over-utilization was a sharp reduction in forest area in Europe, the Middle East, India, China and later in parts of North America. Presently, forests cover about one-quarter of the land surface of the earth.

The deforestation process has come to a halt in industrialized countries, and forest areas are actually increasing in these countries, albeit slowly. In most tropical and subtropical countries, however, forests are shrinking at a rate of 15 to 20 million hectares (ha), or 0.8%, per year. In spite of continuing deforestation, developing countries still account for about 60% of the world forest area, as can be seen in table 1. The countries with the largest forest areas by far are the Russian Federation, Brazil, Canada and the United States. Asia has the lowest forest cover in terms of percentage of land area under forest and hectares per capita.

Table 1. Forest area by region (1990).

|

Region |

Area (million hectares) |

% total |

|

Africa |

536 |

16 |

|

North/Central America |

531 |

16 |

|

South America |

898 |

26 |

|

Asia |

463 |

13 |

|

Oceania |

88 |

3 |

|

Europe |

140 |

4 |

|

Former USSR |

755 |

22 |

|

Industrialized (all) |

1,432 |

42 |

|

Developing (all) |

2,009 |

58 |

|

World |

3,442 |

100 |

Source: FAO 1995b.

Forest resources vary significantly in different parts of the world. These differences have a direct impact on the working environment, on the technology used in forestry operations and on the level of risk associated with them. Boreal forests in northern parts of Europe, Russia and Canada are mostly made up of conifers and have a relatively small number of trees per hectare. Most of these forests are natural. Moreover, the individual trees are small in size. Because of the long winters, trees grow slowly and wood increment ranges from less than 0.5 to 3 m3/ha/y.

The temperate forests of southern Canada, the United States, Central Europe, southern Russia, China and Japan are made up of a wide range of coniferous and broad-leaved tree species. Tree densities are high and individual trees can be very large, with diameters of more than 1 m and tree height of more than 50 m. Forests may be natural or human-made (i.e., intensively managed with more uniform tree sizes and fewer tree species). Standing volumes per hectare and increment are high. The latter range typically from 5 to greater than 20 m3/ha/y.

Tropical and subtropical forests are mostly broad-leaved. Tree sizes and standing volumes vary greatly, but tropical timber harvested for industrial purposes is typically in the form of large trees with big crowns. Average dimensions of harvested trees are highest in the tropics, with logs of more than 2 m3 being the rule. Standing trees with crowns routinely weigh more than 20 tonnes before felling and debranching. Dense undergrowth and tree climbers make work even more cumbersome and dangerous.

An increasingly important type of forest in terms of wood production and employment is tree plantations. Tropical plantations are thought to cover about 35 million hectares, with about 2 million hectares added per year (FAO 1995). They usually consist of only one very fast growing species. Increment mostly ranges from 15 to 30 m3/ha/y. Various pines (Pinus spp.) and eucalyptus (Eucalyptus spp.) are the most common species for industrial uses. Plantations are managed intensively and in short rotations (from 6 to 30 years), while most temperate forests take 80, sometimes up to 200 years, to mature. Trees are fairly uniform, and small to medium in size, with approximately 0.05 to 0.5 m3/tree. There is typically little undergrowth.

Prompted by wood scarcity and natural disasters like landslides, floods and avalanches, more and more forests have come under some form of management over the last 500 years. Most industrialized countries apply the “sustained yield principle”, according to which present uses of the forest may not reduce its potential to produce goods and benefits for later generations. Wood utilization levels in most industrialized countries are below the growth rates. This is not true for many tropical countries.

Economic Importance

Globally, wood is by far the most important forest product. World roundwood production is approaching 3.5 billion m3 annually. Wood production grew by 1.6% a year in the 1960s and 1970s and by 1.8% a year in the 1980s, and is projected to increase by 2.1% a year well into the 21st century, with much higher rates in developing countries than in industrialized ones.

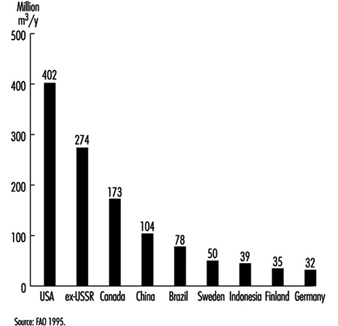

Industrialized countries’ share of world roundwood production is 42% (i.e., roughly proportional to the share of forest area). There is, however, a major difference in the nature of the wood products harvested in industrialized and in developing countries. While in the former more than 85% consists of industrial roundwood to be used for sawnwood, panel or pulp, in the latter 80% is used for fuelwood and charcoal. This is why the list of the ten biggest producers of industrial roundwood in figure 1 includes only four developing countries. Non-wood forest products are still very significant for subsistence in many countries. They account for only 1.5% of traded unprocessed forest products, but products like cork, rattan, resins, nuts and gums are major exports in some countries.

Figure 1. Ten biggest producers of industrial roundwood, 1993 (former USSR 1991).

Worldwide, the value of production in forestry was US$96,000 million in 1991, compared to US$322,000 million in downstream forest-based industries. Forestry alone accounted for 0.4% of world GDP. The share of forestry production in GDP tends to be much higher in developing countries, with an average of 2.2%, than in industrialized ones, where it represents only 0.14% of GDP. In a number of countries forestry is far more important than the averages suggest. In 51 countries the forestry and forest-based industries sector combined generated 5% or more of the respective GDP in 1991.

In several industrialized and developing countries, forest products are a significant export. The total value of forestry exports from developing countries increased from about US$7,000 million in 1982 to over US$19,000 million in 1993 (1996 dollars). Large exporters among industrialized countries include Canada, the United States, Russia, Sweden, Finland and New Zealand. Among tropical countries Indonesia (US$5,000 million), Malaysia (US$4,000 million), Chile and Brazil (about US$2,000 million each) are the most important.

While they cannot be readily expressed in monetary terms, the value of non-commercial goods and benefits generated by forests may well exceed their commercial output. According to estimates, some 140 to 300 million people live in or depend on forests for their livelihood. Forests are also home to three-quarters of all species of living beings. They are a significant sink of carbon dioxide and serve to stabilize climates and water regimes. They reduce erosion, landslides and avalanches, and produce clean drinking water. They are also fundamental for recreation and tourism.

Employment

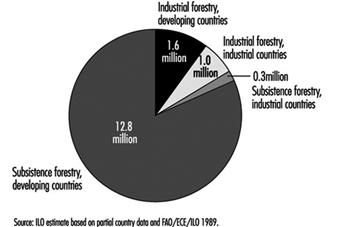

Figures on wage employment in forestry are difficult to obtain and can be unreliable even for industrialized countries. The reasons are the high share of the self-employed and farmers, who do not get recorded in many cases, and the seasonality of many forestry jobs. Statistics in most developing countries simply absorb forestry into the much larger agricultural sector, with no separate figures available. The biggest problem, however, is the fact that most forestry work is not wage employment, but subsistence. The main item here is the production of fuelwood, particularly in developing countries. Bearing these limitations in mind, figure 2 below provides a very conservative estimate of global forestry employment.

Figure 2. Employment in forestry (full-time equivalents).

World wage employment in forestry is in the order of 2.6 million, of which about 1 million is in industrialized countries. This is a fraction of the downstream employment: wood industries and pulp and paper have at least 12 million employees in the formal sector. The bulk of forestry employment is unpaid subsistence work—some 12.8 million full-time equivalents in developing and some 0.3 million in industrialized countries. Total forestry employment can thus be estimated at some 16 million person years. This is equivalent to about 3% of world agricultural employment and to about 1% of total world employment.

In most industrialized countries the size of the forestry workforce has been shrinking. This is a result of a shift from seasonal to full-time, professional forest workers, compounded by rapid mechanization, particularly of wood harvesting. Figure 3 illustrates the enormous differences in productivity in major wood-producing countries. These differences are to some extent due to natural conditions, silvicultural systems and statistical error. Even allowing for these, significant gaps persist. The transformation in the workforce is likely to continue: mechanization is spreading to more countries, and new forms of work organization, namely team work concepts, are boosting productivity, while harvesting levels remain by and large constant. It should be noted that in many countries seasonal and part-time work in forestry are unrecorded, but remain very common among farmers and small woodland owners. In a number of developing countries the industrial forestry workforce is likely to grow as a result of more intensive forest management and tree plantations. Subsistence employment, on the other hand, is likely to decline gradually, as fuelwood is slowly replaced by other forms of energy.

Figure 3. Countries with highest wage employment in forestry and industrial roundwood production (late 1980s to early 1990s).

Characteristics of the Workforce

Industrial forestry work has largely remained a male domain. The proportion of women in the formal workforce rarely exceeds 10%. There are, however, jobs that tend to be predominantly carried out by women, such as planting or tending of young stands and raising seedlings in tree nurseries. In subsistence employment women are a majority in many developing countries, because they are usually responsible for fuelwood gathering.

The largest share of all industrial and subsistence forestry work is related to the harvesting of wood products. Even in human-made forests and plantations, where substantial silvicultural work is required, harvesting accounts for more than 50% of the workdays per hectare. In harvesting in developing countries the ratios of supervisor/technician to foremen and to workers are 1 to 3 and 1 to 40, respectively. The ratio is smaller in most industrialized countries.

Broadly, there are two groups of forestry jobs: those related to silviculture and those related to harvesting. Typical occupations in silviculture include tree planting, fertilization, weed and pest control, and pruning. Tree planting is very seasonal, and in some countries involves a separate group of workers exclusively dedicated to this activity. In harvesting, the most common occupations are chain-saw operation, in tropical forests often with an assistant; choker setters who attach cables to tractors or skylines pulling logs to roadside; helpers who measure, move, load or debranch logs; and machine operators for tractors, loaders, cable cranes, harvesters and logging trucks.

There are major differences between segments of the forestry workforce with respect to the form of employment, which have a direct bearing on their exposure to safety and health hazards. The share of forest workers directly employed by the forest owner or industry has been declining even in those countries where it used to be the rule. More and more work is done through contractors (i.e., relatively small, geographically mobile service firms employed for a particular job). The contractors may be owner-operators (i.e., single-person firms or family businesses) or they have a number of employees. Both the contractors and their employees often have very unstable employment. Under pressure to cut costs in a very competitive market, contractors sometimes resort to illegal practices such as moonlighting and hiring undeclared immigrants. While the move to contracting has in many cases helped to cut costs, to advance mechanization and specialization as well as to adjust the workforce to changing demands, some traditional ailments of the profession have been aggravated through the increased reliance on contract labour. These include accident rates and health complaints, both of which tend to be more frequent among contract labour.

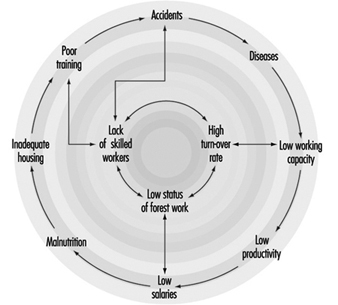

Contract labour has also contributed to further increasing the high rate of turnover in the forestry workforce. Some countries report rates of almost 50% per year for those changing employers and more than 10% per year leaving the forestry sector altogether. This aggravates the skill problem already looming large among much of the forestry workforce. Most skill acquisition is still by experience, usually meaning trial and error. Lack of structured training, and short periods of experience due to high turnover or seasonal work, are major contributing factors to the significant safety and health problems facing the forestry sector (see the article “Skills and training” [FOR15AE] in this chapter).

The dominant wage system in forestry by far continues to be piece-rates (i.e., remuneration solely based on output). Piece-rates tend to lead to a rapid pace of work and are widely believed to increase the number of accidents. There is, however, no scientific evidence to back this contention. One undisputed side effect is that earnings fall once workers have reached a certain age because their physical abilities decline. In countries where mechanization plays a major role, time-based wages have been on the increase, because the work rhythm is largely determined by the machine. Various bonus wage systems are also in use.

Forestry wages are generally well below the industrial average in the same country. Workers, the self-employed and contractors often try to compensate by working 50 or even 60 hours per week. Such situations increase strain on the body and the risk of accidents because of fatigue.

Organized labour and trade unions are rather rare in the forestry sector. The traditional problems of organizing geographically dispersed, mobile, sometimes seasonal workers have been compounded by the fragmentation of the workforce into small contractor firms. At the same time, the number of workers in categories that are typically unionized, such as those directly employed in larger forest enterprises, is falling steadily. Labour inspectorates attempting to cover the forestry sector are faced with problems similar in nature to those of trade union organizers. As a result there is very little inspection in most countries. In the absence of institutions whose mission is to protect worker rights, forest workers often have little knowledge of their rights, including those laid down in existing safety and health regulations, and experience great difficulties in exercising such rights.

Health and Safety Problems

The popular notion in many countries is that forestry work is a 3-D job: dirty, difficult and dangerous. A host of natural, technical and organizational factors contribute to that reputation. Forestry work has to be done outdoors. Workers are thus exposed to the extremes of weather: heat, cold, snow, rain and ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Work even often proceeds in bad weather and, in mechanized operations, it increasingly continues at night. Workers are exposed to natural hazards such as broken terrain or mud, dense vegetation and a series of biological agents.

Worksites tend to be remote, with poor communication and difficulties in rescue and evacuation. Life in camps with extended periods of isolation from family and friends is still common in many countries.

The difficulties are compounded by the nature of the work—trees may fall unpredictably, dangerous tools are used and often there is a heavy physical workload. Other factors like work organization, employment patterns and training also play a significant role in increasing or reducing hazards associated with forestry work. In most countries the net result of the above influences are very high accident risks and serious health problems.

Fatalities in Forest Work

In most countries forest work is one of the most dangerous occupations, with great human and financial losses. In the United States accident insurance costs amount to 40% of payroll.

A cautious interpretation of the available evidence suggests that accident trends are more often upward than downward. Encouragingly, there are countries that have a long-standing record in bringing down accident frequencies (e.g., Sweden and Finland). Switzerland represents the more common situation of increasing, or at best stagnating, accident rates. The scarce data available for developing countries indicate little improvement and usually excessively high accident levels. A study of safety in pulpwood logging in plantation forests in Nigeria, for example, found that on average a worker had 2 accidents per year. Between 1 in 4 and 1 in 10 workers suffered a serious accident in a given year (Udo 1987).

A closer inspection of accidents reveals that harvesting is far more hazardous than other forest operations (ILO 1991). Within forest harvesting, tree felling and cross-cutting are the jobs with the most accidents, particularly serious or fatal ones. In some countries, such as in the Mediterranean area, firefighting can also be a major cause of fatalities, claiming up to 13 lives a year in Spain in some years (Rodero 1987). Road transport can also account for a large share of serious accidents, particularly in tropical countries.

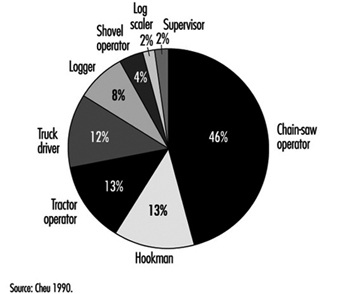

The chain-saw is clearly the single most dangerous tool in forestry, and the chain-saw operator the most exposed worker. The situation depicted in figure 4 for a territory of Malaysia is found with minor variations in most other countries as well. In spite of increasing mechanization, the chain-saw is likely to remain the key problem in industrialized countries. In developing countries, its use can be expected to expand as plantations account for an increasing share of the wood harvest.

Figure 4. Distribution of logging fatalities among jobs, Malaysia (Sarawak), 1989.

Virtually all parts of the body can be injured in forest work, but there tends to be a concentration of injuries to the legs, feet, back and hands, in roughly that order. Cuts and open wounds are the most common type of injury in chain-saw work while bruises dominate in skidding, but there are also fractures and dislocations.

Two situations under which the already high risk of serious accidents in forest harvesting multiplies severalfold are “hung-up” trees and wind-blown timber. Windblow tends to produce timber under tension, which requires specially adapted cutting techniques (for guidance see FAO/ECE/ILO 1996a; FAO/ILO 1980; and ILO 1998). Hung-up trees are those that have been severed from the stump but did not fall to the ground because the crown became entangled with other trees. Hung-up trees are extremely dangerous and referred to as “widow-makers” in some countries, because of the high number of fatalities they cause. Aid tools, such as turning hooks and winches, are required to bring such trees down safely. In no case should it be permitted that other trees be felled onto a hung-up one in the hope of bringing it down. This practice, known as “driving” in some countries, is extremely hazardous.

Accident risks vary not only with technology and exposure due to the job, but with other factors as well. In almost all cases for which data are available, there is a very significant difference between segments of the workforce. Full-time, professional forest workers directly employed by a forest enterprise are far less affected than farmers, self-employed or contract labour. In Austria, farmers seasonally engaged in logging suffer twice as many accidents per million cubic metres harvested as professional workers (Sozialversicherung der Bauern 1990), in Sweden, even four times as many. In Switzerland, workers employed in public forests have only half as many accidents as those employed by contractors, particularly where workers are hired only seasonally and in the case of migrant labour (Wettmann 1992).

The increasing mechanization of tree harvesting has had very positive consequences for work safety. Machine operators are well protected in guarded cabins, and accident risks have dropped very significantly. Machine operators experience less than 15% of the accidents of chain-saw operators to harvest the same amount of timber. In Sweden operators have one-quarter of the accidents of professional chain-saw operators.

Growing Occupational Disease Problems

The reverse side of the mechanization coin is an emerging problem of neck and shoulder strain injuries among machine operators. These can be as incapacitating as serious accidents.

The above problems add to the traditional health complaints of chain-saw operators—namely, back injuries and hearing loss. Back pain due to physically heavy work and unfavourable working postures is very common among chain-saw operators and workers doing manual loading of logs. There is a high incidence of premature loss of working capacity and of early retirement among forest workers as a result. A traditional ailment of chain-saw operators that has largely been overcome in recent years through improved saw design is vibration-induced “white finger” disease.

The physical, chemical and biological hazards causing health problems in forestry are discussed in the following articles of this chapter.

Special Risks for Women

Safety risks are by and large the same for men and women in forestry. Women are often involved in planting and tending work, including the application of pesticides. However, women who have smaller body size, lung volume, heart and muscles may have a work capacity on average that is about one-third lower than that of men. Correspondingly, legislation in many countries limits the weight to be lifted and carried by women to about 20 kg (ILO 1988), although such sex-based differences in exposure limits are illegal in many countries. These limits are often exceeded by women working in forestry. Studies in British Columbia, where separate standards do not apply, among planting workers showed full loads of plants carried by men and women to average 30.5 kg, often in steep terrain with heavy ground cover (Smith 1987).

Excessive loads are also common in many developing countries where women work as fuelwood carriers. A survey in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, for example, found that an estimated 10,000 women and children eke out a livelihood from hauling fuelwood into town on their backs (see figure 5 ). The average bundle weighs 30 kg and is carried over a distance of 10 km. The work is highly debilitating and results in numerous serious health complaints, including frequent miscarriages (Haile 1991).

Figure 5. Woman fuelwood carrier, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

The relationship between the specific working conditions in forestry, workforce characteristics, form of employment, training and other similar factors and safety and health in the sector has been a recurrent theme of this introductory article. In forestry, even more than in other sectors, safety and health cannot be analysed, let alone promoted, in isolation. This theme will also be the leitmotiv for the remainder of the chapter.

Hops

Hops are used in brewing and are commonly grown in the Pacific Northwest of the United States, Europe (especially Germany and the United Kingdom), Australia and New Zealand.

Hops grow from rhizome cuttings of female hop plants. Hop vines grow up to 4.5 to 7.5 m or more during the growing season. These vines are trained to climb up heavy trellis wire or heavy cords. Hops are traditionally spaced 2 m apart in each direction with two cords per plant going to the overhead trellis wire at about 45° angles. Trellises are about 5.5 m high and are made from 10 ´ 10 cm pressure-treated timbers or poles sunk 0.6 to 1 m into the ground.

Manual labour is used to train the vines after the vines reach about a third of a metre in length; additionally, the lowest metre is pruned to allow air circulation to reduce disease development.

Hops vines are harvested in the fall. In the United Kingdom, some hops are grown in trellises 3 m high and harvested with an over-the-row mechanical harvester. In the United States, hop combines are available to harvest 5.5-m-high trellises. The areas that the harvesters (field strippers) are unable to get are harvested by hand with a machete. Newly harvested hops are then kiln dried from 80% moisture to about 10%. Hops are cooled, then baled and taken to cold storage for end use.

Safety Concerns

Workers need to wear long sleeves and gloves when working near the vines, because hooked hairs of the plant may cause a rash on the skin. Some individuals become more sensitized to the vines than others.

A majority of the injuries involve strains and sprains due to lifting materials such as irrigation pipes and bales, and over-reaching when working on trellises. Workers should be trained in lifting or mechanical aids should be used.

Workers need to wear chaps at the knee and below to protect the leg from cuts while cutting the vines by hand. Eye protection is a must while working with the vines.

Many injuries occur while workers tie twine to the wire trellis wire. Most work is performed while standing on high trailers or platforms on tractors. Accidents have been reduced by providing safety belts or guard rails to prevent falls, and by wearing eye protection. Because there is much movement with the hands, carpal tunnel syndrome may be a problem.

Since hops are often treated with fungicides during the season, proper posting of re-entry intervals is needed.

Worker’s compensation claims in Washington State (US) tend to indicate that injury incidence ranges between 30 and 40 injuries per 100 person years worked. Growers through their association have safety committees that actively work to lower injury rates. Injury rates in Washington are similar to those found in the tree fruit industry and dairy. Highest injury incidence tends to occur in August and September.

The industry has unique practices in the production of the product, where much of the machinery and equipment is locally manufactured. By the vigilance of the safety committees to provide adequate machine guarding, they are able to reduce “caught in” type injuries within the harvesting and processing operations. Training should focus on proper use of knives, PPE and prevention of falls from vehicles and other machines.

Wood Harvesting

The present article draws heavily on two publications: FAO 1996 and FAO/ILO 1980. This article is an overview; numerous other references are available. For specific guidance on preventive measures, see ILO 1998.

Wood harvesting is the preparation of logs in a forest or tree plantation according to the requirements of a user, and delivery of logs to a consumer. It includes the cutting of trees, their conversion into logs, extraction and long distance transport to a consumer or processing plant. The terms forest harvesting, wood harvesting or logging are often used synonymously. Long-distance transport and the harvesting of non-wood forest products are dealt with in separate articles in this chapter.

Operations

While many different methods are used for wood harvesting, they all involve a similar sequence of operations:

- tree felling: severing a tree from the stump and bringing it down

- topping and debranching (delimbing): cutting off the unusable tree crown and the branches

- debarking: removing the bark from the stem; this operation is often done at the processing plant rather than in the forest; in fuelwood harvesting it is not done at all

- extraction: moving the stems or logs from the stump to a place close to a forest road where they can be sorted, piled and often stored temporarily, awaiting long distance transport

- log making/cross-cutting (bucking): cutting the stem to the length specified by the intended use of the log

- scaling: determining the quantity of logs produced, usually by measuring volume (for small dimension timber also by weight; the latter is common for pulpwood; weighing is done at the processing plant in that case)

- sorting, piling and temporary storage: logs are usually of variable dimensions and quality, and are therefore classified into assortments according to their potential use as pulpwood, sawlogs and so on, and piled until a full load, usually a truckload, has been assembled; the cleared area where these operations, as well as scaling and loading, take place is called a “landing”

- loading: moving the logs onto the transport medium, typically a truck, and attaching the load.

These operations are not necessarily carried out in the above sequence. Depending on the forest type, the kind of product desired and the technology available, it may be more advantageous to carry out an operation either earlier (i.e., closer to the stump) or later (i.e., at the landing or even at the processing plant). One common classification of harvesting methods is based on distinguishing between:

- full-tree systems, where trees are extracted to the roadside, the landing or the processing plant with the full crown

- short-wood systems, where topping, debranching and cross-cutting is done close to the stump (logs are usually not longer than 4 to 6 m)

- tree-length systems, where tops and branches are removed before extraction.

The most important group of harvesting methods for industrial wood is based on tree length. Short-wood systems are standard in northern Europe and also common for small-dimension timber and fuelwood in many other parts of the world. Their share is likely to increase. Full-tree systems are the least common in industrial wood harvesting, and are used in only a limited number of countries (e.g., Canada, the Russian Federation and the United States). There they account for less than 10% of volume. The importance of this method is diminishing.

For work organization, safety analysis and inspection, it is useful to conceive of three distinct work areas in a wood harvesting operation:

- the felling site or stump

- the forest terrain between the stump and the forest road

- the landing.

It is also worthwhile to examine whether the operations take place largely independently in space and time or whether they are closely related and interdependent. The latter is often the case in harvesting systems where all steps are synchronized. Any disturbance thus disrupts the entire chain, from felling to transport. These so-called hot-logging systems can create extra pressure and strain if not carefully balanced.

The stage in the life cycle of a forest during which wood harvesting takes place, and the harvesting pattern, will affect both the technical process and its associated hazards. Wood harvesting occurs either as thinning or as final cut. Thinning is the removal of some, usually undesirable, trees from a young stand to improve the growth and quality of the remaining trees. It is usually selective (i.e., individual trees are removed without creating major gaps). The spatial pattern generated is similar to that in selective final cutting. In the latter case, however, the trees are mature and often large. Even so, only some of the trees are removed and a significant tree cover remains. In both cases orientation on the worksite is difficult because remaining trees and vegetation block the view. It can be very difficult to bring trees down because their crowns tend to be intercepted by the crowns of remaining trees. There is a high risk of falling debris from the crowns. Both situations are difficult to mechanize. Thinning and selective cutting therefore require more planning and skill to be done safely.

The alternative to selective felling for final harvest is the removal of all trees from a site, called “clear cutting”. Clearcuts can be small, say 1 to 5 hectares, or very large, covering several square kilometres. Large clearcuts are severely criticized on environmental and scenic grounds in many countries. Whatever the pattern of the cut, harvesting old growth and natural forest usually involves greater risk than harvesting younger stands or human-made forests because trees are large and have tremendous inertia when falling. Their branches may be intertwined with the crowns of other trees and climbers, causing them to break off branches of other trees as they fall. Many trees are dead or have internal rot which may not be apparent until late in the felling process. Their behaviour during felling is often unpredictable. Rotten trees may break off and fall in unexpected directions. Unlike green trees, dead and dry trees, called snags in North America, fall quickly.

Technological developments

Technological development in wood harvesting has been very rapid over the second half of the 20th century. Average productivity has been soaring in the process. Today, many different harvesting methods are in use, sometimes side by side in the same country. An overview of systems in use in Germany in the mid-1980s, for example, describes almost 40 different configurations of equipment and methods (Dummel and Branz 1986).

While some harvesting methods are technologically far more complex than others, no single method is inherently superior. The choice will usually depend on the customer specifications for the logs, on forest conditions and terrain, on environmental considerations, and often decisively on cost. Some methods are also technically limited to small and medium-size trees and relatively gentle terrain, with slopes not exceeding 15 to 20°.

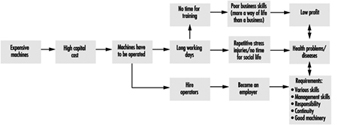

Cost and performance of a harvesting system can vary over a wide range, depending on how well the system fits the conditions of the site and, equally important, on the skill of the workers and how well the operation is organized. Hand tools and manual extraction, for example, make perfect economic and social sense in countries with high unemployment, low labour and high capital cost, or in small-scale operations. Fully mechanized methods can achieve very high daily outputs but involve large capital investments. Modern harvesters under favourable conditions can produce upwards of 200 m3 of logs per 8-hour day. A chain-saw operator is unlikely to produce more than 10% of that. A harvester or big cable yarder costs around US$500,000 compared to US$1,000 to US$2,000 for a chain-saw and US$200 for a good quality cross-cut handsaw.

Common Methods, Equipment and Hazards

Felling and preparation for extraction

This stage includes felling and removal of crown and branches; it may include debarking, cross-cutting and scaling. It is one of the most hazardous industrial occupations. Hand tools and chain-saws or machines are used in felling and debranching trees and crosscutting trees into logs. Hand tools include cutting tools such as axes, splitting hammers, bush hooks and bush knives, and hand saws such as cross-cut saws and bow saws. Chain-saws are widely used in most countries. In spite of major efforts and progress by regulators and manufacturers to improve chain-saws, they remain the single most dangerous type of machine in forestry. Most serious accidents and many health problems are associated with their use.

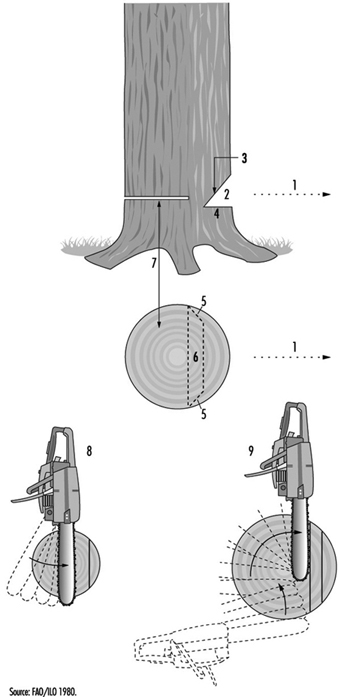

The first activity to be carried out is felling, or severing the tree from the stump as close to the ground as conditions permit. The lower part of the stem is typically the most valuable part, as it contains a high volume, and has no knots and an even wood texture. It should therefore not split, and no fibre should be torn out from the butt. Controlling the direction of the fall is important, not only to protect the tree and those to be left standing, but also to protect the workers and to make extraction easier. In manual felling, this control is achieved by a special sequence and configuration of cuts.