Children categories

36. Barometric Pressure Increased (2)

36. Barometric Pressure Increased

Chapter Editor: T.J.R. Francis

Table of Contents

Working under Increased Barometric Pressure

Eric Kindwall

Dees F. Gorman

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Instructions for compressed-air workers

2. Decompression illness: Revised classification

37. Barometric Pressure Reduced (4)

37. Barometric Pressure Reduced

Chapter Editor: Walter Dümmer

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Ventilatory Acclimatization to High Altitude

John T. Reeves and John V. Weil

Physiological Effects of Reduced Barometric Pressure

Kenneth I. Berger and William N. Rom

Health Considerations for Managing Work at High Altitudes

John B. West

Prevention of Occupational Hazards at High Altitudes

Walter Dümmer

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

38. Biological Hazards (4)

38. Biological Hazards

Chapter Editor: Zuheir Ibrahim Fakhri

Table of Contents

Tables

Workplace Biohazards

Zuheir I. Fakhri

Aquatic Animals

D. Zannini

Terrestrial Venomous Animals

J.A. Rioux and B. Juminer

Clinical Features of Snakebite

David A. Warrell

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Occupational settings with biological agents

2. Viruses, bacteria, fungi & plants in the workplace

3. Animals as a source of occupational hazards

39. Disasters, Natural and Technological (12)

39. Disasters, Natural and Technological

Chapter Editor: Pier Alberto Bertazzi

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Disasters and Major Accidents

Pier Alberto Bertazzi

ILO Convention concerning the Prevention of Major Industrial Accidents, 1993 (No. 174)

Disaster Preparedness

Peter J. Baxter

Post-Disaster Activities

Benedetto Terracini and Ursula Ackermann-Liebrich

Weather-Related Problems

Jean French

Avalanches: Hazards and Protective Measures

Gustav Poinstingl

Transportation of Hazardous Material: Chemical and Radioactive

Donald M. Campbell

Radiation Accidents

Pierre Verger and Denis Winter

Case Study: What does dose mean?

Occupational Health and Safety Measures in Agricultural Areas Contaminated by Radionuclides: The Chernobyl Experience

Yuri Kundiev, Leonard Dobrovolsky and V.I. Chernyuk

Case Study: The Kader Toy Factory Fire

Casey Cavanaugh Grant

Impacts of Disasters: Lessons from a Medical Perspective

José Luis Zeballos

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Definitions of disaster types

2. 25-yr average # victims by type & region-natural trigger

3. 25-yr average # victims by type & region-non-natural trigger

4. 25-yr average # victims by type-natural trigger (1969-1993)

5. 25-yr average # victims by type-non-natural trigger (1969-1993)

6. Natural trigger from 1969 to 1993: Events over 25 years

7. Non-natural trigger from 1969 to 1993: Events over 25 years

8. Natural trigger: Number by global region & type in 1994

9. Non-natural trigger: Number by global region & type in 1994

10. Examples of industrial explosions

11. Examples of major fires

12. Examples of major toxic releases

13. Role of major hazard installations management in hazard control

14. Working methods for hazard assessment

15. EC Directive criteria for major hazard installations

16. Priority chemicals used in identifying major hazard installations

17. Weather-related occupational risks

18. Typical radionuclides, with their radioactive half-lives

19. Comparison of different nuclear accidents

20. Contamination in Ukraine, Byelorussia & Russia after Chernobyl

21. Contamination strontium-90 after the Khyshtym accident (Urals 1957)

22. Radioactive sources that involved the general public

23. Main accidents involving industrial irradiators

24. Oak Ridge (US) radiation accident registry (worldwide, 1944-88)

25. Pattern of occupational exposure to ionizing radiation worldwide

26. Deterministic effects: thresholds for selected organs

27. Patients with acute irradiation syndrome (AIS) after Chernobyl

28. Epidemiological cancer studies of high dose external irradiation

29. Thyroid cancers in children in Belarus, Ukraine & Russia, 1981-94

30. International scale of nuclear incidents

31. Generic protective measures for general population

32. Criteria for contamination zones

33. Major disasters in Latin America & the Caribbean, 1970-93

34. Losses due to six natural disasters

35. Hospitals & hospital beds damaged/ destroyed by 3 major disasters

36. Victims in 2 hospitals collapsed by the 1985 earthquake in Mexico

37. Hospital beds lost resulting from the March 1985 Chilean earthquake

38. Risk factors for earthquake damage to hospital infrastructure

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Click to return to top of page

40. Electricity (3)

40. Electricity

Chapter Editor: Dominique Folliot

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Electricity—Physiological Effects

Dominique Folliot

Static Electricity

Claude Menguy

Prevention And Standards

Renzo Comini

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Estimates of the rate of electrocution-1988

2. Basic relationships in electrostatics-Collection of equations

3. Electron affinities of selected polymers

4. Typical lower flammability limits

5. Specific charge associated with selected industrial operations

6. Examples of equipment sensitive to electrostatic discharges

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

41. Fire (6)

41. Fire

Chapter Editor: Casey C. Grant

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Basic Concepts

Dougal Drysdale

Sources of Fire Hazards

Tamás Bánky

Fire Prevention Measures

Peter F. Johnson

Passive Fire Protection Measures

Yngve Anderberg

Active Fire Protection Measures

Gary Taylor

Organizing for Fire Protection

S. Dheri

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Lower & upper flammability limits in air

2. Flashpoints & firepoints of liquid & solid fuels

3. Ignition sources

4. Comparison of concentrations of different gases required for inerting

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

42. Heat and Cold (12)

42. Heat and Cold

Chapter Editor: Jean-Jacques Vogt

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

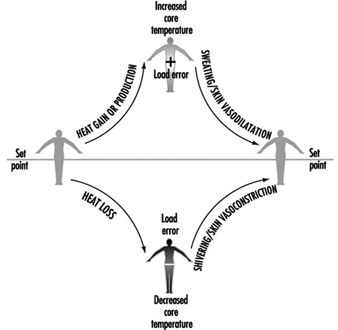

Physiological Responses to the Thermal Environment

W. Larry Kenney

Effects of Heat Stress and Work in the Heat

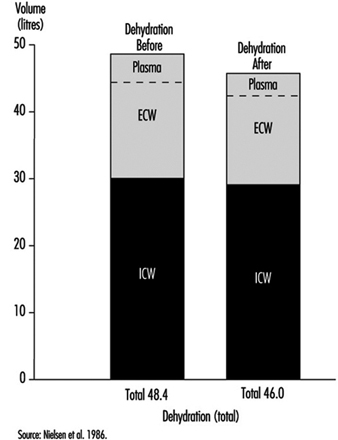

Bodil Nielsen

Heat Disorders

Tokuo Ogawa

Prevention of Heat Stress

Sarah A. Nunneley

The Physical Basis of Work in Heat

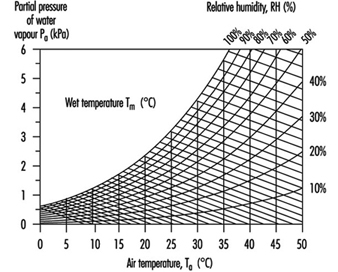

Jacques Malchaire

Assessment of Heat Stress and Heat Stress Indices

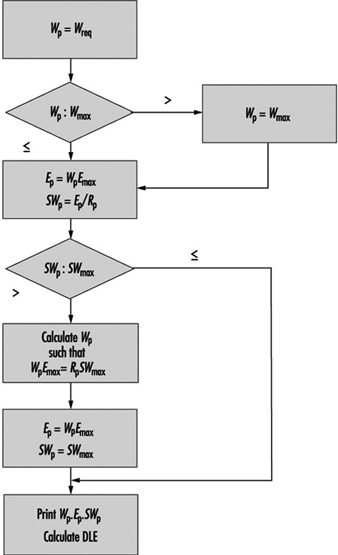

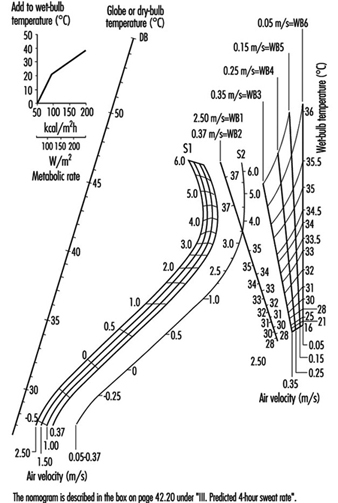

Kenneth C. Parsons

Case Study: Heat Indices: Formulae and Definitions

Heat Exchange through Clothing

Wouter A. Lotens

Cold Environments and Cold Work

Ingvar Holmér, Per-Ola Granberg and Goran Dahlstrom

Prevention of Cold Stress in Extreme Outdoor Conditions

Jacques Bittel and Gustave Savourey

Cold Indices and Standards

Ingvar Holmér

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Electrolyte concentration in blood plasma & sweat

2. Heat Stress Index & Allowable Exposure Times: calculations

3. Interpretation of Heat Stress Index values

4. Reference values for criteria of thermal stress & strain

5. Model using heart rate to assess heat stress

6. WBGT reference values

7. Working practices for hot environments

8. Calculation of the SWreq index & assessment method: equations

9. Description of terms used in ISO 7933 (1989b)

10. WBGT values for four work phases

11. Basic data for the analytical assessment using ISO 7933

12. Analytical assessment using ISO 7933

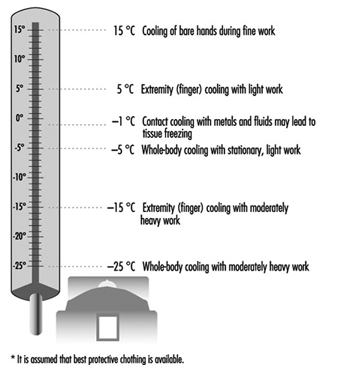

13. Air temperatures of various cold occupational environments

14. Duration of uncompensated cold stress & associated reactions

15. Indication of anticipated effects of mild & severe cold exposure

16. Body tissue temperature & human physical performance

17. Human responses to cooling: Indicative reactions to hypothermia

18. Health recommendations for personnel exposed to cold stress

19. Conditioning programmes for workers exposed to cold

20. Prevention & alleviation of cold stress: strategies

21. Strategies & measures related to specific factors & equipment

22. General adaptational mechanisms to cold

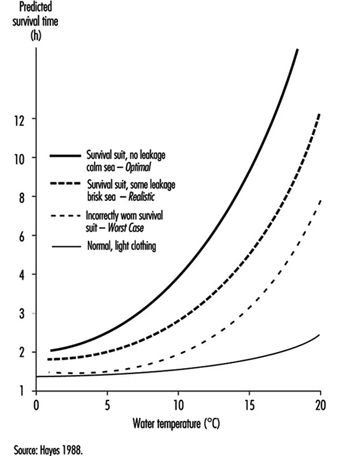

23. Number of days when water temperature is below 15 ºC

24. Air temperatures of various cold occupational environments

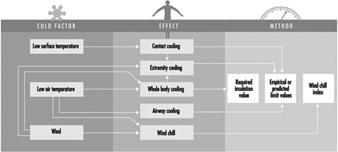

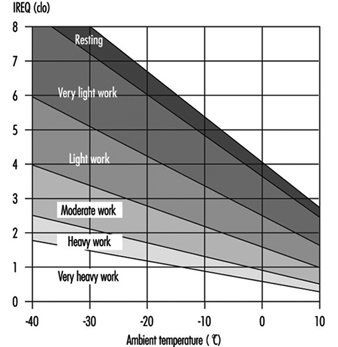

25. Schematic classification of cold work

26. Classification of levels of metabolic rate

27. Examples of basic insulation values of clothing

28. Classification of thermal resistance to cooling of handwear

29. Classification of contact thermal resistance of handwear

30. Wind Chill Index, temperature & freezing time of exposed flesh

31. Cooling power of wind on exposed flesh

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

43. Hours of Work (1)

43. Hours of Work

Chapter Editor: Peter Knauth

Table of Contents

Hours of Work

Peter Knauth

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Time intervals from beginning shiftwork until three illnesses

2. Shiftwork & incidence of cardiovascular disorders

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

44. Indoor Air Quality (8)

44. Indoor Air Quality

Chapter Editor: Xavier Guardino Solá

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Indoor Air Quality: Introduction

Xavier Guardino Solá

Nature and Sources of Indoor Chemical Contaminants

Derrick Crump

Radon

María José Berenguer

Tobacco Smoke

Dietrich Hoffmann and Ernst L. Wynder

Smoking Regulations

Xavier Guardino Solá

Measuring and Assessing Chemical Pollutants

M. Gracia Rosell Farrás

Biological Contamination

Brian Flannigan

Regulations, Recommendations, Guidelines and Standards

María José Berenguer

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Classification of indoor organic pollutants

2. Formaldehyde emission from a variety of materials

3. Ttl. volatile organic comp’ds concs, wall/floor coverings

4. Consumer prods & other sources of volatile organic comp’ds

5. Major types & concentrations in the urban United Kingdom

6. Field measurements of nitrogen oxides & carbon monoxide

7. Toxic & tumorigenic agents in cigarette sidestream smoke

8. Toxic & tumorigenic agents from tobacco smoke

9. Urinary cotinine in non-smokers

10. Methodology for taking samples

11. Detection methods for gases in indoor air

12. Methods used for the analysis of chemical pollutants

13. Lower detection limits for some gases

14. Types of fungus which can cause rhinitis and/or asthma

15. Micro-organisms and extrinsic allergic alveolitis

16. Micro-organisms in nonindustrial indoor air & dust

17. Standards of air quality established by the US EPA

18. WHO guidelines for non-cancer and non-odour annoyance

19. WHO guideline values based on sensory effects or annoyance

20. Reference values for radon of three organizations

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

45. Indoor Environmental Control (6)

45. Indoor Environmental Control

Chapter Editor: Juan Guasch Farrás

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Control of Indoor Environments: General Principles

A. Hernández Calleja

Indoor Air: Methods for Control and Cleaning

E. Adán Liébana and A. Hernández Calleja

Aims and Principles of General and Dilution Ventilation

Emilio Castejón

Ventilation Criteria for Nonindustrial Buildings

A. Hernández Calleja

Heating and Air-Conditioning Systems

F. Ramos Pérez and J. Guasch Farrás

Indoor Air: Ionization

E. Adán Liébana and J. Guasch Farrás

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Most common indoor pollutants & their sources

2. Basic requirements-dilution ventilation system

3. Control measures & their effects

4. Adjustments to working environment & effects

5. Effectiveness of filters (ASHRAE standard 52-76)

6. Reagents used as absorbents for contaminents

7. Levels of quality of indoor air

8. Contamination due to the occupants of a building

9. Degree of occupancy of different buildings

10. Contamination due to the building

11. Quality levels of outside air

12. Proposed norms for environmental factors

13. Temperatures of thermal comfort (based on Fanger)

14. Characteristics of ions

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

46. Lighting (3)

46. Lighting

Chapter Editor: Juan Guasch Farrás

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Types of Lamps and Lighting

Richard Forster

Conditions Required for Visual

Fernando Ramos Pérez and Ana Hernández Calleja

General Lighting Conditions

N. Alan Smith

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Improved output & wattage of some 1,500 mm fluorescent tube lamps

2. Typical lamp efficacies

3. International Lamp Coding System (ILCOS) for some lamp types

4. Common colours & shapes of incandescent lamps & ILCOS codes

5. Types of high-pressure sodium lamp

6. Colour contrasts

7. Reflection factors of different colours & materials

8. Recommended levels of maintained illuminance for locations/tasks

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

47. Noise (5)

47. Noise

Chapter Editor: Alice H. Suter

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

The Nature and Effects of Noise

Alice H. Suter

Noise Measurement and Exposure Evaluation

Eduard I. Denisov and German A. Suvorov

Engineering Noise Control

Dennis P. Driscoll

Hearing Conservation Programmes

Larry H. Royster and Julia Doswell Royster

Standards and Regulations

Alice H. Suter

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Permissible exposure limits (PEL)for noise exposure, by nation

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

48. Radiation: Ionizing (6)

48. Radiation: Ionizing

Chapter Editor: Robert N. Cherry, Jr.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Robert N. Cherry, Jr.

Radiation Biology and Biological Effects

Arthur C. Upton

Sources of Ionizing Radiation

Robert N. Cherry, Jr.

Workplace Design for Radiation Safety

Gordon M. Lodde

Radiation Safety

Robert N. Cherry, Jr.

Planning for and Management of Radiation Accidents

Sydney W. Porter, Jr.

49. Radiation, Non-Ionizing (9)

49. Radiation, Non-Ionizing

Chapter Editor: Bengt Knave

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Electric and Magnetic Fields and Health Outcomes

Bengt Knave

The Electromagnetic Spectrum: Basic Physical Characteristics

Kjell Hansson Mild

Ultraviolet Radiation

David H. Sliney

Infrared Radiation

R. Matthes

Light and Infrared Radiation

David H. Sliney

Lasers

David H. Sliney

Radiofrequency Fields and Microwaves

Kjell Hansson Mild

VLF and ELF Electric and Magnetic Fields

Michael H. Repacholi

Static Electric and Magnetic Fields

Martino Grandolfo

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Sources and exposures for IR

2. Retinal thermal hazard function

3. Exposure limits for typical lasers

4. Applications of equipment using range >0 to 30 kHz

5. Occupational sources of exposure to magnetic fields

6. Effects of currents passing through the human body

7. Biological effects of various current density ranges

8. Occupational exposure limits-electric/magnetic fields

9. Studies on animals exposed to static electric fields

10. Major technologies and large static magnetic fields

11. ICNIRP recommendations for static magnetic fields

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

50. Vibration (4)

50. Vibration

Chapter Editor: Michael J. Griffin

Table of Contents

Table and Figures

Vibration

Michael J. Griffin

Whole-body Vibration

Helmut Seidel and Michael J. Griffin

Hand-transmitted Vibration

Massimo Bovenzi

Motion Sickness

Alan J. Benson

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Activities with adverse effects of whole-body vibration

2. Preventive measures for whole-body vibration

3. Hand-transmitted vibration exposures

4. Stages, Stockholm Workshop scale, hand-arm vibration syndrome

5. Raynaud’s phenomenon & hand-arm vibration syndrome

6. Threshold limit values for hand-transmitted vibration

7. European Union Council Directive: Hand-transmitted vibration (1994)

8. Vibration magnitudes for finger blanching

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

51. Violence (1)

51. Violence

Chapter Editor: Leon J. Warshaw

Table of Contents

Violence in the Workplace

Leon J. Warshaw

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Highest rates of occupational homicide, US workplaces, 1980-1989

2. Highest rates of occupational homicide US occupations, 1980-1989

3. Risk factors for workplace homicides

4. Guides for programmes to prevent workplace violence

52. Visual Display Units (11)

52. Visual Display Units

Chapter Editor: Diane Berthelette

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Overview

Diane Berthelette

Characteristics of Visual Display Workstations

Ahmet Çakir

Ocular and Visual Problems

Paule Rey and Jean-Jacques Meyer

Reproductive Hazards - Experimental Data

Ulf Bergqvist

Reproductive Effects - Human Evidence

Claire Infante-Rivard

Case Study: A Summary of Studies of Reproductive Outcomes

Musculoskeletal Disorders

Gabriele Bammer

Skin Problems

Mats Berg and Sture Lidén

Psychosocial Aspects of VDU Work

Michael J. Smith and Pascale Carayon

Ergonomic Aspects of Human - Computer Interaction

Jean-Marc Robert

Ergonomics Standards

Tom F.M. Stewart

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Distribution of computers in various regions

2. Frequency & importance of elements of equipment

3. Prevalence of ocular symptoms

4. Teratological studies with rats or mice

5. Teratological studies with rats or mice

6. VDU use as a factor in adverse pregnancy outcomes

7. Analyses to study causes musculoskeletal problems

8. Factors thought to cause musculoskeletal problems

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Passive Fire Protection Measures

Confining Fires by Compartmentation

Building and site planning

Fire safety engineering work should begin early in the design phase because the fire safety requirements influence the layout and design of the building considerably. In this way, the designer can incorporate fire safety features into the building much better and more economically. The overall approach includes consideration of both interior building functions and layout, as well as exterior site planning. Prescriptive code requirements are more and more replaced by functionally based requirements, which means there is an increased demand for experts in this field. From the beginning of the construction project, the building designer therefore should contact fire experts to elucidate the following actions:

- to describe the fire problem specific to the building

- to describe different alternatives to obtain the required fire safety level

- to analyse system choice regarding technical solutions and economy

- to create presumptions for technical optimized system choices.

The architect must utilize a given site in designing the building and adapt the functional and engineering considerations to the particular site conditions that are present. In a similar manner, the architect should consider site features in arriving at decisions on fire protection. A particular set of site characteristics may significantly influence the type of active and passive protection suggested by the fire consultant. Design features should consider the local fire-fighting resources that are available and the time to reach the building. The fire service cannot and should not be expected to provide complete protection for building occupants and property; it must be assisted by both active and passive building fire defences, to provide reasonable safety from the effects of fire. Briefly, the operations may be broadly grouped as rescue, fire control and property conservation. The first priority of any fire-fighting operation is to ensure that all occupants are out of the building before critical conditions occur.

Structural design based on classification or calculation

A well-established means of codifying fire protection and fire safety requirements for buildings is to classify them by types of construction, based upon the materials used for the structural elements and the degree of fire resistance afforded by each element. Classification can be based on furnace tests in accordance with ISO 834 (fire exposure is characterized by the standard temperature-time curve), combination of test and calculation or by calculation. These procedures will identify the standard fire resistance (the ability to fulfil required functions during 30, 60, 90 minutes, etc.) of a structural load-bearing and/or separating member. Classification (especially when based on tests) is a simplified and conservative method and is more and more replaced by functionally based calculation methods taking into account the effect of fully developed natural fires. However, fire tests will always be required, but they can be designed in a more optimal way and be combined with computer simulations. In that procedure, the number of tests can be reduced considerably. Usually, in the fire test procedures, load-bearing structural elements are loaded to 100% of the design load, but in real life the load utilization factor is most often less than that. Acceptance criteria are specific for the construction or element tested. Standard fire resistance is the measured time the member can withstand the fire without failure.

Optimum fire engineering design, balanced against anticipated fire severity, is the objective of structural and fire protection requirements in modern performance-based codes. These have opened the way for fire engineering design by calculation with prediction of the temperature and structural effect due to a complete fire process (heating and subsequent cooling is considered) in a compartment. Calculations based on natural fires mean that the structural elements (important for the stability of the building) and the whole structure are not allowed to collapse during the entire fire process, including cool down.

Comprehensive research has been performed during the past 30 years. Various computer models have been developed. These models utilize basic research on mechanical and thermal properties of materials at elevated temperatures. Some computer models are validated against a vast number of experimental data, and a good prediction of structural behaviour in fire is obtained.

Compartmentation

A fire compartment is a space within a building extending over one or several floors which is enclosed by separating members such that the fire spread beyond the compartment is prevented during the relevant fire exposure. Compartmentation is important in preventing the fire to spread into too large spaces or into the whole building. People and property outside the fire compartment can be protected by the fact that the fire is extinguished or burns out by itself or by the delaying effect of the separating members on the spread of fire and smoke until the occupants are rescued to a place of safety.

The fire resistance required by a compartment depends upon its intended purpose and on the expected fire. Either the separating members enclosing the compartment shall resist the maximum expected fire or contain the fire until occupants are evacuated. The load-bearing elements in the compartment must always resist the complete fire process or be classified to a certain resistance measured in terms of periods of time, which is equal or longer than the requirement of the separating members.

Structural integrity during a fire

The requirement for maintaining structural integrity during a fire is the avoidance of structural collapse and the ability of the separating members to prevent ignition and flame spread into adjacent spaces. There are different approaches to provide the design for fire resistance. They are classifications based on standard fire-resistance test as in ISO 834, combination of test and calculation or solely calculation and the performance-based procedure computer prediction based on real fire exposure.

Interior finish

Interior finish is the material that forms the exposed interior surface of walls, ceilings and floor. There are many types of interior finish materials such as plaster, gypsum, wood and plastics. They serve several functions. Some functions of the interior material are acoustical and insulational, as well as protective against wear and abrasion.

Interior finish is related to fire in four different ways. It can affect the rate of fire build-up to flashover conditions, contribute to fire extension by flame spread, increase the heat release by adding fuel and produce smoke and toxic gases. Materials that exhibit high rates of flame spread, contribute fuel to a fire or produce hazardous quantities of smoke and toxic gases would be undesirable.

Smoke movement

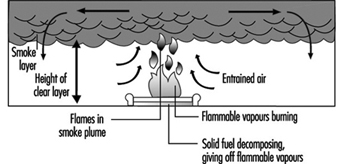

In building fires, smoke often moves to locations remote from the fire space. Stairwells and elevator shafts can become smoke-logged, thereby blocking evacuation and inhibiting fire-fighting. Today, smoke is recognized as the major killer in fire situations (see figure 1).

Figure 1. The production of smoke from a fire.

The driving forces of smoke movement include naturally occurring stack effect, buoyancy of combustion gases, the wind effect, fan-powered ventilation systems and the elevator piston effect.

When it is cold outside, there is an upward movement of air within building shafts. Air in the building has a buoyant force because it is warmer and therefore less dense than outside air. The buoyant force causes air to rise within building shafts. This phenomenon is known as the stack effect. The pressure difference from the shaft to the outside, which causes smoke movement, is illustrated below:

where

![]() = the pressure difference from the shaft to the outside

= the pressure difference from the shaft to the outside

g = acceleration of gravity

![]() = absolute atmospheric pressure

= absolute atmospheric pressure

R = gas constant of air

![]() = absolute temperature of outside air

= absolute temperature of outside air

![]() = absolute temperature of air inside the shaft

= absolute temperature of air inside the shaft

z = elevation

High-temperature smoke from a fire has a buoyancy force due to its reduced density. The equation for buoyancy of combustion gases is similar to the equation for the stack effect.

In addition to buoyancy, the energy released by a fire can cause smoke movement due to expansion. Air will flow into the fire compartment, and hot smoke will be distributed in the compartment. Neglecting the added mass of the fuel, the ratio of volumetric flows can simply be expressed as a ratio of absolute temperature.

Wind has a pronounced effect on smoke movement. The elevator piston effect should not be neglected. When an elevator car moves in a shaft, transient pressures are produced.

Heating, ventilating and air conditioning (HVAC) systems transport smoke during building fires. When a fire starts in an unoccupied portion of a building, the HVAC system can transport smoke to another occupied space. The HVAC system should be designed so that either the fans are shut down or the system transfers into a special smoke control mode operation.

Smoke movement can be managed by use of one or more of the following mechanisms: compartmentation, dilution, air flow, pressurization or buoyancy.

Evacuation of Occupants

Egress design

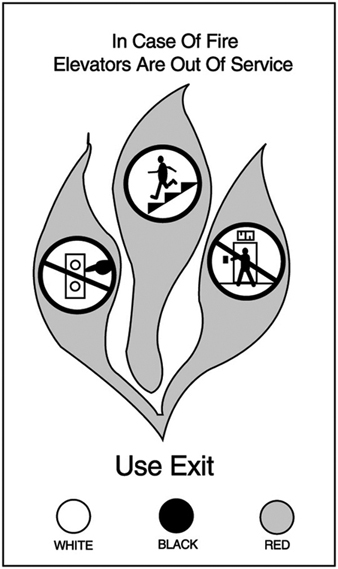

Egress design should be based upon an evaluation of a building’s total fire protection system (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Principles of exit safety.

People evacuating from a burning building are influenced by a number of impressions during their escape. The occupants have to make several decisions during the escape in order to make the right choices in each situation. These reactions can differ widely, depending upon the physical and mental capabilities and conditions of building occupants.

The building will also influence the decisions made by the occupants by its escape routes, guidance signs and other installed safety systems. The spread of fire and smoke will have the strongest impact on how the occupants make their decisions. The smoke will limit the visibility in the building and create a non-tenable environment to the evacuating persons. Radiation from fire and flames creates large spaces that cannot be used for evacuation, which increases the risk.

In designing means of egress one first needs a familiarity with the reaction of people in fire emergencies. Patterns of movement of people must be understood.

The three stages of evacuation time are notification time, reaction time and time to evacuate. The notification time is related to whether there is a fire alarm system in the building or if the occupant is able to understand the situation or how the building is divided into compartments. The reaction time depends on the occupant’s ability to make decisions, the properties of the fire (such as the amount of heat and smoke) and how the building’s egress system is planned. Finally, the time to evacuate depends on where in the building crowds are formed and how people move in various situations.

In specific buildings with mobile occupants, for example, studies have shown certain reproducible flow characteristics from persons exiting the buildings. These predictable flow characteristics have fostered computer simulations and modelling to aid the egress design process.

The evacuation travel distances are related to the fire hazard of the contents. The higher the hazard, the shorter the travel distance to an exit.

A safe exit from a building requires a safe path of escape from the fire environment. Hence, there must be a number of properly designed means of egress of adequate capacity. There should be at least one alternative means of egress considering that fire, smoke and the characteristics of occupants and so on may prevent use of one means of egress. The means of egress must be protected against fire, heat and smoke during the egress time. Thus, it is necessary to have building codes that consider the passive protection, according to evacuation and of course to fire protection. A building must manage the critical situations, which are given in the codes concerning evacuation. For example, in the Swedish Building Codes, the smoke layer must not reach below

1.6 + 0.1H (H is the total compartment height), maximum radiation 10 kW/m2 of short duration, and the temperature in the breathing air must not exceed 80 °C.

An effective evacuation can take place if a fire is discovered early and the occupants are alerted promptly with a detection and alarm system. A proper mark of the means of egress surely facilitates the evacuation. There is also a need for organization and drill of evacuation procedures.

Human behaviour during fires

How one reacts during a fire is related to the role assumed, previous experience, education and personality; the perceived threat of the fire situation; the physical characteristics and means of egress available within the structure; and the actions of others who are sharing the experience. Detailed interviews and studies over 30 years have established that instances of non-adaptive, or panic, behaviour are rare events that occur under specific conditions. Most behaviour in fires is determined by information analysis, resulting in cooperative and altruistic actions.

Human behaviour is found to pass through a number of identified stages, with the possibility of various routes from one stage to the next. In summary, the fire is seen as having three general stages:

- The individual receives initial cues and investigates or misinterprets these initial cues.

- Once the fire is apparent, the individual will try to obtain further information, contact others or leave.

- The individual will thereafter deal with the fire, interact with others or escape.

Pre-fire activity is an important factor. If a person is engaged in a well-known activity, for example eating a meal in a restaurant, the implications for subsequent behaviour are considerable.

Cue reception may be a function of pre-fire activity. There is a tendency for gender differences, with females more likely to be recipient of noises and odours, though the effect is only slight. There are role differences in initial responses to the cue. In domestic fires, if the female receives the cue and investigates, the male, when told, is likely to “have a look” and delay further actions. In larger establishments, the cue may be an alarm warning. Information may come from others and has been found to be inadequate for effective behaviour.

Individuals may or may not have realized that there is a fire. An understanding of their behaviour must take account of whether they have defined their situation correctly.

When the fire has been defined, the “prepare” stage occurs. The particular type of occupancy is likely to have a great influence on exactly how this stage develops. The “prepare” stage includes in chronological order “instruct”, “explore” and “withdraw”.

The “act” stage, which is the final stage, depends upon role, occupancy, and earlier behaviour and experience. It may be possible for early evacuation or effective fire-fighting to occur.

Building transportation systems

Building transportation systems must be considered during the design stage and should be integrated with the whole building’s fire protection system. The hazards associated with these systems must be included in any pre-fire planning and fire protection survey.

Building transportation systems, such as elevators and escalators, make high-rise buildings feasible. Elevator shafts can contribute to the spread of smoke and fire. On the other hand, an elevator is a necessary tool for fire-fighting operations in high-rise buildings.

Transportation systems may contribute to dangerous and complicated fire safety problems because an enclosed elevator shaft acts as a chimney or flue because of the stack effect of hot smoke and gases from fire. This generally results in the movement of smoke and combustion products from lower to upper levels of the building.

High-rise buildings present new and different problems to fire-suppression forces, including the use of elevators during emergencies. Elevators are unsafe in a fire for several reasons:

- Persons may push a corridor button and have to wait for an elevator that may never respond, losing valuable escape time.

- Elevators do not prioritize car and corridor calls, and one of the calls may be at the fire floor.

- Elevators cannot start until the lift and shaft doors are closed, and panic could lead to overcrowding of an elevator and the blockage of the doors, which would thus prevent closing.

- The power can fail during a fire at any time, thus leading to entrapment. (See figure 3)

Figure 3. An example of a pictographic warning message for elevator use.

Fire drills and occupant training

A proper mark of the means of egress facilitates the evacuation, but it does not ensure life safety during fire. Exit drills are necessary to make an orderly escape. They are specially required in schools, board and care facilities and industries with high hazard. Employee drills are required, for example, in hotel and large business occupancies. Exit drills should be conducted to avoid confusion and ensure the evacuation of all occupants.

All employees should be assigned to check for availability, to count occupants when they are outside the fire area, to search for stragglers and to control re-entry. They should also recognize the evacuation signal and know the exit route they are to follow. Primary and alternative routes should be established, and all employees should be trained to use either route. After each exit drill, a meeting of responsible managers should be held to evaluate the success of the drill and to solve any kind of problem that could have occurred.

Active Fire Protection Measures

Life Safety and Property Protection

As the primary importance of any fire protection measure is to provide an acceptable degree of life safety to inhabitants of a structure, in most countries legal requirements applying to fire protection are based on life safety concerns. Property protection features are intended to limit physical damage. In many cases these objectives are complementary. Where concern exists with the loss of property, its function or contents, an owner may choose to implement measures beyond the required minimum necessary to address life safety concerns.

Fire Detection and Alarm Systems

A fire detection and alarm system provides a means to detect fire automatically and to warn building occupants of the threat of fire. It is the audible or visual alarm provided by a fire detection system that is the signal to begin the evacuation of the occupants from the premises. This is especially important in large or multi-storey buildings where occupants would be unaware that a fire was underway within the structure and where it would be unlikely or impractical for warning to be provided by another inhabitant.

Basic elements of a fire detection and alarm system

A fire detection and alarm system may include all or some of the following:

- a system control unit

- a primary or main electrical power supply

- a secondary (stand-by) power supply, usually supplied from batteries or an emergency generator

- alarm-initiating devices such as automatic fire detectors, manual pull stations and/or sprinkler system flow devices, connected to “initiating circuits” of the system control unit

- alarm-indicating devices, such as bells or lights, connected to “indicating circuits” of the system control unit

- ancillary controls such as ventilation shut-down functions, connected to output circuits of the system control unit

- remote alarm indication to an external response location, such as the fire department

- control circuits to activate a fire protection system or smoke control system.

Smoke Control Systems

To reduce the threat of smoke from entering exit paths during evacuation from a structure, smoke control systems can be used. Generally, mechanical ventilation systems are employed to supply fresh air to the exit path. This method is most often used to pressurize stairways or atrium buildings. This is a feature intended to enhance life safety.

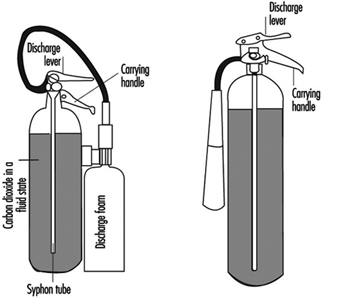

Portable Fire Extinguishers and Hose Reels

Portable fire extinguishers and water hose reels are often provided for use by building occupants to fight small fires (see figure 1). Building occupants should not be encouraged to use a portable fire extinguisher or hose reel unless they have been trained in their use. In all cases, operators should be very cautious to avoid placing themselves in a position where safe egress is blocked. For any fire, no matter how small, the first action should always be to notify other building occupants of the threat of fire and summon assistance from the professional fire service.

Figure 1. Portable fire extinguishers.

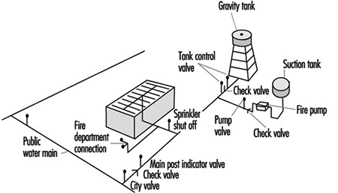

Water Sprinkler Systems

Water sprinkler systems consist of a water supply, distribution valves and piping connected to automatic sprinkler heads (see figure 2). While current sprinkler systems are primarily intended to control the spread of fire, many systems have accomplished complete extinguishment.

Figure 2. A typical sprinkler installation showing all common water supplies, outdoor hydrants and underground piping.

A common misconception is that all automatic sprinkler heads open in the event of a fire. In fact, each sprinkler head is designed to open only when sufficient heat is present to indicate a fire. Water then flows only from the sprinkler head(s) that have opened as the result of fire in their immediate vicinity. This design feature provides efficient use of water for fire-fighting and limits water damage.

Water supply

Water for an automatic sprinkler system must be available in sufficient quantity and at sufficient volume and pressure at all times to ensure reliable operation in the event of fire. Where a municipal water supply cannot meet this requirement, a reservoir or pump arrangement must be provided to provide a secure water supply.

Control valves

Control valves should be maintained in the open position at all times. Often, supervision of the control valves can be accomplished by the automatic fire alarm system by provision of valve tamper switches that will initiate a trouble or supervisory signal at the fire alarm control panel to indicate a closed valve. If this type of monitoring cannot be provided, the valves should be locked in the open position.

Piping

Water flows through a piping network, ordinarily suspended from the ceiling, with the sprinkler heads suspended at intervals along the pipes. Piping used in sprinkler systems should be of a type that can withstand a working pressure of not less than 1,200 kPa. For exposed piping systems, fittings should be of the screwed, flanged, mechanical joint or brazed type.

Sprinkler heads

A sprinkler head consists of an orifice, normally held closed by a temperature-sensitive releasing element, and a spray deflector. The water discharge pattern and spacing requirements for individual sprinkler heads are used by sprinkler designers to ensure complete coverage of the protected risk.

Special Extinguishing Systems

Special extinguishing systems are used in cases where water sprinklers would not provide adequate protection or where the risk of damage from water would be unacceptable. In many cases where water damage is of concern, special extinguishing systems may be used in conjunction with water sprinkler systems, with the special extinguishing system designed to react at an early stage of fire development.

Water and water-additive special extinguishing systems

Water spray systems

Water spray systems increase the effectiveness of water by producing smaller water droplets, and thus a greater surface area of water is exposed to the fire, with a relative increase in heat absorption capability. This type of system is often chosen as a means of keeping large pressure vessels, such as butane spheres, cool when there is a risk of an exposure fire originating in an adjacent area. The system is similar to a sprinkler system; however, all heads are open, and a separate detection system or manual action is used to open control valves. This allows water to flow through the piping network to all spray devices that serve as outlets from the piping system.

Foam systems

In a foam system, a liquid concentrate is injected into the water supply before the control valve. Foam concentrate and air are mixed, either through the mechanical action of discharge or by aspirating air into the discharge device. The air entrained in the foam solution creates an expanded foam. As expanded foam is less dense than most hydrocarbons, the expanded foam forms a blanket on top of the flammable liquid. This foam blanket reduces fuel vapour propagation. Water, which represents as much as 97% of the foam solution, provides a cooling effect to further reduce vapour propagation and to cool hot objects that could serve as a source of re-ignition.

Gaseous extinguishing systems

Carbon dioxide systems

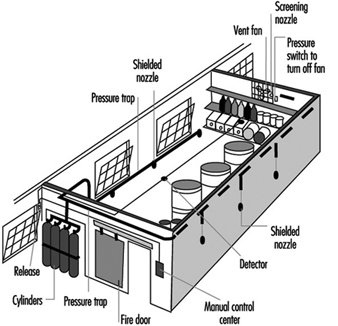

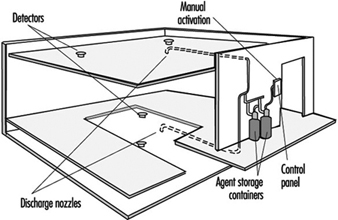

Carbon dioxide systems consist of a supply of carbon dioxide, stored as liquified compressed gas in pressure vessels (see figures 3 and 4). The carbon dioxide is held in the pressure vessel by means of an automatic valve that is opened upon fire by means of a separate detection system or by manual operation. Once released, the carbon dioxide is delivered to the fire by means of a piping and discharge nozzle arrangement. Carbon dioxide extinguishes fire by displacing the oxygen available to the fire. Carbon dioxide systems can be designed for use in open areas such as printing presses or enclosed volumes such as ship machinery spaces. Carbon dioxide, at fire-extinguishing concentrations, is toxic to people, and special measures must be employed to ensure that persons in the protected area are evacuated before discharge occurs. Pre-discharge alarms and other safety measures must be carefully incorporated into the design of the system to ensure adequate safety for people working in the protected area. Carbon dioxide is considered to be a clean extinguishant because it does not cause collateral damage and is electrically non-conductive.

Figure 3. Diagram of a high-pressure carbon dioxide system for total flooding.

Figure 4. A total flooding system installed in a room with a raised floor.

Inert gas systems

Inert gas systems generally use a mixture of nitrogen and argon as an extinguishing medium. In some cases, a small percentage of carbon dioxide is also provided in the gas mixture. The inert gas mixtures extinguish fires by reducing oxygen concentration within a protected volume. They are suitable for use in enclosed spaces only. The unique feature offered by inert gas mixtures is that they reduce the oxygen to a low enough concentration to extinguish many types of fires; however, oxygen levels are not sufficiently lowered to pose an immediate threat to occupants of the protected space. The inert gases are compressed and stored in pressure vessels. System operation is similar to a carbon dioxide system. As the inert gases cannot be liquefied by compression, the number of storage vessels required for protection of a given enclosed protected volume is greater than that for carbon dioxide.

Halon systems

Halons 1301, 1211 and 2402 have been identified as ozone-depleting substances. Production of these extinguishing agents ceased in 1994, as required by the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement to protect the earth’s ozone layer. Halon 1301 was most often used in fixed fire protection systems. Halon 1301 was stored as liquefied, compressed gas in pressure vessels in a similar arrangement to that used for carbon dioxide. The advantage offered by halon 1301 was that storage pressures were lower and that very low concentrations provided effective extinguishing capability. Halon 1301 systems were used successfully for totally enclosed hazards where the extinguishing concentration achieved could be maintained for a sufficient time for extinguishment to occur. For most risks, concentrations used did not pose an immediate threat to occupants. Halon 1301 is still used for several important applications where acceptable alternatives have yet to be developed. Examples include use on-board commercial and military aircraft and for some special cases where inerting concentrations are required to prevent explosions in areas where occupants could be present. The halon in existing halon systems that are no longer required should be made available for use by others with critical applications. This will militate against the need to produce more of these environmentally sensitive extinguishers and help protect the ozone layer.

Halocarbon systems

Halocarbon agents were developed as the result of the environmental concerns associated with halons. These agents differ widely in toxicity, environmental impact, storage weight and volume requirements, cost and availability of approved system hardware. They all can be stored as liquefied compressed gases in pressure vessels. System configuration is similar to a carbon dioxide system.

Design, Installation and Maintenance of Active Fire Protection Systems

Only those skilled in this work are competent to design, install and maintain this equipment. It may be necessary for many of those charged with purchasing, installing, inspecting, testing, approving and maintaining this equipment to consult with an experienced and competent fire protection specialist to discharge their duties effectively.

Further Information

This section of the Encyclopaedia presents a very brief and limited overview of the available choice of active fire protection systems. Readers may often obtain more information by contacting a national fire protection association, their insurer or the fire prevention department of their local fire service.

Organizing for Fire Protection

Private Emergency Organization

Profit is the main objective of any industry. To achieve this objective, an efficient and alert management and continuity of production are essential. Any interruption in production, for any reason, will adversely affect profits. If the interruption is the result of a fire or explosion, it may be long and may cripple the industry.

Very often, a plea is taken that the property is insured and loss due to fire, if any, will be indemnified by the insurance company. It must be appreciated that insurance is only a device to spread the effect of the destruction brought by fire or explosion on as many people as possible. It cannot make good the national loss. Besides, insurance is no guarantee of continuity of production and elimination or minimization of consequential losses.

What is indicated, therefore, is that the management must gather complete information on the fire and explosion hazard, evaluate the loss potential and implement suitable measures to control the hazard, with a view to eliminating or minimizing the incidence of fire and explosion. This involves the setting up of a private emergency organization.

Emergency Planning

Such an organization must, as far as possible, be considered from the planning stage itself, and implemented progressively from the time of selection of site until production has started, and then continued thereafter.

Success of any emergency organization depends to a large extent on the overall participation of all workers and various echelons of the management. This fact must be borne in mind while planning the emergency organization.

The various aspects of emergency planning are mentioned below. For more details, a reference may be made to the US National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Fire Protection Handbook or any other standard work on the subject (Cote 1991).

Stage 1

Initiate the emergency plan by doing the following:

- Identify and evaluate fire and explosion hazards associated with the transportation, handling and storage of each raw material, intermediate and finished products and each industrial process, as well as work out detailed preventive measures to counteract the hazards with a view to eliminating or minimizing them.

- Work out the requirements of fire protection installations and equipment, and determine the stages at which each is to be provided.

- Prepare specifications for the fire protection installation and equipment.

Stage 2

Determine the following:

- availability of adequate water supply for fire protection in addition to the requirements for processing and domestic use

- susceptibility of site and natural hazards, such as floods, earthquakes, heavy rains, etc.

- environments, i.e., the nature and extent of surrounding property and the exposure hazard involved in the event of a fire or explosion

- existence of private (works) or public fire brigade(s), the distance at which such fire brigade(s) is (are) located and the suitability of the appliances available with them for the risk to be protected and whether they can be called upon to assist in an emergency

- response from the assisting fire brigade(s) with particular reference to impediments, such as railway crossings, ferries, inadequate strength and (or) width of bridges in relation to the fire appliances, difficult traffic, etc.

- socio-political environment , i.e., incidence of crime, and political activities leading to law-and-order problems.

Stage 3

Prepare the layout and building plans, and the specifications of construction material. Carry out the following tasks:

- Limit the floor area of each shop, workplace, etc. by providing fire walls, fire doors, etc.

- Specify the use of fire-resistant materials for construction of building or structure.

- Ensure that steel columns and other structural members are not exposed.

- Ensure adequate separation between building, structures and plant.

- Plan installation of fire hydrants, sprinklers, etc. where necessary.

- Ensure the provision of adequate access roads in the layout plan to enable fire appliances to reach all parts of the premises and all sources of water for fire-fighting.

Stage 4

During construction, do the following:

- Acquaint the contractor and his or her employees with the fire risk management policies, and enforce compliance.

- Thoroughly test all fire protection installations and equipment before acceptance.

Stage 5

If the size of the industry, its hazards or its out-of-the-way location is such that a full-time fire brigade must be available on the premises, then organize, equip and train the required full-time personnel. Also appoint a full-time fire officer.

Stage 6

To ensure full participation of all employees, do the following:

- Train all personnel in the observance of precautionary measures in their day-to-day work and the action required of them upon an outbreak of fire or explosion. The training must include operation of fire-fighting equipment.

- Ensure strict observance of fire precautions by all concerned personnel through periodic reviews.

- Ensure regular inspection and maintenance of all fire protection systems and equipment. All defects must be rectified promptly.

Managing the emergency

To avoid confusion at the time of an actual emergency, it is essential that everyone in the organization knows the precise part that he (she) and others are expected to play during the emergency. A well-thought-out emergency plan must be prepared and promulgated for this purpose, and all concerned personnel must be made fully familiar with it. The plan must clearly and unambiguously lay down the responsibilities of all concerned and also specify a chain of command. As a minimum, the emergency plan should include the following:

1. name of the industry

2. address of the premises, with telephone number and a site plan

3. purpose and objective of the emergency plan and effective date of its coming in force

4. area covered, including a site plan

5. emergency organization, indicating chain of command from the work manager on downwards

6. fire protection systems, mobile appliances and portable equipment, with details

7. details of assistance availability

8. fire alarm and communication facilities

9. action to be taken in an emergency. Include separately and unambiguously the action to be taken by:

- the person discovering the fire

- the private fire brigade on the premises

- head of the section involved in the emergency

- heads of other sections not actually involved in theemergency

- the security organization

- the fire officer, if any

- the works manager

- others

10. chain of command at the scene of incident. Consider all possible situations, and indicate clearly who is to assume command in each case, including the circumstances under which another organization is to be called in to assist.

11. action after a fire. Indicate responsibility for:

- recommissioning or replenishing of all fire protectionsystems, equipment and water sources

- investigating the cause of fire or explosion

- preparation and submission of reports

- initiating remedial measures to prevent re-occurrence of similar emergency.

When a mutual assistance plan is in operation, copies of emergency plan must be supplied to all participating units in return for similar plans of their respective premises.

Evacuation Protocols

A situation necessitating the execution of the emergency plan may develop as a result of either an explosion or a fire.

Explosion may or may not be followed by fire, but in almost all cases, it produces a shattering effect, which may injure or kill personnel present in the vicinity and/or cause physical damage to property, depending upon the circumstances of each case. It may also cause shock and confusion and may necessitate the immediate shut-down of the manufacturing processes or a portion thereof, along with the sudden movement of a large number of people. If the situation is not controlled and guided in an orderly manner immediately, it may lead to panic and further loss of life and property.

Smoke given out by the burning material in a fire may involve other parts of the property and/or trap persons, necessitating an intensive, large-scale rescue operation/evacuation. In certain cases, large-scale evacuation may have to be undertaken when people are likely to get trapped or affected by fire.

In all cases in which large-scale sudden movement of personnel is involved, traffic problems are also created—particularly if public roads, streets or areas have to be used for this movement. If such problems are not anticipated and suitable action is not preplanned, traffic bottlenecks result, which hamper and retard fire extinguishment and rescue efforts.

Evacuation of a large number of persons—particularly from high-rise buildings—may also present problems. For successful evacuation, it is not only necessary that adequate and suitable means of escape are available, but also that the evacuation be effected speedily. Special attention should be given to the evacuation needs of disabled individuals.

Detailed evacuation procedures must, therefore, be included in the emergency plan. These must be frequently tested in the conduct of fire and evacuation drills, which may also involve traffic problems. All participating and concerned organizations and agencies must also be involved in these drills, at least periodically. After each exercise, a debriefing session must be held, during which all mistakes are pointed out and explained. Action must also be taken to prevent repetition of the same mistakes in future exercises and actual incidents by removing all difficulties and reviewing the emergency plan as necessary.

Proper records must be maintained of all exercises and evacuation drills.

Emergency Medical Services

Casualties in a fire or explosion must receive immediate medical aid or be moved speedily to a hospital after being given first aid.

It is essential that management provide one or more first-aid post(s) and, where necessary because of the size and hazardous nature of the industry, one or more mobile paramedical appliances. All first-aid posts and paramedical appliances must be staffed at all times by fully trained paramedics.

Depending upon the size of the industry and the number of workers, one or more ambulance(s) must also be provided and staffed on the premises for removal of casualties to hospitals. In addition, arrangement must be made to ensure that additional ambulance facilities are available at short notice when needed.

Where the size of the industry or workplace so demands, a full-time medical officer should also be made available at all times for any emergency situation.

Prior arrangements must be made with a designated hospital or hospitals at which priority is given to casualties who are removed after a fire or explosion. Such hospitals must be listed in the emergency plan along with their telephone numbers, and the emergency plan must have suitable provisions to ensure that a responsible person shall alert them to receive casualties as soon as an emergency arises.

Facility Restoration

It is important that all fire protection and emergency facilities are restored to a “ready” mode soon after the emergency is over. For this purpose, responsibility must be assigned to a person or section of the industry, and this must be included in the emergency plan. A system of checks to ensure that this is being done must also be introduced.

Public Fire Department Relations

It is not practicable for any management to foresee and provide for all possible contingencies. It is also not economically feasible to do so. In spite of adopting the most up-to-date method of fire risk management, there are always occasions when the fire protection facilities provided on the premises fall short of actual needs. For such occasions, it is desirable to preplan a mutual assistance programme with the public fire department. Good liaison with that department is necessary so that the management knows what assistance that unit can provide during an emergency on its premises. Also, the public fire department must become familiar with the risk and what it could expect during an emergency. Frequent interaction with the public fire department is necessary for this purpose.

Handling of Hazardous Materials

Hazards of the materials used in industry may not be known to fire-fighters during a spill situation, and accidental discharge and improper use or storage of hazardous materials can lead to dangerous situations that can seriously imperil their health or lead to a serious fire or explosion. It is not possible to remember the hazards of all materials. Means of ready identification of hazards have, therefore, been developed whereby the various substances are identified by distinct labels or markings.

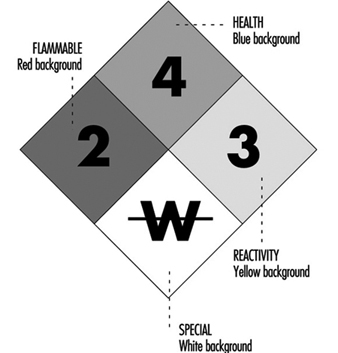

Hazardous materials identification

Each country follows its own rules concerning the labelling of hazardous materials for the purpose of storage, handling and transportation, and various departments may be involved. While compliance with local regulations is essential, it is desirable that an internationally recognized system of identification of hazardous materials be evolved for universal application. In the United States, the NFPA has developed a system for this purpose. In this system, distinct labels are conspicuously attached or affixed to containers of hazardous materials. These labels indicate the nature and degree of hazards in respect of health, flammability and the reactive nature of the material. In addition, special possible hazards to fire-fighters can also be indicated on these labels. For an explanation of the degree of hazard, refer to NFPA 704, Standard System for the Identification of the Fire Hazards of Materials (1990a). In this system, the hazards are categorized as health hazards, flammability hazards, and reactivity (instability) hazards.

Health hazards

These include all possibilities of a material causing personal injury from contact with or absorption into the human body. A health hazard may arise out of the inherent properties of the material or from the toxic products of combustion or decomposition of the material. The degree of hazard is assigned on the basis of the greater hazard that may result under fire or other emergency conditions. It indicates to fire-fighters whether they can work safely only with special protective clothing or with suitable respiratory protective equipment or with ordinary clothing.

Degree of health hazard is measured on a scale of 4 to 0, with 4 indicating the most severe hazard and 0 indicating low hazard or no hazard.

Flammability hazards

These indicate the susceptibility of the material to burning. It is recognized that materials behave differently in respect of this property under varying circumstances (e.g., materials that may burn under one set of conditions may not burn if the conditions are altered). The form and inherent properties of the materials influence the degree of hazard, which is assigned on the same basis as for the health hazard.

Reactivity (instability) hazards

Materials capable of releasing energy by itself, (i.e., by self-reaction or polymerization) and substances that can undergo violent eruption or explosive reactions on coming in contact with water, other extinguishing agents or certain other materials are said to possess a reactivity hazard.

The violence of reaction may increase when heat or pressure is applied or when the substance comes in contact with certain other materials to form a fuel-oxidizer combination, or when it comes in contact with incompatible substances, sensitizing contaminants or catalysts.

The degree of reactivity hazard is determined and expressed in terms of the ease, rate and quantity of energy release. Additional information, such as radioactivity hazard or prohibition of water or other extinguishing medium for fire-fighting, can also be given on the same level.

The label warning of a hazardous material is a diagonally placed square with four smaller squares (see figure 1).

Figure 1. The NFPA 704 diamond.

The top square indicates the health hazard, the one on the left indicates the flammability hazard, the one on the right indicates the reactivity hazard, and the bottom square indicates other special hazards, such as radioactivity or unusual reactivity with water.

To supplement the above mentioned arrangement, a colour code may also be used. The colour is used as background or the numeral indicating the hazard may be in coded colour. The codes are health hazard (blue), flammability hazard (red), reactivity hazard (yellow) and special hazard (white background).

Managing hazardous materials response

Depending on the nature of the hazardous material in the industry, it is necessary to provide protective equipment and special fire-extinguishing agents, including the protective equipment required to dispense the special extinguishing agents.

All workers must be trained in the precautions they must take and the procedures they must adopt to deal with each incident in the handling of the various types of hazardous materials. They must also know the meaning of the various identification signs.

All fire-fighters and other workers must be trained in the correct use of any protective clothing, protective respiratory equipment and special fire-fighting techniques. All concerned personnel must be kept alert and prepared to tackle any situation through frequent drills and exercises, of which proper records should be kept.

To deal with serious medical hazards and the effects of these hazards on fire-fighters, a competent medical officer should be available to take immediate precautions when any individual is exposed to unavoidable dangerous contamination. All affected persons must receive immediate medical attention.

Proper arrangements must also be made to set up a decontamination centre on the premises when necessary, and correct decontamination procedures must be laid down and followed.

Waste control

Considerable waste is generated by industry or because of accidents during handling, transportation and storage of goods. Such waste may be flammable, toxic, corrosive, pyrophoric, chemically reactive or radioactive, depending upon the industry in which it is generated or the nature of goods involved. In most cases unless proper care is taken in safe disposal of such waste, it may endanger animal and human life, pollute the environment or cause fire and explosions that may endanger property. A thorough knowledge of the physical and chemical properties of the waste materials and of the merits or limitations of the various methods of their disposal is, therefore, necessary to ensure economy and safety.

Properties of industrial waste are briefly summarized below:

- Most industrial waste is hazardous and can have unexpected significance during and after disposal. The nature and behavioural characteristics of all waste must therefore be carefully examined for their short- and long-term impact and the method of disposal determined accordingly.

- Mixing of two seemingly innocuous discarded substances may create an unexpected hazard because of their chemical or physical interaction.

- Where flammable liquids are involved, their hazards can be assessed by taking into consideration their respective flash points, ignition temperature, flammability limits and the ignition energy required to initiate combustion. In the case of solids, particle size is an additional factor that must be considered.

- Most flammable vapours are heavier than air. Such vapours and heavier-than-air flammable gases that may be accidentally released during collection or disposal or during handling and transportation can travel considerable distances with the wind or towards a lower gradient. On coming in contact with a source of ignition, they flash back to source. Major spills of flammable liquids are particularly hazardous in this respect and may require evacuation to save lives.

- Pyrophoric materials, such as aluminium alkyls, ignite spontaneously when exposed to air. Special care must therefore be taken in handling, transportation, storage and disposal of such materials, preferably carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere.

- Certain materials, such as potassium, sodium and aluminium alkyls, react violently with water or moisture and burn fiercely. Bronze powder generates considerable heat in the presence of moisture.

- The presence of potent oxidants with organic materials can cause rapid combustion or even an explosion. Rags and other materials soaked with vegetable oils or terpenes present a risk of spontaneous combustion due to the oxidation of oils and subsequent build-up of heat to the ignition temperature.

- Several substances are corrosive and may cause severe damage or burns to skin or other living tissues, or may corrode construction materials, especially metals, thereby weakening the structure in which such materials may have been used.

- Some substances are toxic and can poison humans or animals by contact with skin, inhalation or contamination of food or water. Their ability to do so may be short lived or may extend over a long period. Such substances, if disposed of by dumping or burning, can contaminate water sources or come into contact with animals or workers.

- Toxic substances that are spilled during industrial processing, transportation (including accidents), handling or storage, and toxic gases that are released into the atmosphere can affect emergency personnel and others, including the public. The hazard is all the more severe if the spilled substance(s) is vaporized at ambient temperature, because the vapours can be carried over long distances due to wind drift or run-off.

- Certain substances may emit a strong, pungent or unpleasant odour, either by themselves or when they are burnt in the open. In either case, such substances are a public nuisance, even though they may not be toxic, and they must be disposed of by proper incineration, unless it is possible to collect and recycle them. Just as odorous substances are not necessarily toxic, odourless substances and some substances with a pleasant odour may produce harmful physiological effects.

- Certain substances, such as explosives, fireworks, organic peroxides and some other chemicals, are sensitive to heat or shock and may explode with devastating effect if not handled carefully or mixed with other substances. Such substances must, therefore, be carefully segregated and destroyed under proper supervision.

- Waste materials that are contaminated with radioactivity can be as hazardous as the radioactive materials themselves. Their disposal requires specialized knowledge. Proper guidance for disposal of such waste may be obtained from a country’s nuclear energy organization.

Some of the methods that may be employed to dispose of industrial and emergency waste are biodegradation, burial, incineration, landfill, mulching, open burning, pyrolysis and disposal through a contractor. These are briefly explained below.

Biodegradation

Many chemicals are completely destroyed within six to 24 months when they are mixed with the top 15 cm of soil. This phenomenon is known as biodegradation and is due to the action of soil bacteria. Not all substances, however, behave in this way.

Burial

Waste, particularly chemical waste, is often disposed of by burial. This is a dangerous practice in so far as active chemicals are concerned, because, in time, the buried substance may get exposed or leached by rain into water resources. The exposed substance or the contaminated material can have adverse physiological effects when it comes in contact with water that is drunk by humans or animals. Cases are on record in which water was contaminated 40 years after burial of certain harmful chemicals.

Incineration

This is one of the safest and most satisfactory methods of waste disposal if the waste is burned in a properly designed incinerator under controlled conditions. Care must be taken, however, to ensure that the substances contained in the waste are amenable to safe incineration without posing any operating problem or special hazard. Almost all industrial incinerators require the installation of air pollution control equipment, which must be carefully selected and installed after taking into consideration the composition of the stock effluent given out by the incinerator during the burning of industrial waste.

Care must be taken in the operation of the incinerator to ensure that its operative temperature does not rise excessively either because a large amount of volatiles is fed or because of the nature of the waste burned. Structural failure can occur because of excessive temperature, or, over time, because of corrosion. The scrubber must also be periodically inspected for signs of corrosion which can occur because of contact with acids, and the scrubber system must be maintained regularly to ensure proper functioning.

Landfill

Low-lying land or a depression in land is often used as a dump for waste materials until it becomes level with the surrounding land. The waste is then levelled, covered with earth and rolled hard. The land is then used for buildings or other purposes.

For satisfactory landfill operation, the site must be selected with due regard to the proximity of pipelines, sewer lines, power lines, oil and gas wells, mines and other hazards. The waste must then be mixed with earth and evenly spread out in the depression or a wide trench. Each layer must be mechanically compacted before the next layer is added.

A 50 cm layer of earth is typically laid over the waste and compacted, leaving sufficient vents in the soil for the escape of gas that is produced by biological activity in the waste. Attention must also be paid to proper drainage of the landfill area.

Depending on the various constituents of waste material, it may at times ignite within the landfill. Each such area must, therefore, be properly fenced off and continued surveillance maintained until the chances of ignition appear to be remote. Arrangements must also be made for extinguishing any fire that may break out in the waste within the landfill.

Mulching

Some trials have been made for reusing polymers as mulch (loose material for protecting the roots of plants) by chopping the waste into small shreds or granules. When so used, it degrades very slowly. Its effect on the soil is, therefore, purely physical. This method has, however, not been used widely.

Open burning

Open burning of waste causes pollution of the atmosphere and is hazardous in as much as there is a chance of the fire getting out of control and spreading to the surrounding property or areas. Also, there is a chance of explosion from containers, and there is a possibility of harmful physiological effects of radioactive materials that may be contained in the waste. This method of disposal has been banned in some countries. It is not a desirable method and should be discouraged.

Pyrolysis

Recovery of certain compounds, by distillation of the products given out during pyrolysis (decomposition by heating) of polymers and organic substances, is possible, but not yet widely adopted.

Disposal through contractors

This is probably the most convenient method. It is important that only reliable contractors who are knowledgeable and experienced in the disposal of industrial waste and hazardous materials are selected for the job. Hazardous materials must be carefully segregated and disposed of separately.