Children categories

36. Barometric Pressure Increased (2)

36. Barometric Pressure Increased

Chapter Editor: T.J.R. Francis

Table of Contents

Working under Increased Barometric Pressure

Eric Kindwall

Dees F. Gorman

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Instructions for compressed-air workers

2. Decompression illness: Revised classification

37. Barometric Pressure Reduced (4)

37. Barometric Pressure Reduced

Chapter Editor: Walter Dümmer

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

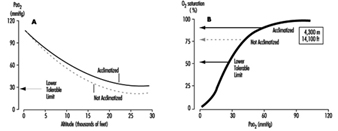

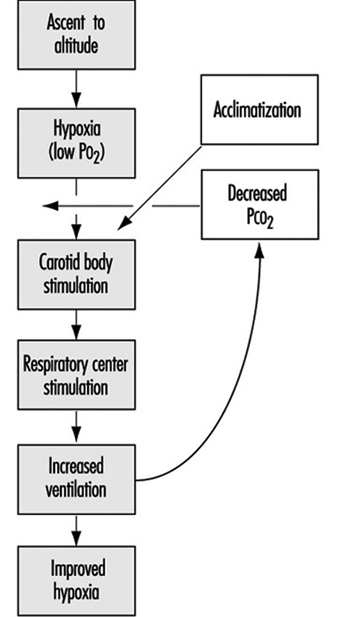

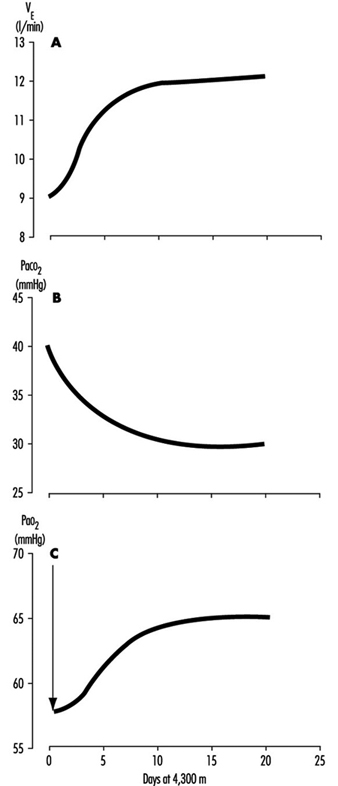

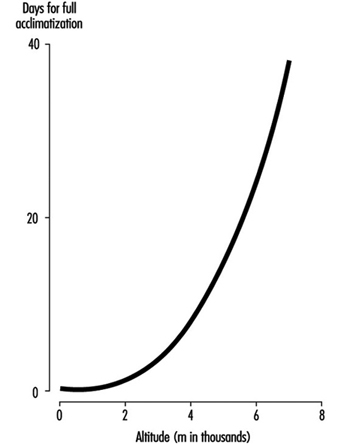

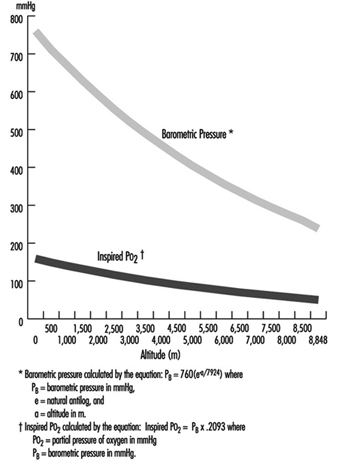

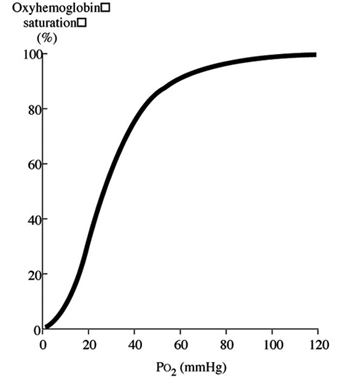

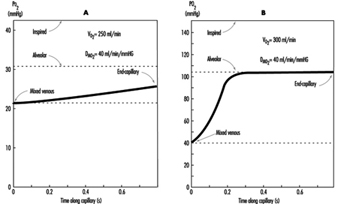

Ventilatory Acclimatization to High Altitude

John T. Reeves and John V. Weil

Physiological Effects of Reduced Barometric Pressure

Kenneth I. Berger and William N. Rom

Health Considerations for Managing Work at High Altitudes

John B. West

Prevention of Occupational Hazards at High Altitudes

Walter Dümmer

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

38. Biological Hazards (4)

38. Biological Hazards

Chapter Editor: Zuheir Ibrahim Fakhri

Table of Contents

Tables

Workplace Biohazards

Zuheir I. Fakhri

Aquatic Animals

D. Zannini

Terrestrial Venomous Animals

J.A. Rioux and B. Juminer

Clinical Features of Snakebite

David A. Warrell

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Occupational settings with biological agents

2. Viruses, bacteria, fungi & plants in the workplace

3. Animals as a source of occupational hazards

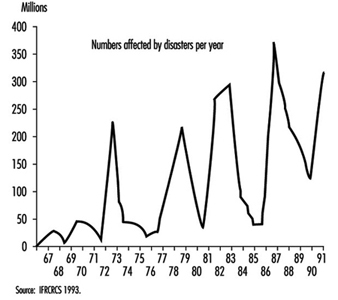

39. Disasters, Natural and Technological (12)

39. Disasters, Natural and Technological

Chapter Editor: Pier Alberto Bertazzi

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

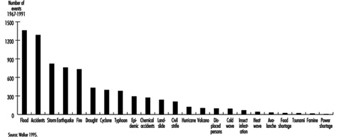

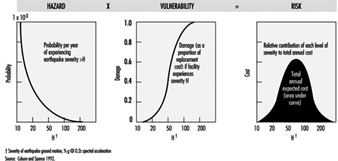

Disasters and Major Accidents

Pier Alberto Bertazzi

ILO Convention concerning the Prevention of Major Industrial Accidents, 1993 (No. 174)

Disaster Preparedness

Peter J. Baxter

Post-Disaster Activities

Benedetto Terracini and Ursula Ackermann-Liebrich

Weather-Related Problems

Jean French

Avalanches: Hazards and Protective Measures

Gustav Poinstingl

Transportation of Hazardous Material: Chemical and Radioactive

Donald M. Campbell

Radiation Accidents

Pierre Verger and Denis Winter

Case Study: What does dose mean?

Occupational Health and Safety Measures in Agricultural Areas Contaminated by Radionuclides: The Chernobyl Experience

Yuri Kundiev, Leonard Dobrovolsky and V.I. Chernyuk

Case Study: The Kader Toy Factory Fire

Casey Cavanaugh Grant

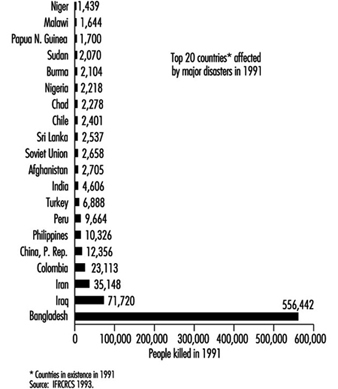

Impacts of Disasters: Lessons from a Medical Perspective

José Luis Zeballos

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Definitions of disaster types

2. 25-yr average # victims by type & region-natural trigger

3. 25-yr average # victims by type & region-non-natural trigger

4. 25-yr average # victims by type-natural trigger (1969-1993)

5. 25-yr average # victims by type-non-natural trigger (1969-1993)

6. Natural trigger from 1969 to 1993: Events over 25 years

7. Non-natural trigger from 1969 to 1993: Events over 25 years

8. Natural trigger: Number by global region & type in 1994

9. Non-natural trigger: Number by global region & type in 1994

10. Examples of industrial explosions

11. Examples of major fires

12. Examples of major toxic releases

13. Role of major hazard installations management in hazard control

14. Working methods for hazard assessment

15. EC Directive criteria for major hazard installations

16. Priority chemicals used in identifying major hazard installations

17. Weather-related occupational risks

18. Typical radionuclides, with their radioactive half-lives

19. Comparison of different nuclear accidents

20. Contamination in Ukraine, Byelorussia & Russia after Chernobyl

21. Contamination strontium-90 after the Khyshtym accident (Urals 1957)

22. Radioactive sources that involved the general public

23. Main accidents involving industrial irradiators

24. Oak Ridge (US) radiation accident registry (worldwide, 1944-88)

25. Pattern of occupational exposure to ionizing radiation worldwide

26. Deterministic effects: thresholds for selected organs

27. Patients with acute irradiation syndrome (AIS) after Chernobyl

28. Epidemiological cancer studies of high dose external irradiation

29. Thyroid cancers in children in Belarus, Ukraine & Russia, 1981-94

30. International scale of nuclear incidents

31. Generic protective measures for general population

32. Criteria for contamination zones

33. Major disasters in Latin America & the Caribbean, 1970-93

34. Losses due to six natural disasters

35. Hospitals & hospital beds damaged/ destroyed by 3 major disasters

36. Victims in 2 hospitals collapsed by the 1985 earthquake in Mexico

37. Hospital beds lost resulting from the March 1985 Chilean earthquake

38. Risk factors for earthquake damage to hospital infrastructure

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Click to return to top of page

40. Electricity (3)

40. Electricity

Chapter Editor: Dominique Folliot

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Electricity—Physiological Effects

Dominique Folliot

Static Electricity

Claude Menguy

Prevention And Standards

Renzo Comini

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Estimates of the rate of electrocution-1988

2. Basic relationships in electrostatics-Collection of equations

3. Electron affinities of selected polymers

4. Typical lower flammability limits

5. Specific charge associated with selected industrial operations

6. Examples of equipment sensitive to electrostatic discharges

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

41. Fire (6)

41. Fire

Chapter Editor: Casey C. Grant

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Basic Concepts

Dougal Drysdale

Sources of Fire Hazards

Tamás Bánky

Fire Prevention Measures

Peter F. Johnson

Passive Fire Protection Measures

Yngve Anderberg

Active Fire Protection Measures

Gary Taylor

Organizing for Fire Protection

S. Dheri

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Lower & upper flammability limits in air

2. Flashpoints & firepoints of liquid & solid fuels

3. Ignition sources

4. Comparison of concentrations of different gases required for inerting

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

42. Heat and Cold (12)

42. Heat and Cold

Chapter Editor: Jean-Jacques Vogt

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Physiological Responses to the Thermal Environment

W. Larry Kenney

Effects of Heat Stress and Work in the Heat

Bodil Nielsen

Heat Disorders

Tokuo Ogawa

Prevention of Heat Stress

Sarah A. Nunneley

The Physical Basis of Work in Heat

Jacques Malchaire

Assessment of Heat Stress and Heat Stress Indices

Kenneth C. Parsons

Case Study: Heat Indices: Formulae and Definitions

Heat Exchange through Clothing

Wouter A. Lotens

Cold Environments and Cold Work

Ingvar Holmér, Per-Ola Granberg and Goran Dahlstrom

Prevention of Cold Stress in Extreme Outdoor Conditions

Jacques Bittel and Gustave Savourey

Cold Indices and Standards

Ingvar Holmér

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Electrolyte concentration in blood plasma & sweat

2. Heat Stress Index & Allowable Exposure Times: calculations

3. Interpretation of Heat Stress Index values

4. Reference values for criteria of thermal stress & strain

5. Model using heart rate to assess heat stress

6. WBGT reference values

7. Working practices for hot environments

8. Calculation of the SWreq index & assessment method: equations

9. Description of terms used in ISO 7933 (1989b)

10. WBGT values for four work phases

11. Basic data for the analytical assessment using ISO 7933

12. Analytical assessment using ISO 7933

13. Air temperatures of various cold occupational environments

14. Duration of uncompensated cold stress & associated reactions

15. Indication of anticipated effects of mild & severe cold exposure

16. Body tissue temperature & human physical performance

17. Human responses to cooling: Indicative reactions to hypothermia

18. Health recommendations for personnel exposed to cold stress

19. Conditioning programmes for workers exposed to cold

20. Prevention & alleviation of cold stress: strategies

21. Strategies & measures related to specific factors & equipment

22. General adaptational mechanisms to cold

23. Number of days when water temperature is below 15 ºC

24. Air temperatures of various cold occupational environments

25. Schematic classification of cold work

26. Classification of levels of metabolic rate

27. Examples of basic insulation values of clothing

28. Classification of thermal resistance to cooling of handwear

29. Classification of contact thermal resistance of handwear

30. Wind Chill Index, temperature & freezing time of exposed flesh

31. Cooling power of wind on exposed flesh

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

43. Hours of Work (1)

43. Hours of Work

Chapter Editor: Peter Knauth

Table of Contents

Hours of Work

Peter Knauth

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Time intervals from beginning shiftwork until three illnesses

2. Shiftwork & incidence of cardiovascular disorders

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

44. Indoor Air Quality (8)

44. Indoor Air Quality

Chapter Editor: Xavier Guardino Solá

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Indoor Air Quality: Introduction

Xavier Guardino Solá

Nature and Sources of Indoor Chemical Contaminants

Derrick Crump

Radon

María José Berenguer

Tobacco Smoke

Dietrich Hoffmann and Ernst L. Wynder

Smoking Regulations

Xavier Guardino Solá

Measuring and Assessing Chemical Pollutants

M. Gracia Rosell Farrás

Biological Contamination

Brian Flannigan

Regulations, Recommendations, Guidelines and Standards

María José Berenguer

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Classification of indoor organic pollutants

2. Formaldehyde emission from a variety of materials

3. Ttl. volatile organic comp’ds concs, wall/floor coverings

4. Consumer prods & other sources of volatile organic comp’ds

5. Major types & concentrations in the urban United Kingdom

6. Field measurements of nitrogen oxides & carbon monoxide

7. Toxic & tumorigenic agents in cigarette sidestream smoke

8. Toxic & tumorigenic agents from tobacco smoke

9. Urinary cotinine in non-smokers

10. Methodology for taking samples

11. Detection methods for gases in indoor air

12. Methods used for the analysis of chemical pollutants

13. Lower detection limits for some gases

14. Types of fungus which can cause rhinitis and/or asthma

15. Micro-organisms and extrinsic allergic alveolitis

16. Micro-organisms in nonindustrial indoor air & dust

17. Standards of air quality established by the US EPA

18. WHO guidelines for non-cancer and non-odour annoyance

19. WHO guideline values based on sensory effects or annoyance

20. Reference values for radon of three organizations

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

45. Indoor Environmental Control (6)

45. Indoor Environmental Control

Chapter Editor: Juan Guasch Farrás

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Control of Indoor Environments: General Principles

A. Hernández Calleja

Indoor Air: Methods for Control and Cleaning

E. Adán Liébana and A. Hernández Calleja

Aims and Principles of General and Dilution Ventilation

Emilio Castejón

Ventilation Criteria for Nonindustrial Buildings

A. Hernández Calleja

Heating and Air-Conditioning Systems

F. Ramos Pérez and J. Guasch Farrás

Indoor Air: Ionization

E. Adán Liébana and J. Guasch Farrás

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Most common indoor pollutants & their sources

2. Basic requirements-dilution ventilation system

3. Control measures & their effects

4. Adjustments to working environment & effects

5. Effectiveness of filters (ASHRAE standard 52-76)

6. Reagents used as absorbents for contaminents

7. Levels of quality of indoor air

8. Contamination due to the occupants of a building

9. Degree of occupancy of different buildings

10. Contamination due to the building

11. Quality levels of outside air

12. Proposed norms for environmental factors

13. Temperatures of thermal comfort (based on Fanger)

14. Characteristics of ions

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

46. Lighting (3)

46. Lighting

Chapter Editor: Juan Guasch Farrás

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

Types of Lamps and Lighting

Richard Forster

Conditions Required for Visual

Fernando Ramos Pérez and Ana Hernández Calleja

General Lighting Conditions

N. Alan Smith

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Improved output & wattage of some 1,500 mm fluorescent tube lamps

2. Typical lamp efficacies

3. International Lamp Coding System (ILCOS) for some lamp types

4. Common colours & shapes of incandescent lamps & ILCOS codes

5. Types of high-pressure sodium lamp

6. Colour contrasts

7. Reflection factors of different colours & materials

8. Recommended levels of maintained illuminance for locations/tasks

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

47. Noise (5)

47. Noise

Chapter Editor: Alice H. Suter

Table of Contents

Figures and Tables

The Nature and Effects of Noise

Alice H. Suter

Noise Measurement and Exposure Evaluation

Eduard I. Denisov and German A. Suvorov

Engineering Noise Control

Dennis P. Driscoll

Hearing Conservation Programmes

Larry H. Royster and Julia Doswell Royster

Standards and Regulations

Alice H. Suter

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Permissible exposure limits (PEL)for noise exposure, by nation

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

48. Radiation: Ionizing (6)

48. Radiation: Ionizing

Chapter Editor: Robert N. Cherry, Jr.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Robert N. Cherry, Jr.

Radiation Biology and Biological Effects

Arthur C. Upton

Sources of Ionizing Radiation

Robert N. Cherry, Jr.

Workplace Design for Radiation Safety

Gordon M. Lodde

Radiation Safety

Robert N. Cherry, Jr.

Planning for and Management of Radiation Accidents

Sydney W. Porter, Jr.

49. Radiation, Non-Ionizing (9)

49. Radiation, Non-Ionizing

Chapter Editor: Bengt Knave

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Electric and Magnetic Fields and Health Outcomes

Bengt Knave

The Electromagnetic Spectrum: Basic Physical Characteristics

Kjell Hansson Mild

Ultraviolet Radiation

David H. Sliney

Infrared Radiation

R. Matthes

Light and Infrared Radiation

David H. Sliney

Lasers

David H. Sliney

Radiofrequency Fields and Microwaves

Kjell Hansson Mild

VLF and ELF Electric and Magnetic Fields

Michael H. Repacholi

Static Electric and Magnetic Fields

Martino Grandolfo

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Sources and exposures for IR

2. Retinal thermal hazard function

3. Exposure limits for typical lasers

4. Applications of equipment using range >0 to 30 kHz

5. Occupational sources of exposure to magnetic fields

6. Effects of currents passing through the human body

7. Biological effects of various current density ranges

8. Occupational exposure limits-electric/magnetic fields

9. Studies on animals exposed to static electric fields

10. Major technologies and large static magnetic fields

11. ICNIRP recommendations for static magnetic fields

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

50. Vibration (4)

50. Vibration

Chapter Editor: Michael J. Griffin

Table of Contents

Table and Figures

Vibration

Michael J. Griffin

Whole-body Vibration

Helmut Seidel and Michael J. Griffin

Hand-transmitted Vibration

Massimo Bovenzi

Motion Sickness

Alan J. Benson

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Activities with adverse effects of whole-body vibration

2. Preventive measures for whole-body vibration

3. Hand-transmitted vibration exposures

4. Stages, Stockholm Workshop scale, hand-arm vibration syndrome

5. Raynaud’s phenomenon & hand-arm vibration syndrome

6. Threshold limit values for hand-transmitted vibration

7. European Union Council Directive: Hand-transmitted vibration (1994)

8. Vibration magnitudes for finger blanching

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

51. Violence (1)

51. Violence

Chapter Editor: Leon J. Warshaw

Table of Contents

Violence in the Workplace

Leon J. Warshaw

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Highest rates of occupational homicide, US workplaces, 1980-1989

2. Highest rates of occupational homicide US occupations, 1980-1989

3. Risk factors for workplace homicides

4. Guides for programmes to prevent workplace violence

52. Visual Display Units (11)

52. Visual Display Units

Chapter Editor: Diane Berthelette

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

Overview

Diane Berthelette

Characteristics of Visual Display Workstations

Ahmet Çakir

Ocular and Visual Problems

Paule Rey and Jean-Jacques Meyer

Reproductive Hazards - Experimental Data

Ulf Bergqvist

Reproductive Effects - Human Evidence

Claire Infante-Rivard

Case Study: A Summary of Studies of Reproductive Outcomes

Musculoskeletal Disorders

Gabriele Bammer

Skin Problems

Mats Berg and Sture Lidén

Psychosocial Aspects of VDU Work

Michael J. Smith and Pascale Carayon

Ergonomic Aspects of Human - Computer Interaction

Jean-Marc Robert

Ergonomics Standards

Tom F.M. Stewart

Tables

Click a link below to view table in article context.

1. Distribution of computers in various regions

2. Frequency & importance of elements of equipment

3. Prevalence of ocular symptoms

4. Teratological studies with rats or mice

5. Teratological studies with rats or mice

6. VDU use as a factor in adverse pregnancy outcomes

7. Analyses to study causes musculoskeletal problems

8. Factors thought to cause musculoskeletal problems

Figures

Point to a thumbnail to see figure caption, click to see figure in article context.

Working Under Increased Barometric Pressure

The atmosphere normally consists of 20.93% oxygen. The human body is naturally adapted to breathe atmospheric oxygen at a pressure of approximately 160 torr at sea level. At this pressure, haemoglobin, the molecule which carries oxygen to the tissue, is approximately 98% saturated. Higher pressures of oxygen cause little important increase in oxyhaemoglobin, since its concentration is virtually 100% to begin with. However, significant amounts of unburnt oxygen may pass into physical solution in the blood plasma as the pressure rises. Fortunately, the body can tolerate a fairly wide range of oxygen pressures without appreciable harm, at least in the short term. Longer term exposures may lead to oxygen toxicity problems.

When a job requires breathing compressed air, as in diving or caisson work, oxygen deficiency (hypoxia) is rarely a problem, as the body will be exposed to an increasing amount of oxygen as the absolute pressure rises. Doubling the pressure will double the number of molecules inhaled per breath while breathing compressed air. Thus the amount of oxygen breathed is effectively equal to 42%. In other words, a worker breathing air at a pressure of 2 atmospheres absolute (ATA), or 10 m beneath the sea, will breathe an amount of oxygen equal to breathing 42% oxygen by mask on the surface.

Oxygen toxicity

On the earth’s surface, human beings can safely continuously breathe 100% oxygen for between 24 and 36 hours. After that, pulmonary oxygen toxicity ensues (the Lorrain-Smith effect). The symptoms of lung toxicity consist of substernal chest pain; dry, non-productive cough; a drop in the vital capacity; loss of surfactant production. A condition known as patchy atelectasis is seen on x-ray examination, and with continued exposure microhaemorrhages and ultimately production of permanent fibrosis in the lung will develop. All stages of oxygen toxicity through the microhaemorrhage state are reversible, but once fibrosis sets in, the scarring process becomes irreversible. When 100% oxygen is breathed at 2 ATA, (a pressure of 10 m of sea water), the early symptoms of oxygen toxicity become manifest after about six hours. It should be noted that interspersing short, five-minute periods of air breathing every 20 to 25 minutes can double the length of time required for symptoms of oxygen toxicity to appear.

Oxygen can be breathed at pressures below 0.6 ATA without ill effect. For example, a worker can tolerate 0.6 atmosphere oxygen breathed continuously for two weeks without any loss of vital capacity. The measurement of vital capacity appears to be the most sensitive indicator of early oxygen toxicity. Divers working at great depths may breathe gas mixtures containing up to 0.6 atmospheres oxygen with the rest of the breathing medium consisting of helium and/or nitrogen. Six tenths of an atmosphere corresponds to breathing 60% oxygen at 1 ATA or at sea level.

At pressures greater than 2 ATA, pulmonary oxygen toxicity no longer becomes the primary concern, as oxygen can cause seizures secondary to cerebral oxygen toxicity. Neurotoxicity was first described by Paul Bert in 1878 and is known as the Paul Bert effect. If a person were to breathe 100% oxygen at a pressure of 3 ATA for much longer than three continuous hours, he or she will very likely suffer a grand mal seizure. Despite over 50 years of active research as to the mechanism of oxygen toxicity of the brain and lung, this response is still not completely understood. Certain factors are known, however, to enhance toxicity and to lower the seizure threshold. Exercise, CO2 retention, use of steroids, presence of fever, chilling, ingestion of amphetamines, hyperthyroidism and fear can have an oxygen tolerance effect. An experimental subject lying quietly in a dry chamber at pressure has much greater tolerance than a diver who is working actively in cold water underneath an enemy ship, for example. A military diver may experience cold, hard exercise, probable CO2 build-up using a closed-circuit oxygen rig, and fear, and may experience a seizure within 10-15 minutes working at a depth of only 12 m, whereas a patient lying quietly in a dry chamber may easily tolerate 90 minutes at a pressure of 20 m without great danger of seizure. Exercising divers may be exposed to partial pressure of oxygen up to 1.6 ATA for short periods up to 30 minutes, which corresponds to breathing 100% oxygen at a depth of 6 m. It is important to note that one should never expose anyone to 100% oxygen at a pressure greater than 3 ATA, nor for a time longer than 90 minutes at that pressure, even with a subject quietly recumbent.

There is considerable individual variation in susceptibility to seizure between individuals and, surprisingly, within the same individual, from day to day. For this reason, “oxygen tolerance” tests are essentially meaningless. Giving seizure-suppressing drugs, such as phenobarbital or phenytoin, will prevent oxygen seizures but do nothing to mitigate permanent brain or spinal cord damage if pressure or time limits are exceeded.

Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide can be a serious contaminant of the diver’s or caisson worker’s breathing air. The most common sources are internal combustion engines, used to power compressors, or other operating machinery in the vicinity of the compressors. Care should be taken to be sure that compressor air intakes are well clear of any sources of engine exhaust. Diesel engines usually produce little carbon monoxide but do produce large quantities of oxides of nitrogen, which can produce serious toxicity to the lung. In the United States, the current federal standard for carbon monoxide levels in inspired air is 35 parts per million (ppm) for an 8-hour working day. For example, at the surface even 50 ppm would not produce detectable harm, but at a depth of 50 m it would be compressed and produce the effect of 300 ppm. This concentration can produce a level of up to 40% carboxyhaemoglobin over a period of time. The actual analysed parts per million must be multiplied by the number of atmospheres at which it is delivered to the worker.

Divers and compressed-air workers should become aware of the early symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning, which include headache, nausea, dizziness and weakness. It is important to ensure that the compressor intake be always located upwind from the compressor engine exhaust pipe. This relationship must be continually checked as the wind changes or the vessels position shifts.

For many years it was widely assumed that carbon monoxide would combine with the body’s haemoglobin to produce carboxyhaemoglobin, causing its lethal effect by blocking transport of oxygen to the tissues. More recent work shows that although this effect does cause tissue hypoxia, it is not in itself fatal. The most serious damage occurs at the cellular level due to direct toxicity of the carbon monoxide molecule. Lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, which can only be terminated by hyperbaric oxygen treatment, appears to be the main cause of death and long-term sequelae.

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a normal product of metabolism and is eliminated from the lungs through the normal process of respiration. Various types of breathing apparatus, however, can impair its elimination or cause high levels to build up in the diver’s inspired air.

From a practical point of view, carbon dioxide can exert deleterious effects on the body in three ways. First, in very high concentrations (above 3%), it can cause judgmental errors, which at first may amount to inappropriate euphoria, followed by depression if the exposure is prolonged. This, of course, can have serious consequences for a diver under water who wants to maintain good judgement to remain safe. As the concentration climbs, CO2 will eventually produce unconsciousness when levels rise much above 8%. A second effect of carbon dioxide is to exacerbate or worsen nitrogen narcosis (see below). At partial pressures of above 40 mm Hg, carbon dioxide begins to have this effect (Bennett and Elliot 1993). At high PO2‘s, such as one is exposed to in diving, the respiratory drive due to high CO2 is attenuated and it is possible under certain conditions for divers who tend to retain CO2 to increase their levels of carbon dioxide sufficient to render them unconscious. The final problem with carbon dioxide under pressure is that, if the subject is breathing 100% oxygen at pressures greater than 2 ATA, the risk for seizures is greatly enhanced as carbon dioxide levels rise. Submarine crews have easily tolerated breathing 1.5% CO2 for two months at a time with no functional ill effect, a concentration that is thirty times the normal concentration found in atmospheric air. Five thousand ppm, or ten times the level found in normal fresh air, is considered safe for the purposes of industrial limits. However, even 0.5% CO2 added to 100% oxygen mix will predispose a person to seizures when breathed at increased pressure.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is an inert gas with regard to normal human metabolism. It does not enter into any form of chemical combination with compounds or chemicals within the body. However, it is responsible for severe impairment in a diver’s mental functioning when breathed under high pressure.

Nitrogen behaves as an aliphatic anaesthetic as atmospheric pressure increases, which results in the concentration of nitrogen also increasing. Nitrogen fits well into the Meyer-Overton hypothesis which states that any aliphatic anaesthetic will exhibit anaesthetic potency in direct proportion to its oil-water solubility ratio. Nitrogen, which is five times more soluble in fat than in water, produces an anaesthetic effect precisely at the predicted ratio.

In actual practice, diving to depths of 50 m can be accomplished with compressed-air, although the effects of nitrogen narcosis first become evident between 30 and 50 m. Most divers, however, can function adequately within these parameters. Deeper than 50 m, helium/oxygen mixtures are commonly used to avoid the effects of nitrogen narcosis. Air diving has been done to depths of slightly over 90 m, but at these extreme pressures, the divers were barely able to function and could hardly remember what tasks they had been sent down to accomplish. As noted earlier, any excess CO2 build-up further worsens the effect of nitrogen. Because ventilatory mechanics are affected by the density of gas at great pressures, there is an automatic CO2 build-up in the lung because of changes in laminar flow within the bronchioles and the diminution of the respiratory drive. Thus, air diving deeper than 50 m can be extremely dangerous.

Nitrogen exerts its effect by its simple physical presence dissolved in neural tissue. It causes a slight swelling of the neuronal cell membrane, which makes it more permeable to sodium and potassium ions. It is felt that interference with the normal depolarization/repolarization process is responsible for clinical symptoms of nitrogen narcosis.

Decompression

Decompression tables

A decompression table sets out the schedule, based on depth and time of exposure, for decompressing a person who has been exposed to hyperbaric conditions. Some general statements can be made about decompression procedures. No decompression table can be guaranteed to avoid decompression illness (DCI) for everyone, and indeed as described below, many problems have been noted with some tables currently in use. It must be remembered that bubbles are produced during every normal decompression, no matter how slow. For this reason, although it can be stated that the longer the decompression the less the likelihood of DCI, at the extreme of least likelihood, DCI becomes an essentially random event.

Habituation

Habituation, or acclimatization, occurs in divers and compressed-air workers, and renders them less susceptible to DCI after repeated exposures. Acclimatization can be produced after about a week of daily exposure, but it is lost after an absence from work of between 5 days to a week or by a sudden increase in pressure. Unfortunately construction companies have relied on acclimatization to make work possible with what are viewed as grossly inadequate decompression tables. To maximize the utility of acclimatization, new workers are often started at midshift to allow them to habituate without getting DCI. For example, the present Japanese Table 1 for compressed-air workers utilizes the split shift, with a morning and afternoon exposure to compressed air with a surface interval of one hour between exposures. Decompression from the first exposure is about 30% of that required by the US Navy and the decompression from the second exposure is only 4% of that required by the Navy. Nevertheless, habituation makes this departure from physiologic decompression possible. Workers with even ordinary susceptibility to decompression illness self-select themselves out of compressed-air work.

The mechanism of habituation or acclimatization is not understood. However, even if the worker is not experiencing pain, damage to brain, bone, or tissue may be taking place. Up to four times as many changes are visible on MRIs taken of the brains of compressed-air workers compared to age-matched controls that have been studied (Fueredi, Czarnecki and Kindwall 1991). These probably reflect lacunar infarcts.

Diving decompression

Most modern decompression schedules for divers and caisson workers are based on mathematical models akin to those developed originally by J.S. Haldane in 1908 when he made some empirical observations on permissible decompression parameters. Haldane observed that a pressure reduction of one half could be tolerated in goats without producing symptoms. Using this as a starting point, he then, for mathematical convenience, conceived of five different tissues in the body loading and unloading nitrogen at varying rates based on the classical half time equation. His staged decompression tables were then designed to avoid exceeding a 2:1 ratio in any of the tissues. Over the years, Haldane’s model has been modified empirically in attempts to make it fit what divers were observed to tolerate. However, all mathematical models for the loading and elimination of gases are flawed, since there are no decompression tables which remain as safe or become safer as time and depth are increased.

Probably the most reliable decompression tables currently available for air diving are those of the Canadian Navy, known as the DCIEM tables (Defence and Civil Institute of Environmental Medicine). These tables were tested thoroughly by non-habituated divers over a wide range of conditions and produce a very low rate of decompression illness. Other decompression schedules which have been well tested in the field are the French National Standards, originally developed by Comex, the French diving company.

The US Navy Air Decompression tables are unreliable, especially when pushed to their limits. In actual use, US Navy Master Divers routinely decompress for a depth 3 m (10 ft) deeper and/or one exposure time segment longer than required for the actual dive to avoid problems. The Exceptional Exposure Air Decompression Tables are particularly unreliable, having produced decompression illness on 17% to 33% of all the test dives. In general, the US Navy’s decompression stops are probably too shallow.

Tunnelling and caisson decompression

None of the air decompression tables which call for air breathing during decompression, currently in wide use, appear to be safe for tunnel workers. In the United States, the current federal decompression schedules (US Bureau of Labor Statuties 1971), enforced by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), have been shown to produce DCI in one or more workers on 42% of the working days while being used at pressures between 1.29 and 2.11 bar. At pressures over 2.45 bar, they have been shown to produce a 33% incidence of aseptic necrosis of the bone (dysbaric osteonecrosis). The British Blackpool Tables are also flawed. During the building of the Hong Kong subway, 83% of the workers using these tables complained of symptoms of DCI. They have also been shown to produce an incidence of dysbaric osteonecrosis of up to 8% at relatively modest pressures.

The new German oxygen decompression tables devised by Faesecke in 1992 have been used with good success in a tunnel under the Kiel Canal. The new French oxygen tables also appear to be excellent by inspection but have not yet been used on a large project.

Using a computer which examined 15 years of data from successful and unsuccessful commercial dives, Kindwall and Edel devised compressed-air caisson decompression tables for the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in 1983 (Kindwall, Edel and Melton 1983) using an empirical approach which avoided most of the pitfalls of mathematical modelling. Modelling was used only to interpolate between real data points. The research upon which these tables was based found that when air was breathed during decompression, the schedule in the tables did not produce DCI. However, the times used were prohibitively long and therefore impractical for the construction industry. When an oxygen variant of the table was computed, however, it was found that decompression time could be shortened to times similar to, or even shorter than, the current OSHA-enforced air decompression tables cited above. These new tables were subsequently tested by non-habituated subjects of varying ages at pressures ranging from 0.95 bar to 3.13 bar in 0.13 bar increments. Average work levels were simulated by weight lifting and treadmill walking during exposure. Exposure times were as long as possible, in keeping with the combined work time and decompression time fitting into an eight-hour work day. These are the only schedules which will be used in actual practice for shift work. No DCI was reported during these tests and bone scan and x ray failed to reveal any dysbaric osteonecrosis. To date, these are the only laboratory-tested decompression schedules in existence for compressed-air workers.

Decompression of hyperbaric chamber personnel

US Navy air decompression schedules were designed to produce a DCI incidence of less than 5%. This is satisfactory for operational diving, but much too high to be acceptable for hyperbaric workers who work in clinical settings. Decompression schedules for hyperbaric chamber attendants can be based on naval air decompression schedules, but since exposures are so frequent and thus are usually at the limits of the table, they must be liberally lengthened and oxygen should be substituted for compressed-air breathing during decompression. As a prudent measure, it is recommended that a two-minute stop be made while breathing oxygen, at least three metres deeper than called for by the decompression schedule chosen. For example, while the US Navy requires a three-minute decompression stop at three metres, breathing air, after a 101 minute exposure at 2.5 ATA, an acceptable decompression schedule for a hyperbaric chamber attendant undergoing the same exposure would be a two-minute stop at 6 m breathing oxygen, followed by ten minutes at 3 m breathing oxygen. When these schedules, modified as above, are used in practice, DCI in an inside attendant is an extreme rarity (Kindwall 1994a).

In addition to providing a fivefold larger “oxygen window” for nitrogen elimination, oxygen breathing offers other advantages. Raising the PO2 in venous blood has been demonstrated to lessen blood sludging, reduce the stickiness of white cells, reduce the no-reflow phenomenon, render red cells more flexible in passing through capillaries and counteract the vast decrease in deformability and filterability of white cells which have been exposed to compressed air.

Needless to say, all workers using oxygen decompression must be thoroughly trained and apprised of the fire danger. The environment of the decompression chamber must be kept free of combustibles and ignition sources, an overboard dump system must be used to convey exhaled oxygen out of the chamber and redundant oxygen monitors with a high oxygen alarm must be provided. The alarm should sound if oxygen in the chamber atmosphere exceeds 23%.

Working with compressed air or treating clinical patients under hyperbaric conditions sometimes can accomplish work or effect remission in disease that would otherwise be impossible. When rules for the safe use of these modalities are observed, workers need not be at significant risk for dysbaric injury.

Caisson Work and Tunnelling

From time to time in the construction industry it is necessary to excavate or tunnel through ground which is either fully saturated with water, lying below the local water table, or following a course completely under water, such as a river or lake bottom. A time-tested method for managing this situation has been to apply compressed air to the working area to force water out of the ground, drying it sufficiently so that it can be mined. This principle has been applied to both caissons used for bridge pier construction and soft ground tunnelling (Kindwall 1994b).

Caissons

A caisson is simply a large, inverted box, made to the dimensions of the bridge foundation, which typically is built in a dry dock and then floated into place, where it is carefully positioned. It is then flooded and lowered until it touches bottom, after which it is driven down further by adding weight as the bridge pier itself is constructed. The purpose of the caisson is to provide a method for cutting through soft ground to land the bridge pier on solid rock or a good geologic weight-bearing stratum. When all sides of the caisson have been embedded in the mud, compressed air is applied to the interior of the caisson and water is forced out, leaving a muck floor which can be excavated by men working within the caisson. The edges of the caisson consist of a wedge-shaped cutting shoe, made of steel, which continues to descend as earth is removed beneath the descending caisson and weight is applied from above as the bridge tower is constructed. When bed rock is reached, the working chamber is filled with concrete, becoming the permanent base for the bridge foundation.

Caissons have been used for nearly 150 years and have been successful in the construction of foundations as deep as 31.4 m below mean high water, as on Bridge Pier No. 3 of the Auckland, New Zealand, Harbour Bridge in 1958.

Design of the caisson usually provides for an access shaft for workers, who can descend either by ladder or by a mechanical lift and a separate shaft for buckets to remove the spoil. The shafts are provided with hermetically sealed hatches at either end which enable the caisson pressure to remain the same while workers or materials exit or enter. The top hatch of the muck shaft is provided with a pressure sealed gland through which the hoist cable for the muck bucket can slide. Before the top hatch is opened, the lower hatch is shut. Hatch interlocks may be necessary for safety, depending on design. Pressure must be equal on both sides of any hatch before it can be opened. Since the walls of the caisson are generally made of steel or concrete, there is little or no leakage from the chamber while under pressure except under the edges. The pressure is raised incrementally to a pressure just slightly greater than is necessary to balance off sea pressure at the edge of the cutting shoe.

People working in the pressurized caisson are exposed to compressed air and may experience many of the same physiologic problems that face deep-sea divers. These include decompression illness, barotrauma of the ears, sinus cavities and lungs and if decompression schedules are inadequate, the long-term risk of aseptic necrosis of the bone (dysbaric osteonecrosis).

It is important that a ventilation rate be established to carry away CO2 and gases emanating from the muck floor (especially methane) and whatever fumes may be produced from welding or cutting operations in the working chamber. A rule of thumb is that six cubic metres of free air per minute must be provided for each worker in the caisson. Allowance must also be made for air which is lost when the muck lock and man lock are used for the passage of personnel and materials. As the water is forced down to a level exactly even with the cutting shoe, ventilation air is required as the excess bubbles out under the edges. A second air supply, equal in capacity to the first, with an independent power source, should be available for emergency use in case of compressor or power failure. In many areas this is required by law.

Sometimes if the ground being mined is homogeneous and consists of sand, blow pipes can be erected to the surface. The pressure in the caisson will then extract the sand from the working chamber when the end of the blow pipe is located in a sump and the excavated sand is shovelled into the sump. If coarse gravel, rock, or boulders are encountered, these have to be broken up and removed in conventional muck buckets.

If the caisson should fail to sink despite the added weight on top, it may sometimes be necessary to withdraw the workers from the caisson and reduce the air pressure in the working chamber to allow the caisson to fall. Concrete must be placed or water admitted to the wells within the pier structure surrounding the air shafts above the caisson to reduce the stress on the diaphragm at the top of the working chamber. When just beginning a caisson operation, safety cribs or supports should be kept in the working chamber to prevent the caisson from suddenly dropping and crushing the workers. Practical considerations limit the depth to which air-filled caissons can be driven when men are used to hand mine the muck. A pressure of 3.4 kg/cm2 gauge (3.4 bar or 35 m of fresh water) is about the maximum tolerable limit because of decompression considerations for the workers.

An automated caisson excavating system has been developed by the Japanese wherein a remotely operated hydraulically powered backhoe shovel, which can reach all corners of the caisson, is used for excavation. The backhoe, under television control from the surface, drops the excavated muck into buckets which are hoisted remotely from the caisson. Using this system, the caisson can proceed down to almost unlimited pressures. The only time that workers need enter the working chamber is to repair the excavating machinery or to remove or demolish large obstacles which appear below the cutting shoe of the caisson and which cannot be removed by the remote-controlled backhoe. In such cases, workers enter for short periods much as divers and can breathe either air or mixed gas at higher pressures to avoid nitrogen narcosis.

When people have worked long shifts under compressed-air at pressures greater than 0.8 kg/cm2 (0.8 bar), they must decompress in stages. This can be accomplished either by attaching a large decompression chamber to the top of the man shaft into the caisson or, if space requirements are such at the top that this is impossible, by attaching “blister locks” to the man shaft. These are small chambers which can accommodate only a few workers at a time in a standing position. Preliminary decompression is taken in these blister locks, where the time spent is relatively short. Then, with considerable excess gas remaining in their bodies, the workers rapidly decompress to the surface and quickly move to a standard decompression chamber, sometimes located on an adjacent barge, where they are repressurized for subsequent slow decompression. In compressed-air work, this process is known as “decanting” and was fairly common in England and elsewhere, but is prohibited in the United States. The object is to return workers to pressure within five minutes, before bubbles can grow sufficiently in size to cause symptoms. However, this is inherently dangerous because of the difficulties of moving a large gang of workers from one chamber to another. If one worker has trouble clearing his ears during repressurization, the whole shift is placed in jeopardy. There is a much safer procedure, called “surface decompression”, for divers, where only one or two are decompressed at the same time. Despite every precaution on the Auckland Harbour Bridge project, as many as eight minutes occasionally elapsed before bridge workers could be put back under pressure.

Compressed air tunnelling

Tunnels are becoming increasingly important as the population grows, both for the purposes of sewage disposal and for unobstructed traffic arteries and rail service beneath large urban centres. Often, these tunnels must be driven through soft ground considerably below the local water table. Under rivers and lakes, there may be no other way to ensure the safety of the workers than to put compressed air on the tunnel. This technique, using a hydraulically driven shield at the face with compressed air to hold back the water, is known as the plenum process. Under large buildings in a crowded city, compressed air may be necessary to prevent surface subsidence. When this occurs, large buildings can develop cracks in their foundations, sidewalks and streets may drop and pipes and other utilities can be damaged.

To apply pressure to a tunnel, bulkheads are erected across the tunnel to provide the pressure boundary. On smaller tunnels, less than three metres in diameter, a single or combination lock is used to provide access for workers and materials and removal of the excavated ground. Removable track sections are provided by the doors so that they may be operated without interference from the muck-train rails. Numerous penetrations are provided in these bulkheads for the passage of high-pressure air for the tools, low-pressure air for pressurizing the tunnel, fire mains, pressure gauge lines, communications lines, electrical power lines for lighting and machinery and suction lines for ventilation and removal of water in the invert. These are often termed blow lines or “mop lines”. The low-pressure air supply pipe, which is 15-35 cm in diameter, depending on the size of the tunnel, should extend to the working face in order to ensure good ventilation for the workers. A second low-pressure air pipe of equal size should also extend through both bulkheads, terminating just inside the inner bulkhead, to provide air in the event of rupture or break in the primary air supply. These pipes should be fitted with flapper valves which will close automatically to prevent depressurization of the tunnel if the supply pipe is broken. The volume of air required to efficiently ventilate the tunnel and keep CO2 levels low will vary greatly depending on the porosity of the ground and how close the finished concrete lining has been brought to the shield. Sometimes micro-organisms in the soil produce large amounts of CO2. Obviously, under such conditions, more air will be required. Another useful property of compressed air is that it tends to force explosive gases such as methane away from the walls and out of the tunnel. This holds true when mining areas where spilled solvents such as petrol or degreasers have saturated the ground.

A rule of thumb developed by Richardson and Mayo (1960) is that the volume of air required usually can be calculated by multiplying the area of the working face in square metres by six and adding six cubic metres per man. This gives the number of cubic metres of free air required per minute. If this figure is used, it will cover most practical contingencies.

The fire main must also extend through to the face and be provided with hose connections every sixty metres for use in case of fire. Thirty metres of rotproof hose should be attached to the water-filled fire main outlets.

In very large tunnels, over about four metres in diameter, two locks should be provided, one termed the muck lock, for passing muck trains, and the man lock, usually positioned above the muck lock, for the workers. On large projects, the man lock is often made of three compartments so that engineers, electricians and others can lock in and out past a work shift undergoing decompression. These large man locks are usually built external to the main concrete bulkhead so they do not have to resist the external compressive force of the tunnel pressure when open to the outside air.

On very large subaqueous tunnels a safety screen is erected, spanning the upper half of the tunnel, to afford some protection should the tunnel suddenly flood secondary to a blow-out while tunnelling under a river or lake. The safety screen is usually placed as close as practicable to the face, avoiding the excavating machinery. A flying gangway or hanging walkway is used between the screen and the locks, the gangway dropping down to pass at least a metre below the lower edge of the screen. This will allow the workers egress to the man lock in the event of sudden flooding. The safety screen can also be used to trap light gases which may be explosive and a mop line can be attached through the screen and coupled to a suction or blow line. With the valve cracked, this will help to purge any light gases from the working environment. Because the safety screen extends nearly down to the centre of the tunnel, the smallest tunnel it can be employed on is about 3.6 m. It should be noted that workers must be warned to keep clear of the open end of the mop line, as serious accidents can be caused if clothing is sucked into the pipe.

Table 1 is a list of instructions which should be given to compressed-air workers before they first enter the compressed-air environment.

It is the responsibility of the retained physician or occupational health professional for the tunnel project to ensure that air purity standards are maintained and that all safety measures are in effect. Adherence to established decompression schedules by periodically examining the pressure recording graphs from the tunnel and man locks must also be carefully monitored.

Table 1. Instructions for compressed-air workers

- Never “short” yourself on the decompression times prescribed by your employer and the official decompression code in use. The time saved is not worth the risk of decompression illness (DCI), a potentially fatal or crippling disease.

- Do not sit in a cramped position during decompression. To do so allows nitrogen bubbles to gather and concentrate in the joints, thereby contributing to the risk of DCI. Because you are still eliminating nitrogen from your body after you go home, you should refrain from sleeping or resting in a cramped position after work, as well.

- Warm water should be used for showers and baths up to six hours after decompressing; very hot water can actually bring on or aggravate a case of decompression illness.

- Severe fatigue, lack of sleep and heavy drinking the night before can also help bring on decompression illness. Drinking alcohol and taking aspirin should never be used as a “treatment” for pains of decompression illness.

- Fever and illness, such as bad colds, increase the risk of decompression illness. Strains and sprains in muscles and joints are also “favourite” places for DCI to begin.

- When stricken by decompression illness away from the job site, immediately contact the company’s physician or one knowledgeable in treating this disease. Wear your identifying bracelet or badge at all times.

- Leave smoking materials in the changing shack. Hydraulic oil is flammable and should a fire start in the closed environment of the tunnel, it could cause extensive damage and a shutdown of the job, which would lay you off work. Also, because the air is thicker in the tunnel due to compression, heat is conducted down cigarettes so that they become too hot to hold as they get shorter.

- Do not bring thermos bottles in your lunch box unless you loosen the stopper during compression; if you do not do this, the stopper will be forced deep into the thermos bottle. During decompression, the stopper must also be loosened so that the bottle does not explode. Very fragile glass thermos bottles might implode when pressure is applied, even if the stopper is loose.

- When the air lock door has been closed and pressure is applied, you will notice that the air in the air lock gets warm. This is called the “heat of compression” and is normal. Once the pressure stops changing, the heat will dissipate and the temperature will return to normal. During compression, the first thing you will notice is a fullness of your ears. Unless you “clear your ears” by swallowing, yawning, or holding your nose and trying to “blow the air out through your ears”, you will experience ear pain during compression. If you cannot clear your ears, notify the shift foreman immediately so that compression can be halted. Otherwise you may break your eardrums or develop a severe ear squeeze. Once you have reached maximum pressure, there will be no further problems with your ears for the remainder of the shift.

- Should you experience buzzing in your ears, ringing in your ears, or deafness following compression which persists for more than a few hours, you must report to the compressed-air physician for evaluation. Under extremely severe but rare conditions, a portion of the middle ear structure other than the eardrum may be affected if you have had a great deal of difficulty clearing your ears and in that case this must be surgically corrected within two or three days to avoid permanent difficulty.

- If you have a cold or an attack of hay fever, it is best not to try compressing in the air lock until you are over it. Colds tend to make it difficult or impossible for you to equalize your ears or sinuses.

Hyperbaric chamber workers

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is becoming more common in all areas of the world, with some 2,100 hyperbaric chamber facilities now functioning. Many of these chambers are multiplace units, which are compressed with compressed air to pressures ranging from 1 to 5 kg/cm2 gauge. Patients are given 100% oxygen to breathe, at pressures up to 2 kg/cm2 gauge. At pressures greater than that they may breathe mixed gas for treatment of decompression illness. The chamber attendants, however, typically breathe compressed air and so their exposure in the chamber is similar to that experienced by a diver or compressed-air worker.

Typically the chamber attendant working inside a multiplace chamber is a nurse, respiratory therapist, former diver, or hyperbaric technician. The physical requirements for such workers are similar to those for caisson workers. It is important to remember, however, that a number of chamber attendants working in the hyperbaric field are female. Women are no more likely to suffer ill effects from compressed-air work than men, with the exception of the question of pregnancy. Nitrogen is carried across the placenta when a pregnant woman is exposed to compressed air and this is transferred to the foetus. Whenever decompression takes place, nitrogen bubbles form in the venous system. These are silent bubbles and, when small, do no harm, as they are removed efficiently by the pulmonary filter. The wisdom, however, of having these bubbles appear in a developing foetus is doubtful. What studies have been done indicate that foetal damage may occur under such circumstances. One survey suggested that birth defects are more common in the children of women who have engaged in scuba diving while pregnant. Exposure of pregnant women to hyperbaric chamber conditions should be avoided and appropriate policies consistent with both medical and legal considerations must be developed. For this reason, female workers should be precautioned about the risks during pregnancy and appropriate personnel job assignment and health education programmes should be instituted in order that pregnant women not be exposed to hyperbaric chamber conditions.

It should be pointed out, however, that patients who are pregnant may be treated in the hyperbaric chamber, as they breathe 100% oxygen and are therefore not subject to nitrogen embolization. Previous concerns that the foetus would be at increased risk for retrolental fibroplasia or retinopathy of the newborn have proven to be unfounded in large clinical trials. Another condition, premature closure of the patent ductus arteriosus, has also not been found to be related to the exposure.

Other Hazards

Physical injuries

Divers

In general, divers are prone to the same types of physical injury that any worker is liable to sustain when working in heavy construction. Breaking cables, failing loads, crush injuries from machines, turning cranes and so on, can be commonplace. However, in the underwater environment, the diver is prone to certain types of unique injury that are not found elsewhere.

Suction/entrapment injury is something especially to be guarded against. Working in or near an opening in a ship’s hull, a caisson which has a lower water level on the side opposite the diver, or a dam can be causative of this type of mishap. Divers often refer to this type of situation as being trapped by “heavy water”.

To avoid dangerous situations where the diver’s arm, leg, or whole body may be sucked into an opening such as a tunnel or pipe, strict precautions must be taken to tag out pipe valves and flood gates on dams so that they cannot be opened while the diver is in the water near them. The same is true of pumps and piping within ships that the diver is working on.

Injury can include oedema and hypoxia of an entrapped limb sufficient to cause muscle necrosis, permanent nerve damage, or even loss of the entire limb, or it may occasion gross crushing of a portion of the body or the whole body so as to cause death from simple massive trauma. Entrapment in cold water for a long period of time may cause the diver to die of exposure. If the diver is using scuba gear, he may run out of air and drown before his release can be effected, unless additional scuba tanks can be provided.

Propeller injuries are straightforward and must be guarded against by tagging out a ship’s main propulsion machinery while the diver is in the water. It must be remembered, however, that steam turbine-powered ships, when in port, are continuously turning over their screws very slowly, using their jacking gear to avoid cooling and distortion of the turbine blades. Thus the diver, when working on such a blade (trying to clear it from entangled cables, for example), must be aware that the turning blade must be avoided as it approaches a narrow spot close to the hull.

Whole-body squeeze is a unique injury which can occur to deep sea divers using the classical copper helmet mated to the flexible rubberized suit. If there is no check valve or non-return valve where the air pipe connects to the helmet, cutting the air line at the surface will cause an immediate relative vacuum within the helmet, which can draw the entire body into the helmet. The effects of this can be instant and devastating. For example, at a depth of 10 m, about 12 tons of force is exerted on the soft part of the diver’s dress. This force will drive his body into the helmet if pressurization of the helmet is lost. A similar effect may be produced if the diver fails unexpectedly and fails to turn on compensating air. This can produce severe injury or death if it occurs near the surface, as a 10-metre fall from the surface will halve the volume of the dress. A similar fall occurring between 40 and 50 m will change the suit volume only about 17%. These volume changes are in accordance with Boyle’s Law.

Caisson and tunnel workers

Tunnel workers are subject to the usual types of accidents seen in heavy construction, with the additional problem of a higher incidence of falls and injuries from cave-ins. It must be stressed that an injured compressed-air worker who may have broken ribs should be suspected of having a pneumothorax until proven otherwise and therefore great care must be taken in decompressing such a patient. If a pneumothorax is present, it must be relieved at pressure in the working chamber before decompression is attempted.

Noise

Noise damage to compressed-air workers may be severe, as air motors, pneumatic hammers and drills are never properly equipped with silencers. Noise levels in caissons and tunnels have been measured at over 125 dB. These levels are physically painful, as well as causative of permanent damage to the inner ear. Echo within the confines of a tunnel or caisson exacerbates the problem.

Many compressed-air workers balk at wearing ear protection, saying that blocking the sound of an approaching muck train would be dangerous. There is little foundation for this belief, as hearing protection at best only attenuates sound but does not eliminate it. Furthermore, not only is a moving muck train not “silent” to a protected worker, but it also gives other cues such as moving shadows and vibration in the ground. A real concern is complete hermetic occlusion of the auditory meatus provided by a tightly fitting ear muff or protector. If air is not admitted to the external auditory canal during compression, external ear squeeze may result as the ear drum is forced outward by air entering the middle ear via the Eustachian tube. The usual sound protective ear muff is usually not completely air tight, however. During compression, which lasts only a tiny fraction of the total shift time, the muff can be slightly loosened should pressure equalization prove a problem. Formed fibre ear plugs which can be moulded to fit in the external canal provide some protection and are not air tight.

The goal is to avoid a time weighted average noise level of higher than 85 dBA. All compressed-air workers should have pre-employment base line audiograms so that auditory losses which may result from the high-noise environment can be monitored.

Hyperbaric chambers and decompression locks can be equipped with efficient silencers on the air supply pipe entering the chamber. It is important that this be insisted on, as otherwise the workers will be considerably bothered by the ventilation noise and may neglect to ventilate the chamber adequately. A continuous vent can be maintained with a silenced air supply producing no more than 75dB, about the noise level in an average office.

Fire

Fire is always of great concern in compressed-air tunnel work and in clinical hyperbaric chamber operations. One can be lulled into a false sense of security when working in a steel-walled caisson which has a steel roof and a floor consisting only of unburnable wet muck. However, even in these circumstances, an electrical fire can burn insulation, which will prove highly toxic and can kill or incapacitate a work crew very quickly. In tunnels which are driven using wooden lagging before the concrete is poured, the danger is even greater. In some tunnels, hydraulic oil and straw used for caulking can furnish additional fuel.

Fire under hyperbaric conditions is always more intense because there is more oxygen available to support combustion. A rise from 21% to 28% in the oxygen percentage will double the burning rate. As the pressure is increased, the amount of oxygen available to burn increases The increase is equal to the percentage of oxygen available multiplied by the number of atmospheres in absolute terms. For example, at a pressure of 4 ATA (equal to 30 m of sea water), the effective oxygen percentage would be 84% in compressed-air. However, it must be remembered that even though burning is very much accelerated under such conditions, it is not the same as the speed of burning in 84% oxygen at one atmosphere. The reason for this is that the nitrogen present in the atmosphere has a certain quenching effect. Acetylene cannot be used at pressures over one bar because of its explosive properties. However, other torch gases and oxygen can be used for cutting steel. This has been done safely at pressures up to 3 bar. Under such circumstances, however, scrupulous care must be exercised and someone must stand by with a fire hose to immediately quench any fire which might start, should an errant spark come in contact with something combustible.

Fire requires three components to be present: fuel, oxygen and an ignition source. If any one of these three factors is absent, fire will not occur. Under hyperbaric conditions, it is almost impossible to remove oxygen unless the piece of equipment in question can be inserted into the environment by filling it or surrounding it with nitrogen. If fuel cannot be removed, an ignition source must be avoided. In clinical hyperbaric work, meticulous care is taken to prevent the oxygen percentage in the multiplace chamber from rising above 23%. In addition, all electrical equipment within the chamber must be intrinsically safe, with no possibility of producing an arc. Personnel in the chamber should wear cotton clothing which has been treated with flame retardant. A water-deluge system must be in place, as well as a hand-held fire hose independently actuated. If a fire occurs in a multiplace clinical hyperbaric chamber, there is no immediate escape and so the fire must be fought with a hand-held hose and with the deluge system.

In monoplace chambers pressurized with 100% oxygen, a fire will be instantly fatal to any occupant. The human body itself supports combustion in 100% oxygen, especially at pressure. For this reason, plain cotton clothing is worn by the patient in the monoplace chamber to avoid static sparks which could be produced by synthetic materials. There is no need to fireproof this clothing, however, as if a fire should occur, the clothing would afford no protection. The only method for avoiding fires in the monoplace oxygen-filled chamber is to completely avoid any source of ignition.

When dealing with high pressure oxygen, at pressures over 10 kg/cm2 gauge, adiabatic heating must be recognized as a possible source of ignition. If oxygen at a pressure of 150 kg/cm2 is suddenly admitted to a manifold via a quick-opening ball valve, the oxygen may “diesel” if even a tiny amount of dirt is present. This can produce a violent explosion. Such accidents have occurred and for this reason, quick-opening ball valves should never be used in high pressure oxygen systems.

Decompression Disorders

A wide range of workers are subject to decompression (a reduction in ambient pressure) as part of their working routine. These include divers who themselves are drawn from a wide range of occupations, caisson workers, tunnellers, hyperbaric chamber workers (usually nurses), aviators and astronauts. Decompression of these individuals can and does precipitate a variety of decompression disorders. While most of the disorders are well understood, others are not and in some instances, and despite treatment, injured workers can become disabled. The decompression disorders are the subject of active research.

Mechanism of Decompression Injury

Principles of gas uptake and release

Decompression may injure the hyperbaric worker via one of two primary mechanisms. The first is the consequence of inert gas uptake during the hyperbaric exposure and bubble formation in tissues during and after the subsequent decompression. It is generally assumed that the metabolic gases, oxygen and carbon dioxide, do not contribute to bubble formation. This is almost certainly a false assumption, but the consequent error is small and such an assumption will be made here.

During the compression (increase in ambient pressure) of the worker and throughout their time under pressure, inspired and arterial inert gas tensions will be increased relative to those experienced at normal atmospheric pressure—the inert gas(es) will then be taken up into tissues until an equilibrium of inspired, arterial and tissue inert gas tensions is established. Equilibrium times will vary from less than 30 minutes to more than a day depending upon the type of tissue and gas involved, and, in particular, will vary according to:

- the blood supply to the tissue

- the solubility of the inert gas in blood and in the tissue

- the diffusion of the inert gas through blood and into the tissue

- the temperature of the tissue

- the local tissue work-loads

- the local tissue carbon dioxide tension.

The subsequent decompression of the hyperbaric worker to normal atmospheric pressure will clearly reverse this process, gas will be released from tissues and will eventually be expired. The rate of this release is determined by the factors listed above, except, for as yet poorly understood reasons, it appears to be slower than the uptake. Gas elimination will be slower still if bubbles form. The factors that influence the formation of bubbles are well established qualitatively, but not quantitatively. For a bubble to form the bubble energy must be sufficient to overcome ambient pressure, surface tension pressure and elastic tissue pressures. The disparity between theoretical predictions (of surface tension and critical bubble volumes for bubble growth) and actual observation of bubble formation is explained variously by arguing that bubbles form in tissue (blood vessel) surface defects and/or on the basis of small short-lived bubbles (nuclei) that are continually formed in the body (e.g., between tissue planes or in areas of cavitation). The conditions that must exist before gas comes out of solution are also poorly defined—although it is likely that bubbles form whenever tissue gas tensions exceed ambient pressure. Once formed, bubbles provoke injury (see below) and become increasingly stable as a consequence of coalescence and recruitment of surfactants to the bubble surface. It may be possible for bubbles to form without decompression by changing the inert gas that the hyperbaric worker is breathing. This effect is probably small and those workers that have had a sudden onset of a decompression illness after a change in inspired inert gas almost certainly already had “stable” bubbles in their tissues.

It follows that to introduce a safe working practice a decompression programme (schedule) should be employed to avoid bubble formation. This will require modelling of the following:

- the uptake of the inert gas(es) during the compression and the hyperbaric exposure

- the elimination of the inert gas(es) during and after the decompression

- the conditions for bubble formation.

It is reasonable to state that to date no completely satisfactory model of decompression kinetics and dynamics has been produced and that hyperbaric workers now rely on programmes that have been established essentially by trial and error.

Effect of Boyle’s Law on barotrauma

The second primary mechanism by which decompression can cause injury is the process of barotrauma. The barotraumata can arise from compression or decompression. In compression barotrauma, the air spaces in the body that are surrounded by soft tissue, and hence are subject to increasing ambient pressure (Pascal’s principle), will be reduced in volume (as reasonably predicted by Boyles’ law: doubling of ambient pressure will cause gas volumes to be halved). The compressed gas is displaced by fluid in a predictable sequence:

- The elastic tissues move (tympanic membrane, round and oval windows, mask material, clothing, rib cage, diaphragm).

- Blood is pooled in the high compliance vessels (essentially veins).

- Once the limits of compliance of blood vessels are reached, there is an extravasation of fluid (oedema) and then blood (haemorrhage) into the surrounding soft tissues.

- Once the limits of compliance of the surrounding soft tissues are reached, there is a shift of fluid and then blood into the air space itself.

This sequence can be interrupted at any time by an ingress of additional gas into the space (e.g., into the middle ear on performing a valsalva manoeuvre) and will stop when gas volume and tissue pressure are in equilibrium.

The process is reversed during decompression and gas volumes will increase, and if not vented to atmosphere will cause local trauma. In the lung this trauma may arise from either over-distension or from shearing between adjacent areas of lung that have significantly different compliance and hence expand at different rates.

Pathogenesis of Decompression Disorders

The decompression illnesses can be divided into the barotraumata, tissue bubble and intravascular bubble categories.

Barotraumata

During compression, any gas space may become involved in barotrauma and this is especially common in the ears. While damage to the external ear requires occlusion of the external ear canal (by plugs, a hood, or impacted wax), the tympanic membrane and middle ear is frequently damaged. This injury is more likely if the worker has upper respiratory tract pathology that causes eustachian tube dysfunction. The possible consequences are middle ear congestion (as described above) and/or tympanic membrane rupture. Ear pain and a conductive deafness are likely. Vertigo may result from an ingress of cold water into the middle ear through a ruptured tympanic membrane. Such vertigo is transient. More commonly, vertigo (and possibly also a sensorineural deafness) will result from inner ear barotrauma. During compression, inner ear damage often results from a forceful valsalva manoeuvre (that will cause a fluid wave to be transmitted to the inner ear via the cochlea duct). The inner ear damage is usually within the inner ear—round and oval window rupture is less common.

The paranasal sinuses often are similarly involved and usually because of a blocked ostium. In addition to local and referred pain, epistaxis is common and cranial nerves may be “compressed”. It is noteworthy that the facial nerve may be likewise affected by middle ear barotrauma in individuals with a perforate auditory nerve canal. Other areas that may be affected by compressive barotrauma, but less commonly, are the lungs, teeth, gut, diving mask, dry-suits and other equipment such as buoyancy compensating devices.